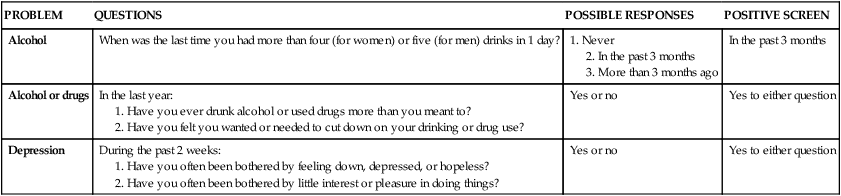

1. Describe community-based psychiatric treatment settings. 2. Compare and contrast models of community-based psychiatric care and the role of the nurse. 3. Assess the needs of vulnerable psychiatric populations living in the community. Most people seek help for their mental health problems from their primary care provider. Primary care settings may be the most important point of contact between patients with psychiatric problems and the health care system. The role of the primary care provider is even more important for older adults and patients from racial and ethnic minorities (Lyness et al, 2009). The three most common problems seen in primary care are depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Many patients with mental health problems are not treated effectively in the primary care setting. About 50% of mental health problems are not identified or treated in primary care, and about two thirds of primary care providers reported that they could not get outpatient mental health services for their patients (Cunningham, 2009; Ong and Rubenstein, 2009; Machado and Tomlinson, 2011). Federally funded community health centers have increased their specialty mental health offerings, but this is not sufficient to meet the need (Wells et al, 2010). The other side of the problem is equally compelling. People with serious mental illness have more difficulty in obtaining a primary care provider and experience greater barriers to medical care than the general population. The result is that they die 25 years earlier than the general population (Bradford et al, 2008; Green et al, 2010). These system problems have given rise to discussions about the integration of behavioral health care in the primary care setting, and general medical care in the behavioral health care setting. The goal of integrated services is improved health outcomes and decreased costs. Nurses could play a prominent role in an integrated primary care setting (Weiss et al, 2009). Truly integrated care needs to be a two-way street that includes the following: • People in primary care settings who have behavioral health problems are identified and treated in primary care settings if possible. • People in behavioral health care settings who need routine primary care are identified and treated in the behavioral health setting if possible. Behavioral health service delivery in the primary care setting can reach many people who otherwise would not receive behavioral health intervention. It also provides a level of expertise regarding diagnosis and intervention for problems not generally seen in the medical setting, resulting in increased knowledge and skill in detection and treatment of behavioral health problems within the medical community. Primary care services for those who are mentally ill also can result in better quality of care for these patients (Canters for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Kilbourne et al, 2011). An important step in addressing this issue is the use of effective screening measures in primary care (Neushotz and Fitzpatrick, 2008; Oleski et al, 2010). The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2010) recommends the following: • Screening adults for depression in clinical practices that have systems in place to ensure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up • Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce alcohol misuse by adults, including pregnant women in primary care settings Research has shown that one- or two-item screening tools are effective in identifying those at risk for substance use or depressive disorders (Table 34-1). Because these questions can be answered in seconds, they can be asked during routine visits. A variety of screening tools can be used in primary care (Gilbody et al, 2007; Bernstein et al, 2009; Gaynes et al, 2010; Katzelnick et al, 2011). Nurses should incorporate these screening tools in their practice. TABLE 34-1 A framework that nurses can use for behavioral counseling in primary care is the Five A’s: • Assess: Ask about a person’s behavioral health risk and factors affecting his or her choice of future goals. • Advise: Give clear, specific, and personalized behavioral change advice, including information about personal health harms and benefits. • Agree: Collaboratively select appropriate treatment goals based on the patient’s interest in and willingness to change the behavior. • Assist: Help the person achieve agreed-on goals by acquiring the skills, confidence, and support for change. • Arrange: Schedule follow-up contacts (in person or by telephone) to provide ongoing support, including referral to a specialist if needed. Providing safe and effective care for psychiatric patients in EDs can be challenging. Overcrowding, noise levels, and chaotic conditions may trigger a worsening of the patient’s condition. Another safety concern is access to dangerous items. A study conducted by the Emergency Nurses Association (ENA) found that only 19% of EDs had space dedicated to mental health care (Howard, 2006). Patients also present to the ED for medical clearance before psychiatric admission. There are no standard protocols for medical clearance, and demands for this service can be the source of conflict between emergency and psychiatric providers (Reeves et al, 2010). The gaps between psychiatric and emergency care in the current health care system create serious problems for patients and staff alike. Boarding is the practice of maintaining patients in the ED while waiting for psychiatric services to be available. Significant psychiatric bed shortages, increasing demand for psychiatric services, and lack of adequate funding for psychiatric services create the need for this unfortunate practice. Boarding frequently lasts more than 24 hours and sometimes days. It may result in safety and quality issues for all ED patients and can have a negative impact on staff workload and morale. Providing psychiatric consultants, having a separated area within the ED, and creating a separate psychiatric ED are suggested improvement strategies (Bender et al, 2008; Alakeson et al, 2010). Some acute care hospitals have dedicated psychiatric services available in the ED. These services have evolved from crisis intervention to diagnostic and treatment services, often with on-site treatment and referral to community services. However, nurses and other clinicians working in EDs tend to focus less on behavioral health problems than on physical illnesses and injuries. The reasons for this include time constraints, lack of knowledge about how to screen and intervene effectively, reimbursement issues, and bias and stigma about psychiatric care (Nadler-Moodie, 2010). Psychiatric home care programs receive and refer patients from the entire community’s general medical and mental health care services (Box 34-1). Psychiatric home care ranges from serving as an alternative to hospitalization, to functioning as a single home visit for the purposes of evaluating a specific issue, to providing treatment in the home. The advantages of psychiatric home care is that it can provide the following: • A way to provide care that removes the need for patient travel • A way to assess and treat in the patient’s own living setting • An alternative to hospitalization by maintaining a patient in the community • A facilitator of an impending hospital admission through preadmission assessment • An enhancement of inpatient treatment through integration of home issues in the inpatient treatment plan • A way to shorten inpatient stays while keeping the patient engaged in active treatment • A part of the discharge planning process by assessing potential problems and issues Examples of other advantages include its outreach capacity and emphasis on patient participation, responsibility, autonomy, and satisfaction. An excellent example of psychiatric home care is the Nurse Home-Visiting Program for mothers with depression (Box 34-2). In determining psychiatric homebound status, a useful definition is a patient who is unable to independently and consistently access psychiatric follow-up. This definition is broad enough to include a person who is physically healthy and mobile but too depressed to get out of bed. It also includes patients with agoraphobia and patients with psychotic thinking processes who are vulnerable in the community. Box 34-3 lists some conditions that may make a patient psychiatrically homebound. Psychiatric home care is a subspecialty that calls for a nurse with certain kinds of skills, education, and experience. Box 34-4 outlines Medicare requirements for psychiatric nurses practicing in the home setting. E-therapy is the use of electronic media and information technologies to provide services for participants in different locations. E-therapy can be used to provide education, assessment, diagnosis, treatment engagement, direct treatment, and aftercare services. Providers can give and receive training and supervision using electronic forms of communication (Cleary et al, 2008; Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2009). This includes graduate programs in psychiatric nursing (Delaney et al, 2011). In terms of access to services, online counseling may benefit people who are isolated in rural areas and underserved. Treatment providers can make themselves more available to those in need compared with providers administering face-to-face treatment. For example, e-therapy services can be found in rural clinics, military programs, correctional facilities, community mental health centers, nursing homes, home health care settings, and hospitals (Dwight-Johnson et al, 2011). E-therapy can be one solution to the shortage of mental health providers for children and adolescents (Ellington and McGuinness, 2011). Text messaging, which is popular among youth, can provide other opportunities (Box 34-5). • Text-based forms of communication include e-mail, chat rooms, text messaging, and listservs. • Non–text-based forms include telephone and videoconferencing. Telepsychiatry connects people by audiovisual communication and is one means of providing expert health care services to patients distant from a source of care. It is suggested for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in remote locations or where psychiatric expertise is scarce. Research suggests that psychiatric consultation and short-term follow-up can be as effective when delivered by telepsychiatry as when provided face to face (García-Lizana and Muñoz-Mayorga, 2010). When used with established ethical guidelines, computers offer a reliable, inexpensive, accessible, and time-efficient way of assessing psychiatric symptoms, implementing treatment guidelines, and providing care (Borzekowski et al, 2009). Computer-administered versions of clinician-administered rating scales are available for the assessment of a number of psychiatric illnesses, including depression, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and social phobia. Patient reaction has been positive, with patients usually being more honest with their responses and often expressing a preference for the computer-administered assessments of sensitive areas such as suicide, alcohol and drug use, sexual behavior, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–related symptoms (Lieberman and Huang, 2008; Wolford et al, 2008).

Community-Based Psychiatric Nursing Care

Treatment Settings

Primary Care Settings

PROBLEM

QUESTIONS

POSSIBLE RESPONSES

POSITIVE SCREEN

Alcohol

When was the last time you had more than four (for women) or five (for men) drinks in 1 day?

1. Never

2. In the past 3 months

3. More than 3 months ago

In the past 3 months

Alcohol or drugs

In the last year:

1. Have you ever drunk alcohol or used drugs more than you meant to?

2. Have you felt you wanted or needed to cut down on your drinking or drug use?

Yes or no

Yes to either question

Depression

During the past 2 weeks:

1. Have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?

2. Have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?

Yes or no

Yes to either question

Emergency Department Psychiatric Care

Home Psychiatric Care

Virtual Mental Health Care

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Community-Based Psychiatric Nursing Care

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access