Community Assessment

Frances A. Maurer and Claudia M. Smith

Focus Questions

What is community-focused nursing?

What are the critical components of a community?

How are groups and aggregates considered different types of populations?

What are different types of community boundaries?

What are the goals of communities?

What are the frameworks for assessing communities?

What is a general systems framework for assessing communities?

What are the factors to consider in assessing the health of communities?

What are the sources of data regarding communities?

What are the approaches to community assessment?

How do community/public health nurses analyze community data?

Key Terms

Aggregate

Asset

Census tract

Community

Community capacity

Community competence

Community resiliency

Geopolitical

Group

Healthy community

Phenomenological

Population

Population “at risk”

Target population

The community/public health nurse is concerned with the health of the individual, the family, populations, and the community (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2007). This unit focuses on applying the nursing process with the community as client. What is the role of the nurse in population-focused nursing? What does it mean to be a nurse who is responsible for the health of a community? Where does the nurse start in considering community? What is a healthy, competent community?

Healthy communities have “environmental, social, and economic conditions in which people can thrive” (Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations, 1999, p. 3). A healthy community is one in which residents are happy with their choice of location and which exhibits characteristics that would draw others to the location. The majority of community residents are relatively functional for their age and health status. What are other characteristics of a healthy community? Kotchian (1995) suggested that a healthy community would be a safe community with little crime, supportive interaction between families and neighborhoods, a healthy environment (e.g., clean air, clean water, safe food), good schools, available and good quality health care services, and a sense of community cohesion. Green and Kreuter (2005) identified affordable housing and the availability of employment as prerequisites for healthy communities.

Besides these factors that immediately and obviously affect health, many social circumstances and other less tangible issues affect community living. For example, high crime rates and high levels of poverty in a neighborhood can seriously affect the health and welfare of residents. Ervin (2002) suggested that a healthy economy is key to a functional, healthy population. Although difficult to quantify, most people can identify characteristics of a healthy community that would influence their decision to reside there (Box 15-1).

Community assessment: application to community/public health nursing practice

Assessment, the first step of the nursing process, forms the foundation for determining the client’s health, regardless of whether the client is an individual, a family, or a community. Nurses gather information by using their senses, as well as their cognition, past experiences, and specific tools. These data are analyzed to make diagnoses about the community’s health status and allow the nurse to answer the question, “How healthy is this community, or what are its strengths, problems, and concerns?”

The assessment process affords nurses the opportunity to experience what it is like to be in the community, to get to know its people and their strengths and problems, and to work with them in planning and implementing programs to meet their unique needs. Just as all individuals and families are different, communities, too, are different. What makes one community different from another? To understand, nurses must get to know the community, its people, its purpose, and how it functions. Assessment tools provide a framework, a method of systematically gathering important information to help the nurse and other health care professionals know the community.

How does the nurse become acquainted and familiar with a community? One way is to read about a community through newspapers, community histories, and objective statistical reports. Another way is to visit the community, talk to the people, and attend meetings—that is, be with the people. A visit to or a walk or a drive through the community provides a feel for the community that cannot be obtained from just reading about it. The walk or drive-through is frequently referred to as a windshield survey. Being in the community allows the nurse to subjectively experience a community and to learn how community members experience their community.

Take a moment to reflect on this scene:

What is it like for residents who live here? Would you like to live here? What kinds of things would lead you or others to want to live here?

In the preceding example of community, two neighborhoods are presented, geographically close but different. Who lives in the two neighborhoods? What would it be like to live in these communities? What would it be like to be a community health nurse responsible for the health of these communities? What type of nursing care do you think this community needs?

Before we go any further, we need to define community. What is the meaning of this term? Does community mean only the neighborhood in which one lives, or does it have other meanings?

Community defined

If you were to ask five people to define the word community, you would probably get five different answers: “a place where people dwell,” “a group of people with common interests,” “a place with specific boundaries.” Some people may speak about an academic community, a religious community, or a nursing community, and others may define community as the neighborhood or city in which they live. Depending on the circumstances, each definition is correct.

In this text, community is defined as an open social system that is characterized by people in a place who have common goals over time. The term is applicable to a variety of situations. A community includes a place and groups or aggregates. An aggregate is any number of individuals with at least one common characteristic (Williams, 1977). The terms population group and aggregate are synonyms for population (Williams, 1977). A population is a collection of individuals who share one or more personal or environmental characteristics, the most common of which is geographical location (Schultz, 1987). How a person defines community depends on the situation and that person’s purpose. To community health nurses working for a county health department, community might mean a geographical area and its residents (population) such as the county or health district to which they are assigned. This description is the classic definition of community. Nurses working with the homeless, older adults, or a special interest group (e.g., smokers) may define community as people with common characteristics (aggregate) within a specific place.

Literature Review

Community health literature offers a variety of definitions. Behringer and Richards (1996) described community as a web of people shaped by relationship, interdependence, mutual interests, and patterns of interaction. Shamansky and Pesznecker (1981) provided an operational definition of community considering the following three factors: (1) who (people factors), (2) where and when (space and time factors), and (3) why and how (for what purpose?). Ervin (2002) stressed that community assessments always occur at a particular time, for example, July 2011, or during the year 2012.

Anderson and McFarlane (2010) define community in terms of a core dimension (people) and eight subsystems: (1) physical environment, (2) education, (3) safety and transportation, (4) politics and government, (5) health and social services, (6) communication, (7) economics, and (8) recreation.

Other authors define community by describing types or categories. Communities may be geographically or socially bound (Hawe, 1994); categorized as emotional, structural, or functional (Archer, 1985); or defined in terms of relational and territorial bonds (Turner & Chavigny, 1988).

One of the most comprehensive definitions of the term community found in community health literature was formulated by Higgs and Gustafson (1985): “A community is a group of people with a common identity or perspective, occupying space during a given period of time, and functioning through a social system to meet its needs within a larger social environment.” This definition is most closely related to the concept of community discussed in this text.

Critical Components of a Community

For the purpose of this text, a community may be defined as a community if three critical components or defining characteristics are included: (1) people, (2) place, and (3) social interaction or common characteristics, interests, or goals. All communities contain all three of these components.

People

Population is the most obvious of the necessary community components. The number of people included in the community depends on the other two critical components. A population can be a relatively small number (a group of 20 pregnant adolescents enrolled in a clinic) or a large number of people (a city of one million). The ages, gender, race/ethnicity, religion, occupations, and socioeconomic status may be similar or diverse.

Place

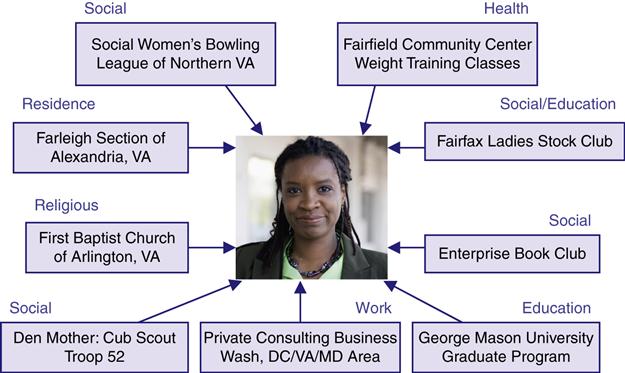

Traditionally, communities were described in relation to geographical area. However, population aggregates such as older adults, the poor, people with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), or any population in which the members share one or more common characteristics, goals, or interests are sometimes used to identify a community for assessment purposes. Therefore, communities may be defined by one of two designations: (1) geopolitical (spatial) or (2) phenomenological (relational). Figures 15-1 and 15-2 illustrate some geopolitical and phenomenological communities.

In geopolitical communities, place is designated by a geographical or political boundary. The people who live, work, learn, and play in the community constitute the population. In most suburban and urban geopolitical communities, the individuals know only some of the residents on a face-to-face, personal basis. In less densely populated rural areas, most people may know each other on a personal basis. (© 2011 Photos.com, a division of Getty Images. All rights reserved. A, Photos.com #200393342-001)

In phenomenological communities, place is designated by a sense of belonging among its members. Although all human communities exist in a physical place, the members of a phenomenological community are bound together by their interpersonal connectedness rather than by geography. For example, individuals may belong to the U.S. military community, even though they live throughout the entire world. A sense of belonging occurs in phenomenological communities such as clubs, schools, gangs, senior centers, businesses, and churches and other religious organizations.

Geopolitical

The geopolitical community is a spatial designation—a geographical or geopolitical area or place. This view is the most traditional in the study of community.

Geopolitical communities are formed by either natural or human-made boundaries. A river, a mountain range, or a valley may create a natural boundary; for example, the Chesapeake Bay separates Maryland into the eastern and western shores. Human-made boundaries may be structural, political, or legal. Streets, bridges, or railroad tracks may create structural boundaries. City, county, or state lines create legal boundaries. Political boundaries may be exemplified by congressional districts or school districts.

Why does a community/public health nurse need to be concerned about geopolitical boundaries? A geopolitical view of community focuses the nurse’s attention on the environment, housing, transportation, education, and political process subsystems. All of these elements are related to geographical locations as well as to the population composition and distribution, health services, and resources and facilities. Statistical and epidemiological studies are frequently based on data from specific geopolitical areas.

Phenomenological

Most people initially think of community in terms of geographical location. Another way of thinking about community is in terms of the members’ feeling of belonging or sense of membership, rather than geographical or political boundaries. Such a community is a phenomenological community, a relational rather than a spatial designation. A sense of place emerges through the members’ awareness of their experiences together. This place is more abstract than a geopolitical place but is just as real to its members. People in a phenomenological community have a group perspective that differentiates them from other groups. A group consists of two or more people engaged in an interdependent relationship that includes repeated face-to-face communication. A group’s identity may be based on culture, beliefs, values, history, common interests, characteristics, or goals. Examples of phenomenological communities include populations of people with common interests such as a common religious conviction or professional or academic interest; with common beliefs such as beliefs about human rights including women’s rights or racial equality; or with a common goal such as Students Against Drunk Driving (SADD), whose common goal is to decrease alcohol-related accidents among students who drive.

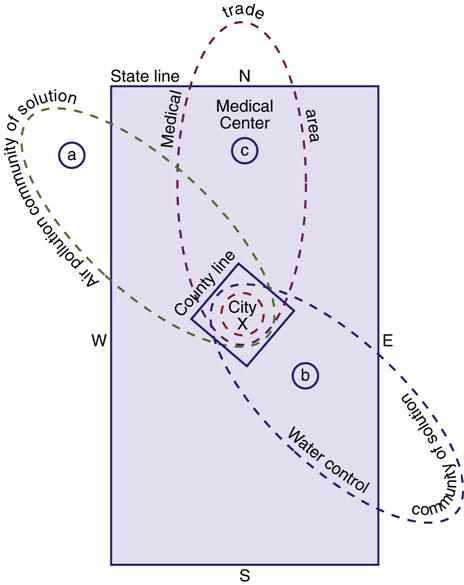

Another example of a phenomenological community is a community of solution. This type of phenomenological community has special significance for health planning. The National Commission on Community Health Services (1966) suggests that when health services are considered, the boundaries of each community are established by the boundaries within which a problem can be identified, dealt with, and solved. A community of solution includes (1) a health problem shed (i.e., an area that has similar health problems) and (2) a health marketing area (i.e., an area that has similar solutions to the problem or an adequate supply of health resources to meet the problem).

For example, an oil spill in the Chesapeake Bay would affect more than one county. Parts of several counties in Maryland and Virginia may be affected. All of the communities affected become the health problem shed. All of the communities that join together and pool their resources to meet the need create a health marketing area. Figure 15-3 illustrates one city’s communities of solution. The concept of a community of solution is especially important in coordinating health care and decreasing duplication and fragmentation of services.

Note that health solution boundaries extend beyond city, county, and state lines. A, Because of air currents, air pollution may be displaced to the northwest. B, Because of the topography of the land, the water and sewage drain toward the southeastern portion of the state, which constitutes another “health problem shed.” If the state and neighboring states joined together to solve the problem, this would constitute a health marketing area. C, A similar principle holds true for the medical trade area: the state emergency medical services system territory includes part of the adjoining state to the north. (Adapted from National Commission on Community Health Services. [1966]. Health is a community affair. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press.)

Social Interaction or Common Interests, Goals, and Characteristics

Communities, similar to families, have their own patterned interaction among individuals, families, groups, and organizations; this interaction varies from community to community depending on needs and values. In a geopolitical community, this interaction may go beyond talking to one’s neighbor and may include interactions with agencies and institutions within the community. In a phenomenological community, this attribute is inherent. A phenomenological community exists because of a common interest or feeling of belonging (Dreher & Skemp, 2011).

Each of us lives in a geopolitical community, but we may be members of several phenomenological communities. Figure 15-4 illustrates one individual’s community membership.

Basic community frameworks

Now that we have defined the concept of community, how do you approach or study the community as a client? There are many theoretical approaches to communities. Perspectives on community come from diverse fields of study, including anthropology, sociology, epidemiology, social psychology, social planning, and nursing. Community/public health nurses have adapted and used theories from other disciplines. Several frameworks that are especially helpful in community/public health nursing include developmental, epidemiological, structural–functional, and systems frameworks. Box 15-2 provides examples of frameworks used to study communities.

Nursing Theories Applicable to Community Assessment

Most nursing theories were developed for individual clients, not communities (Alligood & Marriner-Tomey, 2010; Hanchett, 1988). Many nursing theories view the community as the environmental system influencing individuals and families.

Only a few nursing theories view the community as client (Hamilton & Bush, 1988). Goeppinger and colleagues (1982) proposed the development of a community assessment tool using Cottrell’s characteristics (1976) of a competent community as a framework. Community competence is based on eight variables: (1) commitment, (2) self and other awareness and clarity of situation definitions, (3) articulateness, (4) communication, (5) conflict containment and accommodation, (6) participation, (7) management of relations with the larger society, and (8) machinery for facilitating participant interaction and decision making (Cottrell, 1976; Moorhead et al., 2008). Most of these characteristics of a competent community are community processes that can contribute to the inclusion and participation of community members.

The theories of Johnson (1980), Roy (Roy & Andrews, 1999), King (1981), Neuman (Neuman & Fawcett, 2002), and Watson (Rafael, 2000) may be used to view the community as client. All theories are based, in part, on general systems theory. As discussed in Chapter 1, general systems theory can be applied to any social system, including a community. Table 15-1 presents views of the health of a community from the perspectives of these nursing theories.

Table 15-1

Perspective on the Health of Communities in Selected Nursing Theories

| Theorist | Health of a Community |

| Dorothy Johnson | Successful community functioning and adjustment to environmental factors |

| Sister Callista Roy | Effectiveness of the community in accomplishing its functions and adapting to external stimuli |

| Imogene King | Quality interactions between individuals, groups, and the entire community that contribute to community functioning and development |

| Betty Newman | Competence of the community to function and maintain balance and harmony in the presence of stressors |

| Jean Watson | A healthy community is a holistic community, one which is able to integrate social and personal resources and capacities to attain or maintain health for its members |

Data from Anderson, E., McFarlane, J., & Helton, A. (1986). Community-as-client: A model for practice. Nursing Outlook, 34(5); Hanchett, E. (1988). Nursing frameworks and community as client—Bridging the gap. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; Alligood, M. & Marriner-Tomey, A. (2010). Nursing theorists and their work (7th ed.). St Louis: Mosby; Dixon, E. (1999). Community health nursing practice and the Roy Adaptation Model. Public Health Nursing, 16(4), 290-300; Rafael, A. R. F. (2000). Watson’s philosophy, science, and the theory of human caring as a conceptual framework for guiding community health practice. Advances in Nursing Science, 23(2), 34-49.

Nursing Frameworks for Community Assessment and Practice

Several frameworks have emerged that are either nurse developed or used in public health practice. Two such frameworks view the community as partner. Anderson and McFarlane’s (2010) Community as Partner model and Helvie’s (1998) Energy Theory are nurse-developed frameworks. Both views consider community as a network of interrelating relationships, characteristics, and supports. Using these models, community/public health nurses act in partnership with others (health care professionals and community members) to address the community’s health concerns (ANA, 2007). Several models are based on the epidemiological framework. Two of these models have particular value to community health nurses: the GENESIS and MAPP models. All four models are influenced, to some degree, by systems theory and are briefly summarized in Box 15-3.

Systems-based framework for community assessment

Although many useful strategies and frameworks are available for community assessment, the assessment tool used in this text is based on systems theory. A systems framework ensures that the dynamics within and external to each system, or community, are identified and explored. In addition, the tool incorporates aspects of the structural–functional framework (which identifies community goals and analyzes internal community functioning) and the epidemiological framework (which analyzes the health status of the people, or populations, within the community).

The advantage of this systems-based community assessment tool is that it incorporates multiple frameworks simultaneously. If considered useful, a developmental framework can be incorporated to explore the history of the community.

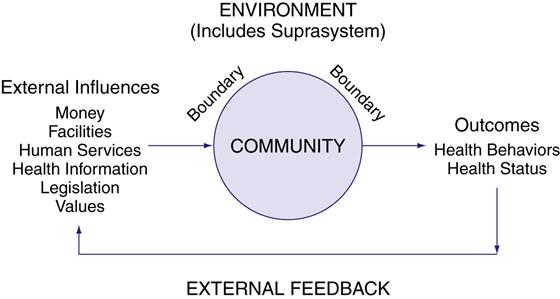

Overview of Systems Theory

A systems framework views the community as a dynamic model in which the community is constantly in the process of responding and adapting to internal and external stimuli. The responses are aimed at developing and maintaining a sense of balance or equilibrium. The systems model (Figure 15-5) serves as a tool to help the nurse identify, collect, and organize appropriate data, including the critical components and their relationship to each other.

The components of the systems model for both geopolitical and phenomenological communities are the same and consist of the following:

• Goals: purpose or reason for which the community exists

• Characteristics: physical and psychosocial characteristics of the community that affect behavior

• External influences: resources or stressors from the suprasystem

• Internal functioning: structures and processes of the community, divided into four functional subsystems: economy, polity, communication, and values (University of Maryland School of Nursing, 1975)

• Feedback: information that is returned to the system regarding its functioning

Although the components of geopolitical and phenomenological communities are the same, the types of data collected and the resources for those data vary. The environment external to the community in Helvie’s model (1998) is referred to as the suprasystem in our model (von Bertalanffy, 1968). For the discussion on the holistic assumptions and review of general systems theory, refer to Chapter 1.

Components to Assess

Box 15-4 presents the basic systems model for community assessment, identifies important data to collect, and suggests possible data sources. Website Resource 15A ![]() expands the information on the tool in Box 15-4. The tool differentiates how the model would be used for both geopolitical and phenomenological community assessments, and suggests some of the questions nurses would need to ask. The following discussion examines the important features in each component in the assessment process.

expands the information on the tool in Box 15-4. The tool differentiates how the model would be used for both geopolitical and phenomenological community assessments, and suggests some of the questions nurses would need to ask. The following discussion examines the important features in each component in the assessment process.

Boundaries

The essential first step in community assessment is identifying the boundaries or parameters of the community. Remember that a community is defined in terms of the three critical components: people, place, and social interaction or common interests. The definition of a community determines its boundaries. Consider the boundary as the skin or outside limit of the community. Establishing the boundary helps the nurse determine what data will be collected and considered internal to the community, in other words, community information. Defining the boundary also identifies the suprasystem, the environment outside the community. Data collected from the suprasystem are considered external influences, or inputs, and may impact or influence the community.

Boundaries, similar to the skin of an individual, maintain the integrity of the system and regulate the exchange between a community and its external environment, the suprasystem. Boundaries of a geopolitical community are spatial and concrete; they can be natural or human made, as discussed earlier. Because the boundaries of geopolitical communities are real and concrete, they are often visible on maps. For example, the Potomac River and the Maryland state line can be visualized on a map as indicators of the boundaries of Washington, DC. The Rocky Mountains divide the western part of the United States from the Great Plains. The river and mountains are natural boundaries and the state line a human-made boundary.

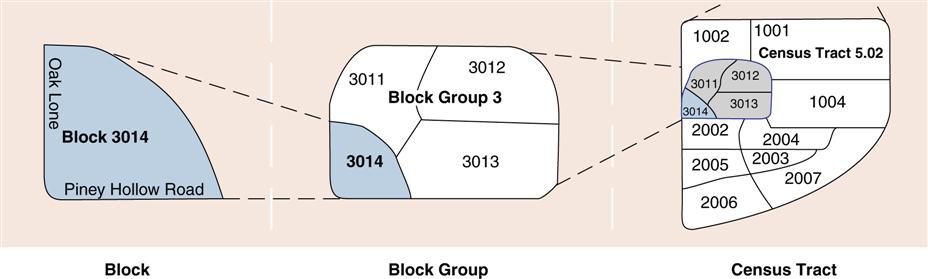

Another type of human-made boundary is a census tract. The U.S. Census Bureau divides the United States into census tracts for the purpose of reporting demographic data about the U.S. population every 10 years. Census tract data are valuable for health planning. Census tract maps are available in libraries and health departments. Figure 15-6 illustrates how an area is incorporated into a census tract. Website Resource 15B ![]() provides additional information on census tracts.

provides additional information on census tracts.

The boundaries of phenomenological communities are more relational or conceptual than are geopolitical boundaries and usually relate to the reason the community exists or to the criteria for membership. To determine the boundary of a phenomenological community, the following questions would be asked:

For example, the boundary of the nursing community would be its criterion for membership—that is, the person must be a nurse to belong. The boundary of a Cub Scout pack would be the criteria of age (7 to 10 years old) and gender (boys)

A nurse assessing the community might determine some characteristics from the data provided. This community is a phenomenological community; it is an aggregate of frail older adults attending Morgan Center. The criteria for membership (65 years of age and older, residents of Allen County, frail, and continent) determine the boundaries. Another way to define the community would be to view the Morgan Center in its entirety, including frail older adults, the site manager, and the staff. In this case, the criteria for membership change to persons who work at or attend the center. Either definition is correct, depending on the reason or purpose for the assessment.

As you can see, the parameters of the community must be defined because they determine what data will be collected. In the first situation, the nurse will collect data about frail older persons only, and the site manager and the staff will be external influences to the community; in the second example, the nurse will collect data about frail older persons, the site manager, and the staff as part of the community. Boundary definition is especially important when examining the external influences and the internal functioning of a community.

Permeability of Boundaries

The boundaries of any system may be relatively permeable (open) or impermeable (closed). For example, entrance or membership into a religious community may be contingent on accepting certain beliefs and rituals, making the boundary impermeable to someone who does not hold these beliefs. In a phenomenological community, the criteria for membership often define the boundary’s permeability or openness. A geographical community that has a gated entrance and homes that cost $350,000 or more is impermeable to people with an annual income of $25,000 to $30,000. Communities with greater variety of housing prices and rental units would be open to more people; thus the boundaries would be permeable.

The openness or closeness of a community has implications for health planning. A closed, rigid system is resistant to change, whereas an open, flexible system is more receptive to change and to help from the health care delivery system.

Suprasystem

Once you have determined the boundary of the community, anything outside the boundary becomes the suprasystem. No system (individual, family, or community) can exist in isolation. Therefore, every client system operates within a larger system. The larger system, the suprasystem, is defined as the environment external to, or outside of, the community that affects the community system. The suprasystem of a geopolitical community is concrete. For example, the immediate suprasystem of Ridgely’s Delight, a neighborhood in Baltimore, is the city of Baltimore. The suprasystem of Baltimore is the state of Maryland. Identifying a specific suprasystem for a geopolitical community is usually easier than it is in a phenomenological community.

In a phenomenological community, the suprasystem becomes anything outside of the community that affects or is affected by the community. Identifying a single suprasystem for a phenomenological community is sometimes difficult; many suprasystems may be found. For example, what is the suprasystem for an aggregate such as the older individuals in Orange County? It might be the Orange County Office on Aging, the entire Orange County government, the American Association of Retired Persons, or the Orange County Social Security Office, all four of these entities, or these four entities and still others. The sources of external influences from the larger society must be examined, such as legislation, services, and money that influence (positively or negatively) the older adult community. For some phenomenological communities, however, identifying a specific suprasystem may be possible. For example, Girl Scout Troop No. 201 is a phenomenological community; its suprasystem is the Girl Scouts of Central Ohio.

Goals

Goals of communities vary with the type of community, but in general, they are focused on maximizing the well-being of members, promoting survival, and meeting the needs of the community members. What are the goals of the community in which you live? Are they to provide safe housing for residents? One goal of the Morgan Senior Center is to provide socialization for its members. The community health nurse can assess the goals of the community by asking questions such as, “What is the purpose of the community?” A written statement of the community’s philosophy and goals, if available, is another source.

Characteristics

Characteristics are the physical, biological, and psychosocial factors of the community. These characteristics are often referred to as demographics. Characteristics are usually not easily changed, or they change slowly.

Physical Characteristics

Physical characteristics include (1) the length of time the community has been in existence, (2) pertinent demographic data about the community’s members (e.g., age, race, gender, ethnicity, education, income, housing, density of population), and (3) physical features of the community that influence behavior.

The length of time the community has been in existence (the age of the community) has implications regarding stability, health care services, and needs. On the one hand, a very new community may have few services simply because supply has not caught up with demand. On the other hand, communities that have been in existence for a long time may have many resources, or they may have resources that reflect past population needs but not the current needs (if population shifts have occurred).

Pertinent demographic data such as age, race, gender, ethnicity, and density of the population have significant meaning in the planning of health care services. By looking at the age, race, and gender of members of the community, the community/public health nurse can make some inferences about possible health care needs. A community with a large population of older individuals will have very different needs from persons of a community with a predominantly young population. Generally, older individuals need more services than do younger persons. Race is a factor in certain diseases (e.g., sickle cell anemia in the African American population; Tay-Sachs disease in Jewish populations). A population with an unusually high number of women will need more women’s health care services, and a community with a high number of adults may need blood pressure screening programs to detect early hypertension.

Ethnicity is reflected in customs, beliefs, and values and may affect how the community addresses certain health practices (refer to Chapter 10). The community/public health nurse must understand these customs and beliefs when assessing needs and planning interventions. In some areas, the cultural and ethnic backgrounds of the population have become the basis for the community. Some cities have sections that reflect the ethnic and cultural heritage of certain groups (e.g., Little Italy or Chinatown in San Francisco). Groups such as the Sons of Norway, the Sons of Italy, and the Polish Home Club have formed phenomenological communities on the basis of their ethnic and cultural heritages.

The type, condition, and amount of housing and density of the population are environmental factors that have implications for health. Crowded living conditions have long been associated with the increased transmission of some communicable diseases (e.g., tuberculosis, pediculosis). Also important to note is the condition of the housing and whether housing is available and financially accessible to people in the community. The type and condition of housing may say a lot about the resources and values of the people living in the community.

In a phenomenological community, the environment or the place in which the group meets might be examined. This review takes into consideration the environmental factors and the aesthetics that contribute to or interfere with members’ ability to feel comfortable in the physical environment.

Physical features of the community can influence the community’s behaviors. A community with fences around all houses demonstrates preference for privacy and may imply little social interaction or the presence of dogs or pools. A school with open classrooms influences the interaction among students. Other physical features such as living or working in a community with toxic substances may influence the level of health of the residents or workers.

Psychosocial Characteristics

Psychosocial characteristics that affect the emotional tones of the community include religion, socioeconomic class, education, occupation, and marital status. Some ways these characteristics may affect health behavior include the following:

• Socioeconomic level: Poverty reduces access to health care services and increases health risks (see Chapters 4 and 21).

Collecting demographic information can provide the nurse with some idea of the possible health needs of the community. Looking at a number of people with common characteristics and planning programs to meet their unique health care needs are the basis for aggregate/population health planning. Sources of demographic information are identified later in Tools for Data Collection.

External Influences

All communities have external influences that affect their functioning. External influences are matter, energy, and information that come from outside the community—that is, from the suprasystem. External influences may be either resources (assets or strengths) or demands (liabilities or weaknesses) on the community and may be mandated (required) or voluntary. Some of the most important external influences are money, facilities, human services, health information, legislation, and values of the suprasystem. Some of the areas to explore for each of these influences are summarized here:

Data Sources for Suprasystem Information

Because the external influences come from the suprasystem, obtaining data about the suprasystem is important. Where can these data be found? A wealth of information is provided by review of the suprasystem budget, local telephone book and newspapers, health or human service directories, and information and referral services; systematic tours of services and agencies; interviews with members of the community; and review of legal and policy and procedure books.

Internal Functions of the Community

Internal functioning of the community occurs through its internal structures and processes. For the purpose of data collection and analysis, the tool examines four functional areas: economy, polity, communication, and values (University of Maryland School of Nursing, 1975). Resources and demands may be found within each of these subsystems.

When assessing individual human functioning, it is essential to determine areas of strength as well as areas of need. Nurses work with individuals to build on their strengths to overcome and adapt to health deficits. The same is true when assessing a community. Asset models of community assessment stress the positive abilities and capacities of communities to identify their own health problems and plan solutions. Such a model encourages community participation and has the potential to empower communities. Community resiliency is the ability of a community to use its assets and resources to adapt to adversity and improve its capacity (Kulig, 2000; Moorhead et al., 2008; Racher & Annis, 2008). Community capacity may include social participation, sense of community, networks among organizations, skills, knowledge, and leadership necessary “to promote future community health and welfare” (Trickett et al., 2011, p. 1411).

Economy

The goal of the economy subsystem is production and distribution of goods and services. Economy includes categories such as human services; money; facilities, equipment, and goods; and education. These factors are the same as those discussed in the assessment of external influences. However, the factors to examine here are those within the community itself.

1. Human services. Services available within the community may be either formal (e.g., nurses and physicians) or informal (e.g., volunteers). Questions to ask include the following:

• What human services are available within the community to meet the community’s health needs?

• Are the human services responsive to the needs of the community?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree