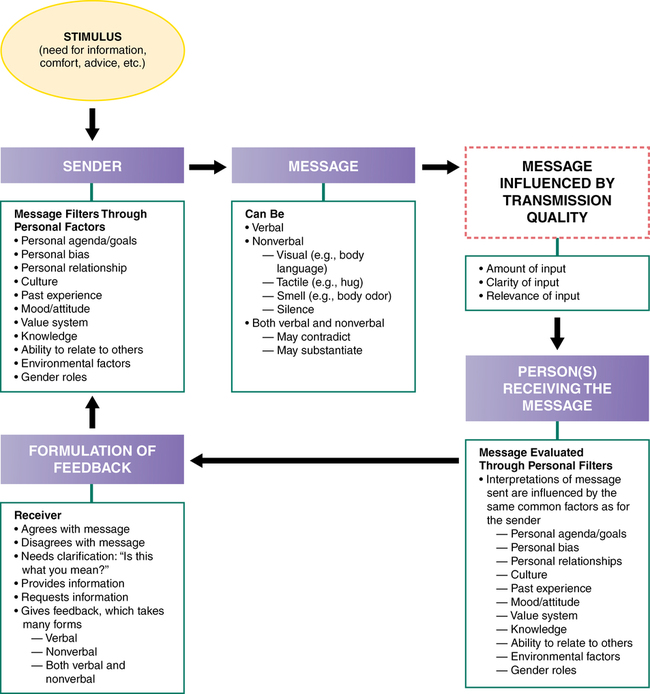

CHAPTER 9 1. Describe the communication process. 2. Identify three personal and two environmental factors that can impede communication. 3. Discuss the differences between verbal and nonverbal communication. 4. Identify two attending behaviors the nurse might focus on to increase communication skills. 5. Compare and contrast the range of verbal and nonverbal communication of different cultural groups in the areas of (a) communication style, (b) eye contact, and (c) touch. Give examples. 6. Relate problems that can arise when nurses are insensitive to cultural aspects of patients’ communication styles. 7. Demonstrate the use of four techniques that can enhance communication, highlighting what makes them effective. 8. Demonstrate the use of four techniques that can obstruct communication, highlighting what makes them ineffective. 9. Identify and give rationales for suggested (a) setting, (b) seating, and (c) methods for beginning the nurse-patient interaction. 10. Explain to a classmate the importance of clinical supervision. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis Novice psychiatric practitioners are often concerned that they may say the wrong thing, especially when learning to apply therapeutic techniques. Will you say the wrong thing? Yes, you probably will, but that is how we all learn to find more useful and effective ways of helping individuals reach their goals. The challenge is to recover from your mistakes and use them for learning and growth (Sommers-Flanagan & Sommers-Flanagan, 2013). Communication is an interactive process between two or more persons who send and receive messages to one another. The following is a simplified model of communication (Berlo, 1960): 1. One person has a need to communicate with another (stimulus) for information, comfort, or advice. 2. The person sending the message (sender) initiates interpersonal contact. 3. The message is the information sent or expressed to another. The clearest messages are those that are well-organized and expressed in a manner familiar to the receiver. 4. The message can be sent through a variety of media, including auditory (hearing), visual (seeing), tactile (touch), olfactory (smell), or any combination of these. 5. The person receiving the message (receiver) then interprets the message and responds to the sender by providing feedback. Figure 9-1 shows this simple model of communication, along with some of the many factors that affect it. Effective communication in therapeutic relationships depends on nurses’ (1) knowing what they are trying to convey (the purpose of the message), (2) communicating what is really meant to the patient, and (3) comprehending the meaning of what the patient is intentionally or unintentionally conveying (Arnold & Boggs, 2011). Peplau (1952) identified two main principles that can guide the communication process during the nurse-patient interview, which is discussed in detail later in this chapter: (1) clarity, which ensures that the meaning of the message is accurately understood by both parties “as the result of joint and sustained effort of all parties concerned,” and (2) continuity, which promotes connections among ideas “and the feelings, events, or themes conveyed in those ideas” (p. 290). • Communicate our beliefs and values • Communicate perceptions and meanings • Convey interest and understanding or insult and judgment • Convey messages clearly or convey conflicting or implied messages • Convey clear, honest feelings or disguised, distorted feelings It is often said, “It’s not what you say but how you say it.” In other words, it is the nonverbal behaviors that may be sending the “real” message through the tone or pitch of the voice. It is important to keep in mind, however, that culture influences the pitch and the tone a person uses. For example, the tone and pitch of a voice used to express anger can vary widely within cultures and families (Arnold & Boggs, 2011). The tone of voice, emphasis on certain words, and the manner in which a person paces speech are examples of nonverbal communication. Other common examples of nonverbal communication (often called cues) are physical appearance, body posture, eye contact, hand gestures, sighs, fidgeting, and yawning. Table 9-1 identifies examples of nonverbal behaviors. TABLE 9-1 Facial expression is extremely important in terms of nonverbal communication; the eyes and the mouth seem to hold the biggest clues into how people are feeling through emotional decoding. Eisenbarth and Alpers (2011) tracked how long participants looked at various parts of the face in response to different emotions. Participants initially focused on the eyes more frequently when looking at a sad face, and they initially focused on the mouth more frequently when looking at a happy face. Like sadness, anger was more frequently decoded in the eyes. When presented with either a fearful or neutral expression, there was an equal amount of attention given to both the eyes and the mouth. Shawn Shea (1998), a nationally renowned psychiatrist and communication workshop leader, suggests that communication is roughly 10% verbal and 90% nonverbal. The high percentage he attributes to nonverbal behaviors may best describe our understanding of feelings and attitudes and not general communication. After all, it would be difficult to watch a foreign film and completely understand its meaning based solely on body language and vocal tones; however, nonverbal behaviors and cues influence communication to a surprising degree. Communication thus involves two radically different but interdependent kinds of symbols. Some elements of nonverbal communication, such as facial expressions, seem to be inborn and are similar across cultures (Matsumoto, 2006; Matsumoto & Sung Hwang 2011). Some cultural groups (e.g., Japanese, Russians) may control their facial expressions in public while others (e.g., Americans) tend to be open with facial expressions. Gender also plays a role in facial expressions; men are more likely to hide surprise and fear while women control disgust, contempt, and anger. Messages are sent to create meaning but also can be used defensively to hide what is actually going on, create confusion, and attack relatedness (Ellis et al., 2003). Conflicting messages are known as double messages or mixed messages. One way a nurse can respond to verbal and nonverbal incongruity is to reflect and validate the patient’s feelings. For example, the nurse could say, “You say you are upset you did not pass this semester, but I notice you look relaxed. What do you see as some of the pros and cons of not passing the course this semester?” Bateson and colleagues (1956) coined the term double-bind messages. They are characterized by two or more mutually contradictory messages given by a person in power. Opting for either choice will result in displeasure of the person in power. Such messages may be a mix of content (what is said) and process (what is conveyed nonverbally) that has both nurturing and hurtful aspects. The following vignette gives an example. Peplau emphasized the art of communication to highlight the importance of nursing interventions in facilitating achievement of quality patient care and quality of life (Haber, 2000). The nurse must establish and maintain a therapeutic relationship in which the patient will feel safe and hopeful that positive change is possible. • Observing the patient’s nonverbal behaviors • Understanding and reflecting on the patient’s verbal message • Understanding the patient in the context of the social setting of the patient’s life • Detecting “false notes” (e.g., inconsistencies or things the patient says that need more clarification) • Providing feedback about himself or herself of which the patient might not be aware “Tell me more about your relationship with your wife.” “Describe your relationship with your wife.” “Give me an example of how you and your wife don’t get along.” Asking for an example can greatly clarify a vague or generic statement made by a patient. Nurse: ”Give me an example of one person who doesn’t like you.” Patient: ”Everything I do is wrong.” Nurse: ”Give me an example of one thing you do that you think is wrong.”

Communication and the clinical interview

The communication process

Verbal and nonverbal communication

Verbal communication

Nonverbal communication

BEHAVIOR

POSSIBLE NONVERBAL CUES

EXAMPLE

Body behaviors

Posture, body movements, gestures, gait

The patient is slumped in a chair, puts her face in her hands, and occasionally taps her right foot.

Facial expressions

Frowns, smiles, grimaces, raised eyebrows, pursed lips, licking of lips, tongue movements

The patient grimaces when speaking to the nurse; when alone, he smiles and giggles to himself.

Eye expression and gaze behavior

Lowering brows, intimidating gaze

The patient’s eyes harden with suspicion

Voice-related behaviors

Tone, pitch, level, intensity, inflection, stuttering, pauses, silences, fluency

The patient talks in a loud sing-song voice.

Observable autonomic physiological responses

Increase in respirations, diaphoresis, pupil dilation, blushing, paleness

When the patient mentions discharge, she becomes pale, her respirations increase, and her face becomes diaphoretic.

Personal appearance

Grooming, dress, hygiene

The patient is dressed in a wrinkled shirt, his pants are stained, his socks are dirty, and he is unshaven.

Physical characteristics

Height, weight, physique, complexion

The patient is grossly overweight, and his muscles appear flabby.

Interaction of verbal and nonverbal communication

Communication skills for nurses

Therapeutic communication techniques

Active listening

Clarifying techniques

Exploring.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Communication and the clinical interview

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access