Chapter 10. Communicating with children and their families

Janet Matthews

LEARNING OUTCOMES

• Outline the development of communication from birth to adolescence.

• Discuss factors that have an impact on communication with children and families in the context of health care.

• Discuss communication strategies that facilitate family coping when communicating a serious diagnosis.

• Use relevant literature and research to identify good practice when working with children and families when the child has a life-limiting illness or disability and communication barriers.

PowerPoint

PowerPointAccompanying PowerPoint presentations

Learning outcome 1 relates to presentation Part 1: Child Development and Part 2: Eyesight, speech, language and hearing difficulties, which provides useful website links to valuable information for children, families and health professionals. It also contains information on the role of speech and language therapists.

The remaining learning outcomes relate to Part 3: Communication: the healthcare context.

Introduction

Communication is instinctive from the moment of birth as the infant attempts to communicate with adults (Fig. 10.1), which is essential for development and the communication of need initially at a basic level. To promote child development, health and family integrity, the nurse must learn how children and families communicate but also how to communicate effectively with children of all ages and their families. This chapter will enable the nurse to identify effective communication strategies to ensure children, young people and their parents/carers have the information they need in the appropriate format. Providing clear, understandable information helps the child and family cope with alterations in health by enabling them to maintain control within healthcare contexts. This chapter is designed to help nurses fulfill this role.

|

| Fig. 10.1 Engaging with mother 10 minutes after birth. |

Development of communication skills from conception to adolescence

Beginning life with a rich innate structure, infants begin to change their understanding of persons, themselves and others, being transformed through inter-personal interactions. As infancy comes to an end infants appreciate they are not alone or unique, living as psychological beings, among other psychological beings in the world

(Metzoff & Moore 1998 p 62).

The quality of human interaction at this crucial stage of development impacts on the infant perception of self and how they fit in, a process which begins in utero.

Before we are born

Research by Spence & DeCasper in 1986 indicates that, before birth, babies can hear and recognise their mother’s voice. During pregnancy when mothers repeatedly recited stories aloud, following birth their neonatal sucking pattern changed on recognition of their mother’s voice demonstrating their ability to differentiate their mother’s voice from two other story tellers (Zigler & Stevenson 1993).

www

www

www

wwwFind out more about DeCasper’s Research:

Neonatal imitation

Several studies in the 1970s demonstrate that neonatal imitation is a ‘robust phenomenon’ that can be observed from birth (Heimann 1998). This is believed to be due to their innate social motivation to interact, especially in a face-to-face position (Heimann 1998), which takes place within what Kugiumutzakis(1998) describes as the neonatal–maternal ‘intersubjective companion space’.

Learning to speak

Between the first and second year of life understanding and production of speech emerge (Zubrick et al 2007). Learning to speak is dependent on exposure to human language and feedback from adult pleasure. This reinforces infant achievements (touch, smiling, play, reciprocal communication, praise) and correction (calley, 1991 and Zubrick, 2007; Fig. 10.2). Infants are surprisingly sensitive to the quality of communication and seem to understand the significance of different types of communication (Murray 1998). Two-month-old infants demonstrate signs of let-down and disengagement when a happy mother suddenly becomes still and expressionless. Ongoing interactive engagement with an adult is essential to their development.

|

| Fig. 10.2 Face to face. |

First sounds

The speed of language acquisition mystifies linguists, who cannot fully explain ‘the apparent ease with which almost all babies acquire essential structure of one or more languages in their first three years’ (Whitehead 2000 p 1). The real mystery is why it becomes increasingly difficult for a child to develop language skills as they grow older. Unlike animals, children are born with the biological mechanism to enable them to articulate words and the mental processing ability that enables them to isolate speech from other sounds, process and reproduce this information (Zigler & Stevenson 1993). Newborns are particularly receptive to the human voice and, as early as 2 months old, they will respond differently to the mother’s voice distinguishing between different sounding words (Zigler & Stevenson 1993). The infant’s inner adoration and desire to communicate is reciprocation of the love and adoration communicated by the adult, drawing the infant into the world of language (Mayall, 1996 and Williams, 2003). Older siblings also contribute to the development of the young infant (Fig. 10.3).

|

| Fig. 10.3 Older siblings contribute to the development of a young infant. |

The immature sound-making skills of the infant constantly change, making it difficult to identify their first word. However, their early sounds are not random – crying begins at birth, cooing by the end of the first month and babbling begins at around 6 months (Oller 1980). It is believed that the repetitiveness of one syllable, e.g. ‘ba ba ba’, exercises and thus develops the muscles of articulation. Furthermore, the tone and pitch of babbling seems to differ in keeping with the tone and pitch of the language to which the child is exposed (Zigler & Stevenson 1993). Initially babbling can mask deafness but this will diminish if the infant cannot hear feedback. If deafness is not detected early the child will have more difficulty learning to speak. Deaf infants who are signed to from an early age develop sign language at a similar pace to the hearing child who is learning to speak. Early assessment and intervention by a speech and language therapist is very important.

PowerPoint

PowerPoint

PowerPoint

PowerPointFor more information see PowerPoint presentation Part 2: Eyesight, speech, language and hearing difficulties

The speed of language acquisition is variable and individual to each infant and context. Many studies cited by Whitehead (2000) show that a true word (one that is repeated spontaneously in the same context) can be produced from 9 months of life, although this usually takes place between 12 and 18 months. The first early word sounds are personal to the infant and recognised by the carer as a statement of interest or a specific request. Single words (e.g. ‘dink’ or ‘joo’) are used to transmit the meaning of a sentence ‘give me a drink of juice’. The words are often combined with actions (e.g. banging something), which communicates urgency and determination (Zigler & Stevenson 1993). Parental understanding of the meaning and the context of early words is vital to the child’s continuity of development.

Making sense of the world: 1–2 years

The speed and complexity with which infants combine words varies and is generally based on their need to get things done, to involve others or to comment. Emphasis in first sentences is usually placed on the main object requested, e.g. ‘book ma ma read’. Communication increasingly becomes a means of exploration and development of personality. Children then use language to share their new experiences with us. Language enables children to think in a symbolic way, which is the principle underpinning learning words using pictures in books and surroundings. Symbolic language is very important for children who have communication difficulties associated with deafness or blindness (Whitehead 2000). Sign language and touch are essentially symbolic, enabling children who are hearing or sight impaired to make sense of their experiences, observations and feelings as they interact socially with others.

Exploring the ‘big wide’ world: 2–5 years

By the age of two, children have become talkers or signers and communication enables infants to explore who they are (Bruce 2001) and where they fit in the bigger picture. Between 2 and 4 years of age children start to improve their grammar, sorting out singular and pleural differences and past tense by adding ‘s’ and ‘ed’ (Williams, 2003 and Zubrick, 2007). Whitehead (2000) states that spontaneous errors created as the child tries to correct early words, e.g. mouses and goed, are evidence of the ability of a child’s mind to process and produce the rules of language.

In the preschool years, children start to use joining words (‘because’, ‘and’, ‘if’) as they begin to understand cause and effect, sequencing of events, trial and error (Whitehead 2000). Their increasing ability to use words like ‘why’, ‘how’, ‘where’, ‘who’ and ‘what’ is essential to their cognitive development.

Edwards (1998) emphasises that other ‘relational motivations’, which develop from an early stage, take interaction beyond the boundaries of attachment as the child begins to engage in meaningful reciprocal communication within small groups. The child’s vocabulary increases to include words that enable him or her to share feelings and to explore how others are feeling. Dunn (1998) conducted longitudal research, which measured the child’s ability to correctly interpret emotions (happiness, anger, fear, sadness) related to various situations. This evidence, outlined below, is vital to the promotion of child and family attachment.

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practiceNaturalistic observation longitudinal research Dunn (1998)– 50 2-year-old infants were observed interacting with their mothers and older siblings at home. The results indicated that children had a greater understanding of others at 40 months old if the following observations had been made when they were 24 months old:

• frequently observed talking to family members about their feelings

• engaging in cooperative interaction with their siblings including social pretend play

• exposed to greater emotional intensity, intimacy and frequency of the interaction

• their mothers were more likely to engage in frequent controlling behaviour with older siblings.

The results suggest that personal experience and interest in how parents interact with siblings plays a key role in the development of emotional understanding. Further observation of the children over the next few years revealed that, between 33 and 47 months, talk about feeling to siblings quadrupled while talking to mothers declined. This study reflects the speed at which children develop the capacity to interact with others who, unlike a mother, may not always respond sensitively to them.

Zubrick et al (2007) undertook research to identify factors associated with Late Language Emergence (LLE) beyond 24 months. In a large longitudinal study 1880 (85% of the 2224 participants) returned completed questionnaires providing information on family, maternal, child characteristics and social/economic data. They also answered specific information on the infant’s language development. The results suggest the following factors may significantly increase the likelihood of LLE in an infant:

• a family history of LLE

• being born into a larger family

• neonatal low birth weight or born before 37 weeks gestation.

Surprisingly maternal characteristics (age at childbirth, employment, education, smoking, level of stress or depression) or family functioning demonstrated no statistical significance. Zubrick et al (2007) conclude that neurobiological and genetic factors are stronger determinants of LLE than maternal and family psycho-socioeconomic factors.

The primary school years: 5–12 years

Once the child starts school, language development is increasingly influenced by the wider social, cultural experience and literacy. Increasing diversity of experience influences social and moral development characterised by the child’s attitude and behaviour towards others. Studies by Braten (1998) support the theory that children who, when distressed, have been recipients of affective care will respond caringly to others in distress. Studies show that children who have been victims of neglect or physical abuse are more likely to demonstrate indifference, fear or aggression (George & Main 1979, Main & George 1985, Klimes-Dogan & Kistner 1990; all cited by Edwards 1998). Childhood influences are not always positive and as a result children learn to use swear words, foul language and give verbal abuse, presenting a challenge to their families, teachers and healthcare providers. A study by Wilson et al (2003) showed that children between 2 and 4 years commonly told lies to cover up wrong-doing or to control another person’s behaviour (Wilson et al 2003). Some children lie about their health to avoid going to school or undertaking daily chores. They may lie to conceal an illness or injury due to fear of painful interventions, e.g. tetanus injection, which could have serious implications.

The prevailing characteristics and attitudes in the family become the basis of unwritten rules, which are part of the child’s primary socialisation. The child can learn dysfunctional values and ways of communicating with others, which negatively affect the development of all members of the family (Friedman 1992). Dysfunctional communication in families is likely to influence how the child and family communicate with health professionals. Families who have closed dysfunctional patterns of communicating will have more difficulty coping, which may delay psychosocial recovery (Townley & Welton 2000).

Scenario

Scenario

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practice

Scenario

ScenarioBrian is a 2nd year student nurse on placement on an acute medical paediatric ward. In his peer reflective group he describes an incident which caused him great concern.

A 5-year-old boy was admitted for investigations of failure to thrive. He seemed to be allergic to so many things. On the handover I was allocated to look after him. I was warned that he was rude and abusive and that his mother and father were also troublesome.

The nurse in charge suggested I speak to them only when spoken to and generally watch my back. I was really anxious when approaching the family but I saw the boy had a book on Manchester United football club so I asked him who his favourite player was and we had a good chat. He was cheeky at times but I discovered that he had a good sense of humour. His mother really appreciated the time I spent talking to her son, which enabled her to go out for a cigarette. Other students also got on well with the family. The mother and child continued to be rude and abusive to the registered nurses and doctors.

Reflect on your practice

Reflect on your practiceIdentify and discuss the issues. In a similar situation how would you react?

The ‘company-they-keep’ hypothesis emphasises that adults who engage with children from an early age must recognise that they play a part in the development of prosocial or antisocial behaviour towards peers, which may continue throughout life (Edwards 1998). Modelling positive behaviour for the developing child is the responsibility of all those who work with children.

The teenager: 13–adulthood

The ongoing development of good communication skills throughout the adolescent years is problematic if the acquisition of language and literacy are not well established at this point. David Bell, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Schools, stated:

Far too many young people reach the end of their compulsory schooling with inadequate basic skills

The maturity of the adolescent is closely related to communication. Problems with self-esteem may be the result of a whole range of issues related to schooling and family life. General lack of confidence and unhappiness about the onset of puberty also impacts on the quality of interaction with some teenagers.

Activity

Activity

Activity

ActivityStudy Figure 10.4. How is this 12-year-old girl, in her bedroom feeling?

‘Just leave me alone please’

‘I want to watch my favourite programme without being pestered by my big brother’

‘Why does everyone assume I am sad when I just want some space to myself?’

• Consider the danger of observing but not listening to her.

|

| Fig. 10.4 What is being communicated? |

Family communication patterns will either exacerbate or buffer adolescent stressors (Collins & Russell 1991). Saetermoe et al (1999) refer to several research studies that demonstrate that communication problems within the family affect health and well-being. Aggressive behaviour in children emerged as strongly linked to parental conflict (Davis et al 1998). Lanz et al (1999) conducted a large study that revealed that children from separated or divorced families had more problems communicating with their parents and peer groups than adopted adolescents from intact families. Lanz et al (1999) concluded that male and female adolescent self-esteem is related to how well parents interact with each other. Brown et al’s (2007) research findings indicate that parents who talk supportively to their children about parental conflict promote healthy adaptation as the child feels more emotionally secure. According to Morrison & Anders (2001) there is little evidence to support the myth of adolescence as an emotional storm and challenge for parents. Most adolescents maintain close and supportive relations with their parents and ‘embody parental values rather than oppose them’ (Morrison & Anders 2001 p 69).

It would appear that adults are too quick to label the ‘terrible’ teenager (Fig. 10.5). If adults consider challenging behaviour in teenage years as the norm can young people be blamed for this? Adolescent transition to adulthood is synonymous with vulnerability and this may present challenges for those who work with young people. The philosophical belief underpinning work with children should be respect for their values, and human rights (Jennings & Hickson 2002). Health professionals need to remember that adolescent physical and emotional transitional stress can be exacerbated by traumatic experiences that impact on the young person’s maturity, beliefs, attitudes, health, behaviour and communication. Competent use of age- appropriate communication tools is essential.

|

| Fig. 10.5 Teenage sibling fun or fury? |

The value of play as a communication tool

Children often find it difficult to talk about their fears, frustrations and uncertainty to strangers. Play helps break down barriers with smaller children and enables them to express their feelings (Ellis 2000) and to reduce tension, anger, frustration, conflict and anxiety, which are mainly due to perceived loss of control and self-esteem (Haiait et al 2003). Techniques are used to enable children to project what they want using painting, puppets, drama and story telling (Fig. 10.6). Transferring ownership of emotions and feelings to a character seems to enable children to communicate powerful feelings, which would normally be too difficult to acknowledge due to embarrassment, loyalty or fear (Herpert & Harper-Dorton 2002). When a child is filling the gaps in story telling, caution must be taken in interpreting what is projected from reality and what is based on make believe.

Sometimes we see the world in fewer dimensions than children and all too often we reduce their imagination, creativity and energy into something that we feel comfortable with

(Carter 2002 p 83)

|

| Fig. 10.6 Expressing feelings through painting. |

Play is an effective means of preparing children for admission to hospital and for medical or surgical procedures. Demonstrating interventions on a doll or a teddy enables a child to take part and ask questions. The equipment becomes familiar and misconceptions are dispelled, which can reduce anxiety (Ellis 2000) by increasing their sense of control (Haiait et al 2003). It is within the guided framework of play that children are more likely to paint, write or talk about their emotions and experiences related to their illness, injury, treatment and hospitalisation (Haiait et al 2003) (Fig. 10.7). Play enables nurses, and other health professionals, to connect with child patients and to help them to feel at ease and secure, which is the basis of closeness and trust in a child’s relationship (Haiait et al 2003). To communicate effectively with children, taking account of their cognitive development, play must become an essential part of a nurse’s toolkit.

|

| Fig. 10.7 Painting and communication in hospital. |

Understanding health and illness

In the early 1980s, Bibace and Walsh, 1980 and Bibace and Walsh, 1981 outlined the stages of cognitive development and the relevance to healthcare professionals. It is not until the preoperational stage of development (2–6 years) that children attempt to understand why things happen, often assuming that illness is magically passed through close contact with another sick person. As cognitive development progresses (6–12 years), more concrete operational patterns of thinking enable children to use cause and effect as a basis of their understanding (if you go out in the cold without a coat you will get the cold). Children grasp that the illness is inside their body before they can comprehend how external factors can cause illness internally (Vacik et al 2001). In the formal operational stage, adolescents begin to understand body systems and how physical and psychological processes can result in illness (Vacik et al 2001).

Although Piaget mapped cognitive development into age groups, he repeatedly stressed the importance of sequence over rate. Bibace and Walsh, 1980 and Bibace and Walsh, 1981 point out that a child’s understanding is limited because memory, attention, bodily sensations and perception are still in the process of development (see Chapter 11).

Determining an individual child’s understanding and perception of illness is critical for effective communication to take place. In the last 30 years, there has been growing evidence of the need for adults to provide clarity when answering children’s questions about medical equipment, illness and treatment (Abbot 1990, Meijer, 2000, Ritchie, 1984 and Runeson, 2000, Tates & Meeuwesen 2002). If age-appropriate strategies are used, children can learn more about their illness, increasing compliance. Children as young as 4 years old have been taught how to effectively manage certain parts of their illness (Vacik et al 2001) (Fig. 10.8).

|

| Fig. 10.8 Two-year-old giving her dolly a nebuliser. |

McGrath & Huff (2001) conducted a study of preschool children playing with medical equipment. They discovered that most of them had a very ‘unsophisticated’ understanding of the use of the equipment but were keen to ask questions and learn. Two children whose older relatives had been in hospital made a good attempt at explaining surgery and the circulatory system:

… when the people are asleep. You get a very sharp knife and cut their tummy. That’s how they get things out

(McGrath & Huff 2001 p 458)

… actually you need blood inside you because it flows around our heart and if we didn’t have blood we’d die (McGrath & Huff 2001 p 458)

Worryingly, the children who did not engage in play had previous experience of hospital (self or sibling) and either did not want to talk about hospital or about a related, unpleasant experience. The ‘naive confidence’ demonstrated by the other children was replaced by ‘fearful descriptions’ (McGrath & Huff 2001 p 460). This would suggest that they had developed misconceptions due to lack of understanding of their hospital experience. All of the children in the study demonstrated a readiness to use their imagination to fill the gaps when information was lacking (McGrath & Huff 2001).

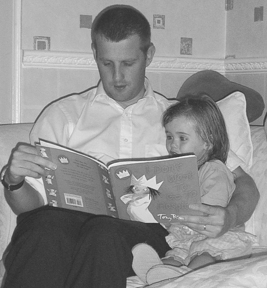

Effective communication with children can dispel misconceptions and anxieties, ultimately improving their healthcare experience. Nursing staff must explain to parents that preparing the child for admission to hospital promotes recovery. If a child cannot attend preadmission play clinics where special dolls, storybooks and videos are available, books and videos should be available for preparation at home (Fig. 10.9). However, such techniques may not be appropriate for use with older children (see also Chapter 5).

|

| Fig. 10.9 A father prepares his child at home for admission to hospital. |

Communicating with young people in a healthcare context

Bannister & Huntington (2002) highlight the importance of considering young people in local and strategic planning, delivery and evaluation of services. Children express valuable views with as much authenticity and meaning as could be expected from an adult group (Elliot & Watson 2000). Two studies (Elliot & Watson 2000, Tates et al 2002) highlight positive and negative aspects of interaction between health professionals and young people.

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practiceElliot and Watson (2000): 21 semi-structured group interviews involving over 200 children aged between 4 and 16 years on various aspects of health care and the services provided.

• Doctors tended to automatically address parents or other adult carers accompanying them regardless of the child’s age.

• Some doctors did not speak to them at all, even during an examination.

• Children doubted a doctor’s ability to find out what was wrong with them by asking only their parents who did not know all of their problems.

• When they were allowed to speak some doctors dismissed or trivialised their complaints.

• Doctors used language children could not understand.

• Doctors did not always keep their promises.

• Generally doctors were perceived as important people who had curative powers who were authoritarian and judgemental at times.

• Doctors had a negative image of older children, viewing younger children as small and sweet and not old enough to be trusted.

• Nurses listen more than doctors, are more approachable and perceived as less powerful.

• Children valued the opportunity to talk to a trusted knowledgeable person in confidence about matters they might not be able to discuss with parents and friends.

• Children wanted more information and confidential advice which is relevant for children and young adults.

Tates et al (2002): quantitative analysis of 106 videotaped interactions patterns of communication emerged during GP parent and child interviews.

• Parents generally viewed their child’s health as their responsibility so the interview was conducted as if the child was absent.

• Some GPs did take into account the child’s age and understanding (the child was asked what the problem was in only 35 out of 104 interviews).

• Some parents restricted child participation by interfering in GP–child interaction.

• Lack of participation on the child’s part was not due to lack of understanding.

• Only 5% of children were given information on diagnosis and treatment directly.

The research by Tates et al (2002) corroborates the concerns of the young people highlighted by Elliot & Watson (2000). It is clear that, although some GPs did attempt to consider the child’s understanding and engage the child in discussion, this was an exception rather than a rule. Mayall (1996 p 275) states that, from the literature, the child’s ‘position within medical encounters is doubly dependent on parental and medical staff behaviour’. Therefore, it is the responsibility of the adults in the interaction to provide a developmentally sensitive environment in which children are given the opportunity to be active participants in a healthcare context (Tates et al 2002).

www

www

www

wwwTake time to consider implications of Department of Health (2003) ‘Getting the Right Start: National Service Framework for Children: Standards for Hospital Services’. Pay particular attention to:

•Chapter 2 Standards for hospital services for children: 2.8–2.8; 2.21–2.23 Quality of Setting and Environment

•Chapter 3 Child centred Services: 3.10–3.35 Treating Children and Families with respect

• To what extent are the standards reflected in Scottish Executive (2007) Delivering a Healthy Future: Action Framework for Children and Young People’s Health in Scotland?

Identify key issues from both reports which underpin communicating with children and families in a healthcare context.

Children’s rights

In attempts to protect children it is easy to assume that they are incompetent and too foolish to know what is best for them:

The complexity of this issue can lead clinicians to take the easier option of assuming adults are competent and children are not

(Brook 2000 p 33)

The more pragmatic, balanced approach places the onus on the family and institutions to, on their behalf, ensure children’s well-being until they become adults, when they will be able to speak for themselves (Fulton 1996).

www

www

www

wwwCompare and contrast the Principles in the Declaration of the Rights of the Child 1959.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access