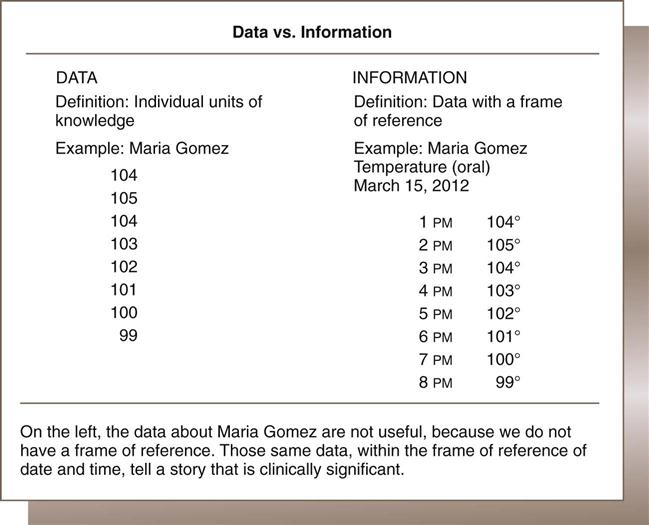

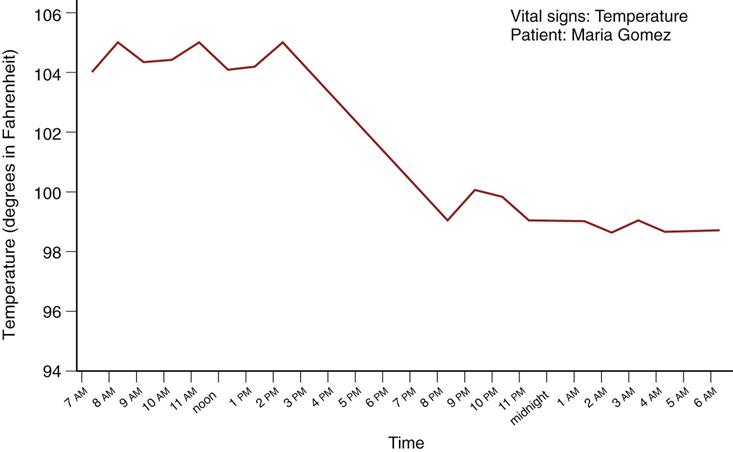

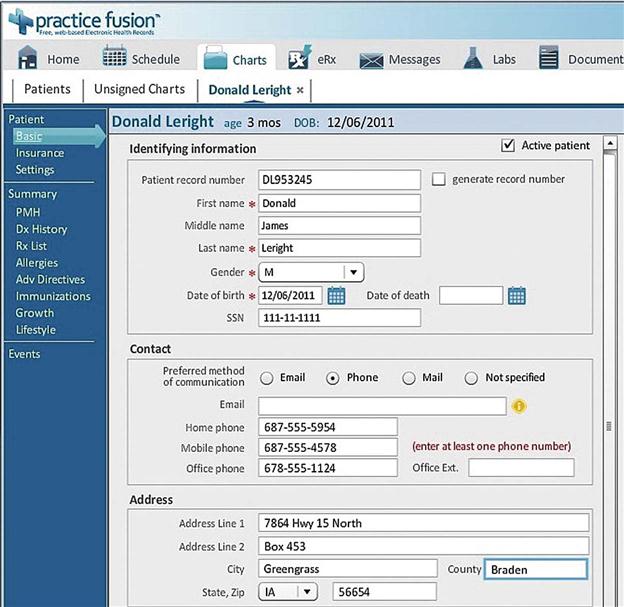

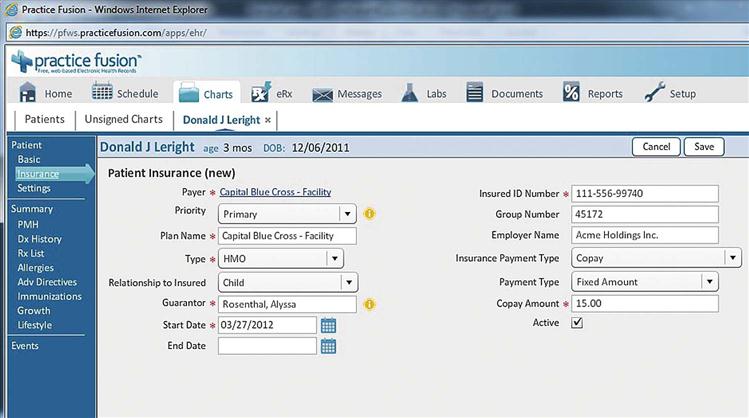

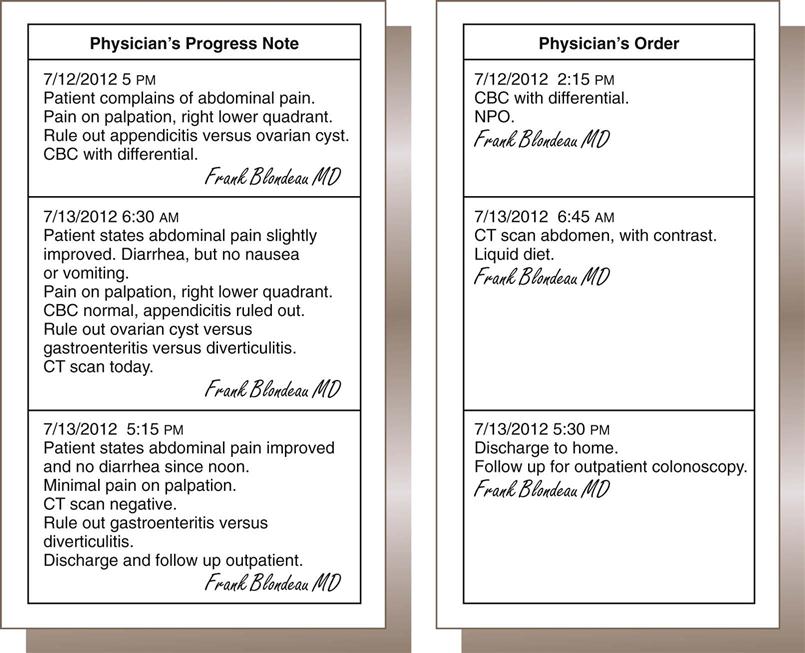

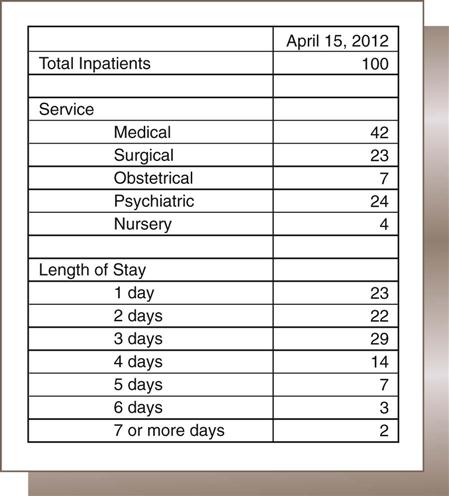

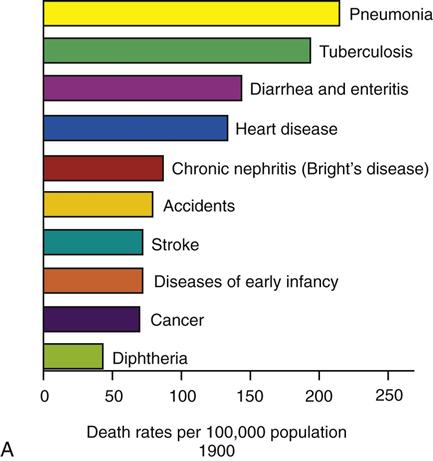

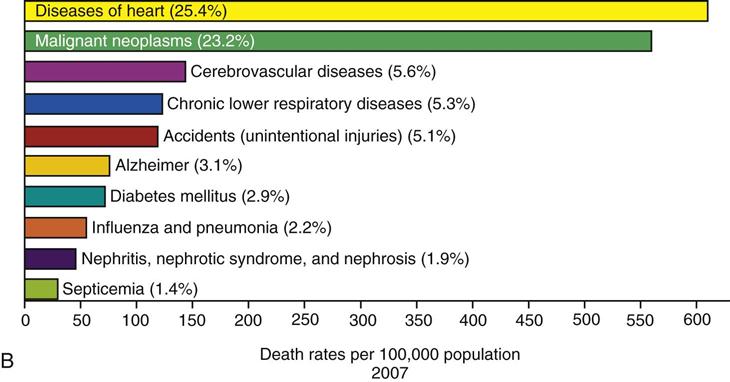

Nadinia Davis By the end of this chapter, the student should be able to: 1. Distinguish between data and information. 2. Define health and explain its relation to health data. 3. List and explain key data categories. 4. Distinguish among characters, fields, records, and files. 5. Describe how data are organized in a health record. 6. List and describe key data collection and quality issues. 7. Define the data sets used in health care and identify their applications and purposes. aggregate data assessment authentication Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) character clinical data computerized physician order entry (CPOE) data data accessibility data accuracy data analytics data collection devices data consistency data dictionary data set data validity database demographic data electronic health record electronic signature epidemiology field file financial data guarantor health data health information health record (medical record) information integrated record master forms file master patient index (MPI) Minimum Data Set (MDS 3.0) morbidity mortality National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) objective outcome Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) payer plan of treatment problem list problem-oriented record record rule out SOAP format socioeconomic data source-oriented record subjective symptom Uniform Bill (UB-04) Uniform Hospital Discharge Data Set (UHDDS) vital statistic Chapter 1 contained a discussion of various health care professionals and the settings in which they work. While caring for patients, health care workers listen to the patients and make observations. They record those observations, along with their evaluations and plans for further assessment and treatment. All of the assessment and treatment activities are further documented along with the outcome of these activities. This chapter focuses on the ways that health care workers record what they observe and what they do. It often surprises patients when health care workers record their observations on paper. Popular literature and cinema often present a futuristic view of health care delivery in which documentation is captured and saved in computers, which then magically analyze and diagnose the patient. Although the technology certainly exists and is used in some settings, its universal implementation has not arrived. Because the United States is making the transition from paper- to computer-based standards, both are addressed to the extent that is practical in this text. Some basic terminology will assist your understanding of the material in this chapter as well as the rest of the text. Although these terms may be meaningful in other ways, it is important to understand them in the context of health care. Health begins with the absence of disease. For the purposes of this discussion, consider a disease to be an abnormality caused by organic, environmental, or congenital problems. Therefore a person with no diseases is considered “healthy.” Suppose a person has no diseases but is very emotionally upset about events in his or her life: Is that person healthy? Not really. Long-term emotional upheaval can lead to a number of serious diseases. Consequently, emotional concerns detract from health. What about a child who does not get enough to eat but is currently free from disease? Won’t that child eventually deteriorate and become unhealthy over time? Of course. A person who is healthy is free of disease and is also free of outside physical, social, and other problems that could lead to a disease condition. Our knowledge about health comes from information we have analyzed, based on health care data. The primary purpose of this book is to discuss data in the health care setting; how data are organized, stored, and retrieved, and how one can create information from data. So it is important to understand that data are the building blocks of information that is used for many different purposes. Health information starts with data. Data are items, observations, or raw facts. A person can collect data without actually understanding it. For example, say there are 100 patients in Community Hospital today. What does that mean? Is that a lot of patients? How many patients should there be? So the number of patients in the hospital is not meaningful without understanding the context of the data collection. Similarly, other characteristics of hospital patients must be identified before the data are useful. The gender of the patients (male or female), the ages of the patients, and the types of services the patients are receiving are all important characteristics that would help explain the 100 patients. Clearly, information is needed. To interpret data—to make sense of the facts and use them—the data must be organized. The goal of organizing the data is to provide information. The terms data and information are often used synonymously, but they are not the same. “Get me the data” usually really means “get me useful information.” Data are the units of observation, and information is data that has been organized to make it useful. Figure 2-1 provides an organized report of the 100 patients that gives the user information. On the left in Figure 2-2 is a list of data pertaining to Maria Gomez. The user cannot tell what the data on the left signify until it is determined that they are her oral temperatures, taken at 1-hour intervals. Only then do the data become useful. In Figure 2-2, the temperatures are listed in chronological order. On the basis of these few observations, it is easy to see that Maria’s temperature is going down. If a nurse took Maria’s temperature every hour for 5 days, there would be more than 100 items of data. But even listing them in order would not be helpful: there would be too many numbers to process visually. Therefore the most useful information is often data organized into a picture, such as the graph shown in Figure 2-3. Here, we can see that Maria’s temperature was high in the morning, but returned to normal later in the evening and stayed there. The figure shows that the usefulness of data depends on their organization and presentation. These two examples show that data becomes information when it is organized and when it is presented in the proper context. Sometimes, a list is enough; other times, pictures are more helpful. Many types of data can be collected. Figure 2-2 is an example of health data. Health data are items in reference to an individual patient or a group of patients. We can list all of the diseases that a patient has (for continuing patient care) or all of the patients who have a certain disease (to start an audit, for example). The series of temperatures collected and reported from Maria Gomez in Figures 2-2 and 2-3 is the health data from one patient. Similarly, one can obtain vast quantities of data on individual patients or groups of patients. Imagine a list of 10,000 patients and their diseases. Are these useful data? What could be done with these data? Unless one is prepared to organize it, the list is not very informative. However, a list of the top 10 most common diseases of 10,000 residents in a particular location would be quite useful. This type of information is published frequently. For example, Figure 2-4 shows the top 10 causes of death in the United States in 1900 and 2007. Certainly, a list of the top 500 causes of death would not have been as useful. Health information is health data that have been organized. In Figure 2-3, the temperatures gathered become health information when the user understands that those temperatures are for one patient at certain times of the day. Health data related to 10,000 residents become health information when the data are organized in a way that is meaningful to the reader. Listing the top 10 diseases of a city’s residents is useful health information. This is information that physicians can use to make decisions. In Figure 2-4, for example, tuberculosis and diarrhea/enteritis are no longer on the list of the top ten causes of death (mortality) in the United States. Mortality data are a vital statistic captured through the death certificate filing process, discussed in detail in Chapter 10. Births and marriages are also vital statistics. Morbidity, or disease process, data are captured through the reporting of patient-specific data from various types of facilities. Upon study, one finds that the development of antibiotics and vaccines and improvements in sanitation have significantly reduced the number of deaths caused by these conditions. The graphs in Figure 2-4 present interesting information that helps us ask questions that lead to more information. The study of these types of health trends or patterns is called epidemiology. Health information is a broad category. It may refer to the organized data that have been collected about an individual patient, or it can be the summary of information about that patient’s entire experience with his or her physician. Health information can also be summary information about all of the patients that a physician has seen (also called aggregate data). Furthermore, health information managers can take all of the available information about patients in a particular geographical area and make broad statements on the basis of this array of information (public health information). The process of examining the data and exploring them to create information is called data analytics. Health information therefore encompasses the organization of a limitless array of possible data items and combinations of data items. It can range from data about the care of an individual patient to information about the health trends of an entire nation. The primary purpose of recording data is communication, which is necessary for a variety of reasons. For example, a medical assistant may take a patient’s vital signs for the physician’s reference. The physician records her observations so that she can measure the patient’s progress at a later date. Thus recording health data is an important way for health care professionals to communicate and facilitate patient care. Beyond patient care, there are many other uses of health data. Hospital administrators use health data in order to make decisions about what services to offer and how best to serve the communities in which they are located. Lawyers use health data to demonstrate the extent of injuries suffered by a client. Payers, such as insurance companies and Medicare, use health data to determine reimbursement to providers. Government agencies, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) use health data to monitor diseases. The CDC is a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Within the CDC is the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), which collects and analyzes mortality and other vital statistics. Box 2-1 shows a complete list of the DHHS’s Operating Divisions. These government agencies are just two of the many users of data that are collected and reported by providers. Chapter 7 discusses the use of health data for reimbursement. Chapter 10 discusses the statistical analysis of health data for many different purposes. Chapter 11 discusses some administrative uses of health data. Health data that are collected in a consistent, systematic process are most easily organized into information. There are four broad categories into which health data are collected: demographic, socioeconomic, financial, and clinical. Demographic data identify the patient. Name, address, age, and gender are examples of demographic data. The physician needs the patient’s name and address to send the patient correspondence, follow-up notices, or a bill. Other necessary data include the home phone number, place of employment, work telephone number, race, ethnicity, and Social Security number. The physician needs these data both to contact the patient and to distinguish one patient from another. Figure 2-5 shows demographic data collected for a new patient. Demographic data helps the physician answer questions such as: How old are my patients? Where do my patients live? Another type of data about a patient that a physician collects is socioeconomic data. These personal data include the patient’s marital status, education, and personal habits. Many students ask why the patient’s socioeconomic situation is relevant to health care. One of the reasons that such data are important is that the diagnosis of many illnesses, and sometimes their treatment, depends on the doctor’s understanding of the patient’s personal situation. A list of socioeconomic data is presented in Box 2-2. A patient with asthma who smokes will likely be advised by his or her physician to quit smoking. This is an example of a personal habit that directly affects a disease condition. In addition, the socioeconomic situation or personal life of a patient sometimes dictates whether the patient will be compliant with a medication regimen or even whether he or she is able to obtain treatment. For example, if an older patient has just undergone a hip replacement, sending that patient home to a third-story walk-up apartment might be a problem. It will be very difficult for the patient to get in and out of the apartment and certainly very difficult for the patient to leave the apartment for therapy, particularly if there is no caregiver at home. Treatment at home might be needed as well as assistance with grocery shopping. Another possibility is to keep the patient in the hospital until the patient is comfortable with stairs. Therefore understanding a patient’s personal life and living situation is important to the planning of how to care for the patient. Sometimes the knowledge that a patient travels widely can lead a physician to suspect an illness that he or she would not consider if the patient never traveled. Travel in certain areas of the world could have caused exposure to diseases that are uncommon in his or her native area. Thus a patient’s complaint of abdominal pain could lead the physician to suspect a parasite (an organism that may have been swallowed and is living in the intestines), whereas ordinarily the physician would consider only bacterial or viral causes. When requesting services from any health care provider, one expects at some point that payment of some sort will be required. The physician requests information about the party responsible for paying the bill. This information makes up the financial data. Financial data relate to the payment of the bill for services rendered. The party (person or organization) from whom the provider is expecting payment for services rendered is called the payer. The payer is frequently an insurance company. It may also be a government agency, such as Medicare or Medicaid. Many patients have more than one payer. The primary payer is billed first for payment. A secondary payer is approached for any amount that the primary payer did not remit, and so on. For example, patients who are covered by Medicare may have supplemental or secondary insurance with a different payer. The physician first sends the bill to Medicare. Any amount that Medicare does not pay is then billed to the secondary payer. The patient may also have some responsibility for part of the payment. Ultimately, the patient is financially responsible for payment of services that he or she has received. If the patient is a dependent, a person other than the patient may be ultimately responsible for the bill. The person who is ultimately responsible for paying the bill is called the guarantor. For example, if a child goes to the physician’s office for treatment, the child, as a dependent, cannot be held responsible for the invoice. Therefore the parent or legal guardian is responsible for payment and is the guarantor. Figure 2-6 shows financial data required by a health care provider. Clinical data are probably the easiest to understand and relate to the health care field. Clinical data comprise all of the data that have been recorded about the patient’s health, including the physician’s conclusion about the patient’s condition (diagnosis) and what plan or treatment (procedures) will be recommended. The following example illustrates clinical data. The patient presents in the physician’s office for pain in the abdomen. The physician knows that pain in the abdomen can be caused by a variety of conditions. The pain is merely a symptom, a description of what the patient feels or is experiencing. Other symptoms may include nausea, dizziness, and headache. The physician orders tests and performs a physical examination to determine which of those conditions is responsible for the abdominal pain. Some of these tests include radiographs and blood tests. Ultimately, the physician may conclude that the abdominal pain is caused by an inflamed appendix, or appendicitis. Appendicitis is the diagnosis, and the blood test and physical examination are the procedures. The physician records both the findings of the examination and the results of the tests in the patient’s record. Clinical data constitute the bulk of any patient’s record. All of the previous data that have been discussed—demographic, socioeconomic, and financial—can usually be contained in one or two pages in the front of a patient’s health record. The rest of the record is the clinical data. Box 2-3 lists examples of clinical data. A logical thought process supports the medical evaluation process, or development of a medical diagnosis. Data are collected in one of four specific categories: the patient’s subjective view, the physician’s objective view, the physician’s opinion or assessment, and the care plan. This method of recording observations or clinical evaluations is called the SOAP format: subjective, objective, assessment, and plan. Although physicians may not always follow this format exactly, they record their thoughts in this general manner. Table 2-1 lists the elements of a medical evaluation. TABLE 2-1 ELEMENTS OF MEDICAL EVALUATION (SOAP) In conducting the evaluation, the physician collects data sufficient to develop a medical diagnosis. Initially, the data may support several different diagnoses. The physician continues to collect and analyze data until a specific diagnosis can be determined. For example, chest pain and shortness of breath can be symptoms of many conditions, including myocardial infarction (heart attack), congestive heart failure (a heart pumping problem that causes a buildup of fluid), and pneumonia (inflammation of the lungs). The physician examines the patient and orders enough tests to conclude which diagnosis (or diagnoses) applies in each individual case. The physician begins the medical evaluation process by asking the patient about the medical problem and the symptoms that he or she is experiencing. The patient’s description of the problem, in his or her own words, is the subjective or history portion of the evaluation process. For example, the patient may have stomach pain. The patient may describe this as “abdominal pain,” “pain in the belly,” or “pain in the stomach.” The physician’s task is to narrow the patient’s description through questioning. For instance, the patient can be assisted to identify the pain as a sharp, stabbing pain in the lower right portion of the abdomen. The physician also asks when the pain began, whether it is continuous or intermittent, and whether there are any other symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting. The physician will record the patient’s description in the patient’s own words. Once the physician has obtained and recorded the patient’s subjective impressions about the medical problem, the physician must look at the patient objectively. The physician conducts a physical examination, exploring the places where the stomach pain may be located. The patient says his or her stomach hurts, but the physician records that the patient has “tenderness on palpation in the right lower quadrant.” Tenderness on palpation in the right lower quadrant is a classic indication of appendicitis. Other possible diagnoses (also called differential diagnoses) are ovarian cyst and a variety of intestinal disorders, such as diverticulitis (inflammation of the intestines). The physician’s objective notation is the specific anatomical location of the pain, vital signs, and the results of any laboratory tests that the physician ordered. The physician orders tests to confirm a likely diagnosis or to rule out, or eliminate, a possible diagnosis. In this example, the physician is looking for an elevation of the white blood cell (WBC) count, which indicates the presence of an infection. The physician may rule out differential diagnoses such as appendicitis if the WBC count is normal. Additional tests, such as an abdominal ultrasound, might be ordered if the blood test results are negative or inconclusive. Once the physician has obtained the patient’s subjective view and has conducted an objective medical evaluation, he or she develops an assessment. The assessment is a description of what the physician thinks is wrong with the patient: the diagnosis or possible (provisional) diagnoses. If there are multiple possible diagnoses, the physician would record “possible appendicitis versus ovarian cyst” or “rule out appendicitis, rule out ovarian cyst.” The phrase “rule out” means that the diagnosis is still under investigation. “Ruled out” means that the diagnosis has been eliminated as a possibility. In this abdominal pain example, if the physician has eliminated the possibility of an ovarian cyst and has concluded that the patient has appendicitis, the documentation would read: “appendicitis, ovarian cyst ruled out.” Once the physician has assessed what is wrong with the patient, he or she writes a plan of treatment. The plan may be for treatment or for further evaluation, particularly if the assessment includes several possible diagnoses. Figure 2-7 illustrates the pattern of data collection. Other clinical personnel also record their observations but not necessarily in the SOAP format. Many nursing evaluations are recorded through the use of graphs or on preprinted forms. Graphs or preprinted forms are also used for clinical evaluations in physical therapy, respiratory therapy, and anesthesia records; also, some surgical records and many maternity and neonatal records use preprinted or graphical forms. It should be noted that an increasingly important component of the medical decision-making process is the outcome: the result of the plan. Insurance companies may use the history and trending of outcomes to determine which health care providers will be included in their networks. In an acute care (hospital) record, the outcome of the admission is captured in several places: the diagnoses and procedures, the discharge disposition (e.g., home, nursing home, expired), and the physician’s overall explanation of the stay in the discharge summary. Often, the patient is not fully recovered when discharged, and additional follow-up is required. Therefore some outcomes are inferred. For example, if the patient is discharged on Monday and readmitted on Thursday for the same diagnosis, it could be inferred that the outcome of the plan during the first admission was not successful. The reasons for unsuccessful outcomes are not necessarily the fault of the attending physician or the facility in which the patient was treated. The patient may not have complied with discharge instructions, for example. Nevertheless, the readmission is attributed to both the attending physician and the facility in the reporting of such data. One example of the shifting emphasis on outcomes and follow-up is the Medical Home model of primary care. Medical Home refers to the proactive coordination of patient care by the primary care physician. The Medical Home model requires coordination and collaboration among all caregivers in order to ensure that the patient’s transition from one setting to another is seamless and is supported by the data collected in the prior settings. In this manner, the primary care physician would be informed concurrently of the patient’s inpatient treatment and discharge instructions so that follow-up would occur promptly, ensuring that the patient understood and was following discharge instructions, potentially preventing unnecessary readmission.

Collecting Health Care Data

Chapter Objectives

Vocabulary

Basic Concepts

Health

Data

Information

Health Data

Health Information

Key Data Categories

Demographic Data

Socioeconomic Data

Financial Data

Clinical Data

Medical Decision Making

DATA ELEMENT

EXPLANATION

Subjective

The patient’s report of symptoms or problems

Objective

The physician’s observations, including evaluation of diagnostic test results

Assessment

The physician’s opinion as to the diagnosis or possible diagnoses

Plan

Treatment or further diagnostic evaluation

Subjective

Objective

Assessment

Plan

Outcome

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Collecting Health Care Data

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access