Resources

A collection of resources, often referred to as the depression “toolkit,” was assembled for use in the HRC Depression Support Service.

Depression screening

During the initial rollout of the Depression Support Service, all of the HRC residents were being assessed for depression via the MDS, administered by nursing staff quarterly. While there was reason to believe that the MDS depression rating scale was not the optimal instrument for identifying depression (Anderson et al. 2003), staffing constraints did not permit administering to all residents one of the preferred screening instruments such as the Geriatric Depression Scale or the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) (Snowden et al. 2009). This issue was resolved with incorporation of the PHQ-9 in the recently released MDS 3.0 (Saliba & Buchanan 2008).

Clinician education modules

Three 30-minute presentations were created and presented to the medical staff during regularly scheduled medical staff meetings. Topics covered included: barriers to identifying depression, updates on late-life depression psychopharmacology, and an introduction to the collaborative care model. Minutes of these meetings were distributed to all of the medical staff with information on how to access the education modules.

Quick reference for antidepressant medications (Table 25.1)

A double-sided laminated guide was provided to each of the geriatricians and posted on each of the nursing units. The reference was adapted and updated from a similar resource developed by the MacArthur Foundation (MacArthur Initiative on Depression and Primary Care).

Table 25.1 Quick Reference for Antidepressants

Psychotherapy

Most depression toolkits include references and forms for initiating and continuing short-term psychotherapy. After relatively brief training, depression care managers without advance degrees can provide effective Problem Solving Therapy or Behavior Activation Therapy (Arean et al. 2008). Because the first depression care manager in the HRC Depression Support Service was a PhD psychologist with experience in short-term therapy, she did not undergo re-training in one of these modalities. With expansion of the program (see below), the next depression care manager, a nurse practitioner without specialized training in psychiatry, underwent live IMPACT training at the University of Washington.

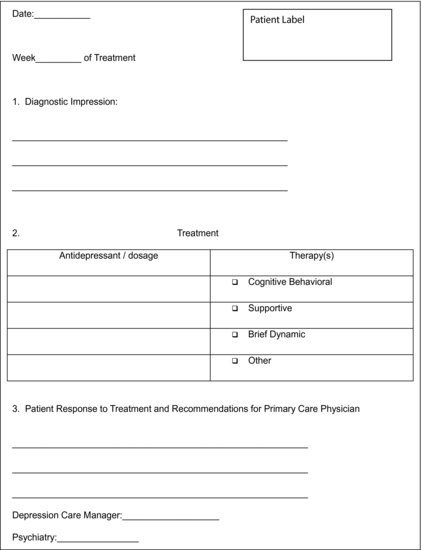

Communication form (Table 25.2)

This form was completed by the depression care manager and the psychiatrist during supervisory sessions and was the primary form of communication between the Depression Support Service and the primary care team. The form was reviewed with other clinical documents (for example laboratory results, consultation reports) by the primary care team during routine rounds. The primary care team had the option of contacting the depression care manager or psychiatrist directly with additional questions.

Table 25.2 Depression Support Service Communication Form

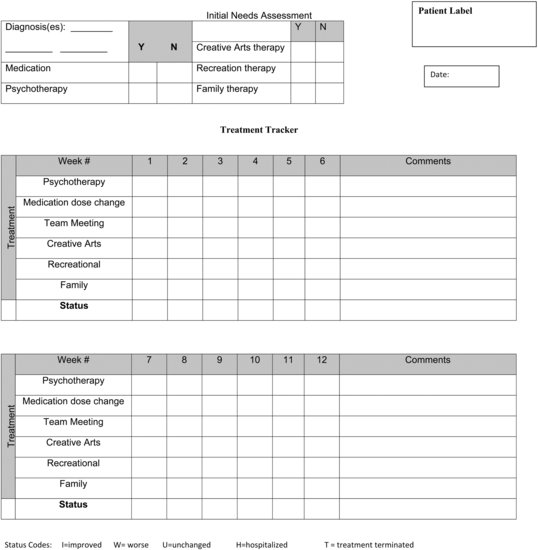

Depression care manager tracking form (Figure 25.2)

The depression care manager initiated a tracking form for each resident entered into the Depression Support Service. The form assisted the care manager and supervising psychiatrist in tracking the primary care team’s response to the care manager’s recommendations and tracking the resident’s response to treatment.

Measurement

Process and outcome measures were identified to quantify the results of this pilot phase of the Depression Support Service. Process measures were selected to measure the geriatricians’ acceptance of the new program and included attendance at the education modules, orders entered requesting the Depression Support Service, and change in orders requesting traditional psychiatric consultation for depression. Outcome measures included changes in residents’ scores on the MDS Depression Rating Scale, clinicians’ completion of a knowledge and attitude survey on late-life depression, and physician productivity as measured by billing before and after the rollout of the Depression Support Service. For the purposes of this pilot phase, the nursing units caring for residents with end-stage dementia were excluded from measurement, limiting the study population to 6 geriatricians and 252 residents.

The HRC experience, facilitators and barriers

Rollout

The Depression Support Service was introduced to the medical staff with the first education module at a regularly scheduled meeting. The physician-in-chief’s championing of the new service and willingness to include the education modules on the agendas of the mandatory medical staff meetings were strong facilitators of the rollout process. Attendance for the medical staff meetings at which the education modules were presented averaged 60%, comparable to usual attendance. Completion of the knowledge and attitude survey by the geriatricians was 100%.

Referrals to the depression support service

During the initial 12-month pilot phase, the Depression Support Service received 72 referrals. An order for the new service was added to the menu of the recently adopted electronic order entry system, which facilitated clinicians’ access to the service. Referrals for consultation from the psychiatrist for depression showed a corresponding decrease for these units, declining from 96 over the course of the previous year to 18 during the support service pilot phase. Review of the requests for traditional psychiatric consultation revealed that a number were because of family request or extenuating circumstances (for example, history of bipolar disorder).

Effect on depression

MDS Depression Rating Scale scores were calculated for all residents on the units studied for the quarter prior to the rollout of the Depression Support Service and the quarter one year into service implementation. For the six units combined, there was a trend toward improvement of depression scores. There was significant improvement in depression scores on one of the units.

Impact on the geriatricians

Medical staff participation in the depression knowledge survey was 100% for both the pre- and post-tests. Mean scores on the primary care provider survey items of knowledge of depression and on confidence in treating depression did not change significantly during the project period, however the sample size was insufficient to rule out a type II error. A qualitative review of the surveys indicated that: (1) primary care providers believed it was their responsibility to manage depression (100% response); (2) primary care providers had accurate beliefs about how antidepressants work (72%); and (3) providers felt at least “mostly” confident about treating depression (100%). High pre-implementation scores indicated a high baseline level of knowledge about geriatric depression, and the lack of change in the scores indicated a ceiling effect. The primary care physicians in this project were all board certified in geriatrics, which may in part account for their high baseline knowledge of geriatric depression. Being members of a closed medical staff with frequent contact with the psychiatrists may also have contributed to their knowledge and confidence in depression management.

Provider productivity was measured by Medicare Resource Value Units (RVUs) before and after implementation of the Depression Support Service. Total RVUs for the six clinicians decreased from 782 to 637 between the two time periods, but was not statistically significant. This trend toward a decrease in RVUs for the physicians participating in the project was unexpected. However, coincident with the implementation of the Depression Support Service the hospital implemented both a new electronic medical record and a new voice recognition software system for dictating progress notes. Subjective reports from the physicians were that the introduction of both these technologies had significant short-term impact on their productivity. As described previously, more sophisticated studies of collaborative care programs like IMPACT have demonstrated cost effectiveness.

Dissemination: A statewide project

Researchers at Masspro, a healthcare performance improvement organization which serves as the federal subcontractor for the Quality Improvement Organization within Massachusetts, sought ways to decrease the prescription of medications considered to be potentially inappropriate for older patients. Improving the diagnosis and treatment of late-life depression can decrease prescribing of anti-anxiety and antipsychotic medications known to be associated with increased morbidity and mortality in older patients. Masspro has teamed up with HRC staff involved with the HRC Depression Support Service in order to disseminate this model to community health centers across the state. In addition to live presentations, the team has produced 10 informational webinars describing in detail the collaborative care approach to treating late-life depression.

Future directions: An expanding role for collaborative care depression treatment in the HSL system

As described at the outset of this chapter, the HSL system of medical care and housing has continued to grow. Accompanying this growth has been an increased demand for psychiatric services, making the Depression Support Service more relevant than ever. The positive HRC pilot results, in combination with the results of larger studies described previously, have led to acceptance of the model by both hospital administration and the department of medicine and a commitment to expand the service. Financial support from both HSL and a technical implementation package awarded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Carter Center, and the University of Washington allowed for a medical nurse practitioner to attend an IMPACT training and begin depression care manager work at HSL’s community elder housing sites. As illustrated by the following case, expansion into the outpatient arena has brought new challenges.

Case study

Ms. R an 82-year-old widowed woman, and has resided at the HSL senior housing, Center Communities of Brookline, for three years. She was insured by a Medicare Advantage HMO and became one of the first clients of the HSL outpatient Depression Support Service when her primary care physician referred her for depressed affect, social isolation, and insomnia. She was visited by the nurse practitioner depression care manager and was determined to be an appropriate referral for collaborative care treatment of her depression. Her initial PHQ-9 score was 11/27, consistent with mild depression. A chief psychosocial precipitant to the depression was Ms. R’s husband having been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Starting with the first visit, Ms. R began a course of Problem Solving Psychotherapy and a low dose of antidepressant medication. Ms. R began to report subjective benefit from the visits and her PHQ 9 score dropped to 9 after two visits.

Prior to the third visit, Ms. R called the depression care manger to inform her that she would be reducing her visits to monthly. On questioning, Ms. R confessed that the reason behind the change was the HMO mandated $25 co-pay per session, which was prohibitive on her fixed income. Discussions ensued in the business office about the legality and sustainability of waiving co-payments in these instances, with the conclusion that the co-payments would need to be enforced. At follow-up one month later, Ms. R had not completed her prescribed Problem Solving homework for the session and had neglected to refill her antidepressant medication prescription. Her PHQ 9 score had increased to 12. The depression care manager called Ms. R’s primary care geriatrician to share her concerns about worsening depression.

In seeking to expand the Depression Support Service, HSL has had to address issues faced by many organizations which seek to sustain a successful collaborative care service after completion of a grant (Bachman et al. 2006; Belnap et al. 2006). The most frequently encountered issue is funding for the care manager position. HSL’s initial care managers were a PhD psychologist and a nurse practitioner. Advantages of utilizing an advance practice clinician in this role included: (1) prior psychiatric training; (2) ability to at least partially support the position by billing for psychotherapy services when appropriate. Disadvantages of filling additional depression care manager positions with advance practice staff include: (1) lack of availability of advance practice clinicians with geriatrics expertise or interest; (2) higher cost of advance practice clinicians’ salaries; and (3) as illustrated by the case above, monetary constraints placed on the patient when the depression care manager bills insurance to help support the position.

Future directions: Support of collaborative care for late-life depression on a national level

Depressive illness is a major public health concern and has been identified by the World Health Organization as one of the leading causes of disability (Pan American Health Organization). In the United States alone, direct and indirect costs of depression are estimated at $83 billion (Greenberg et al. 2003). In patients with physical illness, co-morbid depression increases healthcare service utilization by as much as 50% (Luber et al. 2001). As the portion of the elderly population continues to increase, the number of geropsychiatric specialists will not keep pace (Bartels 2003). Although collaborative care programs have been proven both clinically efficacious and cost effective for the health care systems responsible for medical and psychiatric care, significant barriers remain which have prevented more widespread dissemination. As described above, foremost among these barriers has been finding funding for the depression care manager position, a key component of the collaborative care model. Recent developments offer hope that coalitions on a statewide level may provide means for overcoming these barriers.

Depression Improvement Across Minnesota, Offering a New Direction (DIAMOND) is a project involving a unique collaboration between medical groups, commercial health plans, and the Minnesota Department of Human Services (Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement 2008). Also based on the IMPACT model of collaborative care treatment of depression, the program utilizes depression care managers and a depression toolkit as described in this chapter. Unique to the DIAMOND program is a new payment system whereby health plans pay a “care management fee” to participating medical groups to cover the expenses of the depression care manager and supervising psychiatrist. Forty-five clinics have been enrolled to date with another 40 scheduled to be enrolled by the end of 2010. DIAMOND’s results, which are currently being studied under an NIMH grant, may encourage similar collaborations in other states.

Collaborations between medical groups and payers are also occurring in many states to support the development of the Patient-Centered Medical Home model of primary care. The Medical Home model, a hallmark of which is coordination of care, is ideally suited to support collaborative care treatment of depression. The Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC), a national coalition which includes employers, primary care societies, national health plans, and patient groups, lists 17 states with one or more Patient-Centered Medical Home pilots underway (PCPCC 2008). Recognizing the value of such statewide collaboration, the Departments of Health and Human Services and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced in June 2010 that they would support up to six state demonstration projects of Multi-Payer Advanced Primary Care (MPAPC) practices (CMS 2009).

Barriers to implementation of effective depression treatment for elders can also be addressed by national health care policy which supports the dissemination of this successful intervention. As highlighted by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, “Retooling for an Aging America,” fee-for-service Medicare, in which the majority of Medicare recipients are enrolled, discourages adoption of collaborative care models because: (1) Statutorily established benefit categories do not cover reimbursement for many of the services provided by the collaborative care model; and (2) Nurses and social workers, ideally suited for the roll of depression care managers, do not qualify for reimbursement (IOM 2008).

Summary

This chapter describes the introduction of a program for coordinated care of depression in the long-term care setting using a collaborative care model adapted from IMPACT. The program’s successful pilot has led to institutional support of the expansion of the program to other practice sites in the organization as well as to support from the state’s Medicare Quality Improvement contractor to disseminate the model to community health centers across the state. Barriers to adoption of the collaborative care model are chiefly around funding for the depression care manager and supervising psychiatrist roles. Research is currently underway to determine if promising statewide collaborations between medical practices and payers will overcome these barriers and lead to nationwide implementation of this effective means for treating depression.

References

Anderson, R.L., Buckwalter, K.C., Buchanan, R.J., et al. (2003) Validity and reliability of the Minimum Data Set Depression Rating Scale (MDSDRS) for older adults in nursing homes. Age and Ageing, 32, 435–438.

Arean, P., Hegel, M., Vannoy, S., et al. (2008) The effectiveness of problem solving therapy for older primary care patients with depression: results from the IMPACT project. The Gerontologist, 48, 311–323.

Bachman, J., Pincus, H.A., Houtsinger, J.K., et al. (2006) Funding mechanisms for depression care management: opportunities and challenges. General Hospital Psychiatry, 28, 278–288.

Bartels, S.J. (2003) Improving the system of care for older adults with mental illness in the United States. Findings and recommendations for the President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11, 486–496.

Belnap, B.H., Kuebler, J., Upshur, C., et al. (2006) Challenges of implementing depression care management in the primary care setting. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 33(1), 65–75.

Bush, D.E., Ziegeistein, R.C., Tayback, M., et al. (2001) Even minimal symptoms of depression increase mortality risk after acute myocardial infarction. American Journal of Cardiology, 88, 337–341.

Byers, A.L., Yaffe, K., Covinsky, K.E., et al. (2010) High occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders among older adults: The National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67, 489–496.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2009) Multi-payer Advanced Primary Care Practice (MAPCP) Demonstration Fact Sheet. Retrieved from http://www.cms.hhs.gov/DemoProjectsEvalRpts/MD/itemdetail.asp?itemID=CMS1230016.

Clever, S.L., Ford, D.E., Rubenstein, L.V., et al. (2006) Primary care patients’ involvement in decision-making is associated with improvement in depression. Medical Care, 44, 398–405.

Conwell, Y., Lyness, J.M., & Duberstein, P. (2000) Completed suicide among older patients in primary care practices: a controlled study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(1): 23–29.

Gilbody, S., Bower, P., Fletcher, J., et al. (2006). Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 2314–2320.

Greenberg, P.E., Kessler, R.C., Birnbaum, H.G., et al. (2003) The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64, 1465–1475.

Gum, A.M., Arean, P.A., Hunkeler, E., et al. (2006) Depression treatment preferences in older primary care patients. The Gerontologist, 46(1), 14–22.

Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. (2008) Depression Improvement Across Minnesota, Offering a New Direction. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, Minneapolis, MN. Retrieved from http://www.icis.org/health_care_redesign/diamond_35953/.

Institute of Medicine on the Future of Health Care Workforce for Older Americans. (2008) Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

Katon, W.J., Schoenbaum, M., Fan, M., et al. (2005) Cost-effectiveness of improving primary care treatment of late-life depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 1313–1320.

Luber, M.P., Meyers, B.S., Williams-Russo, P.G., et al. (2001) Depression and service utilization in elderly primary care patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 9, 562–571.

MacArthur Initiative on Depression and Primary Care. Resources for Clinicians. Retrieved from http://www.depression-primarycare.org/clinicians/toolkits.

Oxman, T.E., Dietrich, A.J., & Schulberg, H.C. (2003) The depression care manager and mental health specialist as collaborators within primary care. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11, 507–516.

Palmer, S.C., & Coyne, J.C. (2003) Screening for depression in medical care: pitfalls, alternatives, and revised priorities. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 54, 279–287.

Pan American Health Organization. 144th Session of the Executive Committee, Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization. Retrieved from www.http://new.paho.org.

Parmelee, P.A., Katz, I.R., & Lawton, M.P. (1992) Incidence of depression in long-term care settings. Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 47, M189–196.

Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. (2008) Patient Centered Medical Home: Building Evidence and Momentum. Retrieved from http://www.pcpcc.net/content/pcpcc_pilot_report.pdf.

Proctor, E.K., Hasche, L., Morrow-Howell, N., et al. (2008) Perceptions about competing psychosocial problems and treatment priorities among older adults with depression. Psychiatric Services, 59, 670–675.

Raue, P.J., Schulberg, H.C., Heo, M., et al. (2009) Patient’s depression treatment preferences and initiation, adherence, and outcome: a randomized primary care study. Psychiatric Services, 60, 337–343.

Saliba, D., & Buchanan, J. (2008) Development and Validation of a Revised Nursing Home Assessment Tool: MDS 3.0. Retrieved from http://www.cms.hhs.gov/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/MDS30FinalReport.pdf.

Schade, C.P., Jones, E.R., & Wittlin, B.J. (1998) A ten-year review of the validity and clinical utility of depression screening. Psychiatric Services, 49, 55–61.

Snowden, M.B., Steinman, L., Frederick, J., et al. (2009) Screening for depression in older adults: recommended instruments and consideration for community-based practice. Clinical Geriatrics, 17(9), 26–31.

U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. (2002) Screening for depression: recommendations and rationale. Annals of Internal Medicine, 136, 760–764.

Unutzer, J., Daton, W., Callahan, C.M., et al. (2002) Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized control trial. Journal of the American Management Association, 288, 2836–2846.

Ziffra, M.S., & Friedman, R.S. (2006) To screen or not to screen: is that the question? Improving the outcomes of depression in primary care. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management, 13, 562–571.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree