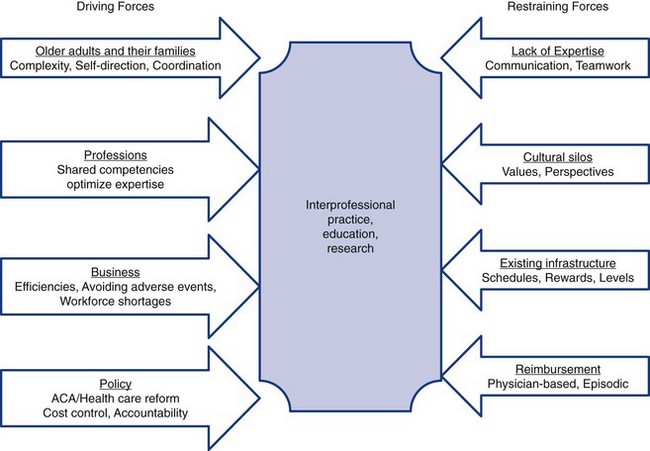

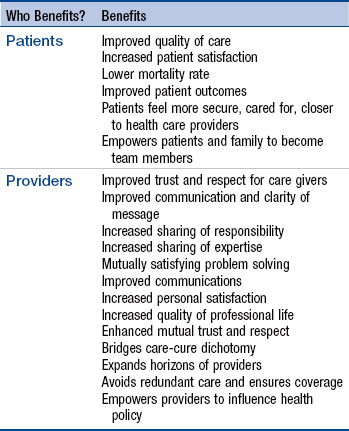

Chapter 12 Characteristics of Effective Collaboration Clinical Competence and Accountability Interpersonal Competence and Effective Communication Recognizing and Valuing Diverse, Complementary Culture, Knowledge, and Skills Impact of Collaboration on Patients and Clinicians Context of Collaboration in Contemporary Health Care Processes Associated with Effective Collaboration Strategies for Successful Collaboration The collaboration competency is important in that it is fundamental to successful APN practice. The presence or absence of collaborative relationships affects patient care, including the cost and quality of care. Patients assume that their health care providers communicate and collaborate effectively; thus, patient dissatisfaction with care, unsatisfactory clinical outcomes, and clinician frustration can often be traced to a failure to collaborate with other members of the health care team. Collaboration depends on clinical and interpersonal expertise and an understanding of factors that can promote or impede efforts to establish collegial relationships. The primary focus of this chapter is on collaboration between and among individuals and work groups within organizations and across larger health care delivery systems. Our goal in this chapter is to define collaboration and make more explicit the values, behaviors, structures, and processes that facilitate effective collaboration. Furthermore, the current trends in health care promulgated by the IOM Futures of Nursing report (2011) and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2011) and recent education initiatives toward a rebirth of interprofessional collaboration will be described. Some background on our definition of collaboration is warranted. When we began writing about collaboration, extant definitions of collaboration were inadequate to describe the process we experienced as clinicians (Hanson & Spross, 1996, 2000; Spross, 1989). The term collaboration is often associated with teamwork and partnership. The description of collaboration in the American Nurses Association’s (ANA’s) Social Policy Statement (ANA, 2003) and the American College of Nurse-Midwives’ (ACNMs’) collaboration statement (ACNM, 2011; see Chapters 7 and 17) have informed our conceptualization and definition of collaboration. The ANA recognized that the boundaries of each health care professional’s practice change and that high-quality care depends on a common focus, recognition of each other’s expertise, appreciation for the skills and knowledge shared across disciplines, and the collegial exchange of ideas and knowledge. However, none of these definitions in these resources adequately represents the concept of collaboration as it exists or should exist in the provision of health and illness care. On the basis of a review of the literature and our experience, this definition of collaboration as a dynamic, interpersonal process was developed for the first edition of this text (Hanson & Spross, 1996): “Collaboration is a dynamic, interpersonal process in which two or more individuals make a commitment to each other to interact authentically and constructively to solve problems and to learn from each other to accomplish identified goals, purposes, or outcomes. The individuals recognize and articulate the shared values that make this commitment possible.” (Hanson & Spross, 1996, p. 232). Characterizing collaboration as an interaction is intended to convey the communicative and behavioral aspects of this competency. Our definition implies partnership, shared values, commitment, and goals and yet allows for differences in opinions and approaches. It also acknowledges that collaboration requires individuals to interact holistically (strengths, weaknesses, emotions) and authentically, to share power, and to remain open to the possibilities for personal and professional transformation that exist within a collaborative relationship. Including the notions of shared values and commitment makes it clear that collaboration is a process that evolves over time. Collaboration engages the head, the heart, and the will (Senge, Scharmer, Jaworski, & Flowers, 2004). These three “thresholds” are the essence of collaboration and are consistent with our definition. The clinician who is caring for a patient seeks advice regarding a patient’s concern but retains primary responsibility for care delivery (see Chapter 9). Two or more clinicians provide care and each professional retains accountability and responsibility for defined aspects of care. This process usually arises from consultation in which a problem requires management that is outside the scope of practice of the referring clinician (see Chapters 9 and 17). Providers must be explicit with each other about their responsibilities. Comanagement may also be a process used by interdisciplinary teams, such as palliative care. Collaboration with patients, families, and colleagues in the delivery of direct care is the primary domain in which collaboration is practiced. For example, in forming partnerships with patients (see Chapter 7), APNs aim to understand how the patient wants to work with the APN and other providers. APNs collaborate with patients and families when they set and revise goals and determine barriers to adherence; these activities are aimed at uncovering a common purpose, a hallmark of collaboration. APNs also collaborate with individual clinicians. For example, the diabetes clinical nurse specialist (CNS) may collaborate with the cardiac CNS and a staff nurse to determine who will carry out which aspects of patient education for a patient. The collaborative process may include determining the order and timing of content to be taught. In this case, the APN is also executing the direct care (interacting with the patient to assess learning needs) and coaching (coaching patients in lifestyle changes) competencies. Another common domain in which APNs implement collaboration is in their work with clinical teams and on departmental and institutional committees. These groups may be comprised of individuals from one or more disciplines. A key function of the collaborative competency is the facilitation of teamwork to ensure the delivery of effective, safe, high-quality care leading to positive outcomes. The literature and our experience suggest that APNs play key roles in facilitating and leading interdisciplinary teams. As APNs become more experienced, their skill in facilitating collaboration in groups grows. Thus, APNs often lead interdisciplinary performance improvement teams, an activity that requires integration of the collaboration and leadership competencies (see Chapter 11). In this domain, the focus of collaboration extends beyond the delivery of care to individuals and groups. The organizational and policy forces shaping advanced practice nursing and clinical care require that even novice APNs attend to collaboration in this area. Initiatives aimed at clarifying credentialing requirements, making it easier to practice across state lines, and improving reimbursement for APNs require APNs to use their status as clinicians, citizens, and members of professional organizations to collaborate with organizational leaders and policymakers. See national APN websites and that of the Nursing Alliance for Quality Care (www.gwumc.edu/healthsci/departments/nursing/naqc). Global or international collaboration is becoming an essential collaborative domain within the APN collaboration competency (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2006; Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2011; National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties [NONPF], 2011). See Chapter 6. Friedman (2005) has argued that global communication and collaboration will be the keys to successful living, working, and economic success over the next century, and we believe that this is true for health care. There is evidence that globalization is already affecting practice; the APN covering the emergency room at night may be communicating with a radiologist in Australia about a diagnostic image that was sent electronically to be interpreted in real time. In addition, APNs’ experiences with volunteerism in other countries (e.g., Doctors without Borders, mission trips to Haiti and Africa) are shaping APN goals and opportunities. Nursing leaders across the globe are meeting to further nursing’s contributions to education and practice (see www.icn.ch). The terms multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary and, most currently, interprofessional collaboration are often used interchangeably. There are subtle but important differences among these terms; the prefix actually indicates the level and depth of interactions to which the term refers. The differences were best expressed in work by Alberto and Hearth (2009), D’Amour, Ferrada-Videla, Rodriguez, et al. (2005), and Garland, McConigel, Frank, et al. (1989). A key difference among the terms is reflected in the philosophy of team interaction. In a multidisciplinary team, the philosophy of team interaction is a simple recognition of the importance of the contributions of other disciplines. In an interdisciplinary team, members willingly share responsibility for providing care or services to patients. In a transdisciplinary team, members are committed to teaching each other, learning from each other, and working across boundaries to plan and provide integrated services to clients (Garland et al., 1989). Interprofessional collaboration takes these types of collaboration a bit further to eliminate traditional prescribed boundaries through negotiation and interaction (Alberto & Hearth, 2009; Bainbridge, Nasmith, Orchard, et al., 2010; Interprofessional Education Collaborative [IPEC], 2011). Interprofessional collaboration has been described as the “interactions of two or more disciplines involving professionals who work together with intention, mutual respect and commitment for the sake of a more adequate response to a human problem.” (Harbaugh, 1994, p. 20). More recently, Petri (2010) has suggested that it is an interpersonal process characterized by health care professionals with shared objectives, decision making responsibility, and power working together to solve patient care problems. IPEC (2011; Schmitt, 2011), a partnership made up of the AACN, American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine, American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, American Dental Education Association, Association of American Medical Colleges, and Association of Schools of Public Health furthers this definition with their goal to prepare all health professions students to work together deliberatively to build a safer and better patient- and community-centered health care system in the United States. To this end, IPEC has developed core domains and competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice based on four domains, described in Box 12-1. Each IPEC domain has several behaviors that further define the competency (IPEC, 2011). The move to reintroduce team approaches to care is evident across the spectrum of health care today (Clausen, Strohschein, Farems, et al., 2012; HHS, 2011; IOM, 2011; Young, Siegel, McCormick, et al., 2011). APNs should aspire and help teams achieve interprofessional collaboration. Interprofessional and transdisciplinary work foster the development of new understanding and new fields of inquiry in clinical care. We propose that this level of interaction leads to new insights in the interpretation of assessments and creative and effective clinical problem solving, leading to successful outcomes. There is a heightened urgency to ensure that collaboration occurs. The need for collaboration among health care professionals is not a new concept, but has been a serious concern over many years (Bainbridge et al., 2010; Dumez, 2011; Petri, 2010; World Health Organization, 1978). Efforts to transform the health care system to improve reliability of care, safety, quality, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness will fail if clinicians, teams, and administrators do not undertake the important collaborative work necessary to effect this transformation. Several phenomena have coalesced to bring the struggles to attain interprofessional collaboration to a critical point. The IOM report on quality and safety in the late 1990s (IOM, 2001), identified shortages, especially in primary care, and the need for team approaches through community-based care, ACOs (accountable care organizations), and nurse-managed clinics proposed in the PPACA. In addition, the latest IOM report (2011), The Future of Nursing, has urged teamwork among health care providers. These have all led to a resurgence of the need to foster interpersonal and interprofessional competency for all health care providers. The pressing need for collaboration among health care professionals led to the development of specific interprofessional competencies in 2011 (Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative [CIHC], 2010; HHS, 2011; IPEC, 2011). A paradox of the contemporary health care system is that there are incentives and disincentives for members of different disciplines, work groups, and organizations to collaborate. Incentives and disincentives may be equally powerful, so that motivation to collaborate can be diminished or eliminated by a compelling counterforce (Fig. 12-1; Young et al., 2012). An understanding of this paradox can help APNs and their colleagues approach opportunities for collaboration strategically and build and sustain clinical environments that support collaboration. Numerous clinical initiatives aimed at improving quality and safety, the need to eliminate health care disparities, and an increasing proportion of nonphysician health care professionals underscore that interprofessional collaboration at the educational, clinical, and institutional levels is essential in the current health care marketplace (American College of Graduate Medical Education, 2002; Cronenwett & Dzay, 2010; Disch, 2002; IOM, 2011; Schmitt, 2011; Pohl, Hanson, Newland, et al., 2010; Lindeke, 2005). The ability to collaborate is essential if future APNs are to implement interdisciplinary practice models and analyze complex health problems in an interactive environment (AACN, 2006; Cronenwett & Dzay, 2010; IOM, 2011; Pohl et al., 2010). The definitions of collaboration and interprofessional collaboration proposed in this chapter invite exploration of the characteristics that make up a successful collaborative relationship. Personal- and setting-specific attributes are pivotal to successful professional collaborations. Some characteristics of collaboration have long been recognized and promulgated, but too often clinicians and organizations have resisted adopting the philosophy, commitment, and behaviors necessary to develop collaborative practices. Steele’s analysis (1986) of collaboration among NPs and physicians has revealed several characteristics—mutual trust and respect, an understanding and acceptance of each other’s disciplines, positive self-image, equivalent professional maturity arising from education and experience, recognition that the partners are not substitutes for each other, and a willingness to negotiate. In their program of research, Baggs and Schmitt (1988, 1997), noted the following characteristics of collaboration between registered nurses and physicians: assertiveness, shared decision making, communication, planning together, and coordination. Petri (2010) and Hughes and Mackenzie (1990) have outlined four characteristics of NP-physician collaboration: collegiality, communication, goal sharing, and task interdependence. Spross (1989) has described three essential elements of collaboration: a common purpose, diverse and complementary professional knowledge and skills, and effective communication processes. Although this is not an exhaustive summary of the literature on collaboration, it is clear that certain core elements characterize collaboration; these are listed in Box 12-2. The domains and competencies described by IPEC and the CIHC further explicate the attributes and competencies of interprofessional collaboration. The discussion of characteristics of collaboration that follows elaborates on each of these elements. However, the reader will notice their overlapping and interlinked nature because many are mutually dependent on others for full collaboration to be realized. Collaboration requires clinical competence, common purpose, and effective interpersonal and communication skills (or a willingness to learn them). Trust, mutual respect, and valuing each other’s knowledge and skills are equally important but develop fully only over time. For these characteristics to develop, prospective partners must approach encounters with a willingness to trust, commitment to respect each other, and assumption that the other’s knowledge and skills are valuable. In one sense, these characteristics are therefore prerequisites; however, they are fully realized only after many constructive and productive interactions. Finally, a sense of humor among team members serves many functions in helping team members stay committed to each other’s collaborative practice (Balzer, 1993; Hanson, 1993). Clinical competence is perhaps the most important characteristic underlying a successful collaborative experience among clinicians; without it, the trust and desire needed to work together are not possible. Trust and respect are built on the assurance that each member is able to carry out his or her role, function in a competent manner, and be accountable for his or her practice. Clinical competence is a critical element of collaboration and has been validated in research (Bosque, 2011; Hanson, Hodnicki, & Boyle, 1994; Prescott & Bowen, 1985), yet stereotyped views of nursing and medical practice may interfere with collaborative efforts. Physicians are sometimes perceived as all-knowing and as having ultimate responsibility for patient care, whereas nurses may be viewed as nonintellectual, second-best substitutes for excellent health care (Fagin, 1992; Sands, Stafford, & McClelland, 1990) who have little authority or responsibility for patient care outcomes (Larson, 1999). The status of advanced practice nursing is still such that nurses must prove their competence to the profession and to society (Fagin, 1992; Hanson, Hodnicki, & Boyle, 1994; Prescott & Bowen, 1985; Safriet, 2002, 2010). When collaborating clinicians can rely on each other to be clinically competent, mutual trust and respect develop. Partners recognize that leadership is problem-based, not team- or role-based, and are open to sharing power. Instead of one person always being the team leader, leadership can shift among partners in a departure from the traditional captain of the team approach. Thus, the person with the most expertise, interest, or talent can respond to the particular demands of the situation or problem. The recent ACO and Medical Home concepts (American Academy of Family Physicians [AAFP], American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association, 2007; HHS, 2011) are excellent examples of how this approach could work (see Chapter 22). The trust and respect among collaborators is such that they can count on satisfactory resolution of the problem, even when they know as individuals that they might have approached the issue differently. This openness to shared leadership and alternative solutions allows partners to learn from each other. For example, APNs usually have expertise in educating patients about their illnesses and lifestyle choices, and physicians are often expert diagnosticians. Therefore, collaboration offers APNs and physicians opportunities to model their varied assessment and intervention strategies, which fosters mutual learning and appreciation for the contributions of each to the care of patients and families. Being accountable for practice enhances collaboration. APNs who share in planning, decision making, problem solving, goal setting, and assuming responsibility are modeling full partnership on caregiving teams (Baggs & Schmitt, 1988; Clausen, Strohschein, Farems, et al., 2012; IPEC, 2011). The notion that a common purpose must be the basis for collaboration has been well supported in the literature (Alberto & Herth, 2009; Murray-Davis, Marshall, Gordon, et al., 2011; Nolan, Resar, Haraden, et al., 2004; Petri, 2010; Spross, 1989). Even if partners have not discussed the purposes and goals of their interactions, the organizations in which they work usually have an explicit mission and goals. Goals can be the starting point for identifying the purposes of clinical collaboration. Common purposes may range from ensuring that an underserved patient gains access to preventive services, such as mammography, to a more ambitious quality improvement agenda to improve the management of heart failure patients across settings. One of the paradoxes of collaboration is that the partners are autonomous (self-governing, accountable) but interdependent, reflecting a reciprocal reliance on each other for support in carrying out their responsibilities. Recognizing their interdependence, team members can combine their individual perceptions and skills to synthesize care plans that are more complex and comprehensive than what they could have created working alone. Like other characteristics, the common purpose that initially brought partners together may change over time. The situation that brought two clinicians together may become secondary to the deep personal commitment to work together in ways that improve patient care and are interpersonally and professionally satisfying. In addition to a common purpose, partners who are guided by a shared vision of the possibilities inherent in collaboration, believe in the value of collaboration, and committed to achieving the relationship’s potential (Lindeke, 2005; Young et al., 2012) will be most able to move toward transdisciplinary and interprofessional collaboration. Developing a shared vision does not negate the differences among partners’ ideas, opinions, and actions. On the contrary, it permits—and may even value—such differences. In light of corporate, governmental, and research scandals, the concept of transparency of communication and behavior has emerged in health care today. The IOM’s Crossing the Quality Chasm lists transparency as one of the rules for the twenty-first century health care system (IOM, 2001). The term transparency can be defined as the honest and open sharing of information and ideas. It includes open communication among parties, keeping everyone in the loop. It also means that one does not dissemble or pretend that everything is fine when it is not. Transparent communications are closely linked to accountability; transparency engenders trust and thus is an underlying requisite for collaboration. After clinical competence, interpersonal competence and effective communication may be the most important characteristics needed for APNs to establish collaborative relationships. A lack of knowledge about another’s discipline is thought to be a barrier to developing effective teamwork (Dumez, 2011; Gilbert, Camp, Cole, et al., 2000). Partners must recognize and value the overlapping and diverse skills and knowledge that each discipline brings to the team (CIHC, 2010; IPEC, 2011; Spross, 1989) so that mutual trust and respect can develop and deepen over time. Partners observe that patients benefit from their combined talents and efforts. They come to depend on each other to use good clinical judgment and to take appropriate actions. Initially, collaborators have limited knowledge of each other as individuals and as professionals; collaboration is a “conscious, learned behavior” that improves as team members learn to value and respect one another’s practice and expertise (IPEC, 2011; Moeller, Vezeau, & Carr, 2007). The first step is to recognize these differing contributions. Medicine and nursing, although overlapping disciplines, are culturally distinct and have diverse goals for patient care. In many cases, they complement each other in their quest to restore patients to health. These complementarities also extend to other disciplines. Collaboration is built on the respect and valuing of the contributions of each profession to the common goal of optimal health care delivery. A final important aspect of the collaborative process is humor. Humor in which the intent is positive and nonthreatening is a creative way to set the stage for effective communication and problem solving among members of different disciplines (Balzer, 1993; Hanson, 1993). In collaborative practice, humor serves to decrease defensiveness, invite openness, relieve tension, and deflect anger. It helps individuals keep perspective and acknowledge the lack of perfection, and it sets the tone for trust and acceptance among colleagues so that difficult situations can be reframed (Balzer, 1993). Ciesielka, Conway, Penrose, & Risco (2005) suggested that humor is essential to successful collaboration because it is a bridge to different backgrounds. The use of humor helps defuse the need for persons to argue their own point of view and allows them to refocus on how they can work together to meet common goals (Hill & Hewlett, 2002). Graduate students can be encouraged to observe how humor is used by preceptors and colleagues and identify those uses that seem effective for improving communication and defusing conflict situations. Although this list of characteristics of effective collaboration may seem daunting to the novice, a consistent commitment to and practice of collaboration can develop this competency over time in an APN’s practice. Exemplar 12-1 showcases the elements of collaboration in an individual APN’s practice. APNs and their professional colleagues need to recognize that an important component of clinical practice is investing the time and energy to build these relationships. The high levels of interchange of ideas and expertise that become possible when all of these characteristics come together is one of the great satisfactions of collaborative practice. Experience and evidence suggest that collaboration works, but effective collaboration eludes many clinicians. Why? Some authors link barriers to the history of the health care professions, traditional gender roles, disciplinary heritage, ineffective communication, and hierarchical relationships (Christman, 1998; Larson, 1999; Reuben, Levy-Storms, Yee, et al., 2004; Rosenstein & O’Daniel, 2005; Zwarenstein & Reeves, 2002). Over the years, there have been many reports of successful collaborative relationships involving APNs (Brooten, Youngblut, Blais, et al., 2005; Cowan, Shapiro, Hays, et al., 2006; Lindeke, 2005; Naylor, Brooten, Campbell, et al., 2004.). The importance of collaboration in various aspects of advanced practice nursing continues to be recognized (Bosque, 2011; Ingersoll, McIntosh, & Williams, 2000; Kleinpell, Faut-Callahan, Lauer, et al., 2002; Sheer, 2007; Young, et al., 2011). Although few studies of collaboration have measured patient outcomes systematically (Litaker, Mion, Planavsky, et al., 2003; McCaffrey, Hayes, Stuart et al., 2010; Wooton, Lee, Jared, et al., 2011; see Chapter 24), patient and provider benefits have been documented. Patients are sensitive to the relationships among caregivers and are quick to pick up on the lack of respect or trust among their providers. Some research has suggested that collaborative relationships among interdisciplinary health care providers can ameliorate some of these negative effects (Remonder, Koch, Link, et al., 2010; Weinstein, McCormack, Brown, et al., 1998). Successful collaborative practices are those in which patients easily move back and forth between providers as their care and situations dictate. Collaboration requires an ability to transform competitive situations into opportunities for working together that are mutually beneficial, and in which all parties can imagine the possibility of creating a win-win situation. Studies of the impact of APNs on disease management and care transition interventions indicate that there are positive outcomes for patients. Collaboration is implied based on the fact that the APNs in these studies typically communicated with other providers, but collaboration is rarely identified or measured (these studies are discussed in Chapter 24). Table 12-1 illustrates the types of patient and provider benefits that have been ascribed to clinical collaboration. Collaboration competencies have been in place for APNs for several years (AACN, 2006; NONPF 2011). New competencies required by the American College of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) for participants in medical residency programs include behaviors related to interdisciplinary teamwork, group problem solving, and communication across settings. These collaborative expectations were adopted in 2002 by the ACGME. Adapted from Sullivan, T.J. (1998). Collaboration: A health care imperative (pp. 26–27). New York: McGraw-Hill Health Professionals Division.

Collaboration

Definition of Collaboration

Collaboration: What It Is Not

Consultation.

Comanagement.

Domains of Collaboration in Advanced Practice Nursing

Collaboration with Individuals

Collaboration with Teams and Groups

Collaboration in the Organizational and Policy Arenas

Collaboration in Global Arenas

Types of Collaboration

Interprofessional Collaboration

Characteristics of Effective Collaboration

Clinical Competence and Accountability

Common Purpose

Interpersonal Competence and Effective Communication

Recognizing and Valuing Diverse, Complementary Culture, Knowledge, and Skills

Humor

Impact of Collaboration on Patients and Clinicians

![]() TABLE 12-1

TABLE 12-1

Collaboration

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access