Code Sets

Marion Gentul

Chapter Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the student should be able to:

1. Describe the general purpose of coded data in relation to its various uses.

2. Name the transaction code sets required under HIPAA.

3. Describe the format of ICD-10-CM.

4. Describe the format of ICD-10-PCS.

5. Describe different coding and classification systems and their uses.

Vocabulary

American Medical Association (AMA)

American Psychiatric Association (APA)

case mix

classification

Cooperating Parties

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT)

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)

electronic data interchange (EDI)

Federal Register

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS)

HIPAA Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting

ICD-10-CM

ICD-10-PCS

ICD-9-CM

ICD-O

Interactive Map-Assisted Generation of ICD-10-CM Codes (I-MAGIC) algorithm

International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation (IHTSDO)

multi-axial

National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)

National Drug Codes (NDC)

National Library of Medicine (NLM)

nomenclature

SNOMED-CT

standards for code sets

Standards of Ethical Coding

transaction code sets

World Health Organization (WHO)

Coding

Coding is discussed in Chapter 5 as an element of postdischarge processing. This chapter focuses on several of the most commonly used coding systems and on how and when codes are used for health care reimbursement.

Although the coding function is most often associated with payment and reimbursement, coded data are used for other, equally important purposes. For example, coding professionals are key players in ensuring providers’ compliance with official coding guidelines and government regulations. The statistical data collected from complete and accurate coding are necessary to provide a facility or health care provider with the following:

• Resource utilization information: volume and disease data

• Databases for maintaining indices and registries: lists of diagnosis, procedure, and physician data (see Chapter 10)

• Physician practice profiling information: physician volume data

• Research and clinical trials

• Evaluation of the safety and quality of care

• Quality and outcomes measurements

• Prevention of health care fraud and abuse

• Other administrative initiatives and activities, such as audits and productivity analysis

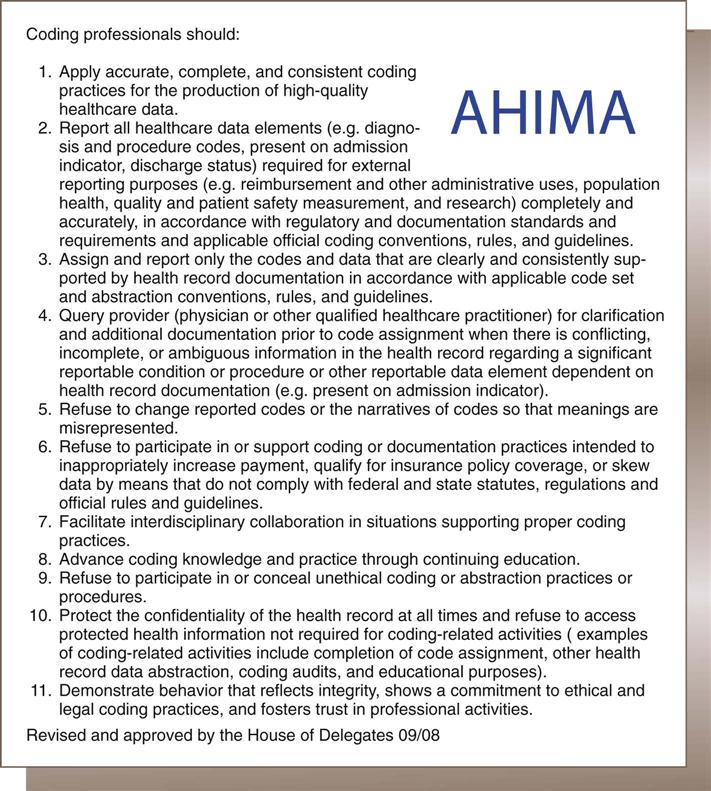

On the patient level, the codes assigned to diagnoses and procedures for an individual patient’s encounter or hospital stay may follow that patient throughout the health care delivery system and have an impact on future treatments and insurability. In the quest for fast billing turnaround time and payment, it is sometimes easy to forget that the patient record is a highly personal document, one that often describes a person’s last days, and therefore must be treated respectfully with regard to the coded data assigned. The American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA) has issued “Standards of Ethical Coding,” guidelines that all coders, regardless of setting, should be aware of and follow (Figure 6-1).

Coding is essentially the translation of documented descriptions of diagnoses (e.g., diseases, injuries, circumstances, and reasons for encounters) into a numerical or alphanumerical code. Thus the diagnosis hypertension is translated to the code I10. The same can be said of translating documented descriptions of procedures, services, or treatments. Coding standardizes the communication of clinical data between users and facilitates electronic transmission of clinical data.

Of interest to coders today are the standards for code sets under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, which names standards for exchanging information through the use of codes. Under HIPAA, transaction code sets are sets of codes used to communicate the diagnosis and procedure codes, data elements, and medical concepts used in electronic health care transactions transferred through an electronic data interchange (EDI). The code sets used in the EDI were mandatory for use in reporting and reimbursement using electronic transaction format version 5010, effective January 1, 2012. The electronic version of a Uniform Bill (UB-04), for example, is the 837I, which is sent in 5010 format. Transaction code sets prior to October 1, 2014, are as follows:

• National Drug Codes (NDCs), used for defining drugs by name, manufacturer, and dosage

• Current Dental Terminology (CDT), for dental terms

Effective October 1, 2014, ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS replace ICD-9-CM Volumes I, II and III.

Coded data are also retained in electronic format within a facility, such as a hospital, or for a provider, such as a physician office. This coded data can also be shared within a network. Imagine attempting to share information about hundreds or thousands of patients without translating the written descriptions of diagnoses and procedures into codes, and one begins to appreciate the complexity of coded data and the importance of those who perform the coding function.

Many coding systems are in use today throughout the United States and the world. The United Kingdom, for example, uses the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys (OPCS-4) Classification of Interventions and Procedures, a coding system comparable to the ICD-10; Canada developed an adaptation to the ICD-10, ICD-10-CA. The word international can be found in the titles of many of these different coding systems. For example, the International Medical Terminology, for the reporting of regulatory activities, was developed under the auspices of the International Conference on Harmonization of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) (National Center for Biomedical Ontology, 2012). Some systems are sponsored and maintained by governmental agencies and others by various medical or health associations in the United States and internationally. In the United States, the coding system used depends on the applicable HIPAA transaction code set used in the provider setting. For example, inpatient hospital-based coders use transaction code sets ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS effective October 1, 2014.

This chapter focuses on HIPAA transaction code sets, including ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS, and HCPCS/CPT-4. Other important coding systems, including SNOMED-CT, are also discussed.

Nomenclature and Classification

There are two basic types of coding systems: nomenclature and classification. A nomenclature is a system of naming things. Scientific and technical professions typically have their own nomenclatures. A number of different nomenclatures are used in medicine. A common nomenclature is found in the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT). Nomenclatures facilitate communication because the users have available the specific definition of the codes. For example, HCPCS code G0010 represents the administration of Hepatitis B vaccine, and HCPCS code G0027 (the next G code) represents semen analysis; presence and/or motility of sperm excluding Huhner. Although many HCPCS codes are related to the next sequential code, there is no global relationship from one code to the next, and the purpose of the assignment of codes is primarily to enable users to communicate efficiently and effectively via computer data entry.

In addition to nomenclatures, classification systems are very important in health care. The primary disease classification system used in health care delivery systems is the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). ICD is used worldwide and is in its tenth revision (ICD-10). In the United States, it has been modified to increase its level of detail and to add procedural coding. Classification systems group codes so that coding sequences have logical relationships. For example, ICD-10 groups diagnoses by body system and sequences related conditions together. I21 is the ICD-10 category for acute myocardial infarctions, and I25 is the category for coronary artery disease. Subcategories describe the location, episode, or extent of the condition.

Health information management (HIM) professionals must be knowledgeable about the coding systems used in the setting in which they are employed. Many HIM professionals are coders; however, a great deal of data analysis and reporting also occurs in health care, much of it in coded format. Therefore students of HIM should pay particular attention to developing sufficient coding skills to enhance their career opportunities.

General Purpose Code Sets

ICD-9-CM

Coding for disease nomenclature purposes began in the 18th century with the attempt to name diseases. The first classification system, the Bertillon Classification of Causes of Death, was adopted by the International Statistics Institute (ISI) in 1893. Named after Jacques Bertillon, the chair of the ISI committee that developed the system, the Bertillon Classification of Causes of Death was adopted in the United States in 1899. Although some morbidity classifications were being developed at this time as well, it was not until 1948 that the adoption of classifications for disease took root and the sixth revision of the Bertillon Classification was incorporated into the Manual of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Injuries, and Causes of Death under the auspices of the World Health Congress. This also marked the beginning of the formal international effort to coordinate mortality reporting from national committees of vital and health statistics to the World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO continued to revise the morbidity and mortality classification system, currently called the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) (World Health Organization, 2011).

The United States lags behind the rest of the world in adopting ICD-10 for general use. WHO member nations began implementation of ICD-10 in 1994; however, the United States used it only for mortality reporting. The United States has continued to use ICD-9 as the basis for its clinical modification of the ICD-9 code set (ICD-9-CM) while it evaluated and eventually developed ICD-10-CM.

When ICD-9-CM was mandated for use in 1979, it really had no special purpose other than to ensure an updated and unified coding system in the United States. Coding became directly linked to reimbursement in 1983 with the implementation of the diagnosis-related group (DRG)–based hospital prospective payment system (PPS).

Although ICD-9-CM is scheduled to be replaced by ICD-10-CM/PCS, it is still important for HIM professionals to have at least a basic understanding of it. It is unlikely that organizations will convert their databases to ICD-10-CM/PCS, so historical data will continue to be displayed and used in ICD-9-CM format. Further, historical data will be subject to audits and used for research purposes and for longitudinal studies of coded data.

ICD-10-CM

ICD-10-CM is published by the United States Government. The foundation of ICD-10-CM is the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, or ICD-10, published by the World Health Organization. With some variations, ICD-10 is also used in approximately 100 countries. ICD-10-CM is scheduled to replace ICD-9-CM Volumes I and II effective October 1, 2014.

ICD-10-CM contains characteristics that were not available in previous versions of the clinical modification of ICD. ICD-10-CM’s structure is such that considerable expansion is possible, enabling the addition of new, specific codes as needed without compromising the general code structure.

ICD-10-CM consists of two main parts, the Index to Diseases and Injuries (the main index), and the Tabular List of Diseases and Injuries (the main tabular list). The Index consists of an alphabetical listing of terms followed by their corresponding complete or partial (incomplete) codes. The incomplete codes found in the Index must be completed, on the basis of additional information and instruction in the Tabular, to become valid codes. The Tabular is the complete list of codes, in numerical order. It is essential to use both the Index and Tabular for code assignment, because instruction notes and other elements such as punctuation in both the Index and Tabular must be followed. These instruction notes, called conventions and guidelines, are found in the HIPAA Official Guidelines for Coding and Reporting. The Official Guidelines are updated each October. They can be located in the CDC Web site; for example, the link to the 2011 Official Guidelines is http:// www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/icd9/10cmguidelines2011_FINAL.pdf.

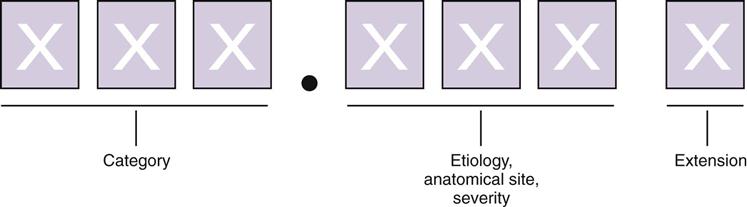

ICD-10-CM codes are alphanumerical; a letter is always the first character in each code. The first three characters represent the code category. Characters four, five, and six represent etiology, anatomical site, and severity, respectively. Valid codes range from three to six characters in length. Certain code categories have applicable seventh characters, or code extensions, the meaning of which depends on the code and chapter where it is required. In the event that a code requiring a seventh character extension is less than six characters in length, a placeholder character, “x,” is used to ensure that the seventh character extension is in the seventh character data field. See Figure 6-2 for an illustration.

Other unique features of ICD-10-CM include expanded injury codes, more codes relevant to ambulatory and outpatient encounters, combination codes, and classifications specific to laterality.

The main index also contains the Index to External Causes of Injury, the Neoplasm Table, and the Table of Drugs and Chemicals, all with corresponding codes in the main tabular.

ICD-10-CM can be downloaded in either PDF (printer-downloadable format) or XML (Extensible Markup Language) format from the CDC’s Web site; the draft of the 2013 ICD-10-CM can be found here: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm#10update.

In the United States, the Cooperating Parties are responsible for ICD-10-CM. The Cooperating Parties consist of representatives of the American Hospital Association (AHA), AHIMA, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and NCHS. The Cooperating Parties meet twice yearly, usually in April and October, to hear and discuss proposed code changes or revisions. Anyone can attend these meetings. Notices and agendas can be found on the CMS Web site in the Federal Register section at http://www.gpoaccess.gov/fr. If and when a proposed code change meets final approval, it can be accessed in the Federal Register section as a Final Rule. Coding changes may be approved and issued for use twice yearly, in April and October, although most major changes are effective in October.