Chapter 20. CNS 3. Antipsychotics, anxiolytics and hypnotics

Introduction264

Types of mental illness264

Brain neurotransmitters and psychiatric disorders264

Antipsychotic drugs264

Administration of drugs to psychiatric patients – general points 264

Classification of antipsychotic drugs 265

Mechanism of action of antipsychotic drugs 265

Therapeutic use of typical antipsychotic drugs 265

Therapeutic use of atypical antipsychotic drugs 268

Depot injections 268

The treatment of schizophrenia 268

Management of acute confusional states 269

Summary277

At the end of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• identify some brain neurotransmitter receptors known to be important targets for drug action in psychiatry

• discuss the special implications of administering drugs to patients with mental health problems

• give an account of the broad classification of antipsychotic drugs into typical and atypical, with examples

• provide examples of the phenothiazines and the other classes of antipsychotic drugs, their use and adverse effects

• give an account of the nature and treatment of schizophrenia, and the management of the schizoid patient

• discuss what is meant by the acute confusional state and its dangers for elderly patients and its treatment and patient care

• give an account of the different classifications of anxiety and know the different classifications of anxiolytic drugs

• give the names of specific benzodiazepines, their therapeutic use and adverse effects, and know what is meant by ADHD

Introduction

Mental illness is one of the major causes of ill health. Many drugs have been produced in the hope that they would have some therapeutic effect. Certain mental illnesses, particularly depression and schizophrenia, are linked with chemical abnormalities in the brain. The nature of some of these abnormalities is known, but there are considerable gaps in our knowledge. Nevertheless, the knowledge gleaned so far from medical research has resulted in the introduction of drugs that are designed to target brain mechanisms that may mediate mental illnesses.

Types of mental illness

The treatment of psychiatric disorders can be considered in terms of three main types of disorder: psychosis, anxiety and depression.

Psychosis is a term used to describe disorders when the patient loses contact with reality. Features of psychosis include paranoia, schizophrenia, manic behaviour, toxic delirium (delirium caused by the action of a poison), severe thought disturbance or poverty of thought. Terms such as ‘delusions’ and ‘hallucinations’ are sometimes used to describe the symptoms of psychosis.

Anxiety is a term used to describe a condition of generalized, all-pervasive fear. It is featured by an emotionally inappropriate response to the patient’s environment and to circumstances. Traditionally, patients were termed ‘neurotic’ but this term is no longer favoured in some clinical circles. Commonly used lay and professional terms to describe the symptoms of anxiety include ‘panic attacks’, generalized panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. This list keeps growing due to the practice of labelling the circumstances that generate anxiety.

Depression is a blanket term for several disorders that are characterized by changes in mood rather than in thought or emotional response. Professionals describe depression as an affective disorder. Symptoms can range from extreme sadness to suicidal intent. Depression is dealt with in Chapter 21.

Brain neurotransmitters and psychiatric disorders

Many of the drugs that have been introduced for the treatment of psychotic disorders are known to interfere with the normal action of several of the brain neurotransmitters and their receptors. The major brain neurotransmitters that have been implicated in psychiatric disorders are:

• acetylcholine (ACh)

• adrenaline

• noradrenaline

• dopamine

• 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT; serotonin)

• GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid)

• neuropeptides.

The amounts of adrenaline and noradrenaline are increased in the brain by giving drugs such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), which are drugs that retard their breakdown. Tricyclic antidepressants inhibit the reuptake of catecholamines into the nerve terminals. Thus, an awakening and stimulating effect is produced, and these drugs are used as antidepressants (see Chapter 21). If the amounts of catecholamines in the brain are reduced, a tranquillizing or depressing effect is produced; 5-HT also seems to be concerned with mood, whereas GABA exerts a sedating inhibiting effect. Dopamine stimulates more than one class of receptor: it causes nausea and vomiting but also appears to be concerned with the schizoid state. In fact, the evidence suggests that the efficacy of many antipsychotic drugs can be correlated, approximately, with their ability to block dopamine D 2 receptors (see more below).

Antipsychotic drugs

Administration of drugs to psychiatric patients – general points

• In hospital, many people with mental health problems are not confined to bed and drugs may be administered at a central point rather than having a ‘drug round’.

• Two nurses should always be concerned with drug administration.

• In psychiatric units, patient compliance may be a problem and it is necessary to ensure that medication is actually taken. For example, patients may put the tablets in their mouths, but spit them out when no longer observed by the nurse.

• Occasionally, a patient’s paranoia may extend to drugs they are given. They may think the staff are trying to poison them.

• Drug education for when the patient returns home is very important and relatives may have to be involved. Non-compliance is an important hazard as the patient’s illness may relapse if treatment is stopped. It should also be possible for patients or relatives to have contact numbers to call for information if problems arise.

• The nurse should observe the effects of drug treatment.

• On discharge, care should be taken not to prescribe excessive quantities of drugs, particularly if there is a suicide risk.

Classification of antipsychotic drugs

Traditionally, antipsychotic drugs such as chlorpromazine (see below) have been referred to as major tranquillizers, while anxiety-suppressing drugs such as the benzodiazepines (see Chapter 21) have been called minor tranquillizers. This terminology is generally no longer in favour and will not be used here. Antipsychotic drugs are also called neuroleptics, and this term is still widely used. Antipsychotic drugs, because of their diverse chemical nature and wide range of pharmacological actions, are notoriously difficult to classify, but the currently favoured broad classification is into two main types:

• classical or typical antipsychotic drugs, which are generally those that have been in use for many years

• atypical antipsychotic drugs, which are more recent additions to the repertoire of drugs available.

This distinction is based partly on the fact that some of the newer (atypical) drugs produce fewer adverse effects on the motor system, such as tremor, and that the atypical drugs may help patients who do not respond to the older, typical drugs.

Examples of typical antipsychotic drugs:

• benperidol

• chlorpromazine

• flupentixol

• fluphenazine

• haloperidol

• levomepromazine

• pericyazine

• perphenazine

• pimozide

• prochlorperazine

• promazine hydrochloride

• sulpiride

• trfluoperazine

• zuclopenthixol acetate

• zuclopenthixol dihydrochloride.

Examples of atypical antipsychotic drugs:

• amisulpride

• aripiprazole

• clozapine

• olanzapine

• quietiapine

• risperidone

• sertindole

• zotepine.

Mechanism of action of antipsychotic drugs

Virtually all antipsychotic (neuroleptic) drugs have so many different pharmacological actions that it is very difficult to relate any one action to a therapeutic effect. The only statement that can be made with reasonable confidence is that most, if not all, effective antipsychotic drugs share the ability to block dopamine D 2 receptors in the brain.

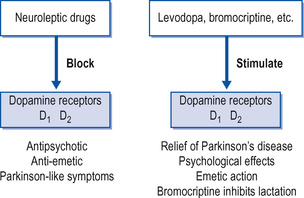

These drugs are particularly useful in controlling the states of agitation found in acute schizophrenia, mania and some other forms of delirium and in paranoia. Their exact mode of action in these conditions is not known but most of them block the action of dopamine on D 2 receptors in the mesolimbic system of the brain and this seems important in their sedative and antipsychotic action (Fig. 20.1). They also block the action of dopamine on the brain CTZ (chemoreceptor trigger zone) and are thus antiemetic. Some, such as haloperidol (see below), block the action of the dopaminergic nerves that run from the substantia nigra to the corpus striatum. Interruption of this system causes parkinsonism (see p. 257) and so these drugs may cause various disorders of movement and posture (see later).

|

| Figure 20.1 Effect of drugs on dopamine receptors in the brain. The exact part played by D 1 and D 2 receptors and other subgroups is not known. |

Therapeutic use of typical antipsychotic drugs

The typical antipsychotic (neuroleptic) drugs are:

The phenothiazines

Therapeutic uses and effects

Phenothiazines have an antipsychotic effect. Restlessness, agitation and hallucinations are reduced and this has made them especially useful for treating schizophrenia. They produce some sedation with a feeling of detachment from external worries. Many of them have some antiemetic action. Chlorpromazine is sometimes used to control persistent hiccup. Most of the phenothiazines are well absorbed after oral dosage. They are largely metabolized in the liver to numerous breakdown substances.

The phenothiazines are used in psychiatry to reduce restlessness, anxiety and agitation in psychotic patients and to reduce the severity of hallucinations. They are thus useful for controlling schizophrenics who show these symptoms. They are sometimes used in low doses in psychoneurosis with anxiety. They are, in addition, used as antiemetics, in severe pruritus and in association with anaesthetic agents. A number of phenothiazines are now in use; some are preferred for one type of disorder, some for another. They have been classified according to their sedative, antimuscarinic and extrapyramidal effects (Box 20.1).

Box 20.1

Classification of phenothiazines

Group 1

• Chlorpromazine

• Levomepromazine (methotrimeprazine)

• Promazine

Sedation++++, antimuscarinic++, extrapyramidal++

Group 2

• Pericyazine

• Pipotiazine

• Thioridazine

Sedation++, antimuscarinic++++, extrapyramidal++

Group 3

• Fluphenazine

• Perphenazine

• Prochlorperazine

• Trifluoperazine

Sedation++, antimuscarinic++, extrapyramidal++++

Key:++=few to moderate effects,++++=marked effects.

The doses of these drugs are very variable and depend on the disorder being treated, and on the response and age of the patient. In long-term administration, it is not worth altering the dose more than once a week, because of their variable and prolonged actions.

In treating psychotic patients, large doses of phenothiazines are often used and may have to be continued for many months or even longer. This means that a careful watch must be kept for adverse effects, especially those involving the nervous system.

Adverse effects of phenothiazines

Adverse effects with phenothiazines are not uncommon and the incidence varies from drug to drug. They include:

• Jaundice. This occurs with chlorpromazine and is due to blocking of the bile canaliculi in the liver. It is presumed to be an allergic effect, and recovery occurs when the drug is stopped.

• Various disorders of movement, due directly or indirectly to a dopamine-blocking action in the brain. These may occur with all neuroleptics:

Parkinsonism.

Akathisia, which is a feeling of restlessness with an inability to stand still.

Tardive dyskinesia, consisting of abnormal movements of the mouth and tongue and sometimes the upper limbs. It develops in about 20% of patients on longer-term neuroleptics. Its onset is usually delayed for a while. Control is difficult and it may not stop even if the drug is withdrawn.

All these symptoms may commence soon after starting treatment and require a reduction of the dose if possible. Akathisia may be helped by a benzodiazepine; anticholinergic drugs such as benztropine may help the dystonic reaction and parkinsonism.

• Depressed leucocyte count.

• Skin rashes, including light sensitivity and contact dermatitis when the drug is handled. A sunscreen is advised with chloropromazine.

• An α– blocking effect on the sympathetic nervous system, leading to a fall in blood pressure and faintness.

• Hypothermia in elderly patients.

• Weight gain and the development of gynaecomastia (breast development in men) and male impotence.

• Dry mouth can be troublesome.

• Sedation, which is greatest with chlorpromazine.

• Rarely, the neuroleptic malignant syndrome with hyperpyrexia, coma and muscular rigidity may develop; this requires urgent treatment.

Thioridazine is a particularly effective drug, especially for treating schizophrenia, but is associated with considerable cardiotoxicity, in particular an increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias. The Committee for the Safety of Medicines has recommended that thioridazine be prescribed only for adults suffering from schizophrenia under specialist supervision. It is contraindicated in patients with cardiovascular disease who have a history of ventricular arrhythmias, Q–T interval prolongation or reduced cytochrome P450 2D6 activity. This drug should be prescribed only when under the supervision of a specialist and even then with extreme caution. Patients should be monitored closely, especially for cardiovascular symptoms.

With the present state of knowledge, it is impossible to say which is the best drug of this group. Patients seem to vary in their response to individual drugs and trial and error seems to be the only way to decide which is the best for any particular patient.

The thioxanthenes

These are rather similar to the phenothiazines. They are antipsychotic and antiemetic and are largely used in the treatment of schizophrenia. They are less sedative than the phenothiazines, but akathisia is rather common. An example is flupentixol, which is used as an injected depot preparation every 2 weeks, or daily as tablets.

The butyrophenones

This group of drugs has actions rather similar to those of the phenothiazines. They are less sedative, but are liable to produce extrapyramidal (parkinsonism-like) side-effects. Haloperidol is particularly useful in the management of manic or confused patients. Droperidol is similar but acts more rapidly.

Other neuroleptics

Pimozide is an antipsychotic drug used in the treatment of schizophrenia and manic states. It is longer-acting and less sedative than chlorpromazine. Pimozide can cause adverse effects such as dangerous cardiac arrhythmias and should not be given to those who suffer from them. An ECG should be taken before starting treatment and repeated at 6-monthly intervals for those receiving high doses.

Sulpiride has a more specific dopamine-blocking action than the other neuroleptics but with less adverse effects. However, it can still cause various disorders of movement, and is also associated with hepatitis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access