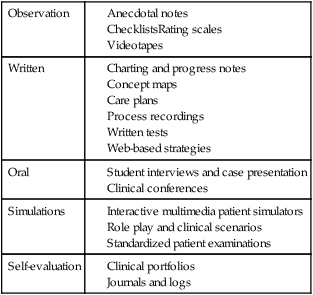

When clinical performance is evaluated, students’ skills are judged as they relate to an established standard of patient care. Acceptable clinical performance involves behavior, knowledge, and attitudes that students gradually develop in a variety of settings (Caldwell & Tenofsky, 1996). The ultimate outcome for clinical performance evaluation is safe, quality patient care. Clinical performance evaluation provides information to the student about performance and provides data that may be used for individual student development, assigning grades, and making decisions about the curriculum. Students have the right to a reliable and valid evaluation that assesses achievement of competencies required to take on the role of the novice nurse (Redman, Lenberg, & Walker, 1999). Box 27-1 provides some “quick tips” to be considered at the beginning of the evaluation process. Good practice includes multidimensional evaluation with diverse evaluation methods completed over time, seeking student growth and progress. All evaluation should respect students’ dignity and self-esteem. In addition to the concept of assessment, grading is considered part of a systems approach that includes integrating grading as a component of learning (Walvoord, Anderson, & Angelo, 2010). Faculty have primary responsibility for the student clinical evaluation. Faculty are knowledgeable about the purpose of the evaluation and the objectives that will be used to judge each student’s performance. This clarity of purpose provides direction for selection of evaluation tools and processes. Initial faculty challenges in completing clinical evaluations include factors such as faculty value systems, the number of students supervised, and reasonable clinical opportunities for students. Clinical evaluation is complex, with different students having different learning experiences (Walsh & Seldomridge, 2005). Faculty need to be aware of their own value systems to avoid biasing the evaluation process. When faculty are supervising a group of students in the delivery of safe and appropriate nursing care, faculty can only sample student behaviors. Limited sampling of behaviors or individual biases may result in an inaccurate or unfair clinical evaluation (Orchard, 1994). Because of these limitations, faculty use a variety of evaluation methods to capture the broader picture of student competence. Faculty strive to identify equitable assignments and can consider evaluation input from other sources with potential adjunct evaluators, including students, nursing staff and preceptors, peer evaluators, and patients. Completion of self-assessments by students provides not only data, as part of the evaluation process, but also a learning experience for the students (Bonnel, 2008; Loving, 1993). Student self-evaluation provides a starting point for reviewing, comparing, and discussing evaluative data with faculty. Initial student involvement in self-assessment tends to facilitate student behavior changes and provides a positive environment for learning and improvement. Participation in their own evaluation also empowers students to make choices and identify their strengths. Self-assessments are further discussed later in this chapter as a component of self-evaluation and self-reflection. Preceptors have a specified role in modeling and facilitating clinical education for students, especially for advanced nursing students. Typically preceptors serve a more formal role in evaluation, such as an adjunct faculty role, and provide evaluative data as part of a faculty team. If staff nurses and nurse preceptors provide data for the evaluation process, they should be oriented to the nursing school’s evaluation plan. Roles should be clarified, indicating whether staff will be asked to provide occasional comments, to report only incidents or concerns, or to complete a specific evaluation form. Hrobsky and Kersbergen (2002) describe the use of a clinical map to assist preceptors in identifying student strengths and weaknesses. Seldomridge and Walsh (2006) note the importance of adequately preparing adjunct evaluators for their role, teaching these individuals to provide good feedback with tools such as rubrics to promote consistency and specifying clinical activities to evaluate. There is debate about the appropriateness of having student peers act as evaluators in the clinical setting. Student peers should only evaluate competencies and assignments that they are prepared to judge. There should be clear guidelines for peer review and the student levels of responsibility (McAllister & Osborne, 1997). Peer evaluation can help students develop collaborative skills, build communication abilities, and promote professional responsibility. A potential disadvantage is that peers may be biased in providing only favorable information about student colleagues or may have unrealistic expectations of their student colleagues. Providing students with this peer evaluation opportunity and then appropriately weighting the contribution can be a reasonable practice (Boehm & Bonnel, 2010). Appropriate timing of evaluation and student feedback should be considered. Formative evaluation focuses on the process of student development during the clinical activity, whereas summative evaluation comes at the conclusion of a specified clinical activity to determine student accomplishment. Formative evaluation can assist in diagnosing student problems and learning needs. Appropriate feedback enables students to learn from their mistakes and allows for growth and improvement in behavior. Summative evaluation attests to competency attainment or meeting of objectives. Each of these concepts has unique contributions to the evaluation process, which is discussed further in Chapter 24. There are both ethical and legal issues relevant to privacy of evaluation data that can affect the student, faculty, and institution. Before conducting clinical evaluations, the educator must determine who will have access to data. In most cases, detailed evaluative data are shared only between the faculty member and the individual student. Program policy should identify who additionally may have access to the evaluation and how evaluative information will be stored and for how long. Evaluative data should be stored in a secure area. As designated by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), students 18 years of age or older or in postsecondary schools have the right to inspect records maintained by a school (U.S. Department of Education, 1974). A school’s program materials such as catalogues and handbooks can be tools to ensure the creation of reasonable and prudent policies that are in compliance with legal and accrediting guidelines. Privacy of written anecdotal notes and computer documents or personal digital assistant (PDA) notes also need to be maintained. Additionally, anecdotal notes should be objectively written as they have potential to be subpoenaed in legal proceedings. Inadequate security of this information could lead to a breach of student privacy. Challenges may also exist in evaluating students’ use of electronic health records. While protecting health information privacy for patients, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) may create problems for faculty and students in accessing written clinical data. Since electronic health records are an important component of student learning, faculty need to be familiar with the guidelines and procedures that clinical agencies have developed for students and faculty to access needed patient care documents. Students and faculty may be provided codes, for example, to access electronic data needed for patient care. If clinical access to electronic health records is limited, another way to evaluate the student’s ability is to provide simulations using those commercial products designed to teach about the electronic health record. Additional legal considerations are discussed in Chapter 3. Many methods and tools are used to measure learning in the clinical setting. A variety of approaches should be incorporated in clinical evaluation, including cognitive, psychomotor, and affective considerations as well as cultural competence and ethical decision making (Gaberson & Oermann, 2010). Additionally, educators cannot ignore the social connotations of grading, including the impact that evaluation has on the learning process and student motivation (Wiles & Bishop, 2001). The goal of evaluation is an objective report about the quality of the clinical performance. Faculty need to be aware that potential exists for evaluation of students’ clinical performance to be subjective and inconsistent. Even with “objective” instruments based on measurable and observable behavior, subjectivity can still be introduced into a tool that is viewed as objective. Reilly and Oermann (1992) encourage faculty to be sensitive to the forces that contribute to the subjective side of evaluation as they strive for fairness and consistency. Fair and reasonable evaluation of students in clinical settings requires use of appropriate evaluation tools that are ideally efficient for faculty to use. Any evaluation instrument used to measure clinical learning and performance should have criteria that are consistent with course objectives and the teaching institution’s purpose and philosophy. Attention to student clinical progress, not only across semesters but across a program, can be considered with similar, consistent evaluation processes and tools that progress across the program (Bonnel & Smith, 2010). Primary strategies for the evaluation of clinical practice include (1) observation, (2) written communication, (3) oral communication, (4) simulation, and (5) self-evaluation. Because clinical practice is complex, a combination of methods used over time is indicated and helps support a fair and reasonable evaluation. See Table 27-1 for a summary of common strategies and clinical evaluation tools by category. These are also discussed in the following paragraphs. TABLE 27-1 Sample Evaluation Strategies and Tools by Category Observation is the method used most frequently in clinical performance evaluation. Student performance is compared to clinical competency expectations as designated in course objectives. Faculty observe and analyze the performance, provide feedback on the observation, and determine whether further instruction is needed. A large national survey specific to faculty clinical evaluation and grading practices confirmed the predominance of observation (Oermann, Yarbrough, Saewert, Ard, & Charasika, 2009). Authors noted that continuing issues in clinical evaluation include wide variability in clinical environments, increasingly complex patients, and more diverse students. Real-time observation and delayed video observation are both considered in this discussion. Technology or online cases also provide unique opportunities for enhancing evaluation opportunities and standardization of evaluations. Newer approaches to use of videos in evaluation include online tools such as the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale training. In this example, video cases were developed based on needed competencies for appropriate use of the Stroke Scale. Students complete testing specific to these competencies as they refer to the online video cases (NIH Stroke Scale, n.d.). This provides a standardized testing approach. Advantages of observation include the potential for direct visualization and confirmation of student performance, but observation can also be challenging. Sample factors that can interfere with observations include lack of specificity of the particular behaviors to be observed; an inadequate sampling of behaviors from which to draw conclusions about a student’s performance; and the evaluator’s own influences and perceptions, which can affect judgment of the observed performance (Reilly & Oermann, 1992). An abundance of information must be tracked in clinical observation. Faculty can benefit from systems to help document and organize this information. Faculty can carry copies of evaluation tools and anecdotal records or can consider the use of a PDA to help facilitate retrieval and use of clinical evaluation records. While a variety of strategies for using PDAs in the clinical setting exist, a particular example is inclusion of anecdotal records and student “check-offs” in the memo function of the PDA (Lehman, 2003). Privacy in PDA records is also needed. Anecdotal or progress notes are objective written descriptions of observed student performance or behaviors. The format for these can vary from loosely structured “plus–minus” observation notes to structured lists of observations in relation to specified clinical objectives. These written notes initially serve as part of formative evaluation. As student performance records are documented over time, a pattern is established. This record or pattern of information pertaining to the student and specific clinical behaviors helps document the student’s performance pattern for both summative evaluation and recall during student–faculty conference sessions. Liberto, Roncher, and Shellenbarger (1999) noted the importance of determining which clinical incidents to assess and the need to identify both positive and negative student behaviors. Checklists are lists of items or performance indicators requiring dichotomous responses such as satisfactory–unsatisfactory or pass–fail (Table 27-2). Gronlund (2005) describes a checklist as an inventory of measurable performance dimensions or products with a place to record a simple “yes” or “no” judgment. These short, easy-to-complete tools are frequently used for evaluating clinical performance. Checklists, such as nursing skills check-off lists, are useful for evaluation of specific well-defined behaviors and are commonly used in the clinical simulated laboratory setting. Rating scales, described in the following paragraph, provide more detail than checklists concerning the quality of a student’s performance. TABLE 27-2 Example of Checklist Items and Format Rating scales incorporate qualitative and quantitative judgments regarding the learner’s performance in the clinical setting (Box 27-2). A list of clinical behaviors or competencies is rated on a numerical scale such as a 5-point or 7-point scale with descriptors. These descriptors take the form of abstract labels (such as A, B, C, D, and E or 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1), frequency labels (e.g., always, usually, frequently, sometimes, and never), or qualitative labels (e.g., superior, above average, average, and below average). A rating scale provides the instructor with a convenient form on which to record judgments indicating the degree of student performance. This differs from a checklist in that it allows for more discrimination in judging behaviors as compared with dichotomous “yes” and “no” options. Mahara (1998) noted the benefit of more standardized assessments such as checklists and rating scales but faults these objective scales for failing to capture the complex clinical practice environment and clinical learning. Oermann (1997) emphasized the benefit of asking appropriate patient care questions along with clinical observations to gauge student critical thinking abilities. Rubrics, a type of rating scale, help convey clinically related assignment expectations to students. They provide clear direction for graders and promote reliability among multiple graders. The detail provided in a rubric grid allows faculty to provide rapid and extensive feedback to students without extensive writing (Walvoord et al., 2010). Typical parts to a rubric include the task or assignment description and some type of scale, breakdown of assignment parts, and descriptor of each performance level (Stevens & Levi, 2005). Rubric examples exist for providing detailed feedback for clinical related assignments such as written clinical plans and conference participation. A web search by topic can provide samples for review. Rubrics or checklists are beneficial in facilitating both the lab experience and the clinical grading for faculty and students. They promote clear communication as to expectations of best practice in completing skills. Providing skills checklists for students provides direction in their skill learning and practice. Students can use these tools for self-assessments and participate in peer assessments to promote learning. Rubrics can be used within learning management systems as well. These tools can be distributed to students, as well as be completed by faculty, and tracked or monitored over time (Bonnel & Smith, 2010). Another method of recording observations of a student’s clinical performance is through videos. Videos, often completed in a simulated setting, can be used to record and evaluate specific performance behaviors relevant to diverse clinical settings. Advantages associated with videos include their valuable start, stop, and replay capabilities, which allow an observation to be reviewed numerous times. Videos can promote self-evaluation, allowing students to see themselves and evaluate their performance more objectively. Videos also give teachers and students the opportunity to review the performance and provide feedback in determining whether further practice is indicated. Use of videos can contribute to the learning and growth of an entire clinical group when knowledge and feedback are shared (Reilly & Oermann, 1992). Videos are particularly popular for evaluation in distance learning situations. Videos can also be used with rating scales, checklists, or anecdotal records to organize and report behaviors observed on the videos. Use of written communication, whether paper-based or electronic, enables the faculty to evaluate clinical performance through assessing students’ abilities to translate what they have learned to the written word. Review of student nursing care plans or written notes allows faculty to evaluate students’ abilities to communicate with other care providers. Through writing assignments, students can clarify and organize their thoughts (Cowles, Strickland, & Rodgers, 2001). Additionally, writing can reinforce new knowledge and expand thinking on a topic. Faculty evaluation focuses on the quality of the content and student ability to communicate information and ideas in written form. The rater can determine the student’s perspectives and gain insight into the “why” of the student’s behavior. A scoring tool such as a rubric with specified objectives for a designated assignment can promote consistency and efficiency in grading specified assignments (Stevens & Levi, 2005). Written data help support faculty clinical observations. The value of electronic text-based communication in the changing health care system is evident. Writing cogent nursing and clinical progress notes is an important clinical skill. Reviewing student documentation provides faculty with an opportunity to evaluate students’ ability to process and record relevant data. Students’ skill in using health care terminology and documentation practices can be examined and critical thinking processes can be demonstrated in these notes (Higuchi & Donald, 2002). With the focus on electronic records as a tool in patient safety, orienting students to these tools and evaluating students’ skill in this area is essential (Bonnel & Smith, 2010).

Clinical performance evaluation

General issues in assessment of clinical performance

Participants in evaluation

Faculty

Students

Nursing staff and preceptors

Peer evaluators

Evaluation timing

Evaluation access and privacy considerations

Clinical evaluation methods and tools

Observation

Written

Oral

Simulations

Self-evaluation

Evaluation strategies: observation

Tracking clinical observation evaluation data

Anecdotal notes

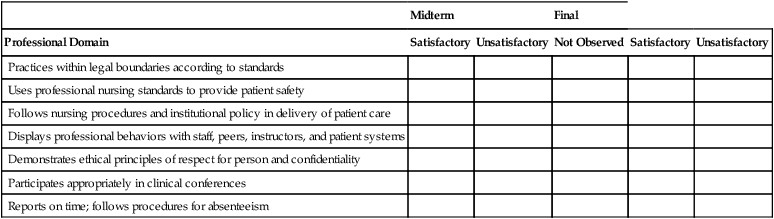

Checklists

Midterm

Final

Professional Domain

Satisfactory

Unsatisfactory

Not Observed

Satisfactory

Unsatisfactory

Practices within legal boundaries according to standards

Uses professional nursing standards to provide patient safety

Follows nursing procedures and institutional policy in delivery of patient care

Displays professional behaviors with staff, peers, instructors, and patient systems

Demonstrates ethical principles of respect for person and confidentiality

Participates appropriately in clinical conferences

Reports on time; follows procedures for absenteeism

Rating scales and rubrics

Videotapes as source of observational data

Evaluation strategies: student written communication

Documentation and patient progress notes

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree