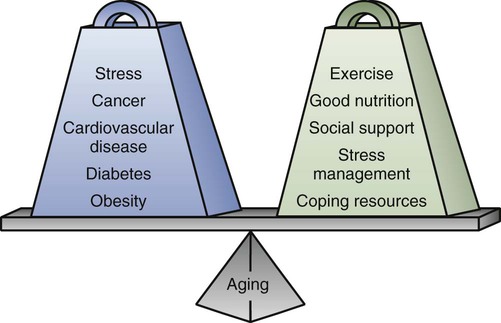

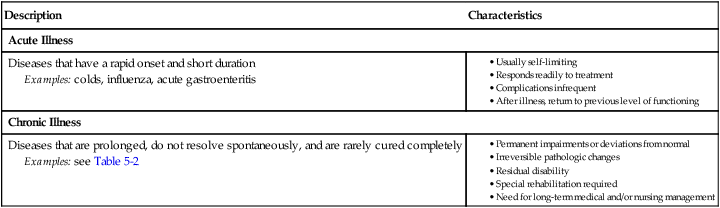

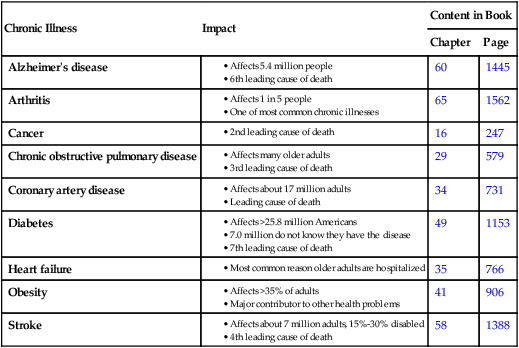

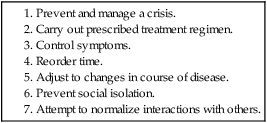

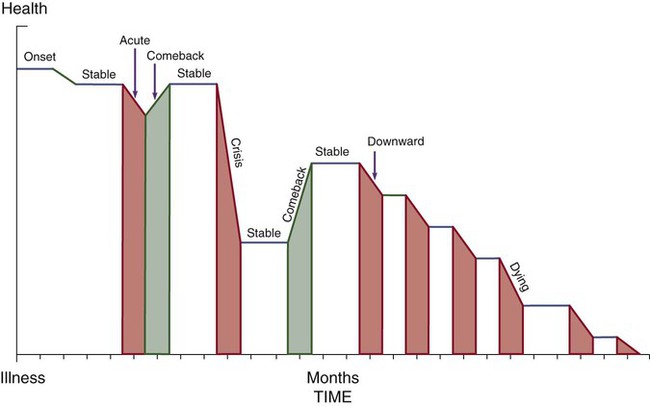

Margaret Baker and Margaret McLean Heitkemper 1. Describe the prevention and major causes of chronic illness. 2. Explain the characteristics of a chronic illness. 4. Explain the needs of special populations of older adults. 5. Describe nursing interventions to assist older adults with chronic conditions. 6. Describe common problems of older adults related to hospitalization and acute illness and the nurse’s role in assisting them. 7. Differentiate among care alternatives to meet needs of older adults. 8. Describe the nurse’s role in health promotion, disease prevention, and managing the special needs of older adults. Illness can be categorized as either acute or chronic (Table 5-1). Today the U.S. health care system faces a growing burden of chronic illness as the population ages. Chronic diseases account for 70% of all deaths in the United States.1 Chronic illness results in limitations in physical functioning, work productivity, and quality of life for nearly 1 out of 10 Americans, or about 31 million people. Older adults often live with more than one chronic illness. A significant portion of U.S. health care dollars go toward the treatment of chronic illnesses.1 The management of a chronic illness can profoundly affect the lives and identities of the patient, family, and caregiver. Table 5-2 presents the impact of some chronic illnesses. TABLE 5-1 CHARACTERISTICS OF ACUTE AND CHRONIC ILLNESS TABLE 5-2 Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Quick facts: economic and health burden of chronic disease. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/press/index.xhtml#3; and Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2011 update. eTABLE 5-1 GERIATRIC DEPRESSION SCALE (SHORT FORM) From The use of rating depression series in the elderly, in Poon LW, editor: Handbook for clinical memory assessment of older adults, Washington, DC, 1986, American Psychological Association. In addition to people living longer, other societal changes have contributed to the increase in chronic illnesses, including insufficient physical activity, lack of access to fresh fruits and vegetables, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption.1 Chronic illnesses may have acute exacerbations in which an individual moves from a level of optimum functioning, with the illness well controlled, to a period of instability during which the individual may need assistance. Corbin and Strauss proposed a view of chronic illness as a trajectory (Fig. 5-1) with overlapping phases2 (Table 5-3). This trajectory characterizes the common course of most chronic illnesses. In addition, Corbin and Strauss identified the seven tasks of those who are chronically ill2 (Table 5-4). These tasks are discussed in the following sections. TABLE 5-3 Source: Woog P: The chronic illness trajectory framework: the Corbin and Strauss nursing model, New York, 1992, Springer. TABLE 5-4 SEVEN TASKS OF PEOPLE WITH CHRONIC ILLNESS Source: Corbin JM, Strauss A: A nursing model for chronic illness management based upon the trajectory framework, Sch Inq Nurs Pract 5:155, 1991. Treatment regimens vary in degree of difficulty and the impact that they have on the person’s lifestyle. Characteristics of treatment regimens are included in Table 5-5. TABLE 5-5 CHARACTERISTICS OF TREATMENT REGIMENS Chronic illnesses are often preventable. Primary prevention refers to measures such as proper diet, proper exercise, and immunizations that prevent the occurrence of a specific disease. Secondary prevention refers to actions aimed at early detection of disease that can lead to interventions to prevent disease progression. Tertiary prevention refers to activities that limit disease progression, such as rehabilitation.3 Because the majority of chronic illnesses are treated in an ambulatory care setting, it is increasingly important for patients and caregivers to understand and manage their own health. The term self-management refers to the individual’s ability to manage his or her symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences, and lifestyle changes in response to living with a long-term disorder.4 Family caregivers (e.g., spouses, adult children, partners) often have important roles in the life of the chronically ill person. The ideal situation is one in which family caregivers work together with the patient to manage the illness. This collaboration begins under the direction of the health care team at the time of diagnosis. When the caregiver is a spouse who is also older, he or she may have a chronic illness as well, which complicates the situation.5 The stresses and needs of family caregivers are discussed in Chapter 4 and Table 4-5. In the past three decades the older adult population (those 65 years of age and older) has grown twice as fast as the rest of the population. Almost 40 million people, or 13% of the population, are age 65 or older.6 Nearly one in five U.S. residents is expected to be 65 or older by 2030. The number of Americans age 85 or older is expected to more than triple, from 5.8 million to 19 million, between 2010 and 2050.6 This dramatic increase is in part due to aging of the Baby Boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964) who began to turn 65 in 2011. Upcoming cohorts of older adults will be better educated than previous cohorts and have greater access to technology and resources. In the United States 13% of people over age 65 are people of color, including 8% African Americans; 3% Asian/Pacific Islanders; and less than 1% American Indians, Eskimos, and Aleuts. People of Hispanic/Latino ethnicity (who may be of any race) represent 7% of the older population.1 By 2030 the proportion of older adults who are people of color will increase 160% (Latinos 202%; African Americans 114%; American Indians, Eskimos, and Aleuts 145%; and Asian/Pacific Islanders 145%), while growth in the European-American population will increase by only 59%.6 The U.S. Census Bureau predicts life expectancy to continue to increase for both men and women. Men and women born in 1950 who reach age 65 can expect, on average, another 12.8 and 15.8 years of life, respectively.1,7 Whether this gender difference is due to differences in health behaviors (e.g., smoking, alcohol use) or occupation is not known.8 Nearly 6% of individuals age 65 to 74 and 25% of those 85 and older live in nursing homes.8 The frail older adult is usually over age 75 and has physical, cognitive, or mental dysfunctions that may interfere with independently performing ADLs.9 (Older frail adults are discussed later in this chapter.) Who is old? The answer to this question often depends on the respondent’s age and attitude. It is important to understand that aging is normal and is not related to pathology or disease. Age is established by a date in time and is influenced by many factors, including emotional and physical health, developmental stage, socioeconomic status, culture, and ethnicity.10 Myths and stereotypes about aging are often supported by media reports of older adults who are “problematic.” These commonly held misconceptions may lead to errors in assessment and unnecessary limitations or interventions. For example, if you think that all older people are rigid in their thinking, you may not present new ideas to a patient.11 Ageism is a negative attitude based on age. Ageism leads to discrimination and disparities in the care given to older adults. If you demonstrate negative attitudes, it may be because you fear your own aging process or you are not knowledgeable about aging and the health care needs of the older adult. Therefore it is important to gain knowledge about normal aging and have increased contact with older adults who are healthy and live independently. Also, it is your role as a nurse to dispel myths of aging. From a biologic view, aging is defined as the progressive loss of function. The exact cause of biologic aging is unknown. Biologic aging is a multifactorial process involving genetics, diet, and environment.12 In part, biologic aging can be viewed as a balance of positive and negative factors (Fig. 5-2). Research is directed at increasing both the average life span and the quality of life of older adults. The hope is that new antiaging therapies will be developed to slow down or reverse age-related changes that result in chronic illness and disability. Based on numerous laboratory studies in rodents, caloric restriction (reducing dietary intake by 25% to 50%) has been consistently shown to significantly extend the life span.13 It may be that caloric restriction results in changes in body composition, metabolism, and hormones that are conducive to long life. Caloric restriction in humans is associated with decreases in the incidence of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cancer, all of which are associated with aging.13,14 A number of nutrients have been tested for their potential benefits in reducing the impact of aging. Examples include β-carotene, selenium, vitamin C, and vitamin E. To date, research has failed to show that large doses of these supplements prevent chronic illness, such as heart disease or diabetes.15 However, much more research is needed before it is determined whether any of these substances will delay aging or enhance the functional ability of older adults. Age-related changes affect every body system. These changes are normal and occur as people age. However, the age at which specific changes occur differs from person to person and within the same person. For instance, a person may have gray hair at age 45 but relatively unwrinkled skin at age 80. In your role as a nurse, assess for age-related changes. Table 5-6 presents a list of tables where specific age-related assessment findings can be found throughout the book. TABLE 5-6 GERONTOLOGIC ASSESSMENT DIFFERENCES

Chronic Illness and Older Adults

Chronic Illness

Description

Characteristics

Acute Illness

Diseases that have a rapid onset and short duration

Examples: colds, influenza, acute gastroenteritis

Chronic Illness

Diseases that are prolonged, do not resolve spontaneously, and are rarely cured completely

Examples: see Table 5-2

Chronic Illness

Impact

Content in Book

Chapter

Page

Alzheimer’s disease

60

1445

Arthritis

65

1562

Cancer

16

247

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

29

579

Coronary artery disease

34

731

Diabetes

49

1153

Heart failure

35

766

Obesity

41

906

Stroke

58

1388

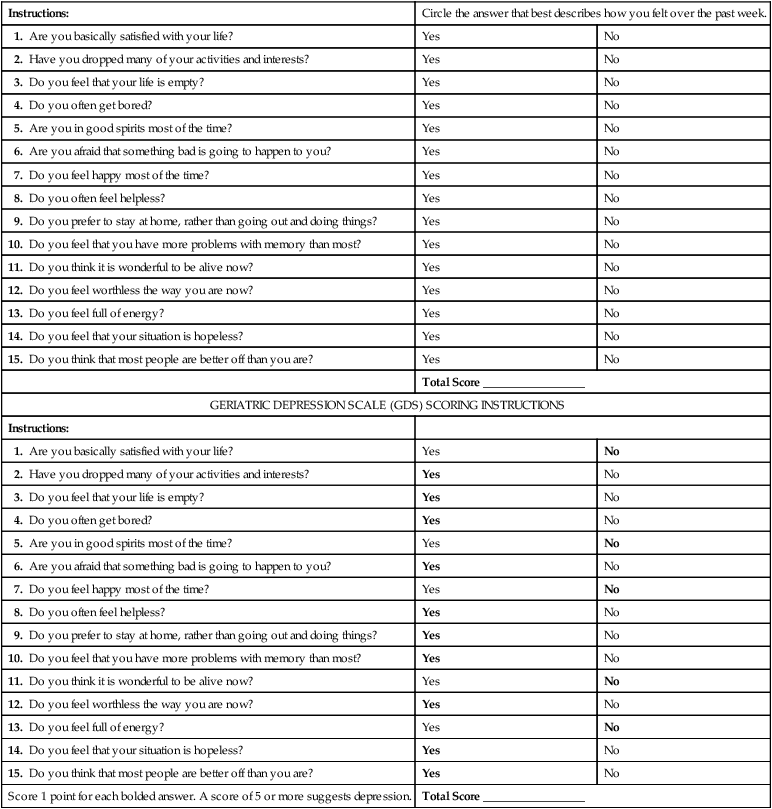

Instructions:

Circle the answer that best describes how you felt over the past week.

1. Are you basically satisfied with your life?

Yes

No

2. Have you dropped many of your activities and interests?

Yes

No

3. Do you feel that your life is empty?

Yes

No

4. Do you often get bored?

Yes

No

5. Are you in good spirits most of the time?

Yes

No

6. Are you afraid that something bad is going to happen to you?

Yes

No

7. Do you feel happy most of the time?

Yes

No

8. Do you often feel helpless?

Yes

No

9. Do you prefer to stay at home, rather than going out and doing things?

Yes

No

10. Do you feel that you have more problems with memory than most?

Yes

No

11. Do you think it is wonderful to be alive now?

Yes

No

12. Do you feel worthless the way you are now?

Yes

No

13. Do you feel full of energy?

Yes

No

14. Do you feel that your situation is hopeless?

Yes

No

15. Do you think that most people are better off than you are?

Yes

No

Total Score _________________

GERIATRIC DEPRESSION SCALE (GDS) SCORING INSTRUCTIONS

Instructions:

1. Are you basically satisfied with your life?

Yes

No

2. Have you dropped many of your activities and interests?

Yes

No

3. Do you feel that your life is empty?

Yes

No

4. Do you often get bored?

Yes

No

5. Are you in good spirits most of the time?

Yes

No

6. Are you afraid that something bad is going to happen to you?

Yes

No

7. Do you feel happy most of the time?

Yes

No

8. Do you often feel helpless?

Yes

No

9. Do you prefer to stay at home, rather than going out and doing things?

Yes

No

10. Do you feel that you have more problems with memory than most?

Yes

No

11. Do you think it is wonderful to be alive now?

Yes

No

12. Do you feel worthless the way you are now?

Yes

No

13. Do you feel full of energy?

Yes

No

14. Do you feel that your situation is hopeless?

Yes

No

15. Do you think that most people are better off than you are?

Yes

No

Score 1 point for each bolded answer. A score of 5 or more suggests depression.

Total Score _________________

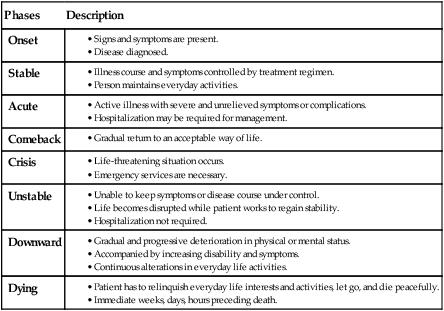

Trajectory of Chronic Illness

Phases

Description

Onset

Stable

Acute

Comeback

Crisis

Unstable

Downward

Dying

Carrying Out Prescribed Treatment Regimens.

Characteristic

Example

Difficult

Managing a home hemodialysis unit

Time consuming

Dressing changes done four times daily

Painful or uncomfortable

Injecting heparin daily in the abdomen

Unsightly appearance

Tracheostomy

Slow rate of effectiveness

Lowering blood cholesterol level with medication or diet

Prevention of Chronic Illness

Nursing Management Chronic Illness

Older Adults

Demographics of Aging

Attitudes Toward Aging

Biologic Aging

Age-Related Physiologic Changes

Summary of Tables

Body System

Table Number

Page

Visual

21-1

371

Auditory

21-7

380

Integumentary

23-1

417

Respiratory

26-4

481

Hematologic

30-3

619

Cardiovascular

32-1

691

Gastrointestinal

39-5

871

Urinary

45-2

1051

Endocrine

48-3

1141

Reproductive

51-3

1225

Nervous

56-4

1344

Musculoskeletal

62-1

1494 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Chronic Illness and Older Adults

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access