Chapter 18. Children and surgery

Linda Shields and Ann Tanner

ABSTRACT

The striking difference in nursing children, as opposed to adults, through a surgical experience is that they do not come alone but are an integral part of a family group, with parents and/or caregivers as advocates for their treatment, and often siblings and other relatives in their extended family (Alsop-Shields, 2000 and Smith and Dearmun, 2006). As such, their care is more complicated and involved than it would be for a consenting adult patient. Parents of children admitted to hospital for surgery often have high levels of anxiety. If this anxiety is transmitted to the child, it can have a negative impact on the child’s admission and surgery (Sadhasivam et al 2009). Increased availability of preoperative information, in the form of written information sheets, coupled with the exchange of information by nursing and medical staff is likely to reduce parental anxiety. Children undergoing surgery are often anxious. This anxiety may initiate a stress response, which can delay wound healing and suppress the immune system (Koinig 2002). Reduction of anxiety for the child and their parent is an important role for the perioperative nurse.

LEARNING OUTCOMES

• Gain an overview of the nature of paediatric surgery.

• Understand the role of parents and family-centred care in paediatric surgery.

• Gain an overview of common paediatric procedures of different age groups and developmental stages.

• Understand the importance of education for parents and children throughout any surgical experience.

• Understand the ethical and legal ramifications of surgery on children.

• Recognise and understand common paediatric emergencies.

• Understand the flow through the operating theatres: preparation, admission, induction, procedure/surgery/anaesthetic, recovery, discharge and education.

Why children need surgery

Paediatric surgery was not considered a specialised area separate to adult surgery until the first half of the 20th century (Mooney 1997). It encompasses a wide range of surgical procedures and differing ages, from premature infants weighing as little as 500–600 g to adolescents. There are many reasons why children need surgery. These can range from congenital malformations to accidental and non-accidental injuries, or a variety of disease processes (Shields & Werder 2002). A number of characteristic conditions and/or injuries for the varying age groups have been detailed in Table 18.1. These are representative of the general trends and are not indicative of all age groups or all types of surgery. Those highlighted have an accompanying photograph and a description of surgery.

| Age | Type of surgery | Figures |

|---|---|---|

| 0–2 | Hernia repair (most common-inguinal) | 18.1 |

| Repair of tracheo-oesphageal fistula | ||

| Diaphragmatic hernia repair | ||

| Repair of gastroschisis and exomphalos | Fig. 18.2, Fig. 18.3 and Fig. 18.4 | |

| Insertion of ventricular-peritoneal shunts for hydrocephalus | ||

| Circumcision (medical and cultural) | 18.5 | |

| Correction of congenital abnormalities (removal of extra digits, cleft palate repair, repair of imperforate anus) | ||

| Craniofacial surgery for congenital abnormalities such as fusion of cranial sutures | 18.6 | |

| Hypospadias repair | 18.8 | |

| Eye surgery such as probing of tear ducts and examination under anaesthetic for tumours | ||

| 2–5 | Common ENT procedures such as: | |

• insertion of grommets | ||

• adenoidectomy | 18.9 | |

• tonsillectomy | Fig. 18.10 and Fig. 18.11 | |

| Urological surgery such as cystoscopy and ureteric reimplantation | ||

| Lacerations, dog bites | ||

| Repair of fractured limbs | ||

| Dental restorations and extractions for multiple dental caries | ||

| Eye surgery for squint repair | ||

| Burns grafts for scald burns | ||

| Brain tumours | ||

| 5–10 | ENT: adenoidectomy, tonsillectomy | Fig. 18.10 and Fig. 18.11 |

| Repair of fractured limbs | ||

| Accidental injuries | ||

| Appendicectomy | 18.12 | |

| Orthopaedic surgery for congenital skeletal deformities | ||

| Brain tumours | ||

| 10–15 | Accidental injuries | |

| Lacerations | ||

| Repair of fractured limbs | ||

| Torsion of testes | ||

| Laparoscopic appendicectomy | 18.12 | |

| Bone tumours | ||

| Burns, grafts for flame burns |

Hernia repair

Hernias are one of the most common congenital abnormalities found in infants (Fig. 18.1). There are several different types of hernia affecting both male and female children. The most frequently occurring hernias are indirect and direct inguinal hernias and hydroceles. Hernias occur when the processus vaginalis (a peritoneal diverticulum that extends through the inguinal ring) remains as a patent conduit with the peritoneal cavity instead of closing off and disappearing. During fetal development, the processus vaginalis attaches itself to the testes and is pulled down into the scrotum as the testes descend. If the processus vaginalis remains patent it is a potential hernia. Twenty per cent of individuals have a patent processus but remain asymptomatic. If bowel or other contents from the abdomen enter the processus it becomes an actual hernia. If only peritoneal fluid enters the processus it becomes a communicating hydrocele (Weber & Tracy 2000). During male hernia repair, the hernial sac is dissected from the testicular structures; this dissection contains the risk of injury to the testicular blood flow (Palabiyik 2009).

|

| Fig. 18.1 Inguinal hernia in a child. |

Gastroschisis

Gastroschisis and omphalocele are two varieties of congenital abdominal wall defects resulting in a herniation of the abdominal contents in the developing fetus (Fig. 18.2). In gastroschisis the defect usually lies laterally to the umbilicus; the small and large bowel and often the stomach herniate through the defect and are not protected by a peritoneal membrane, but float freely within the amniotic fluid (Holcomb & Wallace 2000). The amniotic fluid acts as an irritant to the surface of the bowel, which forms a thick skin on the bowel surface. In an omphalocele, the umbilical ring is defective and can include a herniation of the entire small and large bowel, the stomach and the liver. Omphaloceles are protected by a layer of the peritoneal membrane. Atresia of the bowel can occur if the opening of the defect is narrow and the blood supply to the bowel has been compromised due to the subsequent stricture. For atresia, the affected bowel is resected. If the infant loses excess intestinal length – ‘short gut syndrome’, which impairs reabsorption of sufficient fluids and nutrients – the child may be dependent on total parenteral nutrition for life.

|

| Fig. 18.2 Gastroschisis. |

Treatment of gastroschisis depends on the size of the defect and the degree of herniation that has occurred. Elective caesarian of an infant with a known gastroschisis can limit the increased morbidity which may occur with prolonged labour and vaginal delivery (White 2009). Infants born with gastroschisis and omphalocele usually have surgery within the first day of life. Smaller defects may be manually reduced and the defect sutured as a primary closure. Larger defects may have a silo bag applied (Fig. 18.3), which contains all the abdominal contents. The bag hangs suspended above the infant and gravity and time aid in reducing the inflammation of the bowel, making it easier to manually reduce the hernia in a series of stages. If the abdominal wall defect is large, a prolene mesh graft may be used to assist in the closure of the defect. The defect can take years to close completely (Fig. 18.4).

|

| Fig. 18.3 Repair of gastroschisis. |

|

| Fig. 18.4 Child with healed gastroschisis at age 3. |

Circumcision

Circumcision was once routinely performed at birth in many countries, although this custom has now mostly disappeared. However, it remains a reasonably common procedure, although it is now performed for cultural/religious and medical reasons. There is some controversy surrounding male circumcision. In the UK about one-quarter of patients are circumcised for religious reasons (Mukherjee 2009). Medical circumcisions are required for two main conditions: phimosis, which is an inability to retract the foreskin, indicated by a ballooning of the foreskin on urination (Raynor 2000) and paraphimosis, which occurs when the foreskin which has retracted cannot be pulled back down, leaving it forming a stricture around the head of the penis.

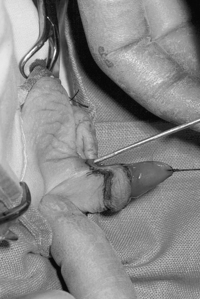

Circumcision is usually performed under general anaesthetic and a penile nerve block. The surgeon makes a blunt dissection between the glans and the foreskin, the collar of the foreskin that has been isolated is then excised usually using diathermy, and the shaft skin is then sutured to the subcoronal skin using interrupted absorbable sutures (Fig. 18.5).

|

| Fig. 18.5 Circumcision. |

Craniofacial surgery

One of the more frequent types of craniofacial surgery is cranial vault remodelling for the correction of fused cranial sutures (Herron et al 2002). These children require surgery at around 6 months of age. It is preferable to operate this young because the bones are relatively malleable and the fusion of cranial sutures has not yet caused any brain damage. The child is positioned either prone or supine, depending on the skull shape and the region of deformity.

Cranial vault remodelling involves a neurosurgeon and a plastic surgeon. A large hemicircular incision is made, within the hairline, from ear to ear. The scalp is retracted and periosteal elevators are used to scrape tissue off the periosteum (Fig. 18.6) in preparation for the craniotomy. The neurosurgeon performs the craniotomy (removal of the top half of the skull) and sutures any parts of the dura mater that might have been damaged during the removal. The plastic surgeon refashions the removed skull using bone cutters to make vertical cuts 3–5 cm in length into the skull around its circumference to widen and enlarge the skull. The refashioned skull is either wired or plated back onto the child’s head, and the scalp sutured back into place. In the instance of craniofacial deformities such as traumatic injury, biomaterials such as cement pastes, osteoactive biomaterials and prefabricated polymers are increasingly used. There is not the risk of donor site morbidity and they are not affected by the long-term re-absorption which can occur with autogenous bone grafts (Chim & Gossain 2009). A head bundle dressing is applied and drains are occasionally required to prevent a build up of old blood and subsequent wound infection and break down.

|

| Fig. 18.6 Craniofacial surgery. |

Hypospadias and repair

Hypospadias is one of the most common congenital anomalies. It occurs in 1:200 to 1:300 live births. The aetiology of hypospadias has been linked to environmental influences. There has been an increase over the past 30 years of male reproductive abnormalities occurring alongside the increased production and use of synthetic chemicals. Concerns have been raised that such environmental factors may play a role in the aetiology of hypospadias, undescended testes and lowered sperm count (Baskin & Ebbers 2006). Hypospadias (Fig. 18.7) is a developmental abnormality in which the urethra opens onto the ventral surface of the penis. The opening can occur anywhere from glans to the scrotum (Murphy 2000) (Fig. 18.8). Surgical repair of hypospadias is often two-staged. The repair involves the formation of a flap using the meatus to create a neourethra that opens at the tip of the glans. An indwelling catheter is left in situ for 7–10 days postoperatively, or until the dressing is removed.

|

| Fig. 18.7 Hypospadias. |

|

| Fig. 18.8 Hypospadias repair. |

Adenoidectomy

Adenoidectomy is a common ENT procedure on children, particularly 2–5-year-olds. Some children in that age bracket have tonsils and adenoids so enlarged that they obstruct their breathing, particularly during sleep. Snoring is often an indicator. Paediatric sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep disorder are often associated with behavioural problems, poor school performance and decreased quality of life. Adenotonsillectomy resolves sleep disorder behaviours in 80% of children, and improves quality of life and behaviours (Mitchell 2008). General anaesthetic is given and the child lies supine, with a gel roll under the shoulders to tilt the head back (Herron et al 2002). The surgeon inserts a mouth gag, which both depresses the tongue and holds the jaw open. Two rods are used to support the gag in place and to keep the head in position (Fig. 18.9). An adenotome is used to scrape the adenoidal tissue from the adenoidal bed. Diathermy is not routinely used for adenoidectomy, rather haemostasis is obtained by firmly packing a swab into the adenoidal bed. This is removed after about 5 minutes and may be replaced with a fresh swab if bleeding persists. Adenoidal bleeding usually occurs if the adenoidal tissue has not been sufficiently scraped away, in this instance the surgeon may re-curette the tissue with the adenotome. Occasionally, suction diathermy is needed to cauterise any vessels that continue to bleed. Because Raytec® swabs are routinely packed into the adenoidal space for haemostasis, the scrub nurse’s count is very important, as a bloody Raytec® is difficult to see and may cause a serious airway obstruction if left undetected.

|

| Fig. 18.9 Adenoidectomy. |

Tonsillitis

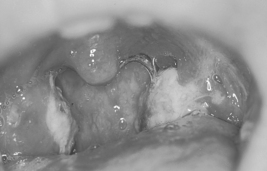

Tonsillitis is a common illness of childhood, an infection which produces a purulent discharge which covers the inflamed tonsils (Fig. 18.10) and is accompanied by fever and often extreme discomfort. There is some controversy over the need for tonsillectomy (Fig. 18.11) and adenoidectomy and there is some suggestion that the operations are performed unnecessarily in some instances (Montgomery 1996). In children, adenotonsillectomy or adenoidectomy are performed to treat recurrent tonsillitis, obstruction of the nasopharynx and obstructive sleep apnoea (Nieminen et al 2000). Traditionally, there have been two methods for tonsillectomy – using a tonsil snare (guillotine) which loops over the tonsil and cuts it off at its base (Homer et al 2000), and more recently, by sharp or blunt dissection (Meeker & Rothrock 1999). Despite newer technologies, tonsillectomy is still associated with a relatively high risk of postoperative morbidity such as pain and bleeding (Sergi & Younis 2007).

|

| Fig. 18.10 Tonsillitis. |

|

| Fig. 18.11 Patient prepared for tonsillectomy. |

Laparoscopic appendicectomy

Children presenting with acute appendicitis usually have a number of tell-tale signs and symptoms. The onset of acute appendicitis is usually over a period of 6–36 hours. The child complains of abdominal pain, which commences around the umbilical area but moves to the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. If the appendix is inflamed the child may be febrile. In appendicitis, vomiting usually begins after the onset of pain; if the child begins vomiting before the onset of pain then the prognosis is more likely to be gastritis (Ein 2000). Diarrhoea does not usually commence unless the appendix has perforated, in which the case the sigmoid colon becomes involved and peritonitis may ensue.

Ultrasound is often performed to confirm a suspected appendicitis. Laparoscopic appendicectomy (Fig. 18.12) offers faster recovery times and a reduced rate of wound infection compared with open appendicectomy (Paterson 2008), and is now the preferred method. It involves the insertion of a large port or trocar for the camera at the umbilicus, and one to two other ports (usually 5 mm wide) for the grasping instruments. The appendix is ligated away from the appendiceal mesentery using diathermy. Once freed, the appendix is tied off, dissected from the bowel and removed via a 10-mm port (which is inserted to replace one of the 5-mm ports) and routinely sent for pathology.

Activity

Activity

www

www

www

www

Activity

ActivitySearch the Cochrane Library for a copy of the protocol for the review about the use of topical anaesthetics for needle insertion in children (Kleiber et al 2002).

www

wwwVisit the Association for the Wellbeing of Children in Healthcare website to order their publications about parents in the operating theatre: Parental involvement in their child’s anaesthetic (video) and Policy relating to the provision of care for children undergoing anaesthesia:

www

wwwVisit the Action for Sick Children website and see what information can be given to parents and children about going to the operating theatre:

|

| Fig. 18.12 Laparoscopic appendicectomy. |

The role of the family

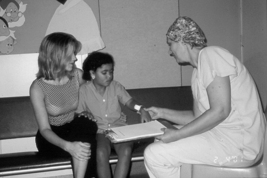

In times past, parents (the child’s natural parent, step-parent, legal guardian or carer) were excluded from the hospital during a child’s admission (Glasper and Charles-Edwards, 2002 and Jolley and Shields, 2008). Such attitudes are now not widespread and parents are encouraged, and often expected, to stay for the duration of the child’s admission. However, parental presence in the operating room is a more contentious issue.

Forty years ago, admission to hospital was portrayed as a positive, growth-promoting experience for children (Jessner et al., 1952 and Oremland and Oremland, 1973) and the experience of overcoming the emotional trauma associated with surgery was extolled as character-forming (Blom 1958); as late as 1992, Lansdown suggested that children could gain psychologically from a hospital admission. However, studies of the psychological trauma encountered by children and their parents before admission have highlighted the importance of adequate preparation of children for hospital admission and surgery (Strachan 1993).

Children have needs different to adults (Price 1994). The most important factor differentiating the needs of children from those of adults is their level of physical and psychological development.

A child’s eye view of the operating room

Children are smaller and less developed physically and emotionally than adults, so have different visual and psychological perspectives to adults. Consequently, the environment of the operating room looks different to a child (Fig. 18.13 and Fig. 18.14). Also, children lack the rationalisation skills that would allow them to integrate the environment perceptually, and so may become frightened.

|

| Fig. 18.13 A child’s view from the operating table. |

|

| Fig. 18.14 A child’s view of an anaesthetic mask. |

The paediatric operating room environment must be planned with this in mind and should be as ‘child-friendly’ as possible, with pictures and cartoons on the walls, bright curtains and hangings, and colourful mobiles. Children are small, so pictures on walls need to be at relevant heights, for example, the bottom of walls for children who walk into the operating room, and higher for children who arrive on a trolley. Toys, books, television and videotapes are needed, as the children often are not premedicated and play until taken into the theatre. If possible, and if the parent is adequately prepared, parents should stay with the child until the child is anaesthetised, either in an induction room or in the operating theatre itself. Toy cars are fun for children to ride in from the ward to the operating room, or trolleys dressed up as boats or other ‘fun’ vehicles. Operating room dress is often redundant for children and they can be admitted to the operating room in their own pyjamas or clothes (Fig. 18.15).

|

| Fig. 18.15 A child coming into the operating room in their own pyjamas. |

Ethics and the law in paediatric perioperative settings

Informed consent

Most hospitals have rigid, mandatory policies for obtaining consent for operation from a parent before their child’s surgery. It is imperative that the parents are fully informed as to the reason for the operation, what is going to happen to their child, and the risks involved (Steven et al 2008). By law in many countries, it is the duty of the surgeon to explain the procedure and accompanying risks (Perera 2008), and the anaesthetist has responsibility for explaining the anaesthetic and its implications to the patient before the operation (Australia, New Zealand College of Anaesthetists 2005). It is the nurses’ responsibility to ensure that the child (if able), and the parents have been told and that they understand what has been said (Daly 2009). This confirmation is done preoperatively by nurses on the ward, and by the nurse who receives the patient in the operating suite. In some hospitals, it is the admitting nurse in the operating suite who must check that the consent form has been signed; in others, the child cannot leave the ward for the operating room until the consent form is signed. Except in the most extreme emergency situations, no operation can begin without a signed consent form.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access