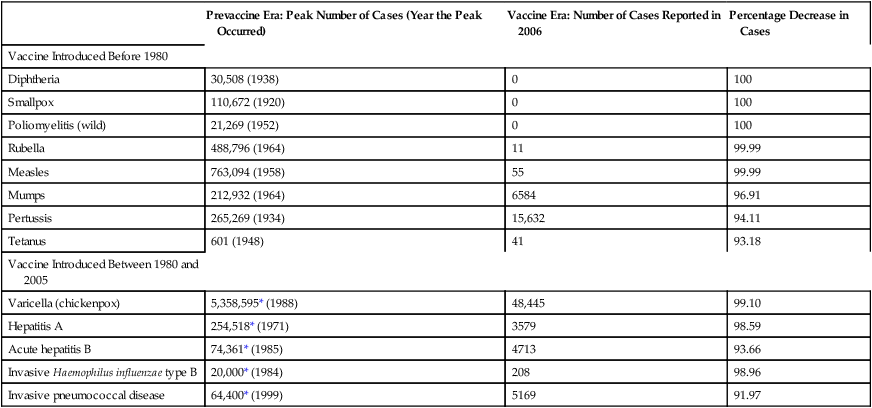

CHAPTER 68 In this chapter, discussion is limited to childhood immunization. Chapter 110 (Potential Weapons of Biologic, Radiologic, and Chemical Terrorism) addresses vaccines for anthrax and smallpox. And Chapter 93 (Antiviral Agents I: Drugs for Non-HIV Viral Infections) addresses a vaccine for avian flu. Widespread vaccination has had a profound impact on public health. In the United States, vaccination has greatly reduced the incidence of some infectious diseases (eg, pertussis, mumps, tetanus) and virtually eliminated five others: diphtheria, smallpox, poliomyelitis, rubella, and measles (Table 68–1). With two diseases, results have been even more dramatic: wild-type polio is gone from the Western hemisphere, and smallpox is gone from the planet. TABLE 68–1 Impact of Vaccination on the Incidence of Some Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in the United States Data from Roush SW, Murphy TV, and the Vaccine-Preventable Disease Table Working Group: Historical comparisons of morbidity and mortality for vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. JAMA 298:2155–2163, 2007. The risk of serious adverse reactions can be minimized by observing appropriate precautions and contraindications. Table 68–2 lists contraindications that apply to all vaccines. Precautions and contraindications that apply to specific vaccines are discussed in the context of those preparations. Certain conditions, such as diarrhea and mild illness, may be inappropriately regarded as contraindications by some practitioners. As a result, vaccination may be needlessly postponed. Conditions that are often considered contraindications, although they are not, are also listed in Table 68–2. TABLE 68–2 Practitioners are required to report certain adverse events to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). The information is used to help determine whether (1) a particular event that occurs after vaccination is actually caused by the vaccine, and (2) what the risk factors might be. In addition to reporting events that they are required to report, practitioners should report all other serious or unusual adverse events, regardless of whether they believe the event was caused by the vaccine. Forms for reporting adverse events can be obtained from the VAERS web site (www.vaers.hhs.gov) or by calling 1-800-822-7967. The National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act requires that Vaccine Information Statements (VISs) be given to all vaccinees (or their parents or legal representatives) before certain vaccines are administered. The VISs, produced by the CDC, are one-page, two-sided documents that describe the benefits and risks of specific vaccines. For vaccines that require a series of shots, a VIS must be given before each dose, not just the first dose. The VISs are available in over 30 languages, and can be obtained online at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/vis/default.htm. Each year, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), in cooperation with the American Academy of Family Physicians and the American Academy of Pediatrics, issues revised recommendations for childhood immunization in the United States. Figures 68–1 and 68–2 (see pp. 871–872) show the recommended schedule for 2011. You can find the catch-up immunization schedule for persons ages 4 months through 18 years and the most recent updates online at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/.

Childhood immunization

General considerations

Definitions

Public health impact of immunization

Prevaccine Era: Peak Number of Cases (Year the Peak Occurred)

Vaccine Era: Number of Cases Reported in 2006

Percentage Decrease in Cases

Vaccine Introduced Before 1980

Diphtheria

30,508 (1938)

0

100

Smallpox

110,672 (1920)

0

100

Poliomyelitis (wild)

21,269 (1952)

0

100

Rubella

488,796 (1964)

11

99.99

Measles

763,094 (1958)

55

99.99

Mumps

212,932 (1964)

6584

96.91

Pertussis

265,269 (1934)

15,632

94.11

Tetanus

601 (1948)

41

93.18

Vaccine Introduced Between 1980 and 2005

Varicella (chickenpox)

5,358,595* (1988)

48,445

99.10

Hepatitis A

254,518* (1971)

3579

98.59

Acute hepatitis B

74,361* (1985)

4713

93.66

Invasive Haemophilus influenzae type B

20,000* (1984)

208

98.96

Invasive pneumococcal disease

64,400* (1999)

5169

91.97

Adverse effects of immunization

True Contraindications (Vaccine Should Not Be Administered)

Not Contraindications (Vaccine May Be Administered)

Anaphylactic reaction to a specific vaccine: Contraindicates further doses of that vaccine

Anaphylactic reaction to a vaccine component: Contraindicates use of all vaccines that contain that substance

Moderate or severe illnesses with or without a fever

Mild to moderate local reaction (soreness, erythema, swelling) following a dose of an injectable vaccine

Mild acute illness with or without low-grade fever

Diarrhea

Current antimicrobial therapy

Convalescent phase of illnesses

Prematurity (same dosage and indications as for normal, full-term infants)

Recent exposure to an infectious disease

Personal or family history of either penicillin allergy or nonspecific allergies

Vaccine information statements

Childhood immunization schedule

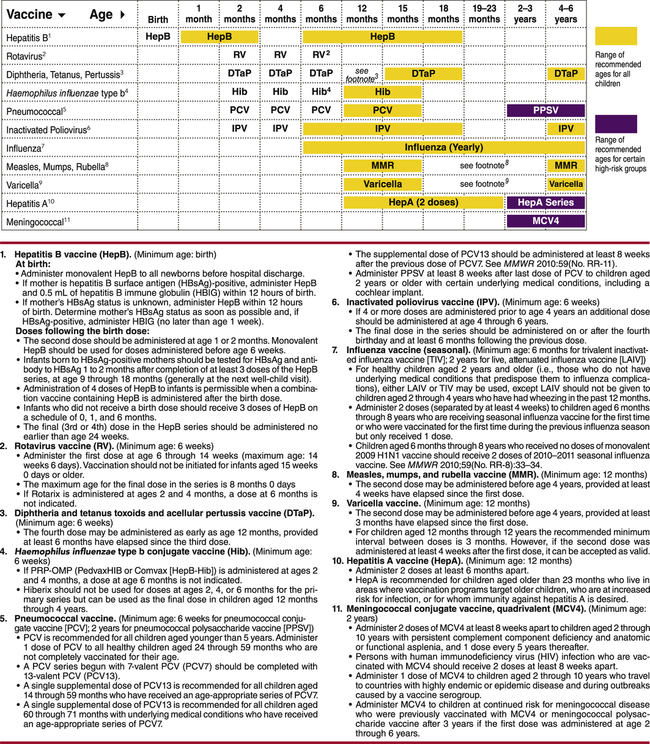

Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children from Birth Through 6 Years—United States, 2011.

Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children from Birth Through 6 Years—United States, 2011.

This schedule indicates the recommended ages for routine administration of currently licensed vaccines, as of December 21, 2010, for children from birth through age 6 years. These recommendations are approved by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). Gold-colored bars indicate recommended ages for each dose; a bar that spans more than one age bracket indicates an acceptable range of ages for that dose. Any dose not administered at the recommended age should be administered at any subsequent visit, when indicated and feasible. Licensed combination vaccines may be used whenever any components of the combination are both indicated and approved by the FDA for that dose of the series, provided other components of the combination are not contraindicated. Purple bars indicate certain high-risk groups.

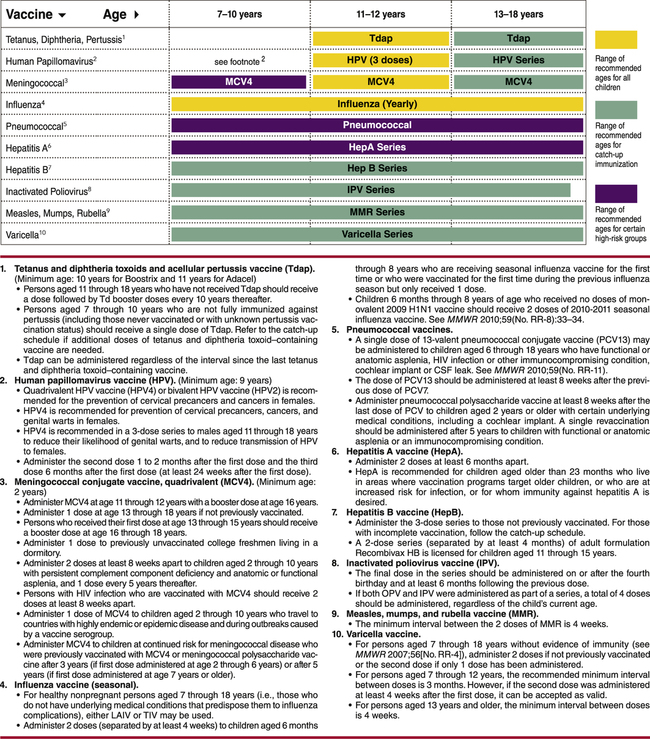

Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children 7 Through 18 Years of Age—United States, 2011.

Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children 7 Through 18 Years of Age—United States, 2011.

This schedule indicates the recommended ages for routine administration of currently licensed vaccines, as of December 21, 2010, for children from 7 through 18 years of age. These recommendations are approved by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). Gold-colored bars indicate recommended ages for each dose; a bar that spans more than one age bracket indicates an acceptable range of ages for that dose. Any dose not administered at the recommended age should be administered at any subsequent visit, when indicated and feasible. Licensed combination vaccines may be used whenever any components of the combination are both indicated and approved by the FDA for that dose of the series, provided other components of the combination are not contraindicated. Purple bars indicate certain high-risk groups. Green bars indicate times for catch-up immunization.

Target diseases

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Childhood immunization

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue