CHAPTER 11

Cerebrovascular Disease

Karen Fitzgerald

OBJECTIVES

1. List three risk factors associated with cerebrovascular disease.

2. Recognize two diagnostic tests to evaluate for cerebrovascular disease.

3. Review two treatments for medical management for the patient with cerebrovascular disease.

4. List three nursing diagnoses for the patient following carotid endarterectomy and patient management.

Introduction/Overview

Carotid artery disease is a major cause of ischemic stroke, the risk of which is directly related to the severity of stenosis and presence of symptoms. Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the United States, with approximately three quarters of a million strokes per year. Stroke is the leading cause of functional impairment, with more than 20% of survivors requiring institutional care and up to one third having a permanent disability (White et al., 2008).

The mortality rate following a stroke ranges from 26% to 52%. According to the most recent American Heart Association statistics, it is estimated that stroke accounts for half of all hospital admissions for acute neurologic disease. In addition, 28% of annual stroke victims are under the age of 65. Although strokes may be caused by a variety of disease entities, atherosclerosis is the most common contributing factor (A to Z Stroke Guide, 2011).

I. Anatomy

I. Anatomy

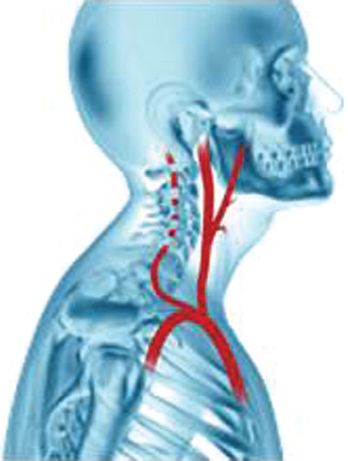

A. Carotid Artery (see Fig. 11-1)

1. Anterior blood supply to the brain is provided by the carotid arteries. The right common carotid artery originates from the innominate artery (brachiocephalic trunk), which is the first major branch of the aortic arch.

2. Left common carotid artery originates directly from the arch.

3. Common carotid arteries bifurcate into the internal and external carotid arteries.

4. External carotid arteries lie anterior to the internal carotid artery and gives off numerous branches, which supply the face.

FIGURE 11.1 Carotid, vertebral, and subclavian arteries.

5. Internal carotid artery has no major branch until the ophthalmic artery, which gives rise to the superficial and deep circulation of the eye (Bradley & Pearce, 1999).

B. Vertebral Arteries—Originate from the subclavian arteries bilaterally and provides the posterior circulation.

C. Basilar Artery—Major blood supply to the anterior spinal artery, brain stem, thalamus, cerebellum, and occipital lobe.

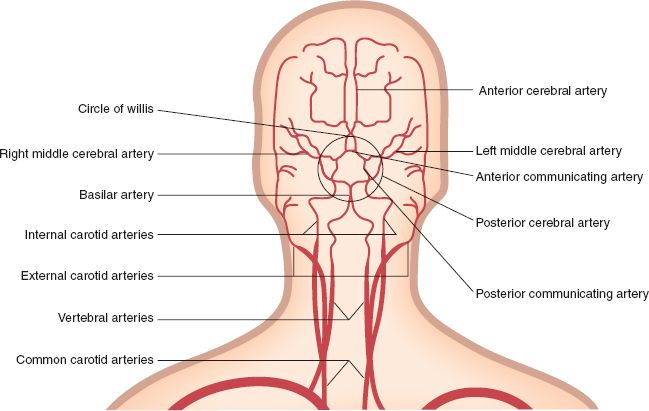

D. Circle of Willis—Consists of the four extracranial vessels (two vertebral and two carotid arteries), which join at the base of the skull (Bradley & Pearce, 1999) (see Fig. 11-2).

II. Pathophysiology

II. Pathophysiology

A. Atherosclerosis

1. Most common cause of cerebrovascular disease in the United States for individuals 65 years and older (Sullivan & Hertzer, 1996)

2. A diffuse disease characterized by the development of fatty streaks, plaque formation and plaque necrosis, and calcification (Graham & Ford, 1999)

3. Over time, the artery walls thicken, harden, and lose their elasticity, causing a decrease blood flow through the artery and eventually an obstruction of flow (Graham & Ford, 1999)

FIGURE 11.2 Carotid and cerebral circulation.

4. The lesions of atherosclerosis accumulate in large- and medium-sized arteries and seem best described by an inflammatory process that comprises a series of highly specific cellular and molecular reactions that lead to the accumulation of atherosclerotic plaque (Oppat & Graham, 2004)

5. Possible causes of inflammation are free radicals formed as by-products of smoking and diabetes, genetic malfunction of healing as might be seen in hyperhomocysteinemia, or infectious agents such as Chlamydia or other yet to be discovered organisms (Oppat & Graham, 2004)

6. The persistent inflammation within the vessel wall results in the accumulation of macrophages and lymphocytes in the vessel wall at the site of a fatty streak (Oppat & Graham, 2004)

B. Asymptomatic Disease

1. A patient with an asymptomatic 50% carotid stenosis has 1% to 2% per year risk of a stroke (Wiebers, Feigin, & Brown, 1997).

2. The risk of stroke is greatest for persons with neurologic symptoms such as transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), but is also increased in patients with asymptomatic lesions. The prevalence of hemodynamically significant carotid stenosis varies with age and other risk factors: population-based studies estimate that 0.5% of persons in their 50s and about 10% of those over 80 years have carotid stenosis greater than 50% (Wiebers et al., 1997).

3. Persons with asymptomatic stenoses are not only at increased risk for cerebrovascular accident, but also early detection can reduce morbidity due to cerebrovascular disease (Wiebers et al., 1997).

C. TIA

1. A TIA is a transient neurological deficit that lasts usually a few minutes. It occurs when the blood supply to part of the brain is briefly interrupted. TIA symptoms, which usually occur suddenly, are similar to those of stroke (Bradley & Pearce, 1999).

2. Symptoms of a TIA disappear within an hour, although they may persist for up to 24 hours (Bradley & Pearce, 1999).

3. Symptoms can include numbness or weakness in the face, arm, or leg, especially on one side of the body; confusion or difficulty in talking or understanding speech; trouble seeing in one or both eyes; and difficulty with walking, dizziness, or loss of balance and coordination (Bradley & Pearce, 1999).

D. Fibromuscular Dysplasia

1. Occurs primarily in White females and involves the larger arteries (renal, iliac, internal carotid arteries).

2. Usually bilateral, characterized by smooth muscle hyperplasia.

3. Internal carotid artery is most often affected, followed by the vertebral arteries (Graham & Ford, 1999).

E. Cervical Irradiation —External irradiation for malignant cervical lesions may damage the entire vessel wall and may accelerate atherosclerosis (Francfort, Smullens, Gallagher, & Fairman, 1989).

F. Carotid Dissection —Blunt trauma, sudden extension of the neck, or even paroxysms of coughing or vomiting may cause intimal tearing with subsequent carotid artery dissection (Spittell & Spittell, 1991).

G. Arteritis —Vasculitis of the giant cell type, often involving the aortic arch and its branches (e.g., Takayasu arteritis) (Bradely & Pearce, 1999).

III. Etiology/Precipitating Factors—Causes of arterial disease are varied. Atherosclerosis is the most common arteriopathy in the United States. A variety of nonatherosclerotic arterial diseases exist. These are less common and often less well defined than is atherosclerotic disease.

III. Etiology/Precipitating Factors—Causes of arterial disease are varied. Atherosclerosis is the most common arteriopathy in the United States. A variety of nonatherosclerotic arterial diseases exist. These are less common and often less well defined than is atherosclerotic disease.

IV. Assessment

IV. Assessment

A. Risk Factors and Primary Prevention

1. A variety of risk factors have been found to influence the atherosclerotic process: age, sex, hereditary, smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, sedentary lifestyle, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and stress (Gotto, 1986)

2. Risk Factor Modification

a. Smoking cessation

b. Control of hypertension

c. Lipid management

d. Diabetes management

e. Healthy diet

f. Regular exercise

B. Patient History—Symptoms vary according to the vessels involved. Timing is also important in the evaluation and classification of symptoms.

1. Subjective findings

a. TIAs: transient neurologic deficits, which resolve within 24 hours

1) Slurred or garbled speech or difficulty understanding others

2) Amaurosis fugax—Ocular TIA: sudden blindness in part of visual field, sometimes as if a gray or black curtain is falling over or crossing visual field

3) Dizziness, loss of balance, or loss of coordination

4) Sudden weakness, an abnormal feeling, or paralysis in face, arm or leg, typically on one side of the body

b. Completed stroke: deficits that persist and are permanent

2. Objective findings

a. Internal Carotid Artery Stenosis

1) Deficit whether temporary or permanent affecting one side of the body (hemiparesis, monoparesis, aphasia, dysarthria, monocular blindness). Lesions affect the ipsilateral side of the body.

2) Ultrasound and/or radiological findings (see V, Pertinent Diagnostic Testing).

b. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI)

1) Atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the vertebral arteries is less common than in carotid system.

2) Symptoms include dysarthria, global aphasia, diplopia, vertigo, syncope, dizziness, confusion, drop attacks (Bradley & Pearce, 1999).

C. Physical Examination

1. Inspection

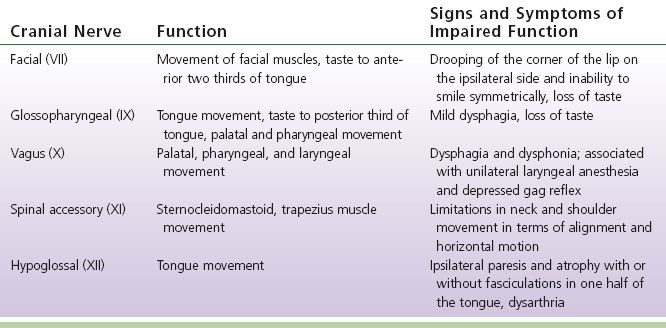

a. Neurological examination: check Cranial nerves (see Table 11-1)

b. Ophthalmoscopic examination if patient complains of amaurosis fugax to evaluate for retinal emboli (Young, 1996)

TABLE 11-1 Cranial Nerves, Functions, and Impairments

2. Palpation

a. The carotid pulse is palpated in the middle or lower neck between the trachea and the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

b. Palpate each carotid artery separately.

c. Check base of the neck and the supraclavicular fossa for pulsatile mass indicating an aneurysm or carotid body tumor (Young, 1996).

3. Auscultation

a. Listen with bell of stethoscope for bruit.

b. Carotid bruits are usually loudest in the upper third of the neck in the area of the carotid bifurcation.

c. A bruit is an audible sound associated with turbulent blood flow created by a change in the diameter of the arterial lumen (Bradley & Pearce, 1999).

d. Have the patient hold their breath, auscultate the carotid artery from the base of the neck to the angle of the jaw.

e. If the sound intensifies, it probably originates in the heart or the subclavian artery; a diminished sound usually signifies the bruit originates in the carotid artery (Young, 1996).

D. Considerations Across the Lifespan

1. Young adulthood

a. Consideration of risk factors, that is, smoking, cholesterol, hypertension, sedentary lifestyle, diet

b. If risk factors are not controlled there is an increase stroke risk

c. Fibromuscular dysplasia: most common in young women

2. Elderly

a. Consideration of risk factors

b. Age increases one’s risk for atherosclerosis therefore increasing one’s risk for carotid artery disease

c. Screening high-risk patients

V. Pertinent Diagnostic Testing

V. Pertinent Diagnostic Testing

A. Laboratory Testing

1. Complete blood count (CBC) and clotting profile if patient had TIA or stroke to assess for hypercoagulablity

2. Platelet activation is a key step in the development of cerebral ischemia due to atherosclerosis

B. Noninvasive Testing

1. Carotid duplex: uses high-frequency sound waves into the artery which are reflected by moving red blood cells. Identifies blood flow in the arteries

a. Detects flow disturbances within the vessel (Blackburn & Kennedy, 1999)

b. High accuracy of the duplex scan; many surgeons are performing surgery based solely upon the duplex scan itself

c. Is generally the initial test for evaluating carotid stenosis

d. Used for routine follow-up of the patient to detect recurrent stenosis after carotid endarterectomy (CEA) (Bradley & Pearce, 1999)

2. Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA)

a. Provide anatomic images of blood vessels that can be projected in a format similar to that of conventional angiography and also provide physiologic information

b. Is increasingly substituted for arteriography because it produces good depiction of blood vessels

c. The initial test for evaluating the carotids is ultrasound which is a good screening test

d. Many surgeons will now operate after ultrasound and/or MRA and forego arteriography

3. Computed Tomography (CT) Angiogram

a. Imaging study utilizing noncontrast and IV contrast to identify specific anatomy of the aortic arch, carotid arteries, and intracerebral arteries

b. May also be performed to identify those patients whose symptoms are due to tumors, hemangiomas, intracranial vascular disease, or subdural hematomas

c. Also used to detect stroke and is used postoperatively for any neurologic complication (Bradley & Pearce, 1999)

4. Arteriography: invasive testing

a. Contrast angiography is an effective method to demonstrate cerebrovascular stenosis (Jensen & Creager, 2003)

b. Remains the gold standard for diagnosis of carotid and other cerebrovascular stenoses and occlusions (Jensen & Creager, 2003)

c. In many centers, duplex ultrasonography, often combined with MRA, has replaced the need for most contrast angiograms (Jensen & Creager, 2003)

VI. Medical Management of Carotid Disease

VI. Medical Management of Carotid Disease

A. Risk Factor Modification

1. Elimination of risk factors such as, smoking, diet, exercise, cholesterol, blood pressure, and diabetes management have a significant impact on the alleviation of symptoms

2. The patient’s provider more than likely will recommend one of the following medical treatments prior to intervention such as angioplasty, stent, and/or surgery

3. Serial ultrasounds for progression of disease

B. Antiplatelet Therapy—Platelet activation is a key step in the development of cerebral ischemia due to atherosclerosis, and antiplatelet agents have proven useful therapeutic agents.

1. Aspirin

a. Indications: prophylaxis for recurrent TIA and stroke due to atherosclerosis

b. Aspirin in doses of 81 to 325 mg daily, alone or in combination with other agents have shown to have clinical efficacy in large multicenter trials

c. The mechanism of action of aspirin is to reduce platelet aggregation by inhibiting platelet cyclo-oxygenase and preventing the formation of Thromboxane A2 (Jensen & Creager, 2003)

2. Clopidogrel (Plavix)

a. Indications: reduction of atherosclerotic events (MI, stroke, and vascular death) in patients with atherosclerosis documented by a recent stroke or MI, or established peripheral artery disease

b. Is a selective and irreversible inhibitor of ADP-induced platelet aggregation

c. Normal dose: 75 mg daily (Nunnelee & Fotis, 2004)

3. Ticlopidine (Ticlid) (Discontinued brand in the United States)

a. Indications: is a thienopyridine, chemically similar to clopidogrel. Not considered as a first-line antiplatelet for stroke prevention because of the side effects and cost. The most severe side effect is neutropenia

b. Normal dose: 250 mg twice daily (Ticlid® product information, 2013)

4. Prasugrel (Effient)

a. Indications: a thienopyridine, also chemically similar to clopidogrel that inhibits adenosine diphosphate binding to platelet receptors (a platelet aggregation inhibitor). Thrombocytopenia and bleeding are the most severe side effects; in fact, the bleeding risk is higher than with clopidogrel

b. Use in caution in patients of 75 years or older secondary to uncertain risk of intracranial bleed and atrial fibrillation

c. Normal dose: loading dose of 60 mg, then 10 mg daily (Effient® product information, 2013)

C. Anticoagulation

1. Warfarin

a. Indications: thromboembolic disorders and events (deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, arterial thrombosis, embolism, arterial or venous graft failures, prosthetic valve, atrial fibrillation, coagulation disorders, cerebrovascular or extracranial carotid artery disease in patients of poor surgical risks; controversial)

b. Drug of choice in the United States for oral anticoagulation

c. Normal dose: individualized according to the International Normalized Ratio (INR) (Nunnelee & Fotis, 2004)

D. Interventional Therapies

1. Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty (PTA)

a. Less invasive then surgery

b. Since 1994, carotid angioplasty with stenting (CAS) has been investigated as an alternative treatment to CEA at multiple centers (Vitek, Roubin, Gishel, Al-Mubarek, & Iyer, 2000)

c. Generally reserved for nonatherosclerotic lesions such as fibromuscular dysplasia and for patients who have had radiation to the cervical region

2. Carotid artery stenting

a. Many types of vascular stents with different characteristics, in different stages of clinical use and FDA approval

b. Patency rate with stenting has been slightly higher compared with angioplasty alone

c. Candidates include patients with restenosis, previous neck surgery, or radiation on affected side

d. Patients are put on antiplatelet therapy pre- and postprocedure (Vitek et al., 2000)

VII. Surgical Management

VII. Surgical Management

A. CEA—Currently the most frequently performed vascular surgical procedure in the United States. The goal of this surgery is stroke prevention.

1. Overall morbidity and mortality rate is 3% nationally

2. Considered safe for patients with lesions >70%

B. Surgical Procedure

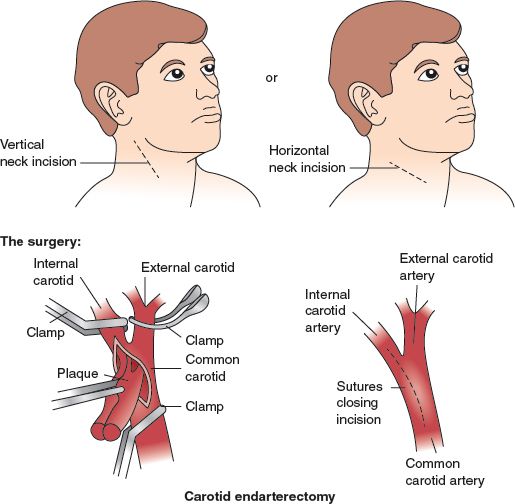

1. CEA (see Fig. 11-3)

a. Carotid bifurcation is exposed via a vertical incision made parallel to the sternocleidomastoid muscle under general or regional anesthesia (Bradley & Pearce, 1999).

b. Some surgeons use intraluminal shunting routinely, secondary to comfort level and type of anesthesia, whereas others use it selectively. Other methods of monitoring cerebral perfusion during clamping include electroencephalography (EEG) monitoring (Bradley & Pearce, 1999).

c. The common carotid artery, internal carotid artery, and the external carotid artery are clamped (Bradley & Pearce, 1999).

d. A longitudinal arteriotomy is made in the common carotid artery and extended to the internal carotid artery to the end of the plaque (Bradley & Pearce, 1999). Plaque is dissected out down to the media and then removed.

FIGURE 11.3 Carotid endarterectomy.