3 Care of the Child with Life-Limiting Conditions and the Child’s Family in the Pediatric Critical Care Unit

The PCCU is also a place for palliative care. How can the seemingly disparate approaches of high technology and high compassion work in concert for the benefit of children and families? The answer to this dilemma requires understanding the objectives of palliative care.32

Pearls

• Palliative care is a holistic approach to the care of the child and family when the child has a life-threatening or life-limiting condition.

• Palliative care is not the withdrawal of support, rather it is the active, total care of the child and family, with an emphasis on management of physical and emotional pain and suffering rather than on a cure for the child’s disease or condition.

• Healthcare providers need to be just as aggressive in providing palliative care as they are in providing curative therapies. Providers should begin plans to provide palliative care as soon as the life-threatening or life-limiting condition is diagnosed.

• There is never “nothing more we can do.” We can always support families as they navigate the difficult challenges of life-threatening or life-limiting conditions.

Definition

The most frightening news parents can receive is that their child has a life-threatening condition. Even more frightening and painful is the death of that child. These experiences often take place in a PCCU, where comprehensive palliative care is essential. Pediatric palliative care embraces a holistic approach to the care of a child with a life-threatening or life-limiting condition and the child’s family; it involves active, total care of the child’s body, mind, and spirit. Palliative care begins at the time of diagnosis and involves evaluating and alleviating a child’s physical, psychological, and social distress.57 To help support the best quality of life for these children, nurses need to have a clear understanding of the patients and families served, and must comprehensively address the needs of children with life-threatening conditions and their families. Nurses must provide care that responds to the anguish and suffering of patients and families, supports caregivers and healthcare providers, and cultivates educational programs.33

In the past, palliative care was not initiated until cure was no longer thought to be possible. However, many of the goals of cure-oriented and palliative care are the same, including interdisciplinary collaboration, clear and timely communication with families, and careful management of physical and emotional pain and suffering. Experts now believe that palliative care should begin whenever a potentially life-limiting condition is diagnosed.57 Unfortunately, children and families are often deprived of the benefits of palliative care because healthcare providers are reluctant to even discuss aggressive provision of comfort measures until all attempts to cure have been exhausted.

Pediatric palliative care focuses on the maintenance of quality of life for children and families, including a physical dimension that involves management of pain and distressing symptoms.26 Nurses who provide care to these children face many challenges. Physical care is important, but nurses must also address the emotional and psychological needs. A holistic family-centered model of care encourages family involvement in a mutually beneficial and supportive partnership.22 This chapter explores the needs of children with life-limiting conditions and their families in the PCCU setting, and it presents nursing interventions designed to meet the needs of the whole family.

Indications

Each year, approximately 54,000 children die in the United States, many after a lengthy illness.38 Most of these children die in hospitals, most often in neonatal and pediatric critical care units.11 The death of a child is an intensely painful experience, both emotionally and physically. In the United States, it is estimated that 1 million children are living with a serious, chronic illness that impacts their quality of life. In the PCCU, most diagnoses are potentially life-threatening or life-limiting and include trauma, cardiovascular conditions, respiratory compromise, congenital defects, and neurodegenerative disorders. Palliative care services can be beneficial at many times in the illness trajectory including diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, or end-of-life.

Historically, palliative care has been provided at the end-of-life in homes or hospice residences, but a need to integrate palliative care principles from the time of diagnosis throughout critical care interventions is becoming increasingly common. A growing number of patients with complex medical problems are alive as the result of PCCU technology, but now are dependent on that technology to continue living. These children often have residual cardiorespiratory or neurologic problems and require technologic support that is unavailable in or impractical for the home care setting. For some of these children, survival outside the hospital might not be the best option.10 Therefore, many of these children ultimately die in the PCCU. The PCCU staff might find it difficult to switch from life-saving interventions to care that focuses predominantly on addressing the comfort and psychological needs common to dying children and their families. Some children’s hospitals are developing pediatric palliative care teams or centers to ensure seamless continuity of care from critical care units to the home, and to assist the team in providing the best possible care for children with life-limiting conditions and their families.

Approaches to a family-centered model of care

Nothing can realistically prepare parents or children to face a child’s life-threatening illness or injury, but experienced nurses can provide invaluable guidance and support. Palliative care services are appropriately applied to both curable and incurable conditions, and children’s lives may be enhanced when many of the services are applied early in the course of disease treatment. Most, if not all, children with life-threatening conditions fear death or reoccurrence and pain and suffering. Caring for these children presents unique challenges for parents and for healthcare providers. Key ethical concepts include distinctions between withholding and withdrawing treatment and possible consequences such as double effect. The doctrine of double effect is used to describe giving medications with the intention of making a child comfortable, knowing one possible consequence is hastening the child’s death.51 Inherent in illness is the potential for pain and suffering that may be eased through appropriate family-centered palliative care. Strategies that enable children and their families to express their feelings, to identify realistic hopes and expectations, and to focus on using their strengths to their best advantage can facilitate optimal coping and adaptation. Family-centered care that incorporates the child’s social structure and relationships is regarded as a comprehensive ideal for end-of-life care. 51

The Child’s Needs

Admission and Diagnosis

Nurses can help families by providing careful explanations of events necessitating PCCU admission, the equipment present, and the care provided by the nursing staff. If the child is responsive, the child can be taught to communicate with the nursing staff. The child might be told, for example, that, because he has been very sick, he developed a problem in breathing, and that a soft tube (or airway or breathing tube) was put into his lungs (or into the windpipe) to help him breathe. The nurse might add that the staff is doing everything they can to help the child feel better, and the child’s parents and nurses will be close to his bed to care for him. Such communication is important even if the child appears to be unconscious. Call bells, alphabet and phrase boards, pointing, writing, and drawing can all help facilitate communication with the conscious intubated child.39,55

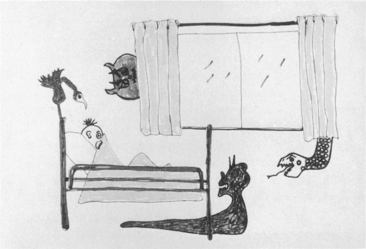

If intubation is not necessary, verbal communication is possible. The child’s questions can be more spontaneous, and the child’s answers can be more detailed and less influenced by the answer options provided by the parents or staff (i.e., not limited to yes or no). Conversations related to the PCCU environment may be stifled while the child remains in the PCCU. The child should be given many opportunities to express concerns, fears, questions, and preferences regarding care and termination of care (see Chapter 24; also see Special Considerations: Care of the Dying Adolescent in the Chapter 24 Supplement on the Evolve Website). Art and play therapy can provide a means of communication about the child’s fears, and discussion of the child’s art provides an opportunity to explore the child’s feelings (Fig. 3-1). Child life specialists can be particularly helpful in advocating for children’s wishes and assisting patients with self-expression (see also Table 2-1).

Physical Needs

Often the single most important aspect of physical care for the child with a life-limiting condition is the reduction or elimination of pain; however, studies have shown that many children are not adequately medicated to relieve their pain.16,32,56 While physicians and nurse practitioners will prescribe analgesics, nurses have a major role in recognizing and relieving pain. To identify and quantify pain and to evaluate the effectiveness of analgesics, the nurse should assess both physiologic and behavioral manifestations of pain (see Chapter 5 for further information).26,40,44 Although it can be extremely difficult to determine whether a preverbal, intubated, or obtunded child is in pain, the nurse can identify signs of distress through close observation of the child’s heart rate, respiratory rate, breathing effort, pupil size, muscle tone, and facial expression. The presence of a facial grimace or guarding, tension or flexion of muscles, pupil dilation, tachycardia, tachypnea, and diaphoresis all can indicate the presence of pain. If the nurse is unsure whether symptoms of pain are present, the nurse should ask the parents to assist in the determination of the child’s level of comfort.

Pain control uses both pharmacologic and psychologic measures (see Chapter 5 for further information about assessment and relief of pain). Although administration of analgesics can result in double effect, pain relief should be the most important physical consideration when death is inevitable.23 When healthcare team members are able to acknowledge that the child may be dying, the dying child is more likely to receive adequate analgesics

Specific treatment for dyspnea and respiratory distress in the PCCU are highly variable and need to be individualized, based on the underlying source of the dyspnea and the child’s level of consciousness and needs (see Principles of Withdrawing Life-Sustaining Treatments in the Chapter 24 Supplement on the Evolve Website). Supplementary oxygen, corticosteroids, diuretics, and bronchodilators may be useful approaches to care. Another relatively common symptom seen in dying children in the PCCU is delirium, which can be calm or agitated. Delirium decreases a child’s ability to receive, process, and recall information and can be mitigated with the reduction of noise and lights and by the presence of family members or familiar staff.51

Comfort measures are often as important as life-saving measures to a child with a life-limiting condition and to the child’s family. These measures can include but are not limited to soothing baths and backrubs, opportunities to be held and to play with favorite toys and pets, and diversional activities such as computers, movies, and favorite music. Such activities can reduce anxiety and pain and relieve the impersonal atmosphere of the PCCU environment.23

Emotional Needs

Establishment of effective communication is often challenging for family members, even when all are in good health. It can be especially challenging to establish effective communication for the child with a life-threatening condition, the child’s family members, and the child’s healthcare providers, because the child’s condition, treatment, and prognosis introduce additional stresses and fears (see Fig. 3-1). There are several critical points during the continuum of care when communication is especially important: at diagnosis, during exacerbations, and at the end of life. Frequently these critical points occur in a PCCU. Initiation of palliative care services might be delayed because it is difficult for families and healthcare providers to accept the fact that further curative treatment will be futile.

Parents will likely find it especially difficult to talk with the child about the severity of the child’s condition and poor or fatal prognosis. In a recent survey of parents after the death of a child with cancer, none of the parents who discussed death with their children regretted the discussions, while many of those who did not have such conversations wished they had.31 Parents were most likely to regret their failure to discuss death if they sensed that their child was aware that death was imminent.31 The nurse is often the best person to help the parents begin such discussions at appropriate times, and the nurse can help the parents to answer the child’s questions, reduce the child’s fears, and address the child’s concerns.

Spiritual Needs

Spiritual needs such as love, faith, hope, and beauty motivate human experiences, emotions, and relationships, and suffering can occur when these needs are not met.5 Palliative care attempts to address spiritual needs, bringing the child and family together around personal and private attempts to cope with questions about life and meaning that frequently result from feelings of powerlessness and helplessness.

It is important for healthcare providers to listen to families without using religious platitudes. Nurses and other members of the healthcare team can provide psychosocial and spiritual guidance consistent with family values, ideals, and choices.41 Nurses can provide a safe place where spiritual needs, uncertainty, and hope can be expressed. If hope for cure is no longer realistic, nurses can assist families in realizing other wishes, such as hoping the child does not experience pain or that the child is not alone when death comes.22 As a need for palliative care becomes apparent, parents may have intense spiritual needs. Nurses can support families through caring presence, words, and actions to foster trust.35

The Family’s Needs

Family Challenges and Strengths

Parents of chronically ill children, on the other hand, have experienced the child’s long, intense, and often complicated illness. They have likely experienced many crises during the course of the child’s illness and may have prepared repeatedly for the child’s death. Such a continuous roller-coaster of emotional stress can compromise the family’s ability to cope effectively with the child’s ultimate deterioration and death. When a child has a chronic illness and has recovered from many near-death experiences, families and healthcare professionals may be reluctant to abandon curative efforts and allow natural death. Such reluctance can result in missed opportunities for resolution and spiritual healing.27 Other family members and friends can provide valuable support, although occasionally such support people may refuse to believe that the child is really dying.

Emotional Needs

Parents may respond to a life-limiting condition or predicted death of the child with anticipatory grief. Anticipatory grief is a coping mechanism that is sometimes used when the death of a loved one is perceived as inevitable; the grieving process may begin before the death occurs, in anticipation of that loss. Parents may begin to grieve over their child’s condition at the time of diagnosis or at any time the child experiences a serious setback or relapse. Anticipatory grief has been shown to facilitate the grieving process because it provides time to prepare for loss, the opportunity to complete unfinished business and resolve conflicts, and time to say good-bye.8

Parents use a variety of strategies in response to the stress of a child’s illness. Coping involves conscious efforts to regulate emotion, behavior, and the environment through one’s response to a stressful event. Coping has been described in work with adolescents as either voluntary engagement coping or voluntary disengagement coping.14 Voluntary engagement coping includes primary control coping with direct attempts to influence stressors (e.g., problem solving, emotional expression, emotional regulation) and secondary control coping with attempts to adapt to the stressor (e.g., acceptance, cognitive restructuring, positive thinking, distraction). Parents and siblings can use either type of coping in dealing with a stressful situation, but when a situation is out of their control, evidence shows that secondary control coping seems to work best.15

Special situations affecting timing of death

Withholding or Withdrawing Treatment

Nurses often play an important role in helping parents make decisions about withholding treatments or attempted resuscitation or withdrawing therapy. The nursing staff members continuously observe the extent of the child’s suffering and its effects on the child and family, so nurses are often the best people to speak on behalf of the child and family. However, nurses must be able to objectively represent the concerns of the family during discussions with the healthcare team and must encourage parents to express preferences regarding treatment. The nurse must avoid adoption of a crusading approach during these discussions. If the nurse assumes a spokesperson role, that nurse is obligated to speak only for the child and family; the nurse’s personal opinions must be clearly distinguished from the expressed preferences of the child and family. Families benefit from and value a healthcare team that provides clear information and that hears and respects the family’s decisions.40

Emotional, religious, philosophical, legal, and ethical considerations are involved in these complex decisions. If such decisions are avoided, the terminally ill or dying child might be subjected to futile resuscitation attempts or might be forced to endure painful treatment, intubation, or surgical procedures. Often these treatments carry the risk of the most feared aspects of death: pain, loneliness, separation from parents, and loss of control. Nurses can help the child and family plan elements of a child’s last hours or days by facilitating decisions about who should be present, the location, and the timing for withdrawal of life support (see Plan for Withdrawal in the section on Principles of Withdrawing Life-Sustaining Treatments in the Chapter 24 Supplement on the Evolve Website).

If staff members and parents are unable to reach a decision about treatment termination or limitation, outside consultants may be needed to help the family and healthcare team consider the treatment options available. Historically, the federal government,43 medical13 and nursing3 disciplines, bioethics groups, and the courts4,12 have all played a part in addressing controversial issues. In the 1980s, federal legislation recommended formation of infant care review committees; in many hospitals these groups evolved into multidisciplinary ethics committees. Consultation with these committees can provide extremely helpful insight into the options available for the child. However, most decisions regarding treatment termination must still be made in consultation with the parents and the child’s primary physician, in accordance with state laws (see Chapter 24 for further information).

Futility legislation authorizes a healthcare team to withdraw suggested treatment if further life support is deemed medically inappropriate by the ethics committee and the hospital gives the family 10 days’ notice and attempts to transfer a child to an alternative provider.50 Because this legislation was passed in Texas, it is not recognized everywhere. In addition, laws can vary by state. A court order may be requested by a child-protective agency before life support is terminated for a severely ill child who is under protective custody (see Chapter 24; also see Foregoing Life-Sustaining Treatment in Children with Inflicted Trauma in the Chapter 24 Supplement on the Evolve Website). Such requests are based on individual agency policy rather than state or federal law. A court order is not required to remove ventilatory support when a child has been pronounced brain dead. These patients have died, and treatment should be discontinued (unless organ donation is pursued).

Limitation (or prevention) of attempted resuscitation requires a written document signed by a physician. Because verbal orders regarding resuscitation can be subject to confusion or misinterpretation, they should not be accepted. In the absence of a written order to the contrary, resuscitation must be initiated in the event of an in-hospital patient respiratory or cardiac arrest. However, an unsuccessful resuscitation attempt can be discontinued at any time by the physician in charge of the resuscitative efforts. If the family agrees with withdrawal of support—and only after they have made the decision to withdraw support—they should be offered the option of organ donation after cardiac death (DCD).30

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Be sure to check out the supplementary content available at

Be sure to check out the supplementary content available at