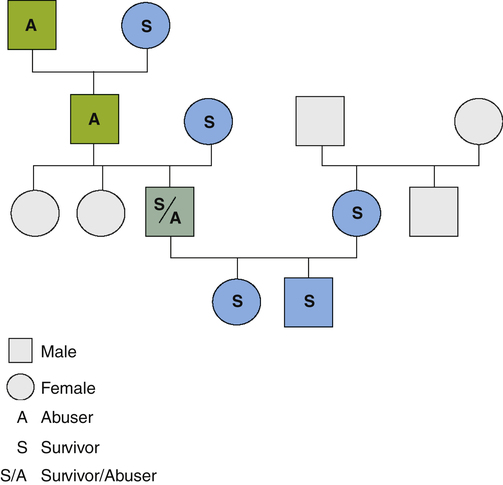

Nancy Fishwick, Barbara Parker and Jacquelyn C. Campbell When I was a laddie I lived with my granny And many a hiding my granny di’ed me. Now I am a man and I live with my granny And do to my granny what she did to me. 1. Define family violence, its possible causes, and characteristics of violent families. 2. Describe behaviors and values of nurses related to survivors of family violence. 3. Examine short-term and long-term effects of family violence on the physical and mental health of affected individuals. 4. Discuss primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention nursing actions related to family violence. 5. Analyze nursing assessment and intervention in abuse and violence among specific populations. 6. Evaluate issues and nursing care related to survivors of sexual assault. Multigenerational transmission means that family violence is often perpetuated through generations by a cycle of violence. Figure 38-1 shows the multigenerational transmission of family violence. Social learning theory related to violence suggests that a child learns this behavior pattern in a family setting by having an abusive parent as a role model. Experiencing abuse as a child does not necessarily determine an adult’s later behaviors. Many people who were abused as children are able to avoid violence within their intimate relationships and with their own children. The younger the child at the onset of abuse, the longer the duration and the more severe the nature of the abuse; multiple life adversities may set the stage for being abusive as a parent. A study with adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse found that many survivors felt they “passed on the family legacy” to their children, whereas other survivors made conscientious attempts to reject their family legacy and to create a new legacy for the well-being of their children (Martsolf and Draucker, 2008). Power issues appear to be a central factor in intimate partner abuse and violence. In marriage, abusers may justify the use of violence for trivial events, such as not having a meal ready or not keeping the children quiet. However, the controlling behaviors and violence often are related to one spouse’s need for total domination of the other spouse. For example, wife abuse often begins or escalates when the woman behaves more independently by working or attending school. Box 38-1 describes five forms of abuse within intimate relationships that reflect domestic struggles for power and control. Nursing care of survivors of violence can be challenging. The attitudes nurses bring to these situations shape their responses. Studies of health care professionals’ attitudes indicate that myths about family violence are accepted even though there is sympathy toward the survivor. Table 38-1 describes common myths and facts about survivors of abuse. TABLE 38-1 BEYOND THE MYTHS: RECOGNIZING ABUSE SURVIVORS Survivors often find the health care system to be unhelpful and even traumatizing when they go for help. Health care providers who use a paternalistic helping model rather than a model of empowerment will be frustrated by survivors who do follow the prescribed advice. Table 38-2 compares the characteristics of the paternalistic and the empowerment models. The empowerment model is more helpful to the survivor and is more professionally satisfying for the nurse. TABLE 38-2 COMPARISON OF THE PATERNALISTIC AND EMPOWERMENT MODELS OF INTERVENTION WITH BATTERED WOMEN The first step in providing effective nursing care is exploring your own attitudes toward survivors of abuse and violence. Self-directed learning and formal continuing education on family violence should focus on recognizing and changing beliefs and feelings, as well as learning facts about violence. Professional education materials from agencies such as Futures Without Violence (formerly the Family Violence Prevention Fund: http://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/section/our_work/health [accessed November 2011]) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention [accessed November 2011]); volunteer experiences with community-based rape crisis centers, domestic violence programs, or child protection programs; and attention to public education campaigns are constructive ways to increase understanding of and degree of comfort in addressing the experiences and responses of survivors. A growing body of knowledge provides nurses with an understanding of the short- and long-term effects of family abuse and violence on the physical, behavioral, and mental health of individuals (Sato-DiLorenzo and Sharps, 2007; Straus et al, 2009; McGuinness, 2010; Okuda et al, 2011). For example, a study of the cumulative effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) indicates a link between childhood adversity and the development of risky behaviors and chronic health problems in adulthood. The ACE study correlated adults’ childhood experiences of abuse, neglect, and various household problems such as witnessing domestic violence, having a family member with mental illness or substance abuse, or having a family member incarcerated, with later health behaviors such as early initiation of cigarette smoking, early initiation of sexual activity, or illicit drug use. It found that a significant number of adults with one or more adverse childhood events went on to develop alcoholism, depression, suicidality, unplanned pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart disease. The greater the number of types of adverse experiences in childhood, the higher the risk for adult health problems (Waite et al, 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). This work highlights the need for nurses to include assessment of adverse childhood experiences during intake of children, adolescents, and adults in mental health and substance abuse care settings. Survivors of family violence often experience a range of physical symptoms not obviously related to their injuries, such as headaches, menstrual problems, chronic pain, and digestive and sleeping disturbances. Symptoms such as headaches and other forms of chronic pain may be the result of repeated blows to the head or other parts of the body. The stress experienced from past or ongoing family violence may negatively affect the immune system, putting the individual at risk for a variety of health problems. Maternal exposure to domestic violence is associated with significantly increased risk for low birth weight and preterm birth (Shah and Shah, 2010). An emotionally abusive family environment, the experience of physical and sexual abuse, and witnessing maternal battering can have a negative impact on a person’s mental health immediately or as delayed reactions (Warshaw et al, 2009; Yanos et al, 2010). Nurses often are involved in the recovery process of adults who, years after the traumatic events, are dealing with the effects of childhood sexual abuse. Common psychological responses include the cognitive responses of self-blame and poor problem solving and the emotional responses of depression, anxiety, and lowered self-esteem (Al-Modallal et al, 2008). In children, trauma as a result of maltreatment can even result in psychotic symptoms (Arseneault at el, 2011). Many adults who witnessed family violence in their childhood, who personally experienced childhood abuse, or who survived abuse in adult intimate relationships can display remarkable adaptability in the wake of such trauma. Resilience, a pattern of successful coping despite challenging or threatening circumstances, can buffer a person from serious psychological effects. Access to social support and having a sense of control over the recovery process also contribute to favorable outcomes after abuse or assault (Paranjape and Kaslow, 2010). Depression and low self-esteem are common among women in abusive relationships, adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse, abused children, and survivors of other forms of violence. Problems with self-concept are described in Chapter 17, depression is discussed in Chapter 18, and resilience is explained in Chapter 12. All nurses have important roles to play in the prevention of family violence. They do this through educating the public, identifying risk factors, and detecting the actual occurrence of family violence to assure timely intervention and prevent future recurrence (Humphreys and Campbell, 2011). Secondary prevention efforts involve identification of families at risk for abuse, neglect, or exploitation, as well as early detection of those who are being abused or who are beginning to become violent. Systematic assessment for abuse through specific questions in the health history and through careful observations of physical health and behavior are recommended in all health care settings (Svavarsdottir and Orlygsdottir, 2008; O’Campo et al, 2011). Studies conducted in emergency departments, prenatal care settings, primary care settings, and in mental health care and substance abuse settings indicate that individuals are likely to disclose abuse when a concerned health care professional asks questions that invite disclosure. Several protocols are available for routine assessment for potential child abuse, abuse of intimate partners, and for abuse of elder adults. These resources are available for free download on the Futures without Violence website (http://www.futureswithoutviolence.org [accessed November 2011]). Box 38-2 lists indicators of actual or potential abuse that should be included in a nursing assessment. Availability and storage of firearms or other deadly weapons in the home need to be addressed because easy access has played a role in intentional injuries to family members and in communities and schools. Early indicators of families at risk include violence in the family of origin of either partner, communication problems, and excessive family stress, such as an unplanned pregnancy, unemployment, or inadequate family resources.

Care of Survivors of Abuse and Violence

Dimensions of Family Violence

Characteristics of Violent Families

Multigenerational Transmission

Use and Abuse of Power

Nursing Attitudes Toward Survivors of Violence

MYTH

FACT

Family violence is most common among families living in poverty.

Family violence occurs at all levels of society without regard to age, race, culture, status, education, or religion. It may be less evident among the affluent because they can afford private physicians, attorneys, counselors, and shelters. People with less money must turn to public agencies for help.

Violence rarely occurs between dating partners.

Estimates vary, but violence does occur in a large percentage of dating relationships.

Abused spouses can end the violence by divorcing their abuser.

About 75% of all spousal attacks occur between people who are separated or divorced. In many cases, the separation process brings on an increased level of harassment and violence.

The abused partner can learn to stop doing things that provoke the violence.

In a battering relationship, the abuser needs no provocation to become violent. Violence is the abuser’s pattern of behavior, and the abused partner cannot learn how to control it. Even so, many abused partners blame themselves for the abuse, feeling guilty—even responsible—for doing or saying something that seems to trigger the abuser’s behavior.

Alcohol, stress, and mental illness are major causes of physical and verbal abuse.

Abusive people and even those who are abused often use those conditions to excuse or minimize the abuse; but abuse is a learned behavior, not an uncontrollable reaction. People are abusive because they have acquired the belief that violence and aggression are acceptable and effective responses to real or imagined threats. Fortunately, because violence is a learned behavior, abusers can benefit from counseling and professional help to alter their behavior; but dealing only with the perceived problem (e.g., alcohol, stress, mental illness) will not change the abusive tendencies.

Violence occurs only between heterosexual partners.

Gay and lesbian partners experience violence for varied reasons, similar to heterosexual partners.

Being pregnant protects a woman from battering.

Battering often begins or escalates during pregnancy. According to one theory, the abuser who already has low self-esteem views his wife as his property. He resents the intrusion of the fetus and the extra attention his wife gets from friends, family, and health care providers.

Abused women accept the abuse by concealing it, not reporting it, or failing to seek help.

Many women, when they do try to disclose their situation, are met with denial or disbelief. This only discourages them from persevering.

PATERNALISTIC MODEL

EMPOWERMENT MODEL

Nurse is perceived to be more knowledgeable than the survivor.

Knowledge and information are shared mutually.

Responsibility for ending the violence is placed on the survivor.

The nurse strategizes with the survivor.

Survivors are helped to recognize societal influences.

Advice and sympathy are given rather than respect.

The survivor’s competence and experience are respected.

Creating Positive Attitudes

Health Effects of Family Abuse and Violence

Physical Health Effects

Psychological Effects

Preventive Nursing Interventions

Secondary Prevention

Care of Survivors of Abuse and Violence

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access