Chapter 69 Care of Patients with Urinary Problems

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

3. Encourage everyone to have a daily fluid intake of 1.5 to 2.5 L unless another health problem requires fluid restriction or to have sufficient fluid intake to result in urine output of 2 to 2.5 L daily.

4. Teach women risk-reduction interventions for urinary tract infections.

5. Teach the proper application of pelvic floor exercises to reduce or prevent urinary incontinence.

6. Encourage anyone who comes into contact with chemicals as part of work or hobbies to use appropriate personal protective equipment to reduce the risk for bladder cancer.

7. Use language the patient is comfortable with when discussing urinary and sexual issues.

8. Encourage patients and families to express their feelings and concerns about a change in urinary elimination.

9. Explain to the patient and family what to expect during tests and procedures for urinary problems.

10. Refer patients with long-term urinary problems to appropriate community resources and support groups.

11. Coordinate care to prevent urinary tract infections among hospitalized patients.

12. Compare the pathophysiology and manifestations of stress incontinence, urge incontinence, overflow incontinence, mixed incontinence, and functional incontinence.

13. Coordinate nursing care for the patient who has invasive bladder cancer.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Renal Stone; Kidney Stone; Nephrolithiasis

Animation: Insertion of Foley Catheter

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Urinary problems affect the storage or elimination of urine. Both acute and chronic urinary problems are common and costly. More than 20 million people in the United States are treated annually for urinary tract infections, cystitis, kidney and ureter stones, or urinary incontinence (U.S. Renal Data Systems, 2010). Although life-threatening complications are rare with urinary problems, patients may have significant functional, physical, and psychosocial changes that reduce quality of life. Nursing interventions are directed toward prevention, detection, and management of urologic disorders.

Infectious Disorders

Infections of the urinary tract and kidneys are common, especially among women. Manifestations of urinary tract infection (UTI) account for more than 7 million health care visits and 1 million hospital admissions annually in the United States (U.S. Renal Data Systems, 2010). UTIs are the most common health care–acquired infection. Total direct and indirect costs for adult urinary tract infections are estimated at $1.6 billion each year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009).

Urinary tract infections are described by their location in the tract. Acute infections in the urinary tract include urethritis (urethra), cystitis (bladder), and prostatitis (prostate gland). Acute pyelonephritis is a kidney infection. The site of infection is important to know because site, along with the specific type of bacteria present, determines treatment. Several risk factors are associated with occurrence of UTIs (Table 69-1).

TABLE 69-1 FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

Cystitis

Pathophysiology

Infectious agents, most commonly bacteria, move up the urinary tract from the external urethra to the bladder. Less common, spread of infection through the blood and lymph fluid can occur. Once bacteria enter the urinary tract, several factors influence the outcome (Table 69-2).

TABLE 69-2 IMPORTANT FACTORS INFLUENCING THE OUTCOME OF URINARY TRACT INFECTION

| FACILITATING ASPECTS | PROTECTIVE ASPECTS |

|---|---|

| Anatomy | |

| Females: Short length of the urethra and its proximity to the vagina and rectum facilitate colonization of coliform bacteria. | |

| Males: With age, the prostate enlarges and may obstruct the normal flow of urine, producing stasis. | Males: Long length of the urethra and its distance from the rectum provide protection from colonization with coliform bacteria. |

| Physiology | |

| Females: Pregnancy predisposes a woman to ureteral reflux and subsequent pyelonephritis; with age, the decline in estrogen facilitates colonization of Escherichia coli. In addition, vaginal atrophy can alter urethral competency. Males: With age, prostatic secretions lose their antibacterial characteristics and predispose to bacterial proliferation in the urine. | Females: Well-estrogenized mucosa in the urethra and trigone may inhibit bacterial colonization and enhance urogenital blood flow. Males: Normal prostatic secretions inhibit bacterial growth. Both males and females: Mucin is produced by urothelial cells lining the bladder—this helps maintain mucosal integrity and prevent cellular damage; mucin may also prevent bacteria from adhering to urothelial cells. |

| Trauma | |

| Females: Vaginal penetration with sexual intercourse may traumatize the urethra and bladder base, leading to postcoital (or “honeymoon”) cystitis; a vaginal diaphragm that is too large can place pressure on the urethra, causing trauma; vaginal childbirth can cause permanent damage to the urethra. Males: Sexually transmitted diseases may cause urethral strictures that obstruct the flow of urine and predispose to urinary stasis. Both males and females: Urethral instrumentation (e.g., catheterization) may disturb the urothelial surface and predispose to adherence of bacteria that would ordinarily not be pathogenic. | Females: Adequate lubrication, either natural or artificial, with intercourse may prevent any trauma. |

| Infectious Agent | |

| Some organisms are better able to adhere to host cells and secrete substances that induce inflammation. | A small inoculum (number of microorganisms introduced into the body) is more easily flushed away by the flow of urine. |

Etiology and Genetic Risk

UTIs, like other infections, are the result of interactions between a pathogen and the host. Usually, a high bacterial virulence (ability to invade and infect) is needed to overcome normal strong host resistance. However, a compromised host is more likely to become infected even with bacteria that have low virulence. Genetically, invading bacteria with special adhesions are more likely to cause ascending UTIs that start in the urethra or bladder and move up into the ureter and kidney. Patient-specific genetic factors such as blood type and ability to produce bladder surface biofilms that protect bacteria may influence the risk for UTI (Bowen & Hellstrom, 2007).

Infectious cystitis is most commonly caused by organisms from the intestinal tract. About 90% of UTIs are caused by Escherichia coli. Less common organisms include Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and organisms from the Proteus and Enterobacter species (Bowen & Hellstrom, 2007).

How a catheter-related infection occurs varies between genders. Bacteria from a woman’s perineal area are more likely to ascend to the bladder by moving along the outside of the catheter. In men, bacteria tend to gain access to the bladder from inside the lumen of the catheter. Any break in the closed urinary drainage system allows bacteria to move through the urinary tract. Best practices to reduce the risk for catheter contamination and catheter-related UTIs are listed in Chart 69-1.

Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

Minimizing Catheter-Related Infection

• Assess patients daily for those who no longer need indwelling catheters.

• Consider appropriate alternatives to an indwelling catheter.

• Use aseptic routine when handling catheter devices; manipulation can promote an environment favorable to pathogens.

• Select a small-size catheter (14 to 18 Fr with a 5-mL balloon).

• Use strict sterile technique to insert the catheter (in the hospital setting); a break in technique can introduce pathogens into the urinary tract.

• Do not inject more than 10 mL into the balloon.

• Maintain a closed-system irrigation by ensuring that catheter tubing connections are sealed securely; disconnections can introduce pathogens into the urinary tract.

• Avoid routine catheter irrigation.

• Keep urine collection bags below the level of the bladder at all times; elevating the collection bag above the bladder causes reflux of pathogens from the bag into the urinary tract.

• Secure the catheter to the patient’s thigh (women) or lower abdomen (men); catheter movement can cause urethral friction and irritation.

• Perform daily catheter care by washing the perineum and proximal portion of the catheter with soap and water and drying gently (removes pathogens and reduces pathogenic population).

• Consider the use of coated catheters for patients requiring indwelling catheters for more than 3 to 5 days. This coating reduces bacterial colonization along the catheter.

Data from Smith, J. (2003). Indwelling catheter management: From habit to evidence-based practice. Ostomy and Wound Management, 49(12), 34-45.

Viral and parasitic infections are rare and usually are transferred to the urinary tract from an infection at another body site. For example, Trichomonas, a parasite found in the vagina, can also be found in the urine. Treatment of the vaginal infection (see Chapter 74) also resolves the UTI.

Interstitial cystitis is a rare, chronic inflammation of the bladder, urethra, and adjacent pelvic muscles that is not a result of infection. The condition affects women ten times more often than men, and the diagnosis is difficult to make. Manifestations are similar to those of infectious cystitis with voiding occurring as often as 60 times daily, more intense urgency preceding urination, and suprapubic or pelvic pain, sometimes radiating to the groin, vulva or rectum, that is relieved by voiding. Results from urinalysis and urine culture are negative for infection (Evans & Sant, 2007; Siegel et al., 2008).

The spread of the infection from the urinary tract to the bloodstream is termed urosepsis and is more common among older adults (Kessenich, 2010). Sepsis from any source is a systemic infection that can lead to overwhelming organ failure, shock, and death. The most common cause of sepsis in the hospitalized patient is a UTI (CDC, 2009). Sepsis has a high mortality and prolongs hospital stays (see Chapter 39).

Incidence/Prevalence

The incidence of UTI is second only to that of upper respiratory infections in primary care. Patients who have frequency (an urge to urinate frequently in small amounts), dysuria (pain or burning with urination), and urgency (the feeling that urination will occur immediately) account for more than 5 million health care visits annually. About 50% of these patients will have a confirmed UTI (U.S. Renal Data Systems, 2010).

Considerations for Older Adults

The prevalence of UTIs varies with age and gender. Women of any age are more commonly affected with UTIs than are men. In men, the incidence of UTI greatly increases after 73 years of age. In women, the prevalence of UTIs increases from 20% among all women to 50% in those older than 80 years (U.S. Renal Data Systems, 2010). Skin and mucous membrane changes from a lack of estrogen appear to account for much of the increased risk in older women. Prostate disease increases risk for UTIs in men.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Although cystitis is common, in many cases it is preventable. In the health care setting, reducing the use of indwelling urinary catheters is a major prevention strategy (Gray, 2010). When catheters must be used, strict attention to sterile technique during insertion can reduce the risk for UTIs as can consistent and adequate perineal and catheter care (see Chart 69-1).

Action Alert

Changes in fluid intake patterns, urinary elimination patterns, and hygiene patterns can help prevent or reduce cystitis in the general population. Teach all people to have a minimum fluid intake of 1.5 to 2.5 L daily unless fluid restriction is required for other health problems. Another strategy is to have sufficient fluid intake to cause 2 to 2.5 L of urine daily. Encourage people to drink more water rather than sugar-containing drinks. Teach people to avoid urinary stasis by urinating every 3 to 4 hours rather than waiting until the bladder is greatly distended. Encourage everyone either to shower daily or to wash the perineal and urethral areas daily with mild soap and a water rinse. Teach women to avoid the use of vaginal washes. Other hygiene measures that specifically reduce the risk for cystitis and other UTIs are listed in Chart 69-2.

Chart 69-2 Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Preventing a Urinary Tract Infection

• Drink at least 2 to 3 L of sugarless fluid every day.

• Be sure to get enough sleep, rest, and nutrition daily.

• [For women] Clean your perineum (the area between your legs) from front to back.

• [For women] Avoid using or wearing irritating substances, such as bubble bath, nylon underwear, and scented toilet tissue. Wear loose-fitting cotton underwear.

• [For women] Empty your bladder before and after intercourse.

• For both women and men, gently wash the perineal area before intercourse.

• Avoid the use of scented or flavored lubricants.

• If you experience burning when you urinate, if you have to urinate frequently, or if you find it difficult to begin urinating, notify your physician or other health care provider right away, especially if you have a chronic medical condition (e.g., diabetes) or are pregnant.

• Empty your bladder as soon as you feel the urge to urinate.

• Empty your bladder regularly (every 4 hours), even if you do not feel the urge to urinate.

• You may try these home therapies:

• To prevent recurrent infection:

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Frequency, urgency, and dysuria are the common manifestations of a urinary tract infection (UTI), but other manifestations may be present (Chart 69-3). Urine may be cloudy, foul smelling, or blood tinged. Ask the patient about risk factors for UTI during the assessment (see Table 69-1). For noninfectious cystitis, the Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency (PUF) Patient Symptom Scale can identify patients with interstitial cystitis.

Urinary Tract Infection

UTI, Urinary tract infection.

Laboratory Assessment

Laboratory assessment for a UTI is a urinalysis with testing for leukocyte esterase and nitrate. The combination of a positive leukocyte esterase and nitrate is 68% to 88% sensitive in the diagnosis of a UTI (Bowen & Hellstrom, 2007). Although a urinalysis can include a microscopic count of bacteria, white blood cells (WBCs), and red blood cells (RBCs), this additional testing is more expensive, is time consuming, and may not improve diagnostic accuracy. The presence of more than 20 epithelial cells/high power field (hpf) suggests contamination. The presence of 100,000 colonies/mL or the presence of three or more WBCs (pyuria) with RBCs (hematuria) indicates infection.

Occasionally the serum WBC count may be elevated, with the differential WBC count showing a “left shift” (see Chapter 19). This shift indicates that the number of immature WBCs is increasing in response to the infection. As a result, the number of bands, or immature WBCs, is elevated. Left shift most often occurs with urosepsis and rarely occurs with uncomplicated cystitis, which is a local rather than a systemic infection.

Other Diagnostic Assessment

The diagnosis of cystitis is based on the history, physical examination, and laboratory data. If urinary retention and obstruction of urine outflow are suspected, urography, abdominal sonography, or computed tomography (CT) may be needed to locate the site of obstruction or the presence of calculi. Voiding cystourethrography (see Chapter 68) is needed when ureteral reflux is suspected.

Cystoscopy (see Chapter 68) may be performed when the patient has recurrent UTIs (more than three or four a year). A urine culture is performed first to ensure that no infection is present. If infection is present, the urine is sterilized with antibiotic therapy before the procedure to reduce the risk for sepsis. Cystoscopy identifies abnormalities that increase the risk for cystitis. Such abnormalities include bladder calculi, bladder diverticula, urethral strictures, foreign bodies (e.g., sutures from previous surgery), and trabeculation (an abnormal thickening of the bladder wall caused by urinary retention and obstruction). Retrograde pyelography, along with the cystoscopic examination, shows outlines and images of the drainage tract. Areas of obstruction or malformation and the presence of reflux are then identified early.

Interventions

Nonsurgical Management

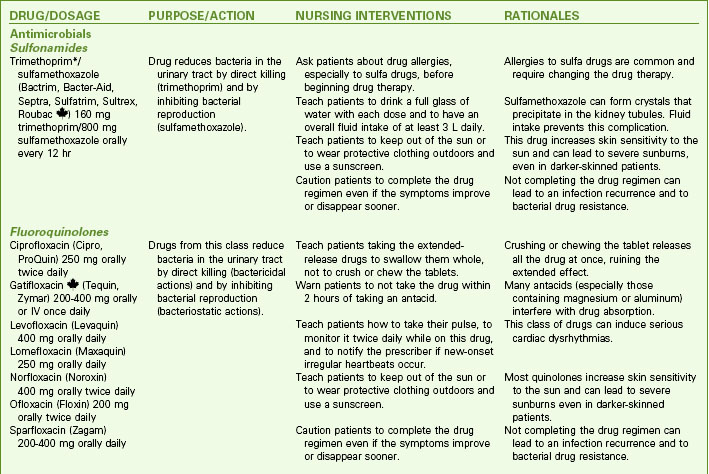

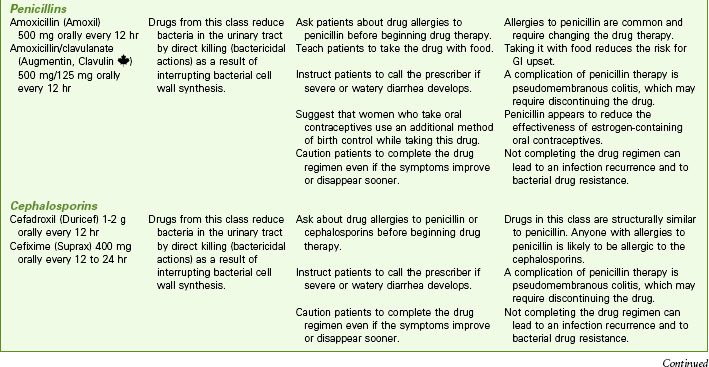

Drug Therapy

Drugs used to treat bacteriuria and promote patient comfort include urinary antiseptics or antibiotics, analgesics, and antispasmodics. Cure of a UTI depends on the antibiotic levels achieved in the urine (Chart 69-4). Oral antifungal agents are usually prescribed for fungal infections. When oral antifungal therapy is not sufficient, amphotericin B is most often given in daily bladder instillations. Antispasmodic drugs decrease bladder spasm and promote complete bladder emptying.

Antibiotic therapy is used for bacterial UTIs (see Chart 69-4). Guidelines indicate that a 3-day, high-dose course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole or a fluoroquinolone is effective in treating uncomplicated, community-acquired UTIs in women (Bowen & Hellstrom, 2007). Fluoroquinolones cannot be used to treat UTIs during pregnancy because of the potential for birth defects. The shorter courses increase adherence and reduce cost. Longer antibiotic treatment (7 to 21 days) and/or different agents are required for hospitalized patients; those with complicating factors, such as pregnancy, indwelling catheters, or stones; and those with diabetes or immunosuppression.

Drug Alert

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Nutrition Therapy

The diet should include all food groups and include more calories for the increased metabolism caused by infection. Urge patients to drink enough fluid to maintain a diluted urine throughout the day and night unless fluid restriction is required for other health problems. The drinking of 50 mL of concentrated cranberry juice daily appears to decrease the ability of bacteria to adhere to the epithelial cells lining the urinary tract, decreasing the incidence of symptomatic UTIs in some patients. Cranberry juice must be consumed for 3 to 4 weeks to be effective, and the efficacy of cranberry tablets has not been established (Bowen & Hellstrom, 2007). It is important to note that cranberry juice is an irritant to the bladder with interstitial cystitis and should be avoided by patients with this condition. Avoiding caffeine, carbonated beverages, and tomato products may decrease bladder irritation during cystitis.

Community-Based Care

Patients may associate symptoms of discomfort with sexual activities and have feelings of guilt and embarrassment. Open and sensitive discussions with a woman who has recurrences of UTI after sexual intercourse can help her find techniques to handle the problem (see Chart 69-2). Explore with her the factors that contribute to her infections, such as sexual penetration when the bladder is full, diaphragm use, and her general resistance to infection. Some positions during intercourse may reduce urethral irritation and subsequent cystitis. Remind the patient that although perineal washing before intercourse is helpful, vigorous cleaning of the perineum with harsh soaps and vaginal douching may irritate the perineal tissues and increase the risk for UTI. At the patient’s request, discuss the problem with her and her partner to help them find ways of maintaining their intimate relationship.

Patient-Centered Care; Evidence-Based Practice

1. Is this patient’s understanding of the cause of recurrent cystitis correct? Why or why not?

2. What other assessment data should you obtain and why?

3. What will you tell her about the effectiveness of her actions to reduce the need to urinate at a public toilet?

4. What techniques could you suggest for her to use a public toilet for urination?

Noninfectious Disorders

Urinary Incontinence

Pathophysiology

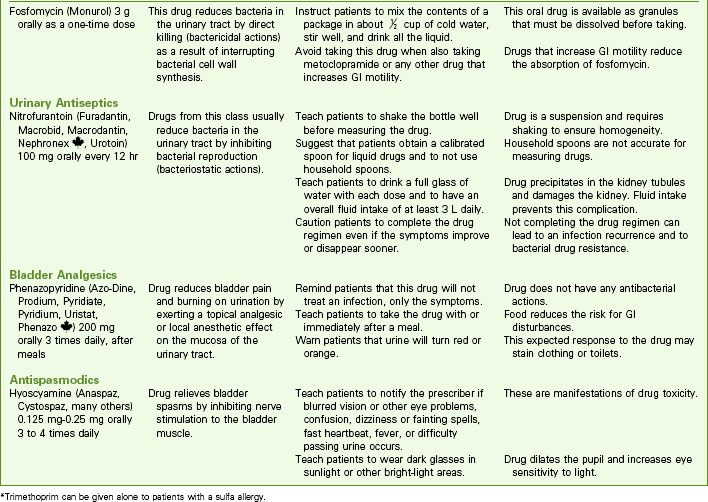

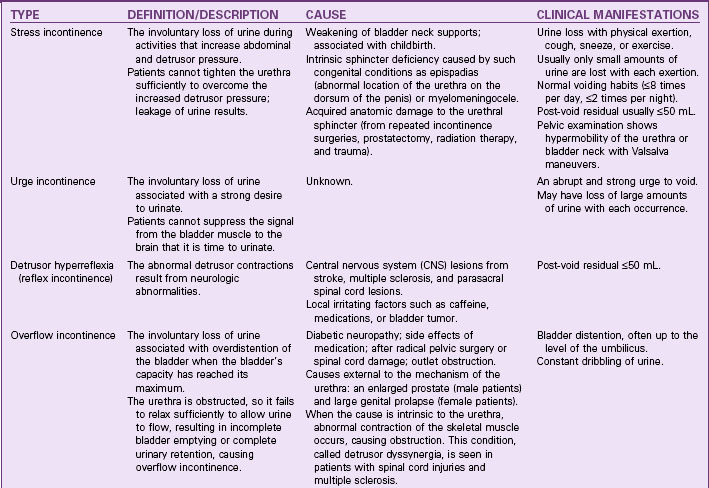

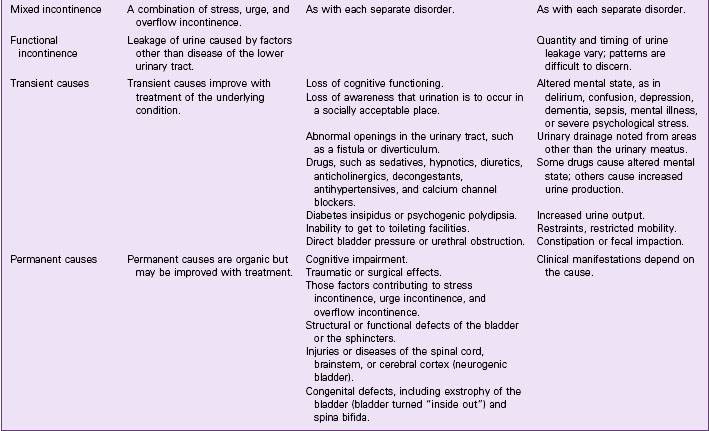

Continence occurs when pressure in the urethra is greater than pressure in the bladder. For normal voiding to occur, the urethra must relax and the bladder must contract with enough pressure and duration to empty completely. Voiding should occur in a smooth and coordinated manner under a person’s conscious control. Incontinence has several possible causes and can be either temporary or chronic (Table 69-3). Temporary causes usually do not involve a disorder of the urinary tract. The most common forms of adult urinary incontinence are stress incontinence, urge incontinence, overflow incontinence, functional incontinence, and a mixed form.

Etiology and Genetic Risk

Considerations for Older Adults

Many factors contribute to urinary incontinence in older adults (Chart 69-5). An older person may have decreased mobility from many causes. In inpatient settings, mobility is limited when the older patient is restrained or placed on bedrest. Vision and hearing impairments may also prevent the patient from locating a call light to notify the nurse or assistive personnel of the need to void. Assess for these factors, and minimize them to prevent urinary incontinence. Getting out of bed to urinate is a common cause of falls among older adults.

Chart 69-5 Nursing Focus on the Older Adult: Factors Contributing to Urinary Incontinence*

Drugs

• Central nervous system depressants, such as opioid analgesics, decrease the patient’s level of consciousness and the urge to void, and they contribute to constipation.

• Diuretics cause frequent voiding, often of large amounts of urine.

• Multiple drugs can contribute to changes in mental status or mobility, and they can irritate the bladder.

• Anticholinergic drugs or drugs with anticholinergic side effects are especially challenging, because they affect both cognition and the ability to void. Monitor patient responses to these drugs early in treatment.

Inadequate Resources

• Patients who need assistive devices (e.g., eyeglasses, cane, walker) may be afraid to ambulate without them or without personal assistance.

• Products that help patients manage incontinence are often costly.

• No one may be available to assist the patient to the bathroom or help with incontinence products.

Incidence/Prevalence

Incontinence is a major health problem that affects more than 13 million people of all ages in the United States (Agency for Health Care Policy and Research [AHCPR], 2001a); about 85% are women. It is most common in older adults, including 15% to 30% of community-dwelling older people and at least one half of all nursing home residents (AHCPR, 2001a).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree