Chapter 58 Care of Patients with Stomach Disorders

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Describe the importance of collaborating with members of the health care team when caring for patients with stomach disorders.

2. Identify community resources for patients with gastric disorders.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

3. Develop a teaching plan for patients about complementary and alternative therapies that have been used to help manage gastritis and peptic ulcer disease (PUD).

4. Plan interventions to promote GI health and prevent gastritis.

6. Compare etiologies and assessment findings of acute and chronic gastritis.

7. Identify risk factors for gastritis.

8. Compare and contrast assessment findings associated with gastric and duodenal ulcers.

9. Identify the most common medical complications that can result from PUD.

10. Describe the purpose and adverse effects of drug therapy for gastritis and PUD.

11. Monitor patients with PUD and gastric cancer for signs of upper GI bleeding.

12. Prioritize interventions for patients with upper GI bleeding.

13. Plan individualized care for the patient having gastric surgery.

14. Explain the purpose and procedure for gastric lavage.

15. Evaluate the impact of gastric disorders on the nutrition status of the patient.

16. Develop a preoperative and postoperative plan of care for the patient undergoing gastric surgery.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Bleeding Ulcer, Pathophysiology

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Gastritis

Pathophysiology

Types of Gastritis

Type A (nonerosive) chronic gastritis refers to an inflammation of the glands, as well as the fundus and body of the stomach. Type B chronic gastritis usually affects the glands of the antrum but may involve the entire stomach. In atrophic chronic gastritis, diffuse inflammation and destruction of deeply located glands accompany the condition. Chronic atrophic gastritis affects all layers of the stomach, thus decreasing the number of cells. The muscle thickens, and inflammation is present. Chronic atrophic gastritis is characterized by total loss of fundal glands, minimal inflammation, thinning of the gastric mucosa, and intestinal metaplasia (abnormal tissue development). These cellular changes can lead to peptic ulcer disease (PUD) and gastric cancer (McCance et al., 2010).

Etiology and Genetic Risk

Chronic Gastritis

Type A gastritis has been associated with the presence of antibodies to parietal cells and intrinsic factor. Therefore an autoimmune cause for this type of gastritis is likely. Parietal cell antibodies have been found in most patients with pernicious anemia and in more than one half of those with type A gastritis. A genetic link to this disease, with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, has been found in the relatives of patients with pernicious anemia (McCance et al., 2010).

The most common form of the disease is type B gastritis, caused by H. pylori infection. A direct correlation exists between the number of organisms and the degree of cellular abnormality present. The host response to the H. pylori infection is activation of lymphocytes and neutrophils. Release of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-1, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha, damages the gastric mucosa (McCance et al., 2010).

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Gastritis is a very common health problem in the United States. Yet, a balanced diet, regular exercise, and stress-reduction techniques can help prevent it (Chart 58-1). A balanced diet includes following the recommendations of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and limiting intake of foods and spices that can cause gastric distress, such as caffeine, chocolate, mustard, pepper, and other strong or hot spices. Alcohol and tobacco consumption should also be avoided. Regular exercise maintains peristalsis, which helps prevent gastric contents from irritating the gastric mucosa. Stress-reduction techniques can include aerobic exercise, meditation, reading, and/or yoga, depending on individual preferences. Psychotherapy may also be considered.

Chart 58-1 Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Gastritis Prevention

• Avoid drinking excessive amounts of alcoholic beverages.

• Use caution in taking large doses of aspirin, other NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen), and corticosteroids.

• Avoid excessive intake of caffeine-containing beverages, especially coffee and tea.

• Be sure that foods and water are safe, to avoid contamination.

• Manage stress levels using complementary and alternative therapies, such as relaxation and meditation techniques.

• Protect yourself against exposure to toxic substances in the workplace, such as lead and nickel.

• Seek medical treatment if you are experiencing symptoms of esophageal reflux (see Chapter 57).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Symptoms of acute gastritis range from mild to severe. The patient may report epigastric discomfort, anorexia, cramping, nausea, and vomiting (Chart 58-2). Assess for abdominal tenderness and bloating, hematemesis (vomiting blood), or melena (traces of blood in the stool). Symptoms last only a few hours or days and vary with the cause. Aspirin/NSAID–related gastritis may result in dyspepsia (heartburn). Gastritis or food poisoning caused by endotoxins, such as staphylococcal endotoxin, has an abrupt onset. Severe nausea and vomiting often occur within 5 hours of ingestion of the contaminated food. In some cases, gastric hemorrhage is the presenting symptom, which is a life-threatening emergency.

Gastritis

Chronic gastritis causes few symptoms unless ulceration occurs. Patients may report nausea, vomiting, or upper abdominal discomfort. Periodic epigastric pain may occur after a meal. Some patients have anorexia (see Chart 58-2).

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) via an endoscope with biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing gastritis. The physician takes a biopsy to establish a definitive diagnosis of the type of gastritis. If lesions are patchy and diffuse, biopsy of several suspicious areas may be necessary to avoid misdiagnosis. A cytologic examination of the biopsy specimen is performed to confirm or rule out gastric cancer. Tissue samples can also be taken to detect H. pylori using rapid urease testing. As the name implies, this test provides quick results unlike the more traditional tissue culture that takes several weeks to determine if the bacteria are present. The results of these tests are more reliable if the patient has discontinued taking antacids for at least a week (Pagana & Pagana, 2010).

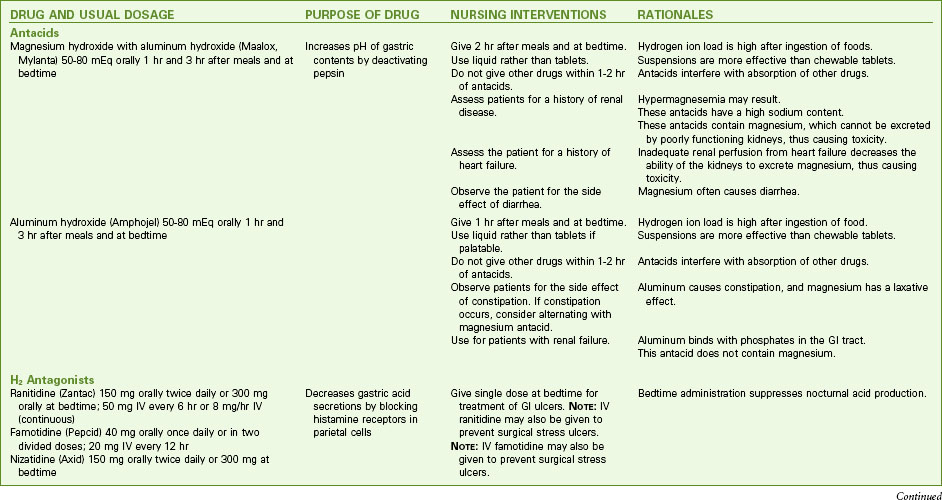

Interventions

H2-receptor antagonists, such as famotidine (Pepcid) and nizatidine (Axid), are typically used to block gastric secretions. Sucralfate (Carafate, Sulcrate ![]() ), a mucosal barrier fortifier, may also be prescribed. Antacids used as buffering agents include aluminum hydroxide combined with magnesium hydroxide (Maalox) and aluminum hydroxide combined with simethicone and magnesium hydroxide (Mylanta). Antisecretory agents (proton pump inhibitors [PPIs]) such as omeprazole (Prilosec) or pantoprazole (Protonix) may be prescribed to suppress gastric acid secretion (Chart 58-3).

), a mucosal barrier fortifier, may also be prescribed. Antacids used as buffering agents include aluminum hydroxide combined with magnesium hydroxide (Maalox) and aluminum hydroxide combined with simethicone and magnesium hydroxide (Mylanta). Antisecretory agents (proton pump inhibitors [PPIs]) such as omeprazole (Prilosec) or pantoprazole (Protonix) may be prescribed to suppress gastric acid secretion (Chart 58-3).

Drug Alert

Assist the patient with various techniques that reduce stress and discomfort, such as progressive relaxation, cutaneous stimulation, guided imagery, and distraction. Other complementary and alternative therapies that have been used are listed in Table 58-1. Chapter 2 describes these therapies in detail.

TABLE 58-1 COMMONLY USED COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES FOR GASTRITIS AND PEPTIC ULCER DISEASE (PUD)

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Peptic Ulcer Disease

Pathophysiology

Types of Ulcers

Three types of ulcers may occur: gastric ulcers, duodenal ulcers, and stress ulcers (less common). Most gastric and duodenal ulcers are caused by H. pylori infection, which is transmitted via the fecal-oral route and thought to be acquired in childhood. It can also be transmitted from contaminated endoscopic equipment (Pagana & Pagana, 2010). About half of the world’s population is infected with the bacterium (Fromm, 2009).

As a response to the bacteria, cytokines, neutrophils, and other substances are activated and cause epithelial cell necrosis. Urease, a substance secreted by the H. pylori bacterium, produces ammonia and creates a more alkaline environment (McCance et al., 2010). Hydrogen ions are then released in response to the presence of ammonia and contribute further to mucosal damage. Urease can be detected through laboratory testing to confirm the H. pylori infection.

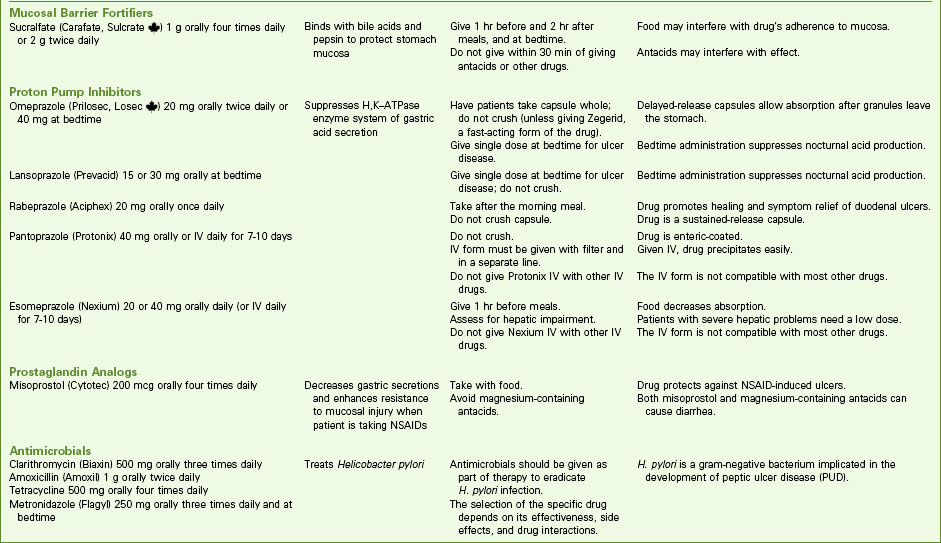

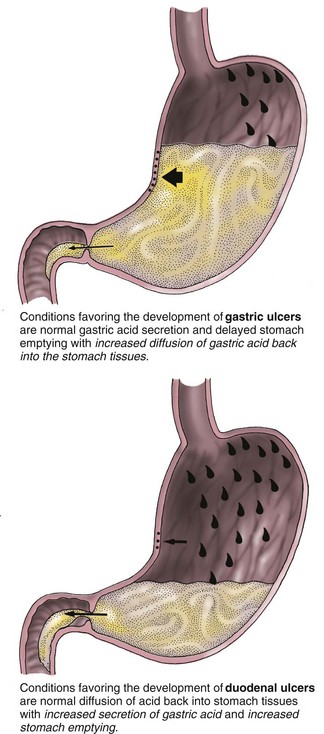

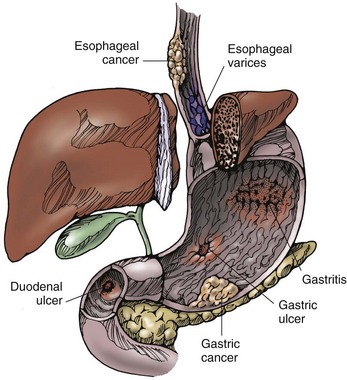

Gastric ulcers usually develop in the antrum of the stomach near acid-secreting mucosa. When a break in the mucosal barrier occurs (such as that caused by H. pylori infection), hydrochloric acid injures the epithelium. Gastric ulcers may then result from back-diffusion of acid or dysfunction of the pyloric sphincter (Fig. 58-1). Without normal functioning of the pyloric sphincter, bile refluxes (backs up) into the stomach. This reflux of bile acids may break the integrity of the mucosal barrier and produce hydrogen ion back-diffusion, which leads to mucosal inflammation. Toxic agents and bile then destroy the membrane of the gastric mucosa.

Gastric emptying is often delayed in patients with gastric ulceration. This causes regurgitation of duodenal contents, which worsens the gastric mucosal injury. Decreased blood flow to the gastric mucosa may also alter the defense barrier and thereby allow ulceration to occur. Gastric ulcers are deep and penetrating, and they usually occur on the lesser curvature of the stomach, near the pylorus (Fig. 58-2).

The main feature of a duodenal ulcer is high gastric acid secretion, although a wide range of secretory levels is found. In patients with duodenal ulcers, pH levels are low (excess acid) in the duodenum for long periods. Protein-rich meals, calcium, and vagus nerve excitation stimulate acid secretion. Combined with hypersecretion, a rapid emptying of food from the stomach reduces the buffering effect of food and delivers a large acid bolus to the duodenum (see Fig. 58-1). Inhibitory secretory mechanisms and pancreatic secretion may be insufficient to control the acid load.

Complications of Ulcers

The most common complications of PUD are hemorrhage, perforation, pyloric obstruction, and intractable disease. Hemorrhage is the most serious complication (Fig. 58-3). It tends to occur more often in patients with gastric ulcers and in older adults. Many patients have a second episode of bleeding if underlying infection with H. pylori remains untreated or if therapy does not include an H2 antagonist. With massive bleeding, the patient vomits bright red or coffee-ground blood (hematemesis). Hematemesis usually indicates bleeding at or above the duodenojejunal junction (upper GI bleeding) (Chart 58-4).

Upper GI Bleeding

Etiology and Genetic Risk

Certain substances may contribute to gastroduodenal ulceration by altering gastric secretion, producing localized damage to mucosa and interfering with the healing process. For example, corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone), theophylline (Theo-Dur), and caffeine stimulate hydrochloric acid production. Patients receiving radiation therapy may also develop GI ulcers. Other risk factors for PUD are the same as for gastritis (see Chart 58-1).

Genetic factors may be important. H. pylori infection tends to occur in people who are genetically susceptible. Those with a family history of PUD are at higher risk for having PUD than those without a family history (McCance et al., 2010).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Dyspepsia (indigestion) is the most commonly reported symptom associated with PUD. It is typically described as sharp, burning, or gnawing. Some patients may perceive discomfort as a sensation of abdominal pressure or of fullness or hunger. Specific differences between gastric and duodenal ulcers are listed in Table 58-2.

TABLE 58-2 DIFFERENTIAL FEATURES OF GASTRIC AND DUODENAL ULCERS

| FEATURE | GASTRIC ULCER | DUODENAL ULCER |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Usually 50 yr or older | Usually 50 yr or older |

| Gender | Male/female ratio of 1.1 : 1 | Male/female ratio of 1 : 1 |

| Blood group | No differentiation | Most often type O |

| General nourishment | May be malnourished | Usually well nourished |

| Stomach acid production | Normal secretion or hyposecretion | Hypersecretion |

| Occurrence | Mucosa exposed to acid-pepsin secretion | Mucosa exposed to acid-pepsin secretion |

| Clinical course | Healing and recurrence | Healing and recurrence |

| Pain | Occurs 30-60 min after a meal; at night: rarely Worsened by ingestion of food | Occurs  -3 hr after a meal; at night: often awakens patient between 1 and 2 AM -3 hr after a meal; at night: often awakens patient between 1 and 2 AMRelieved by ingestion of food |

| Response to treatment | Healing with appropriate therapy | Healing with appropriate therapy |

| Hemorrhage | Hematemesis more common than melena | Melena more common than hematemesis |

| Malignant change | Perhaps in less than 10% | Rare |

| Recurrence | Tends to heal, and recurs often in the same location | 60% recur within 1 yr; 90% recur within 2 yr |

| Surrounding mucosa | Atrophic gastritis | No gastritis |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree