Chapter 27 Care of Patients with Skin Problems

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Use principles of infection control to prevent transmission when caring for a patient with a skin infection.

2. Supervise skin care delegated to licensed practical nurses/licensed vocational nurses (LPNs/LVNs) or unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP).

3. Teach the patient with mobility problems and his or her caregivers how to reduce and relieve skin pressure in the home environment.

4. Ensure that the skin of incontinent patients is kept clean and dry.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

5. Use appropriate risk assessment tools to perform a focused skin assessment and re-assessment to determine risk for pressure ulcer development and adequacy of the skin’s protective functions.

6. Teach all people how to perform thorough skin self–examination (TSSE) to monitor for skin cancer.

7. Teach all people ways to reduce risk for skin cancer.

8. Instruct the patient with a skin infection and his or her caregivers how to avoid spreading the infection.

9. Assess the ability of the patient with a skin problem to see and reach the affected area and care for the problem.

10. Assess the patient’s and family’s feelings about a chronic skin condition or visible scar.

11. Support the patient and family in coping with changes in skin integrity and in body image.

12. Encourage the patient with a visible wound or other skin problem to participate in the care of the wound.

13. Compare wound healing by first, second, and third intention.

14. Evaluate wounds for size, depth, presence of infection, and indications of healing.

15. Differentiate the manifestations for these pressure ulcer categories: stage 1 through stage 4, unstageable ulcers, and suspected deep tissue injury.

16. Coordinate with the health care team to plan an individualized strategy for pressure ulcer prevention for a specific patient at increased risk.

17. Identify the key features of psoriasis.

18. Coordinate nursing interventions for care of the patient with psoriasis in the community.

19. Identify key features of melanoma and other skin cancers.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

As discussed in Chapter 26, the skin plays an important role in protection. Like the wall surrounding a castle, it provides a strong barrier, in this case to invasion by harmful microorganisms.

Minor Skin Irritations

Dryness

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Nursing interventions focus on teaching the patient and family how to maintain healthy skin, rehydrate the outer skin layers, and relieve itching. Chart 27-1 lists practical ways to avoid overdrying the skin. Remind the patient that bathing with moisturizing soaps, oils, and lotions may reduce dryness. Some soaps and body washes, especially those described as “antimicrobial” and those with perfumes and other scents, may make dry skin worse. Limiting the use of soap to soiled or skinfold areas can also reduce dryness. A 20-minute soak in a warm bath, followed by application of an emollient cream or lotion, will help rehydrate the skin and reduce itching. If the patient cannot take a tub bath, teach him or her to wrap the trunk and extremities in warm, moist towels covered by plastic sheeting or a clean garbage bag for 15 to 20 minutes before applying moisturizers. Skin creams or lotions are more effective when applied to slightly damp skin within 2 to 3 minutes after bathing.

Chart 27-1 Patient and Family Education

Preparing For Self-Management: Prevention of Dry Skin

• Use a room humidifier during the winter months or whenever the furnace is in use.

• Take a complete bath or shower only every other day (wash face, axillae, perineum, and any soiled areas with soap daily).

• Use a superfatted, nonalkaline soap instead of deodorant soap.

• Rinse the soap thoroughly from your skin.

• If you like bath oil, add the oil to the water at the end of the bath.

• Take care to avoid falls; oil makes the tub slippery.

• Pat rather than rub skin surfaces dry.

• Avoid clothing that continuously rubs the skin, such as tight belts, nylon stockings, or pantyhose.

• Maintain a daily fluid intake of 3000 mL unless contraindicated for another medical condition.

• Do not apply rubbing alcohol, astringents, or other drying agents to the skin.

Pruritus

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Plan care to promote comfort and prevent disruption of skin integrity that can result from vigorous scratching. Because dry skin worsens itching, emphasize proper bathing and skin moisturizing techniques (see Chart 27-1). Encourage patients to keep the fingernails trimmed short, with rough edges filed to reduce skin damage from scratching and to prevent secondary infection. Tell patients that wearing mittens or splints at night can help prevent inadvertent scratching during sleep. If the patient cannot perform self-care, teach the family (for home care) and unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) to trim the patient’s fingernails and apply mittens or gloves. As always, be sure to stress the importance of not breaking the skin or digging into nail corners when trimming the nails of patients with diabetes.

Urticaria

Health Promotion and Maintenance

A. “Wear long-legged pajamas to sleep in rather than nightgowns.”

B. “Avoid wearing pantyhose or nylon stockings for more than 2 hours at a time.”

C. “Leave the fat-containing soap on your skin when bathing rather than rinsing it off.”

D. “Bathe in water that is as warm as you can stand to stimulate the release of body oils from your sebaceous glands.”

Trauma

Pathophysiology

Phases of Wound Healing

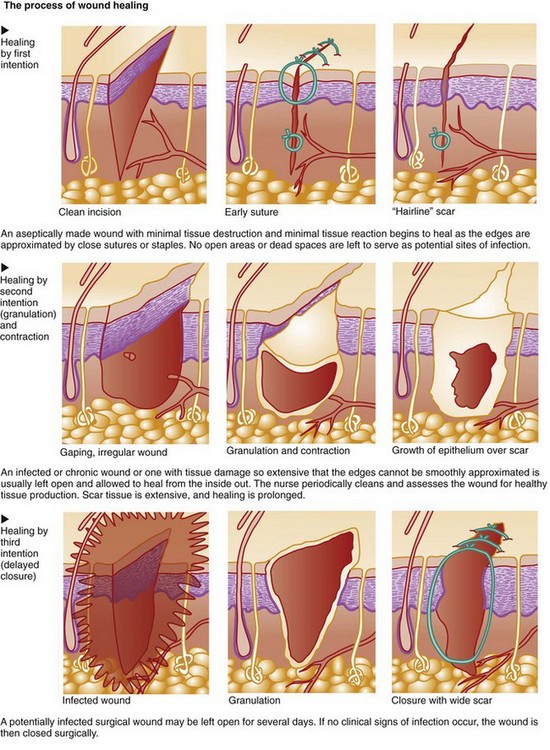

Wound healing occurs in three phases: the inflammatory (lag) phase, the proliferative (connective tissue repair) phase, and the maturation (remodeling) phase. Table 27-1 lists the key events of normal wound healing. The length of each phase depends on the type of injury, the patient’s overall health status, and whether the wound is healing by first, second, or third intention (Fig. 27-1).

TABLE 27-1 NORMAL WOUND HEALING

Wounds at high risk for infection, such as surgical incisions that enter a nonsterile body cavity or traumatic wounds that occur under unclean conditions, may be intentionally left open for several days. After debris (dead cells and tissues) and exudate have been removed (débrided) and inflammation has subsided, the wound is closed by first intention. This type of healing involves delayed primary closure (third intention) and results in a scar similar to that found in wounds that heal by first intention. Healing can be impaired by many factors (Table 27-2).

TABLE 27-2 CAUSES OF IMPAIRED WOUND HEALING

| CAUSE | MECHANISM |

|---|---|

| Altered Inflammatory Response | |

| Local | |

| Reduced local tissue circulation, resulting in ischemia, impaired leukocytic response to wounding, and increased probability of wound infection | |

| Systemic | |

| Systemic inhibition of leukocytic response, resulting in impaired host resistance to infection | |

| Impaired Cellular Proliferation | |

| Local | |

| Prolonged inflammatory response, which can result in low tissue oxygen tension and further tissue destruction | |

| Systemic | |

| Impaired cellular proliferation and collagen synthesis Decreased wound contraction | |

Mechanisms of Wound Healing

Partial-Thickness Wounds

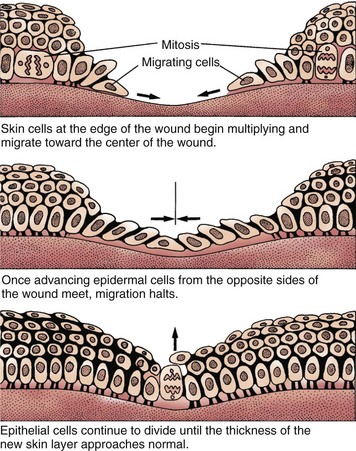

Partial-thickness wounds are more superficial, involving damage to the epidermis and upper layers of the dermis. These wounds heal by re-epithelialization, the production of new skin cells by undamaged epidermal cells in the basal layer of the dermis, which also lines the hair follicles and sweat glands (Fig. 27-2). Skin injury is followed immediately by local inflammation. The inflammatory response causes the formation of a fibrin clot and the release of growth factors that stimulate epidermal cell division (mitosis). New skin cells move into open spaces on the wound surface, where the fibrin clot acts as a frame or scaffold to guide cell movement. Regrowth across the open area (resurfacing) is only one cell layer thick at first. As healing continues, the cell layer thickens and stratifies (forms layers) to resemble normal skin. A healed wound re-establishes the protective barrier properties of the skin with keratin production.

Full-Thickness Wounds

Some of these fibroblasts act like smooth muscle cells and begin to pull the wound edges inward along the path of least resistance (contraction) (see Fig. 27-1). This causes the wound to decrease in size at a uniform rate of about 0.6 to 0.75 mm/day. Complete closure of a wound by contraction depends on the mobility of the surrounding skin as tension is applied to it. If tension in the surrounding skin exceeds the counterforce of wound contraction, healing will be delayed until undamaged epidermal cells at the wound edges can bridge the defect. Unlike re-epithelialization in partial-thickness wounds, which results in the return of a near-normal epithelial barrier, the bridging of epithelial cells across a large area of granulation tissue results in an unstable barrier. A venous leg ulcer is one example of a skin defect that heals poorly by contraction. Re-epithelialization of these chronic wounds often results in a thin epidermal barrier that is easily re-injured.

Re-epithelialization, granulation, and contraction do not continue indefinitely. Natural healing processes can slow down and even stop in the presence of infection, unrelieved pressure, or mechanical obstacles. For example, dead tissue not only supports the overgrowth of organisms but also obstructs collagen deposition and wound contraction. Therefore thorough wound débridement is necessary for healing to occur. In the case of chronic wounds, healing may cease spontaneously and without an obvious cause. In addition, infection in chronic wounds may not show the expected manifestations. Often the only manifestation is an increase in wound size or failure of the wound to decrease in size (Broderick, 2009).

Considerations for Older Adults

As skin ages, the process of wound healing becomes less efficient. Both re-epithelialization and wound contraction slow, and replacement of connective tissue is reduced. Thus the strength of a healed wound in an older adult is reduced and the area is at greater risk for re-injury. When aging skin is further hindered from healing by inadequate nutrition, incontinence, or immobility, any wound in an older adult has a high risk for becoming a chronic wound. Although prevention strategies provide the best outcome, aggressive treatment of any degree of loss of skin integrity, no matter how small, should be started as soon as it is discovered in an older adult (Bianchi & Cameron, 2008; Touhy & Jett, 2010).

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Management of skin trauma varies with the depth and type of injury. The collaborative management for any type of skin trauma focuses on enhancing wound healing, preventing infection, and restoring function to the area. Effective management of pressure ulcers or of burns includes interventions that support a healing environment (see Chapter 28).

Pressure Ulcers

Pathophysiology

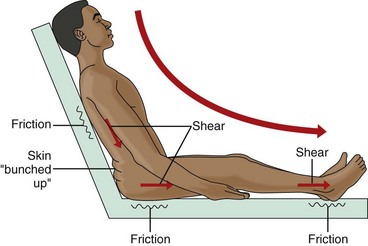

Other factors increase the risk for pressure ulcer formation. Friction and shear are mechanical forces that impair skin integrity and set the stage for skin breakdown. Excessive skin moisture, such as urinary or fecal incontinence, increases the risk for skin damage when external mechanical forces are applied. Nutritional status is also an important concern. Protein malnutrition not only makes normal tissue more prone to breakdown but also delays healing (Slachta, 2008).

Mechanical Forces

Shear or shearing forces are generated when the skin itself is stationary and the tissues below the skin (e.g., fat, muscle) shift or move (Fig. 27-3). The movement of the deeper tissue layers reduces the blood supply to the skin, leading to skin hypoxia, anoxia, ischemia, inflammation, and necrosis.

Incidence/Prevalence

Pressure ulcer development is a problem found among patients in the acute care setting, long-term care facility, and home care setting. Although patient care has improved in many ways and new products are available for prevention and treatment, 3% to 14% of hospitalized patients still experience pressure ulcer formation (Dunleavy, 2008).

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Pressure ulcers can be prevented if the risk is recognized and intervention begins early (Chart 27-2) (Ackerman, 2011). Key health care team members for pressure ulcer prevention and management are the certified wound care specialist and the dietitian.

Chart 27-2 Best Practice For Patient Safety & Quality Care

Preventing Pressure Ulcers

Positioning

• Pad contact surfaces with foam, silicon gel, air pads, or other pressure-relieving pads.

• Do not keep the head of the bed elevated above 30 degrees to prevent shearing.

• Use a lift sheet to move a patient in the bed. Avoid dragging or sliding him or her.

• When positioning a patient on his or her side, do not position directly on the trochanter.

• Reposition an immobile patient at least every 2 hours while in bed and at least every 1 hour while sitting in a chair.

• Do not place a rubber ring or donut under the patient’s sacral area.

• When moving an immobile patient from a bed to another surface, use a designated slide board well lubricated with talc or use a mechanical lift.

• Place pillows or foam wedges between two bony surfaces.

• Keep the patient’s skin directly off plastic surfaces.

• Keep the patient’s heels off the bed surface using bed pillow under ankles.

Skin Care

Skin Cleaning

• Clean the skin as soon as possible after soiling occurs and at routine intervals.

• Use a mild, heavily fatted soap or gentle commercial cleanser for incontinence.

• Use tepid rather than hot water.

• In the perineal area, use a disposable cleaning cloth that contains a skin barrier agent.

• While cleaning, use the minimum scrubbing force necessary to remove soil.

• Gently pat rather than rub the skin dry.

• Do not use powders or talcs directly on the perineum.

• After cleansing, apply a commercial skin barrier to those areas in frequent contact with urine or feces.

A pressure ulcer prevention program consists of two steps: (1) early identification of high-risk patients, and (2) implementation of aggressive intervention for prevention with the use of pressure-relief or pressure-reduction devices. Pressure mapping is a method for identifying specific anatomic areas at risk for breakdown and planning interventions for patients who are bedridden or wheelchair bound. The process of pressure mapping involves the use of a computerized tool that measures pressure distribution for a person sitting in a chair or lying on a mattress (Hanson et al., 2007). The map is displayed as colored areas on the computer screen based on temperature differences. Shades of red indicate areas of greater heat production and are associated with increased pressure loads. Shades of blue indicate cooler areas under lower pressure. When used in combination with more traditional risk assessment tools, pressure mapping appears to help identify problem areas before visual changes occur and allows for more targeted prevention strategies.

Effective risk identification and prevention measures include education of the patient and the caregiver. Documentation of risk assessment, implementation of prevention measures, and education of all people involved in the care of the patient at risk for pressure ulcer formation are key to the plan’s success (Dunleavy, 2008). Periodic re-assessment of risk and continuing evaluation are critical, especially when the patient’s condition changes.

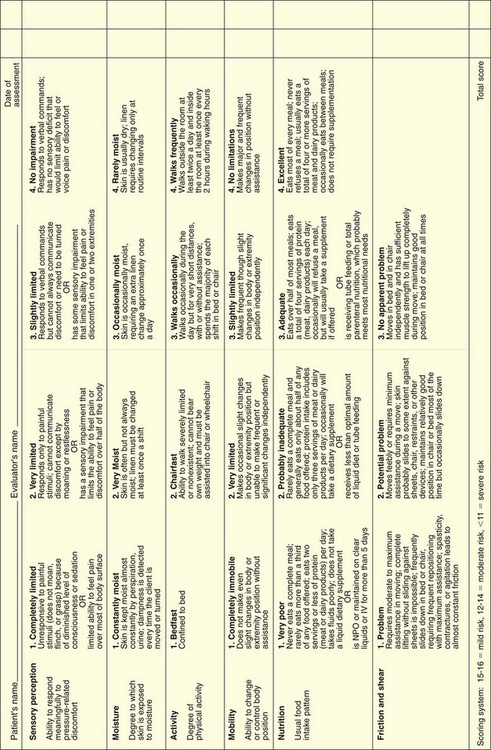

Identification of High-Risk Patients

As suggested by The Joint Commission’s National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs), all patients admitted to a health care facility or home care agency should be assessed for pressure ulcer risk. The use of a risk assessment tool increases the chances of identifying those patients at greater risk for skin breakdown. The Braden Scale (Fig. 27-4) is the most commonly used skin risk assessment tool. This validated tool helps the nurse assess and document the various risk categories for pressure ulcer formation including mental status, activity and mobility, nutritional status, and incontinence.

FIG. 27-4 The Braden Scale for predicting pressure ulcer risk. IV, Intravenous; NPO, nothing by mouth.

Nutritional status is a critical risk factor for pressure ulcer development and for successful healing (Slachta, 2008). Intact skin and wound healing depend on a positive nitrogen balance and adequate serum protein levels. The patient in negative nitrogen balance not only heals more slowly but also is at greater risk for accelerated tissue destruction. Draining wounds contribute to protein loss and require more aggressive intervention.

Nutritional status assessment includes laboratory studies; evaluation of weight and recent weight change; ability of the patient to consume an adequate diet; and the need for vitamin, mineral, or protein supplementation. Serum albumin and prealbumin levels are often used to monitor nutritional status. Prealbumin is a more sensitive marker because it has a shorter half-life. Nutrition is considered inadequate when the serum albumin level is less than 3.5 g/dL, the prealbumin level is less than 19.5 mg/dL, or the lymphocyte count is less than 1800/mm3. However, serum protein levels are affected by a number of other factors including level of hydration, metabolic stress, and infection. Therefore laboratory values are valuable only when supported by additional assessment information. Other indicators of inadequate nutrition include poor daily intake of food and fluids with a weight loss greater than 5% change in 30 days or greater than 10% change in 180 days (Dorner et al., 2009).

Action Alert

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Pressure-Relieving and Pressure-Reducing Techniques

• Prevention of skin breakdown because they cannot turn (e.g., immobility, loss of sensation)

• Prevention of extension of skin breakdown that has already occurred

• Promotion of healing for breakdown present on several turning surfaces

Frequent repositioning of bedbound patients, as described in Chart 27-2, is critical in reducing pressure over bony prominences. A good plan for positioning is the 30-degree rule. This plan ensures that the patient is positioned and propped so that whatever part of the body is elevated is tilted back at least a 30-degree angle to the mattress rather than resting directly on a dependent bony prominence. This rule applies to side-lying as well as head-of-bed elevation positions. The patient who requires greater head elevation because of respiratory difficulties should be tilted forward more than 30 degrees with pillows behind the back to keep pressure off of the sacral/coccyx area. Often positioning is delegated to UAP. Teach UAP the importance of proper positioning, and demonstrate how to perform it. Also teach family members to use these techniques in the home.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Wound Assessment

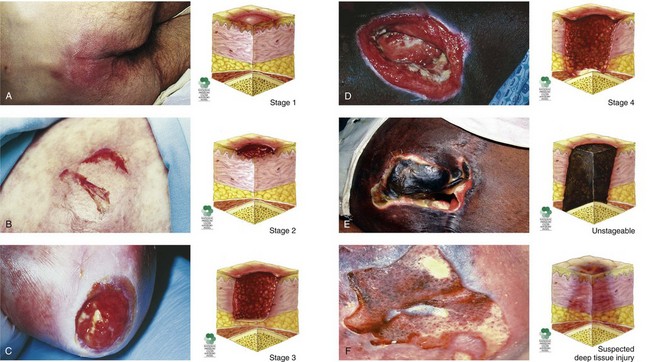

The appearance of pressure ulcers changes with the depth of the injury. Chart 27-3 lists the features of the six categories or stages of pressure ulceration, and Fig. 27-5 shows examples.

Key Features

Pressure Ulcers

Suspected Deep Tissue Injury

• The intact skin area appears purple or maroon.

• Blood-filled blisters may be present.

• Before the above-listed changes appeared, the tissue in this area may first have been painful.

• Other changes that may have preceded the discoloration include that the area may have felt more firm, boggy, mushy, warmer, or cooler than the surrounding tissue.

Stage 1

• Area, usually over a bony prominence, is red and does not blanch with external pressure.

• For patients with darker skin that does not blanch:

• The ulcer appears as a defined area of persistent redness in lightly pigmented skin, whereas in darker skin tones, the ulcer may appear with persistent red, blue, or purple hues.

Stage 3

• Skin loss is full thickness.

• Subcutaneous tissues may be damaged or necrotic.

• Damage extends down to but not through the underlying fascia; bone, tendon, and muscle are not exposed.

• The depth can vary with anatomic location; areas of thin skin (e.g., the bridge of the nose) may show only a shallow crater, whereas thicker tissue areas with larger amounts of subcutaneous fat may show a deep, crater-like appearance.

Data from National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP). (2010, January). Updated staging system. Retrieved October 2010, from www.npuap.org.

Record the location and size of the wound first. Wounds are sized by length, width, and depth using millimeters or centimeters. In standardizing wound size for documentation and communication purposes, assess the wound as a clock face with the 12 o’clock position in the direction of the patient’s head and the 6 o’clock position in the direction of the patient’s feet. Always measure the length from the 12 o’clock position to the 6 o’clock position and the width between the 9 o’clock position and the 3 o’clock position. Measure depth as the distance from the deepest portion of the wound base to the skin level. Use disposable paper tape measures to obtain the length and width of a wound. Touch the bottom of the wound with a cotton-tipped applicator or swab and mark the place on the swab that is level with the skin surface to obtain wound depth. Then measure the area of the swab between the tip and the mark. When all caregivers use this format, measurement is accurate and wound progress can be determined (Hanson et al., 2007).

In the early stages of wound healing, the eschar is dry, leathery, and firmly attached to the wound surface. As the inflammatory phase of wound healing begins and removal of wound debris progresses, the eschar starts to lift and separate from the tissue beneath. This nonliving eschar is a good breeding ground for bacteria normally found on the skin surface, as well as those introduced by incontinence or other means. As bacteria increase, they release enzymes that soften necrotic tissue. This tissue becomes softer and more yellow. In the presence of bacterial colonization, wound exudate increases substantially; the color and odor of wound exudate indicate the major organism present. The features of wound exudate are listed in Table 27-3.

TABLE 27-3 TYPES OF WOUND EXUDATE

| CHARACTERISTICS | SIGNIFICANCE |

|---|---|

| Serosanguineous Exudate | |

| Blood-tinged amber fluid consisting of serum and red blood cells | Normal for first 48 hr after injury Sudden increase in amount precedes wound dehiscence in wounds closed by first intention |

| Purulent Exudate | |

| Creamy yellow pus | Colonization with Staphylococcus |

| Greenish blue pus causing staining of dressings and accompanied by a “fruity” odor | Colonization with Pseudomonas |

| Beige pus with a “fishy” odor | Colonization with Proteus |

| Brownish pus with a “fecal” odor | Colonization with aerobic coliform and Bacteroides (usually occurs after intestinal surgery) |

Other Diagnostic Assessment

Patient-Centered Care; Evidence-Based Practice; Safety

1. What risk factors does this patient have for pressure ulcer development? Explain how the identified factors increase his risk.

2. What additional assessment data should you obtain?

3. Given his diagnosis, in what position do you expect to place him? Does this position increase or decrease his risk for pressure ulcer formation? If so, where is/are the ulcer(s) likely to develop?

4. At 220 pounds, is he likely to have adequate nutrition? Why or why not?

Planning and Implementation

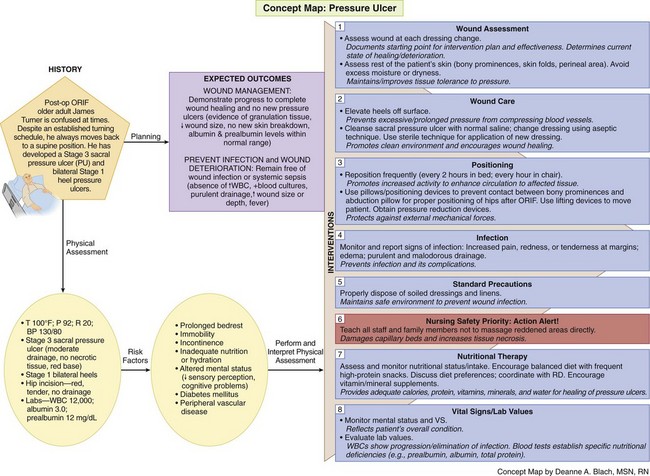

The Concept Map on p. 484 addresses care issues related to patients who have or are at risk for pressure ulcers.

Managing Wounds

Interventions

Nonsurgical Management

General interventions for pressure ulcer care are listed in Chart 27-4. Nonsurgical intervention of pressure ulcers is often left to the discretion of the nurse, who coordinates with the health care provider and certified wound care specialist (if available) to select a method of wound dressing on the basis of the identified goal of wound management. Many agencies have guidelines or protocols for wound dressings based, for example, on wound size and depth and presence of drainage.

Chart 27-4 Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

Wound Management of Pressure Ulcers

• If ulcer is covered, remove old dressings/coverings daily (unless the dressing type is to remain in place until it loosens naturally).

• Measure wound size at greatest length and width using a disposable paper tape measure or, for asymmetric ulcers, by tracing the wound onto a piece of plastic film of sheeting (plastic template) at least daily.

• Compare all subsequent measurements against the initial measurement.

• Assess the ulcer for presence of necrotic tissue and amount of exudates.

• Assess and document the condition of the skin surrounding the pressure ulcer in terms of color, temperature, texture, moisture, and appearance.

• Remove or trim loose bits of tissue (may be done by a certified wound care specialist, physical therapist, advanced practice nurse, or other as specified by the agency and the state’s nurse practice act).

• Cleanse the ulcer with saline or a prescribed solution (after diluting it as per manufacturer’s directions or prescriber’s instructions).

• Rinse and dry the ulcer surface.

• In collaboration with the certified wound care specialist, select and apply the dressing materials most appropriate for the volume of wound drainage.

• If possible, avoid positioning the patient on the pressure ulcer.

• Re-position at least every 1 to 2 hours to prevent ulcer extension or generation of additional pressure ulcers.

• Use prescribed pressure-relieving and pressure-reducing devices and techniques as described in Chart 27-2.

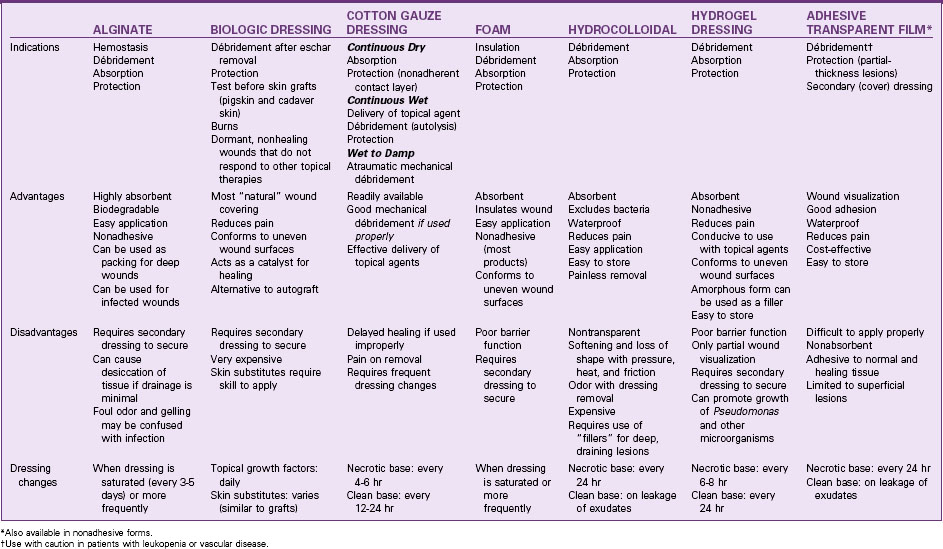

A properly designed dressing can speed healing by removing unwanted debris from the ulcer surface, protecting exposed healthy tissues, and creating a barrier between the body and the environment until the ulcer is closed. For a patient with a draining, necrotic ulcer, the dressing must also remove excessive exudate and loose debris without damaging epithelial cells or newly formed granulation tissue. If necrosis is extensive and the eschar is thick, dead tissue must be surgically or chemically removed before further débridement with dressings can be effective. Depending on the dressing material used, dressings help remove debris either through mechanical débridement (mechanical entrapment and detachment of dead tissue), topical chemical débridement (enzyme preparations applied topically to loosen necrotic tissue), or by natural chemical débridement (creating an environment that promotes self-digestion of dead tissues by naturally-occurring bacterial enzymes [autolysis]) (Table 27-4).

TABLE 27-4 COMMON DRESSING TECHNIQUES FOR WOUND DÉBRIDEMENT

| TECHNIQUE | MECHANISM OF ACTION |

|---|---|

| Wet-to-damp saline-moistened gauze | As with the wet-to-dry technique, necrotic debris is mechanically removed but with less trauma to healing tissue. |

| Continuous wet gauze | The wound surface is continually bathed with a wetting agent of choice, promoting dilution of viscous exudate and softening of dry eschar. |

| Topical enzyme preparations | Proteolytic action on thick, adherent eschar causes breakdown of denatured protein and more rapid separation of necrotic tissue. |

| Moisture-retentive dressing | Spontaneous separation of necrotic tissue is promoted by autolysis. |

• A hydrophobic (nonabsorbent, waterproof) material is useful when the wound is relatively free of drainage and the purpose is to protect the ulcer from external contamination.

• A hydrophilic (absorbent) material draws excessive drainage away from the ulcer surface, preventing maceration.

A variety of synthetic materials with different absorbent properties are available (Table 27-5). Unlike cotton gauze dressings, these may be left intact for extended periods. Biologic and synthetic skin substitutes are available that can also prevent tissue dehydration and promote healing (see Chapter 28). However, the use of these products for chronic wounds is often cost prohibitive.

Action Alert

Change synthetic dressings when exudate causes the adhesive seal to break and leakage to occur.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree