Chapter 45 Care of Patients with Problems of the Central Nervous System

The Spinal Cord

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Develop a teaching plan to educate the patient on ways to prevent back and neck pain, including the need for ergonomics in the workplace.

2. Prioritize the nursing care of the patient with a spinal cord injury (SCI).

3. Explain the importance of collaborating with the health care team when providing care for patients with SCI.

4. Plan how to integrate advance directives in the plan of care for patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with respect to the patient’s wishes.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

5. Identify community resources for patients with spinal cord health problems and their families.

6. In collaboration with the health care team, develop a discharge plan for the patient and family after a lumbar or cervical laminectomy.

7. Describe the need to counsel patients with SCI and their partners on sexuality issues as needed.

8. Describe the impact of spinal cord health problems on patients and their families.

9. Perform a comprehensive health assessment of the patient with a spinal cord injury.

10. Assess the patient with spinal cord health problems for mobility, gait, strength, and sensation.

11. Plan interventions to prevent complications of immobility when caring for the patient with spinal cord health problems.

12. Identify precautions to prevent injury when moving a patient with a spinal cord problem.

13. Apply knowledge of pathophysiology when caring for a patient having autonomic dysreflexia.

14. Explain the clinical manifestations and management options associated with spinal cord tumors.

15. Explain the pathophysiology of multiple sclerosis (MS) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

16. Explain the role of drug therapy in managing patients with spinal cord problems.

17. Develop a postoperative plan of care for patients having spinal cord surgery, including monitoring for complications.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Spinal Cord Structure

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Concept Map: Multiple Sclerosis

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Back Pain

Lumbosacral Back Pain (Low Back Pain)

Pathophysiology

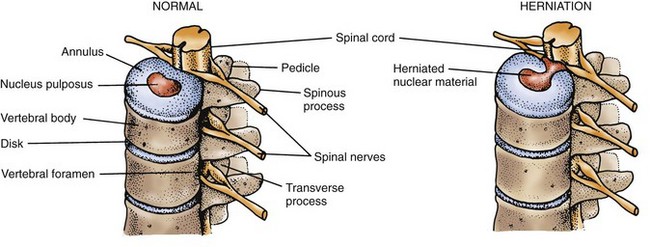

Lumbosacral back pain, referred to as low back pain (LBP), is more common than cervical pain. Acute pain is caused by muscle strain or spasm, ligament sprain, disk (also spelled “disc”) degeneration (osteoarthritis), or herniation of the nucleus pulposus from the center of the disk. Herniated disks occur most often between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae (L4-5) but may occur at other levels. A bulging or herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP) in the lumbosacral area can press on the adjacent spinal nerve (usually the sciatic nerve), causing severe burning or stabbing pain down into the leg or foot (Fig. 45-1). The specific area of pain depends on the level of herniation. Painful muscle spasms of the affected leg also may occur.

Acute back pain usually results from injury or trauma. The patient typically hyperflexes or twists the back during a vehicular crash, or the injury occurs when the patient lifts a heavy object. Obesity places increased stress on the back muscles and can cause back pain. Smoking has been linked to disk degeneration, possibly caused by constriction of blood vessels that supply the spine. Congenital spinal conditions and scoliosis can also lead to back discomfort. Older adults are at high risk for both acute and chronic LBP. Petite, Euro-American women are at high risk for vertebral compression fractures from osteoporosis, which cause severe pain and decreased mobility. Chart 45-1 provides a list of specific factors that can cause low back pain in the older adult. Vertebral compression fractures are discussed in detail in Chapter 54.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) mandated that all industries develop and implement a plan to decrease musculoskeletal injuries among their workers. One way to meet this requirement is to develop an ergonomic plan for the workplace. Ergonomics is an applied science in which the workplace is designed to increase worker comfort (thus reducing injury) while increasing efficiency and productivity. An example is equipment design for office furniture that can help reduce back injuries. Chart 45-2 summarizes various ways to help prevent LBP.

Chart 45-2 Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Prevention of Low Back Pain and Injury

• Use proper body mechanics, with specific attention to bending, lifting, and sitting.

• Assess the need for assistance with your household chores or other activities.

• Participate in a regular exercise program, especially one that promotes back strengthening, such as swimming and walking.

• Do not wear high-heeled shoes.

• Use good posture when sitting, standing, and walking.

• Avoid prolonged sitting or standing. Use a footstool and ergonomic chairs and tables to lessen back strain. Be sure that equipment in the workplace is ergonomically designed to prevent injury.

• Keep weight within 10% of ideal body weight. Ensure adequate calcium intake.

• Stop smoking. If you are not able to stop, cut down on the number of cigarettes or decrease the use of other forms of tobacco.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Conduct a complete pain assessment as discussed in Chapter 5. Record the patient’s current pain score, as well as the worst and best score since the pain began. Ask if pain occurs or gets worse at night or during rest. Determine if a recent injury to the back has occurred. It is not unusual for the patient to say “I just turned around and felt my back go out.”

Diagnostic Assessment

Electro-diagnostic testing, such as electromyography (EMG) and nerve-conduction studies, may help distinguish motor neuron diseases from peripheral neuropathies and radiculopathies (spinal nerve root involvement). These tests are especially useful in chronic diseases of the spinal cord or associated nerves. Chapter 43 describes these tests in more detail.

Nonsurgical Management

Chronic Low Back Pain

Drug Alert

Some patients with back pain may have temporary relief from heat or cold application. Heat increases blood flow to the affected area and promotes the healing of injured nerves. Moist heat from heat packs or hot towels applied for 20 to 30 minutes at least four times per day is often recommended. Hot showers or baths may also be beneficial, although there is insufficient data to support the use of superficial heat/cold applications for low back pain (van Middelkoop et al., 2011).

The physical therapist also works with the patient to develop an individualized exercise program. The type of exercises prescribed depends on the location and nature of the injury and the type of pain. The patient does not begin exercises until acute pain is reduced by other means. Several specific exercises for LBP are listed in Chart 45-3. A systematic review of 37 studies showed that there is low quality evidence for the effectiveness of exercise for low back pain (van Middelkoop et al., 2011). Water therapy combined with exercise is helpful for some patients with chronic pain. The water also provides muscle resistance during exercise to prevent atrophy.

Chart 45-3 Patient and Family Education

Preparing For Self-Management: Typical Exercises for Chronic or Postoperative Low Back Pain

Extension Exercises

• Stomach lying: Lie face down with a pillow under your chest; lift legs straight up (alternate legs) (may not be tolerated).

• Upper trunk extension: Lie face down with your arms at your sides, and lift your head and neck.

• Prone push-ups: Lie face down on a mat and, keeping your body stiff, push up to extend your arms.

Flexion Exercises

• Pelvic tilt: Lying on your back with your knees bent, tighten your abdominal muscles to push your lower back against the mat.

• Semi–sit-ups: Lying on your back with your knees bent, raise your upper body at a 45-degree angle and hold this position for 5 to 10 seconds.

• Knee to chest: Lying on your back with your knees bent, tighten your abdominal muscles to push your lower back against the mat. Now bring one or both knees to your chest and hold this position for 5 to 10 seconds.

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Imagery, acupuncture, music therapy, and herbal medicines are examples of other possible pain relief therapies for acute and chronic pain. Rubinstein et al. (2010) conducted a systematic review of research on the effectiveness of complementary and alternative medicine for chronic back pain. They concluded that acupuncture and herbal therapies provide short-term pain relief but spinal manipulation was not as effective. Chapters 2 and 5 describe most of these modalities in detail.

Surgical Management

Preoperative Care

Preoperative care for the patient preparing for lumbar surgery is similar to that for any patient undergoing surgery (see Chapter 16). Teach the patient about postoperative expectations, including:

• Techniques to get into and out of bed

• Sensations, such as numbness and tingling, that may occur in the affected leg or in both legs

Postoperative Care

Postoperative care depends on the type of surgery that was performed. In the postanesthesia care unit (PACU), vital signs and level of consciousness are monitored frequently, the same as for any surgery. Best practices for PACU nursing care are discussed in Chapter 18.

Conventional Open Surgery

Early postoperative nursing care focuses on preventing and assessing complications that might occur in the first 24 to 48 hours (Chart 45-4). As for any patient undergoing surgery, take vital signs at least every 4 hours during the first 24 hours to assess for fever and for hypotension, which could indicate bleeding or severe pain. Perform a neurologic assessment every 4 hours. Of particular importance are movement, strength, and sensation in the extremities.

Chart 45-4 Best Practice For Patient Safety & Quality Care

Assessing and Managing the Patient with Major Complications of Lumbar Spinal Surgery

| COMPLICATION | ASSESSMENT/INTERVENTIONS |

|---|---|

| Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage | |

| Fluid volume deficit | |

| Acute urinary retention | |

| Paralytic ileus | |

| Fat embolism syndrome (FES) (more common in people with spinal fusion) | |

| Persistent or progressive lumbar radiculopathy (nerve root pain) | |

| Infection (e.g., wound, diskitis, hematoma) | Monitor the patient’s temperature carefully (a slight elevation is normal). Increased temperature elevation or a spike after the second postoperative day is possibly indicative of infection. Report increased pain or swelling at the wound site or in the legs. Give antibiotics as prescribed if infection is confirmed. |

Critical Rescue

Community-Based Care

Teaching for Self-Management

After surgery, in collaboration with the physical therapist, instruct the patient to:

The physical therapist reviews and demonstrates the principles of body mechanics and muscle-strengthening exercises. The patient is then asked to demonstrate these principles (Chart 45-5). Formal physical therapy usually begins about 2 weeks after surgery. Teach the patient the importance of keeping all appointments and following the prescribed exercise plan.

Chart 45-5 Patient and Family Education

preparing for self-management: Use of Proper Body Positioning to Prevent Back Injury After Surgery

• When lifting an object, keep your back straight and do not bend at the waist; lift with your large thigh muscles.

• Avoid lifting heavy objects, such as furniture.

• Push objects rather than pull them.

• Avoid prolonged sitting or standing. Use a footstool to lessen back strain.

• Sit in chairs with good support. Sleep on a firm mattress.

• Avoid shoulder stooping; maintain proper posture.

• Do not walk or stand in high-heeled shoes for prolonged periods (for women).

Critical Rescue

Drug Alert

Physiological Integrity

Cervical Neck Pain

Pathophysiology

Cervical neck pain most often results from a bulging or herniation of the nucleus pulposus (HNP) in an intervertebral disk. As seen in Fig. 45-1, the disk tends to herniate laterally where the annulus fibrosus is weakest and the posterior longitudinal ligament is thinned. The result is spinal nerve root compression with resulting motor and sensory manifestations, typically in the neck, upper back (over the shoulder), and down the affected arm. The disk between the fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae (C5-6) is affected most often.

• Plain x-rays (show general arthritis changes and bony alignment)

• Computerized tomography (CT) scan (shows spinal bones, nerves, disks, and ligaments)

• Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (provides images of the spinal tissue, bones, spinal cord, nerves, ligaments, musculature, and disks)

• Bone scan (shows bone changes by injecting radioactive tracers, which attach to areas of increased bone production or show increased vascularity associated with tumor or infection)

• Myelogram/post-myelogram CT (evaluates nerve root lesions and any other mass lesion or infection that is within or impinging on the thecal sac)

• Electromyography/nerve conduction studies (helps differentiate cervical radiculopathy, ulnar or radial neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, or other peripheral nerve problems)

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

If conservative treatment is ineffective, surgery may be required, most often using a conventional open surgical approach. A neurosurgeon usually performs this surgery because of the complexity of the nerves and other structures in that area of the spine. Depending on the cause and the location of the herniation, either an anterior or posterior approach is used. An anterior cervical diskectomy and fusion (ACDF) is commonly performed. The patient is fitted with a large neck brace before surgery. Routine preoperative and postoperative care is the same as described in Chapters 16 and 18.

Critical Rescue

Chart 45-6 summarizes best practices for postoperative care and discharge planning. Complications of ACDF can occur from the brace or the surgery itself. The initial brace is worn for 4 to 6 weeks, depending on the patient. When it is removed, a soft collar is worn for several more weeks, or longer if needed. Potential complications of the anterior surgical approach can be found in Chart 45-7.

Chart 45-6 Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

Care of the Patient After an Anterior Cervical Diskectomy and Fusion

Postoperative Interventions

• Assess airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) (first priority!).

• Check for bleeding and drainage at the incision site.

• Monitor vital signs and neurologic status frequently.

• Check for swallowing ability.

• Assess the patient’s ability to void (may be a problem secondary to opiates).

• Assist the patient with ambulation within a few hours of surgery, if he or she is able.

Postoperative Complications of Anterior Cervical Diskectomy and Fusion

• Hoarseness due to laryngeal injury; may be temporary or permanent

• Temporary dysphagia; may last few days to several months; usually not severe

• Esophageal, tracheal, or vertebral artery injury

• Injury to the spinal cord or nerve roots

• Dura mater tears with associated cerebrospinal fluid leaks

• Pseudoarthrosis caused by nonunion of fusion

Spinal Cord Injury

Pathophysiology

Mechanisms of Injury

When enough force is applied to the spinal cord, the resulting damage causes many neurologic deficits. Sources of force include direct injury to the vertebral column (fracture, dislocation, and subluxation [partial dislocation]) or penetrating trauma from violence (gunshot or knife wounds). Although in some cases the cord itself may remain intact, at other times the cord undergoes a destructive process caused by a contusion (bruise), compression, laceration, or transaction (severing of the cord, either complete or incomplete) (Nayduch, 2010).

Penetrating injuries to the cord may also occur.

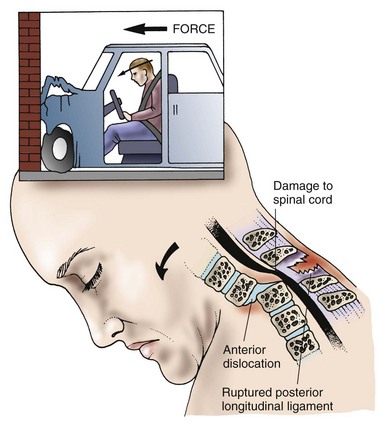

A hyperflexion injury occurs when the head is suddenly and forcefully accelerated (moved) forward, causing extreme flexion of the neck (Fig. 45-2). This type of injury often occurs in head-on vehicle collisions and diving accidents. Flexion injury to the lower thoracic and lumbar spine may occur when the trunk is suddenly flexed on itself, such as occurs in a fall on the buttocks. The posterior ligaments can be stretched or torn, or the vertebrae may fracture or dislocate. Either process may damage the spinal cord, causing hemorrhage, edema, and necrosis.

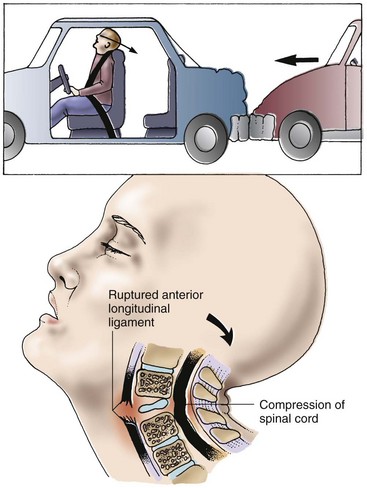

Hyperextension injuries occur most often in vehicle collisions in which the vehicle is struck from behind or during falls when the patient’s chin is struck (Fig. 45-3). The head is suddenly accelerated and then decelerated. This stretches or tears the anterior longitudinal ligament, fractures or subluxates the vertebrae, and perhaps ruptures an intervertebral disk. As with flexion injuries, the spinal cord may easily be damaged.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree