Cherie R. Rebar

Care of Patients with Oral Cavity Problems

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

10 Identify methods to help patients communicate effectively after oral surgery.

11 Plan care for patients who have disorders of the salivary glands.

12 State best practices for teaching or providing oral care for patients.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Keys for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Concept Map Creator

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

The oral cavity, or mouth, is where digestion of food begins. The teeth tear, grind, and crush food into small particles to promote swallowing. The enzymes in saliva begin the breakdown of carbohydrates. If a person cannot take food or fluid into the mouth, cannot chew food, or cannot swallow, the basic human need for nutrition may not be met by use of the GI tract. Adequate intake of fluids and nutrients into the body is vital to promote function of every body organ and system.

The pharynx (throat) is located just behind the mouth and has a role in both digestion and oxygenation. The pharynx is the portal between the mouth and the GI tract, where nutrients are broken down for utilization within the body. The pharynx also is a portal for oxygenation, as inhaled air passes through the nose, into the pharynx, and down into the trachea. A blockage of the posterior oral cavity, for example, by a tumor, can interfere with oxygenation and digestion.

Oral cavity disorders, then, can severely affect nutrition and oxygenation, as well as speech, body image, and self-esteem. Although there are many oral health problems, this chapter discusses the most common disorders. Nurses play an important role in maintaining and restoring oral health through nursing interventions, including patient and family education. Chart 56-1 lists ways to help maintain a healthy oral cavity.

Stomatitis

Pathophysiology

Stomatitis is a broad term that refers to inflammation within the oral cavity and may present in many different ways. Painful single or multiple ulcerations (called aphthous ulcers or “canker sores”) that appear as inflammation and erosion of the protective lining of the mouth are one of the most common forms of stomatitis. The sores cause pain, and open areas place the person at risk for bleeding and infection. Mild erythema (redness) may respond to topical treatments. Extensive stomatitis may require treatment with opioid analgesics. Stomatitis is classified according to the cause of the inflammation. Primary stomatitis, the most common type, includes aphthous (noninfectious) stomatitis, herpes simplex stomatitis, and traumatic ulcers. Secondary stomatitis generally results from infection by opportunistic viruses, fungi, or bacteria in patients who are immunocompromised. It can also result from drugs, such as chemotherapy. (See Chapter 24 for discussion of chemotherapy-induced stomatitis.)

A common type of secondary stomatitis is caused by Candida albicans. Candida is sometimes present in small amounts in the mouth, especially in older adults. Long-term antibiotic therapy destroys other normal flora and allows the Candida to overgrow. The result can be candidiasis, also called moniliasis, a fungal infection that is very painful. Candidiasis is also common in those undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, such as chemotherapy, radiation, and steroids.

In addition, the mouth is susceptible to the effects of human immune deficiency virus (HIV) infection. Other systemic diseases that can cause stomatitis include chronic kidney disease and inflammatory bowel disease. Poor oral health is a risk factor for certain infections, such as ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Stomatitis can result from infection, allergy, vitamin deficiency, systemic disease, and irritants such as tobacco and alcohol. Infectious agents, such as bacteria and viruses, may have a role in the development of recurrent stomatitis.

Certain foods may trigger allergic responses that cause aphthous ulcers. Foods such as coffee, potatoes, cheese, nuts, citrus fruits, and gluten may be causative factors. In some cases, strict diets have resulted in the improvement of ulcers. Deficiencies in complex B vitamins, folate, zinc, and iron associated with malnutrition can contribute to the formation of recurrent stomatitis.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

When performing an oral assessment, ask about a history of recent infections, nutritional changes, oral hygiene habits, oral trauma, or stress. A drug history should also be collected, including over-the-counter (OTC) drugs and nutritional and herbal supplements. Document the course of the current outbreak, and determine if stomatitis has occurred frequently. Ask the patient if the lesions interfere with swallowing, eating, or communicating.

The symptoms of stomatitis range in severity from a dry, painful mouth to open ulcerations, predisposing the patient to infection. These ulcerations can alter nutritional status because of difficulty with eating or swallowing. When they are severe, stomatitis and edema have the potential to obstruct the airway.

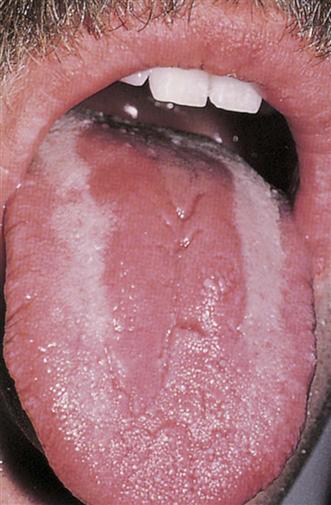

In oral candidiasis, a type of yeast infection, white plaque-like lesions appear on the tongue, palate, pharynx (throat), and buccal mucosa (inside the cheeks) (Fig. 56-1). When these patches are wiped away, the underlying surface is red and sore. Patients may report pain, but others describe the lesions as dry or hot. The older adult patient who has systemic illness or is taking antibiotics or chemotherapy is particularly susceptible to oral candidiasis.

While examining the mouth, wear nonsterile gloves. Use adequate lighting, using a penlight and tongue blade. Assess the mouth for lesions, coating, and cracking. Document characteristics of the lesions including their location, size, shape, odor, color, and drainage.

If lesions are seen along the pharynx and the patient reports dysphagia (pain on swallowing), suspect that the lesions might extend down the esophagus. Additional swallowing studies may be prescribed by the health care provider to establish a firm diagnosis.

The physical assessment should also include palpating the cervical and submandibular lymph nodes for swelling. Advanced practice nurses and other health care providers usually perform this part of the examination.

Interventions

Interventions for stomatitis are targeted toward health promotion through careful oral hygiene and food selection. When providing mouth care for the patient, the nurse may delegate oral care to unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP). Because the accountability for the delegated task is the nurse’s, remind UAP to use a soft-bristled toothbrush or disposable foam swabs to stimulate gums and clean the oral cavity. Toothpaste should be free of sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), if possible, because this ingredient has been associated with various types of stomatitis. Teach the patient to rinse the mouth every 2 to 3 hours with a sodium bicarbonate solution or warm saline solution (may be mixed with hydrogen peroxide). He or she should avoid most commercial mouthwashes because they have high alcohol content, causing a burning sensation in irritated or ulcerated areas. Health food stores sell more natural mouthwashes that are not alcohol-based. Teach the patient to check the labels for alcohol content. Frequent, gentle mouth care promotes débridement of ulcerated lesions and can prevent superinfections. Chart 56-2 lists measures for special oral care.

Drug therapy used for stomatitis includes antimicrobials, immune modulators, and symptomatic topical agents. Complementary and alternative therapies may also be tried.

Antimicrobials, including antibiotics, antivirals, and antifungals, may be necessary for control of infection. Tetracycline syrup (swish/swallow) 250 mg/10 mL four times daily for 10 days may be prescribed, especially for recurrent aphthous ulcers (RAUs). The patient rinses for 2 minutes and swallows the syrup, thus obtaining both topical and systemic therapy. Minocycline swish/swallow and chlorhexidine mouthwashes may also be used.

A regimen of IV acyclovir (Zovirax) is prescribed for immunocompromised patients who contract herpes simplex stomatitis. Acyclovir is typically administered to those with normal kidney function at a dose of 5 mg/kg, infused at a constant rate over a 1-hour period every 8 hours for 7 days. Patients with healthy immune systems may be given acyclovir in oral or topical form.

For fungal infections like yeast, nystatin (Mycostatin) oral suspension 600,000 units four times daily for 7 to 10 days is the drug most often used. The patient swishes and swallows the topical preparation. Ice pop troches (lozenges) of the antifungal preparation allow the drug to slowly dissolve, and the cold provides an analgesic effect. Topical triamcinolone in benzocaine (Kenalog in Orabase) and oral dexamethasone elixir used as a swish/expectorate preparation are commonly used for stomatitis, especially RAU.

Immune modulating agents that may be prescribed include:

The exact mechanism for how these drugs work is not clear. However, they may inhibit release of mediators that contribute to the inflammation seen in patients with RAU.

Other drugs can be used to control pain, such as OTC benzocaine anesthetics (e.g., Orabase, Anbesol) and camphor phenol (Campho-Phenique). Fifteen mL of 2% viscous lidocaine every 3 hours (maximum of 8 doses per day) can be used as a gargle or mouthwash. Teach patients to use this drug with extreme caution because its anesthetizing effect may cause burns from hot liquids in the mouth. Patients may also become more susceptible to choking when using viscous lidocaine.

Dietary changes may also help decrease pain. Cool or cold liquids can be very soothing. Teach patients to avoid hard, spicy, salty, and acidic foods or fluids that can further irritate the ulcers. Include foods high in protein and vitamin C to promote healing, including scrambled eggs, bananas, custards, puddings, and ice cream, unless the patient has lactose intolerance.

Oral Tumors

Oral cavity tumors can be benign, precancerous, or cancerous. Whether benign or malignant, tumors of the mouth affect many daily functions, including swallowing, chewing, and speaking. Pain accompanying the tumor can also limit daily activities and self-care. Oral tumors affect body image, especially if treatment involves removal of the tongue or part of the mandible (jaw) or requires a tracheostomy.

Premalignant Lesions

Leukoplakia

Leukoplakia presents as slowly developing changes in the oral mucous membranes causing thickened, white, firmly attached patches that cannot easily be scraped off. These patches appear slightly raised and sharply rounded. Most of these lesions are benign. However, a small percentage of them become cancerous. Although leukoplakia can be found anywhere on the oral mucosa, lesions on the lips or tongue are more likely to progress to cancer.

Leukoplakia results from mechanical factors that cause long-term oral mucous membrane irritation, such as poorly fitting dentures, chronic cheek nibbling, or broken or poorly repaired teeth. In addition, oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) can be found in patients with HIV infection. Tobacco products (smoked, dipped, or chewed) have also been implicated in the development of leukoplakia, sometimes referred to as “smoker’s patch.” Oral leukoplakia can be confused with oral candidal infection. However, unlike candidal infection, leukoplakia cannot be removed by scraping.

Leukoplakia is the most common oral lesion among adults. OHL is associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and can be an early manifestation of HIV infection. When associated with HIV infection, the appearance of OHL is highly correlated with progression from HIV infection to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Leukoplakia not associated with HIV infection is more often seen in people older than 40 years. Men have twice the incidence of leukoplakia that women have, but this ratio is changing because increasing numbers of women are smoking.

Erythroplakia

Erythroplakia presents as a red, velvety mucosal lesion on the surface of the oral mucosa. There are more malignant changes in erythroplakia than in leukoplakia; therefore erythroplakia is often considered “precancerous” in presentation. As such, these lesions should be regarded with suspicion and analyzed by biopsy. Erythroplakia is most commonly found on the floor of the mouth, tongue, palate, and mandibular mucosa. It can be difficult to distinguish from inflammatory or immune reactions.

Oral Cancer

In the past decade, dentists and physicians have begun systematically screening their patients for oral cancer. Oral assessment has become a part of the routine dental examination. People should visit a dentist at least twice a year for professional dental hygiene and oral cancer screening, which includes inspecting and palpating the mouth for lesions.

Prevention strategies for oral cancer include minimizing sun and tanning bed exposure, tobacco cessation, and decreasing alcohol intake. Most dentists now use digital technology instead of x-rays when performing the annual or biannual dental examination. Excessive, prolonged radiation from x-rays has been associated with head and neck cancer (Oral Cancer Foundation, 2010). Teach patients to follow the guidelines in Chart 56-1 to maintain oral health.

Pathophysiology

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

More than 90% of oral cancers are squamous cell carcinomas that begin on the surface of the epithelium. Over a period of many years, premalignant (or dysplastic) changes begin. Cells begin to vary in size and shape. Alterations in the thickness of the lining of the epithelium develop, resulting in atrophy. These tumors usually grow slowly, and the lesions may be large before the onset of symptoms unless ulceration is present. Mucosal erythroplasia is the earliest sign of oral carcinoma. Oral lesions that appear as red, raised, eroded areas are suspicious for cancer. A lesion that does not heal within 2 weeks or a lump or thickening in the cheek is a symptom that warrants further assessment (Oral Cancer Foundation, 2010).

Squamous cell cancer can be found on the lips, tongue, buccal mucosa, and oropharynx. The major risk factors in its development are increasing age, tobacco use, and alcohol use. Most oral cancers occur in people older than 40 years. Tobacco use in any form (e.g., smoking or chewing tobacco) can increase the risk for cancer. A person who frequently consumes alcohol and uses tobacco in any form is at the highest risk. Genetic changes in patients with oral cancer have been found, especially the mutation of the TP53 gene (McCance et al., 2010).

An increased rate of oral cancer is found in people with occupations such as textile workers, plumbers, and coal and metal workers. Additional factors, such as sun exposure, poor nutritional habits, poor oral hygiene, and infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV16) may also contribute to oral cancer (Oral Cancer Foundation, 2010). People with periodontal (gum) disease in which mandibular (jaw) bone loss has occurred are especially at risk for cancer of the mouth.

Mouth cancers account for about 3% of all cancers in men and 2% of all cancers in women in the United States. Over 37,000 new cases are diagnosed each year, with almost 8000 deaths (Oral Cancer Foundation, 2010). Most cancers occur in middle-aged and older people, although in recent years, younger adults have been affected, probably as a result of sun exposure.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma of the mouth occurs primarily on the lips. The lesion is asymptomatic and resembles a raised scab. With time, it evolves into a characteristic ulcer with a raised, pearly border. Basal cell carcinomas do not metastasize (spread) but can aggressively involve the skin of the face. The major risk factor for this type of cancer is excessive sunlight exposure.

Basal cell carcinoma occurs as a result of the failure of basal cells to mature into keratinocytes. It is the second most common type of oral cancer, but it is much less common than squamous cell carcinoma.

Kaposi’s Sarcoma

Kaposi’s sarcoma is a malignant lesion in blood vessels. It is usually painless and appears as a raised, purple nodule or plaque. In the mouth, the hard palate is the most common site of Kaposi’s sarcoma, but it can be found also on the gums, tongue, or tonsils. It is most often associated with AIDS. (See Chapter 21 for a complete discussion of Kaposi’s sarcoma.)

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Begin by assessing the patient’s routine oral hygiene regimen and use of dentures or oral appliances, which might add to discomfort or mechanically irritate the mucosa. Ask about oral bleeding, which might indicate an ulcerative lesion or periodontal (gum) disease. Determine the patient’s past and current appetite and nutritional state, including difficulty with chewing or swallowing. A continuing trend of weight loss may be related to metastasis, heavy alcohol intake, difficulty in eating or chewing, or an underlying health problem (Chart 56-3).