Chapter 63 Care of Patients with Malnutrition and Obesity

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Collaborate with members of the health care team when providing care for patients with malnutrition or obesity.

2. Protect bariatric patients from injury.

3. Select appropriate activities to delegate to unlicensed assistive personnel to promote a patient’s nutrition.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

4. Provide care that meets the special nutrition needs of older adults.

5. Teach overweight and obese patients the importance of lifestyle changes to promote health.

6. Perform a nutrition screening for all patients to determine if they are at high risk for nutritional health problems.

7. Identify the key recommendations from the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 document.

9. Interpret findings of a nutrition screening and assessment.

10. Calculate body mass index (BMI), and interpret findings.

11. Describe the risk factors for malnutrition, especially for older adults.

12. Explain why serum visceral protein levels indicate change in nutritional status.

13. Identify the role of nutritional supplements in restoring or maintaining nutrition.

14. Describe complications of total enteral nutrition (TEN).

15. Explain how to prevent complications of total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

16. Explain how to maintain enteral tube patency.

17. Describe evidence-based practices to prevent aspiration for patients with nasoenteric tubes.

18. Explain the medical complications associated with obesity.

19. Identify the role of drug therapy in the management of obesity.

20. Prioritize nursing care for patients having bariatric surgery.

21. Develop a discharge teaching plan for patients having bariatric surgery.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Nutrition Standards for Health Promotion and Maintenance

The role of nutrition in disease has been a subject of interest for many years. The current focus is on health promotion and the prevention of disease by healthy eating and exercise. In the United States, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans are revised by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) every 5 years. The most recent guidelines (2010) emphasize the need to include preferences of specific racial/ethnic groups, vegetarians, and other populations when selecting foods to maintain a healthful diet that is balanced with moderation and variety. If alcohol is consumed, it should be limited to one drink per day for women and two drinks for men (USDA, 2010). Examples of other guidelines are listed in Table 63-1.

TABLE 63-1 EXAMPLES OF 2010 DIETARY GUIDELINES FOR AMERICANS

Source: Dietary Guidelines for Americans Council. (2010). Retrieved March 31, 2011, from www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/DietaryGuidelines/2010/DGAC/Report/A-ExecSummary.pdf.

The USDA also recently designed a picture to remind people about the good foods to increase and the foods that should be reduced in the daily diet. Fig. 63-1 illustrates the USDA’s MyPlate to show that half of each meal should consist of fruits and vegetables. When grains are consumed, half of them should be whole grains rather than refined grain products.

An increasing number of people are adopting a variety of vegetarian diet patterns for health, environmental, or moral reasons. In general, vegetarians are leaner than those who consume meat. The lacto-vegetarian eats milk, cheese, and dairy foods but avoids meat, fish, poultry, and eggs. The lacto-ovo-vegetarian includes eggs in his or her diet. The vegan eats only foods of plant origin. Some people among these groups eat fish as well. Vegans can develop anemia as a result of vitamin B12 deficiency. Therefore they should include a daily source of vitamin B12 in their diets, such as a fortified breakfast cereal, fortified soy beverage, or meat substitute. All vegetarians should ensure that they get adequate amounts of calcium, iron, zinc, and vitamins D and B12. Well-planned vegetarian diets can provide adequate nutrition. The National Agriculture Library (2008) publishes a Vegetarian Nutrition Resource List that provides credible resources regarding vegetarian health.

Many people have specific food preferences based on their ethnicity or race. For example, for people of Hispanic descent, tortillas, beans, and rice may be desired over pasta, risotto, and potatoes. Never assume that a person’s racial or ethnic background means that he or she eats only foods associated with his or her primary ethnicity. Health teaching about nutrition should incorporate any cultural preferences (also see Chapter 4).

One of the most recent publications from Health Canada on nutrition is the Canada Food Guide. Compared with previous documents, it includes more culturally diverse foods, information on trans fats, customized individual recommendations, and exercise guidelines. Several booklets can be purchased to help people select the best foods and nutrients from the new Guide, such as Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide. In addition, Canada has published a separate booklet to address the special needs of some of its indigenous people. The Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide—First Nations, Inuit, and Métis includes berries, wild plants, and wild game to reflect the values and traditions for aboriginal people living in Canada (Health Canada, 2007).

Nutritional Assessment

Evaluation of nutritional status is an important part of total patient assessment and includes:

• Review of the nutritional history

• Food and fluid intake record

• Health history and physical assessment

Initial Nutritional Screening

The initial nutritional screening includes inspection, measured height and weight, weight history, usual eating habits, ability to chew and swallow, and any recent changes in appetite or food intake. Examples of questions that help identify patients at risk for nutritional problems are part of the history and physical assessment (Chart 63-1).

Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

Nutritional Screening Assessment

General

• Does the patient have any conditions that cause nutrient loss, such as malabsorption syndromes, draining abscesses, wounds, fistulas, or prolonged diarrhea?

• Does the patient have any conditions that increase the need for nutrients, such as fever, burn, injury, sepsis, or antineoplastic therapies?

• Has the patient been NPO for 3 days or more?

• Is the patient receiving a modified diet or a diet restricted in one or more nutrients?

• Is the patient being enterally or parenterally fed?

• Does the patient describe food allergies, lactose intolerance, or limited food preferences?

• Has the patient experienced a recent unexplained weight loss?

• Is the patient on drug therapy, either prescription, over-the-counter, or herbal/natural products?

Gastrointestinal

• Does the patient report nausea, indigestion, vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation?

• Does the patient exhibit glossitis (tongue inflammation), stomatitis (oral inflammation), or esophagitis?

• Does the patient have difficulty chewing or swallowing?

• Does the patient have a partial or total GI obstruction?

Modified with courtesy of Ross Products Division, Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, OH.

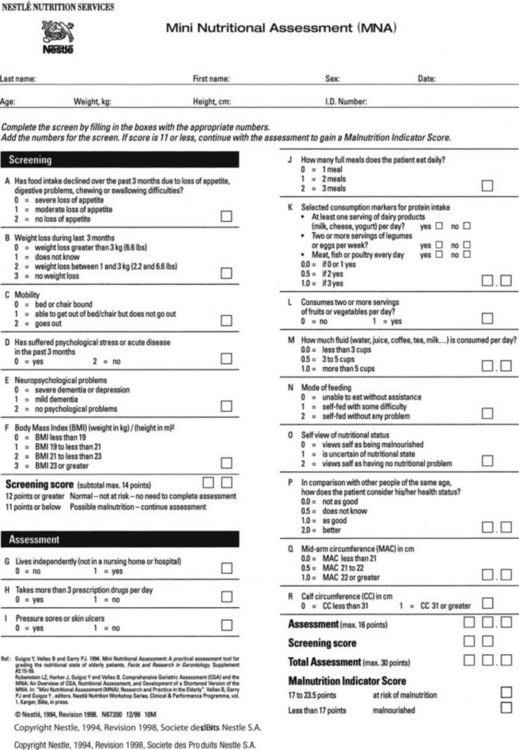

The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), a two-part tool that has been tested worldwide, provides a reliable, rapid assessment for patients in the community and in any health care setting. The first part (A-F) is a screening section that takes 3 minutes to complete and asks about food intake, mobility, and body mass index (BMI) (described on p. 1339). It also screens for weight loss, acute illness, and psychological health problems. If the patient scores 11 points or less, the second part (G-R) of the MNA is completed, for an additional 12 questions. The entire assessment takes less than 15 minutes (Fig. 63-2) (DiMaria-Ghalili & Guenter, 2008). A new MNA® Short Form can be used as a stand-alone tool to evaluate whether the older patient is well-nourished, at risk for malnutrition, or malnourished. The alternative is to take the patient’s calf circumference, which can be a reliable alternative if BMI is unavailable.

Anthropometric Measurements

Action Alert

Changes in body weight can be expressed by three different formulas:

1. Weight as a percentage of ideal body weight (IBW):

2. Current weight as a percentage of usual body weight (UBW):

BMI can also be determined using a table that is linked with height and weight. The least risk for malnutrition is associated with scores between 18.5 and 25. BMIs above and below these values are associated with increased health risks (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009).

Considerations for Older Adults

Body weight and BMI usually increase throughout adulthood until about 60 years of age. As people get older, they become less hungry and eat less, even if they are healthy. Older adults should have a BMI between 23 and 27 (DiMaria-Ghalili & Amella, 2005).

The average daily energy intake expended by this group tends to be more than the average energy intake. This physiologic change has been called the “anorexia of aging” (Conte et al., 2009). Many older adults are underweight, leading to undernutrition and increased risk for illness.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Malnutrition

Pathophysiology

Other common complications of severe malnutrition in adults include:

• Leanness and cachexia (muscle wasting with prolonged malnutrition)

• Decreased activity tolerance

• Dry, flaking skin and various types of dermatitis

• Infection, particularly postoperative infection and sepsis

Considerations for Older Adults

Older adults in the community or in any health care setting are most at risk for poor nutrition, especially PEM. Risk factors include physiologic changes of aging, environmental factors, and health problems. Chart 63-2 lists some of these major factors. Chapter 3 discusses nutrition for older adults in more detail.

Chart 63-2 Nursing Focus on the Older Adult

Risk Assessment for Malnutrition

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Assess for manifestations of various nutrient deficiencies (Table 63-2). Inspect the patient’s hair, eyes, oral cavity, nails, and musculoskeletal and neurologic systems. Examine the condition of the skin, including any reddened or open areas. The previously described anthropometric measurements may also be obtained. The nurse or UAP should monitor all food and fluid intake and note any mouth pain or difficulty in chewing or swallowing. A 3-day caloric intake may be collected and then calculated by the dietitian.

TABLE 63-2 MANIFESTATIONS OF NUTRIENT DEFICIENCIES

| Sign/Symptom | Potential Nutrient Deficiency |

|---|---|

| Hair | |

| Alopecia | Zinc |

| Easy to remove | Protein |

| Lackluster hair | Protein |

| “Corkscrew” hair | Vitamin C |

| Decreased pigmentation | Protein |

| Eyes | |

| Xerosis of conjunctiva | Vitamin A |

| Corneal vascularization | Riboflavin |

| Keratomalacia | Vitamin A |

| Bitot’s spots | Vitamin A |

| Gastrointestinal Tract | |

| Nausea, vomiting | Pyridoxine |

| Diarrhea | Zinc, niacin |

| Stomatitis | Pyridoxine, riboflavin, iron |

| Cheilosis | Pyridoxine, iron |

| Glossitis | Pyridoxine, zinc, niacin, folic acid, vitamin B12 |

| Magenta tongue | Vitamin A, riboflavin |

| Swollen, bleeding gums | Vitamin C |

| Fissured tongue | Niacin |

| Hepatomegaly | Protein |

| Skin | |

| Dry and scaling | Vitamin A |

| Petechiae/ecchymoses | Vitamin C |

| Follicular hyperkeratosis | Vitamin A |

| Nasolabial seborrhea | Niacin |

| Bilateral dermatitis | Niacin |

| Extremities | |

| Subcutaneous fat loss | Calories |

| Muscle wastage | Calories, protein |

| Edema | Protein |

| Osteomalacia, bone pain, rickets | Vitamin D |

| Hematologic | |

| Anemia | Vitamin B12, iron, folic acid, copper, vitamin E |

| Leukopenia, neutropenia | Copper |

| Low prothrombin time, prolonged clotting time | Vitamin K, manganese |

| Neurologic | |

| Disorientation | Niacin, thiamine |

| Confabulation | Thiamine |

| Neuropathy | Thiamine, pyridoxine, chromium |

| Paresthesia | Thiamine, pyridoxine, vitamin B12 |

| Cardiovascular | |

| Congestive heart failure, cardiomegaly, tachycardia | Thiamine |

| Cardiomyopathy | Selenium |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias | Magnesium |

Courtesy of Ross Products Division, Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, OH.

Psychosocial Assessment

The psychosocial history provides information about the patient’s economic status, occupation, educational level, gender orientation, ethnicity/race, living and cooking arrangements, and mental status. Determine whether financial resources are adequate for providing the necessary food. If resources are inadequate, the social worker or case manager may refer the patient and family to available community services. Chapter 3 discusses nutrition in older adults in more detail.

Laboratory Assessment

Serum albumin, thyroxine-binding prealbumin, and transferrin are measures of visceral proteins. Serum albumin is a plasma protein that reflects the nutritional status of the patient a few weeks before testing and is therefore not the most sensitive test. In addition, patients who are dehydrated often have high levels of albumin and those with fluid excess have a lowered value. The normal serum albumin level for men and women is 3.5 to 5.0 g/dL or 35 to 50 g/L (SI units) (Pagana & Pagana, 2010).

Thyroxine-binding prealbumin (PAB) is a plasma protein that provides a more sensitive indicator of nutritional deficiency because of its short half-life of 2 days. Depending on the laboratory test used, the normal PAB range is 15 to 36 mg/dL or 150 to 360 mg/L (SI units) (Pagana & Pagana, 2010). PAB can also assess improvement in nutritional status with refeeding; levels can increase by 1 mg/dL daily with adequate nutritional support.

Cholesterol levels normally range between 160 and 200 mg/dL in adult men and women. Values are typically low with malabsorption, liver disease, pernicious anemia, end-stage cancer, or sepsis. A cholesterol level below 160 mg/dL has been identified as a possible indicator of malnutrition. Cholesterol testing is discussed in more detail in Chapter 35.

Planning and Implementation

Improving Nutrition

Interventions

Nutrition Management

Action Alert

Considerations for Older Adults

Some patients, especially older adults, may take a long time to eat even small quantities of food because they tend to be less hungry than younger adults. If available, suggest that family members bring in favorite or ethnic foods that the patient might be more likely to eat. Teach them about ways to encourage the patient to increase food intake. Chart 63-3 describes additional interventions to promote nutritional intake in older adults.

Chart 63-3 Nursing Focus on the Older Adult

Promoting Nutritional Intake

• Be sure patient is toileted and receives mouth care before mealtime.

• Make sure that patient has glasses and hearing aids in place, if appropriate, during meals.

• Be sure that bedpans, urinals, and emesis basins are removed from sight.

• Give analgesics to control pain and/or antiemetics for nausea at least 1 hour before mealtime.

• Remind unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) to have patient sit in chair, if possible, at mealtime.

• If needed, open cartons and packages and cut up food at the patient’s and/or family’s request.

• Observe the patient during meals for food intake.

• Ask the patient about food likes and dislikes and ethnic food preferences.

• Encourage self-feeding, or feed the patient slowly; delegate this activity to UAP if desired.

• If feeding patient, sit at eye-level if culturally appropriate.

• Create an environment that is conducive to eating and socialization and relaxation, if possible.

• Decrease distractions, such as environmental noise from television, music, or other people.

• Provide adequate, nonglaring lighting.

• Keep patient away from offensive or medicinal odors.

• Keep eye contact with the patient during the meal if culturally appropriate.

• Serve snacks with activities, especially in long-term care settings; delegate this activity to UAP if desired.

• Document the percentage of food eaten at each meal and snack; delegate this activity to UAP if appropriate.

• Ensure that meals are visually appealing, appetizing, appropriately warm or cold, and properly prepared.

• Do not interrupt patients during mealtimes for nonurgent procedures or rounds.

• Assess for need for supplements between meals and at bedtime.

• Review the patient’s drug profile, and discuss with the health care provider the use of drugs that might be suppressing appetite.

• If the patient is depressed, be sure that the depression is treated by the health care provider.

Nutritional supplements used in acute care, long-term care, and home care can be costly. In addition, patients may refuse them and the supplements are then wasted. In a classic study, Bender et al. (2000) found that a more successful alternative to having the MNS given by nursing assistant staff in the nursing home was to have the supplements delivered by nurses during their usual medication passes. In this study, the nurses gave 60 mL or more of the MNS at least four times a day with the residents’ medications. As a result, the patients gained weight and had fewer pressure ulcers, thus making the program very cost-effective and providing positive clinical outcomes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree