Chapter 60 Care of Patients with Inflammatory Intestinal Disorders

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Describe the importance of collaborating with health care team members to provide care for patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Health Promotion and Maintenance

2. Differentiate care for older adults with acute and chronic inflammatory bowel disorders.

3. Develop a health teaching plan for patients to promote self-management when caring for ileostomy or other surgical diversion.

4. Identify community resources for patients and families regarding chronic IBD.

6. Identify expected body image changes associated with having an ileostomy or other surgical diversion.

8. Differentiate common types of acute inflammatory bowel disease.

9. Develop a collaborative plan of care for the patient who has appendicitis and peritonitis.

10. Discuss the common causes of gastroenteritis.

11. Compare and contrast the pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

12. Identify priority problems for patients with ulcerative colitis.

13. Explain the purpose of and nursing implications related to drug therapy for patients with IBD.

14. Plan priority postoperative care for a patient undergoing surgery for IBD.

15. Develop a hospital discharge teaching plan for patients having surgery for IBD.

16. Explain the role of nutrition therapy in managing the patient with diverticular disease.

17. Describe the comfort measures that the nurse can use for the patient with anal disorders.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Acute Inflammatory Bowel Disorders

Appendicitis

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

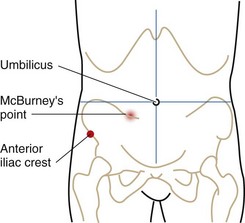

Perform a complete pain assessment. Initially, pain can present anywhere in the abdomen or flank area. As the inflammation and infection progress, the pain becomes more severe and steady and shifts to the RLQ between the anterior iliac crest and the umbilicus. This area is referred to as McBurney’s point (Fig. 60-1). Abdominal pain that increases with cough or movement and is relieved by bending the right hip or the knees suggests perforation and peritonitis. An advanced practice nurse or other health care provider assesses for muscle rigidity and guarding on palpation of the abdomen. The patient may report pain after release of pressure. This is referred to as “rebound” tenderness.

Surgical Management

Preoperative teaching is often limited because the patient is in pain or may be transferred quickly to the operating suite for emergency surgery. The patient is prepared for general anesthesia and surgery, as described in Chapter 16. After surgery, care of the patient who has undergone an appendectomy is the same as that required for anyone who has received general anesthesia (see Chapter 18).

Peritonitis

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Physical findings of peritonitis (Chart 60-1) depend on several factors: the stage of the disease, the ability of the body to localize the process by walling off the infection, and whether the inflammation has progressed to generalized peritonitis. The patient most often appears acutely ill, lying still, possibly with the knees flexed. Movement is guarded, and he or she may report and show signs of pain (e.g., facial grimacing) with coughing or movement of any type. During inspection, observe for progressive abdominal distention, often seen when the inflammation markedly reduces intestinal motility. Auscultate for bowel sounds, which usually disappear with progression of the inflammation.

Peritonitis

Action Alert

Surgical Management

The preoperative care is similar to that described in Chapter 16 for patients having general anesthesia. Chapter 18 describes general postoperative care for exploratory laparotomy. Multi-system complications can occur with peritonitis. Loss of fluids from the extracellular space to the peritoneal cavity, NGT suctioning, and NPO status require that the patient receives IV fluid replacement. Be sure that unlicensed assistive personnel (UAP) carefully measure intake and output. Fluid rates may be changed frequently based on laboratory values and patient condition.

Action Alert

Gastroenteritis

Pathophysiology

The following discussion of gastroenteritis includes the epidemic viral form and the bacterial forms (Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, and shigellosis) (Table 60-1). Organisms associated with food poisoning are discussed later in this chapter.

TABLE 60-1 COMMON TYPES OF GASTROENTERITIS AND THEIR CHARACTERISTICS

| TYPE | CHARACTERISTICS |

|---|---|

| Viral Gastroenteritis | |

| Epidemic viral | Caused by many parvovirus-type organisms |

| Transmitted by the fecal-oral route in food and water | |

| Incubation period 10-51 hrs | |

| Communicable during acute illness | |

| Rotavirus and Norwalk virus | Transmitted by the fecal-oral route and possibly the respiratory route |

| Incubation in 48 hrs | |

| Rotavirus is most common in infants and young children | |

| Norwalk virus affects young children and adults | |

| Bacterial Gastroenteritis | |

| Campylobacter enteritis | Transmitted by the fecal-oral route or by contact with infected animals or infants |

| Incubation period 1-10 days | |

| Communicable for 2-7 weeks | |

| Escherichia coli diarrhea | Transmitted by fecal contamination of food, water, or fomites |

| Shigellosis | Transmitted by direct and indirect fecal-oral routes |

| Incubation period 1-7 days | |

| Communicable during the acute illness to 4 wk after the illness | |

| Humans possibly carriers for months | |

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Action Alert

As part of the laboratory assessment, Gram stain of stool is usually done before culture. Cultures positive for the organism are diagnostic (Pagana & Pagana, 2010). Many WBCs on Gram stain suggest shigellosis. The presence of WBCs and RBCs in the stool may indicate Campylobacter gastroenteritis.

Teaching for Self-Management

During the acute phase of the illness, teach the patient and family about the importance of fluid replacement. Teaching the patient and family about reducing the risk for transmission of gastroenteritis is also important (Chart 60-2). Adhere to these precautions for up to 7 weeks after the illness or up to several months if Shigella was the offending organism.

Chart 60-2 Patient And Family Education

Preparing For Self-Management: Preventing Transmission of Gastroenteritis

Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease are the two most common inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) that affect adults. Comparisons and differences are listed in Table 60-2. Viral and bacterial dysenteries can cause symptoms similar to those of IBD, and other problems must be ruled out before a definitive diagnosis is made.

TABLE 60-2 DIFFERENTIAL FEATURES OF ULCERATIVE COLITIS AND CROHN’S DISEASE

| FEATURE | ULCERATIVE COLITIS | CROHN’S DISEASE |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Begins in the rectum and proceeds in a continuous manner toward the cecum | Most often in the terminal ileum, with patchy involvement through all layers of the bowel |

| Etiology | Unknown | Unknown |

| Peak incidence at age | 15-25 yr and 55-65 yr | 15-40 yr |

| Number of stools | 10-20 liquid, bloody stools per day | 5-6 soft, loose stools per day, non-bloody |

| Complications | Hemorrhage Nutritional deficiencies | Fistulas (common) Nutritional deficiencies |

| Need for surgery | Infrequent | Frequent |

Ulcerative Colitis

Pathophysiology

Ulcerative colitis (UC) creates widespread inflammation of mainly the rectum and rectosigmoid colon but can extend to the entire colon when the disease is extensive. Distribution of the disease can remain constant for years. UC is a disease that is associated with periodic remissions and exacerbations (flare-ups) (McCance et al., 2010). Many factors can cause exacerbations, including intestinal infections.

The intestinal mucosa becomes hyperemic (has increased blood flow), edematous, and reddened. In more severe inflammation, the lining can bleed and small erosions, or ulcers, occur. Abscesses can form in these ulcerative areas and result in tissue necrosis (cell death). Continued edema and mucosal thickening can lead to a narrowed colon and possibly a partial bowel obstruction. Table 60-3 lists the categories of the severity of UC.

TABLE 60-3 AMERICAN COLLEGE OF GASTROENTEROLOGISTS CLASSIFICATION OF UC SEVERITY

| SEVERITY | STOOL FREQUENCY | SIGNS/SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | <4 stools/day with/without blood | Asymptomatic |

| Laboratory values usually normal | ||

| Moderate | >4 stools/day with/without blood | Minimal symptoms |

| Mild abdominal pain | ||

| Mild intermittent nausea | ||

| Possible increased C-reactive protein* or ESR† | ||

| Severe | >6 bloody stools/day | Fever |

| Tachycardia | ||

| Anemia | ||

| Abdominal pain | ||

| Elevated C-reactive protein* and/or ESR† | ||

| Fulminant | >10 bloody stools/day | Increasing symptoms |

| Anemia may require transfusion | ||

| Colonic distention on x-ray |

UC, Ulcerative colitis.

* C-reactive protein is a sensitive acute-phase serum marker that is evident in the first 6 hours of an inflammatory process.

† ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) may be helpful but is less sensitive than C-reactive protein.

Adapted from Present, D.H. (2006). Current and investigational approaches in the management of ulcerative colitis. Secaucus, NJ: Thomson Professional Postgraduate Services/Shire Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

The patient’s stool typically contains blood and mucus. Patients report tenesmus (an unpleasant and urgent sensation to defecate) and lower abdominal colicky pain relieved with defecation. Malaise, anorexia, anemia, dehydration, fever, and weight loss are common. Extraintestinal manifestations such as migratory polyarthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and erythema nodosum are present in a large number of patients. The common complications of UC, including extraintestinal manifestations, are listed in Table 60-4.

TABLE 60-4 COMPLICATIONS OF ULCERATIVE COLITIS AND CROHN’S DISEASE

| COMPLICATION | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Hemorrhage/perforation | Lower gastrointestinal bleeding results from erosion of the bowel wall. |

| Abscess formation | Localized pockets of infection develop in the ulcerated bowel lining. |

| Toxic megacolon | Paralysis of the colon causes dilation and subsequent colonic ileus, possibly perforation. |

| Malabsorption | Essential nutrients cannot be absorbed through the diseased intestinal wall, causing anemia and malnutrition (most common in Crohn’s disease). |

| Nonmechanical bowel obstruction | Obstruction results from toxic megacolon or cancer. |

| Fistulas | In Crohn’s disease in which the inflammation is transmural, fistulas can occur anywhere but usually track between the bowel and bladder resulting in pyuria and fecaluria. |

| Colorectal cancer | Patients with ulcerative colitis with a history longer than 10 years have a high risk for colorectal cancer. This complication accounts for about one third of all deaths related to ulcerative colitis. |

| Extraintestinal complications | Complications include arthritis, hepatic and biliary disease (especially cholelithiasis), oral and skin lesions, and ocular disorders, such as iritis. The cause is unknown. |

| Osteoporosis | Osteoporosis occurs especially in patients with Crohn’s disease. |

Etiology and Genetic Risk

The exact cause of UC is unknown, but genetic and immunologic factors have been suspected. A genetic basis of the disease has been supported because it is often found in families and twins. Immunologic causes, including autoimmune dysfunction, are likely the etiology of extraintestinal manifestations of the disease. Epithelial antibodies in the IgG class have been identified in the blood of some patients with UC (McCance et al., 2010).

With long-term disease, cellular changes can occur that increase the risk for colon cancer. Damage from proinflammatory cytokines, such as specific interleukins (e.g., IL-1, IL-6, IL-8) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha, have cytotoxic effects on the colonic mucosa (McCance et al., 2010).

Incidence/Prevalence

Chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affects about 1.4 million people in the United States and is split about equally between ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (discussed later). Peak age for being diagnosed with UC is between 30 and 40 years and again at 55 to 65 years. Women are more often affected than men in their younger years, but men have the disease more often as middle-aged and older adults (Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, 2008).

Ulcerative colitis is more common among Jewish persons than among those who are not Jewish, and among whites more than non-whites (Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America, 2008). The reasons for these cultural differences are not known.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Laboratory Assessment

As a result of chronic blood loss, hematocrit and hemoglobin levels may be low, which indicates anemia and a chronic disease state. An increased WBC count, C-reactive protein, or erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is consistent with inflammatory disease. Blood levels of sodium, potassium, and chloride may be low as a result of frequent diarrheal stools and malabsorption through the diseased bowel (Pagana & Pagana, 2010). Hypoalbuminemia (decreased serum albumin) is found in patients with extensive disease from losing protein in the stool.

Analysis

The priority problems for patients with ulcerative colitis are:

1. Diarrhea and incontinence related to inflammation of the bowel mucosa

2. Pain related to inflammation and ulceration of the bowel mucosa and skin irritation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree