Care of Patients with Disorders of the Gallbladder, Liver, and Pancreas

Objectives

1. Explain the plan of care for the patient with cholelithiasis.

2. Describe treatment for the patient with cholecystitis.

3. List the ways in which the various types of hepatitis can be transmitted.

4. Identify signs and symptoms of the various types of hepatitis.

5. Devise appropriate nursing interventions for the patient with cirrhosis and ascites.

6. Indicate potential causes of liver failure.

7. Differentiate the signs and symptoms of acute and chronic liver failure.

8. Discuss the ethical issues associated with liver transplantation.

9. Devise a nursing care plan for the patient with cancer of the liver.

10. Prepare a plan for adequate pain control for the patient with pancreatitis.

11. Compare the treatment options for cancer of the pancreas.

Key Terms

ascites (ă-SĪ-tēz, p. 701)

asterixis (ăs-těr-ĬK-sĭs, p. 707)

biliary colic (BĬL-ē-ăr-ē kō-LĬC, p. 691)

caput medusa (KĂP-ět mě-DŪ-să, p. 701)

cholecystectomy (kō-lě-sĭs-TĚK-tō-mē, p. 692)

cholecystitis (kō-lě-sĭs-TĪ-tĭs, p. 691)

choledocholithiasis (kō-lěd-ō-kō-lĭ-THĪ-ă-sĭs, p. 690)

cholelithiasis (kō-lě-lĭ-THĪ-ă-sĭs, p. 690)

cirrhosis (sĭr-RŌ-sĭs, p. 701)

encephalopathy (ěn-sěf-ă-LŎP-ă-thē, p. 698)

esophageal varices (ě-sŏf-ă-JĒ-ăl VĂR-ĭ-sēz, p. 704)

fetor hepaticus (hě-PĂ-tĭ-kŭs, p. 707)

hematemesis (hē-mă-TĚM-ě-sĭs, p. 704)

hepatitis (hě-pă-TĪ-tĭs, p. 694)

icterus (ĬK-těr-ŭs, p. 702)

jaundice (JĂWN-dĭs, p. 691)

palmar erythema (ěr-ĭ-THĒ-mă, p. 701)

paracentesis (păr-ă-sěn-TĒ-sĭs, p. 702)

prodromal stage (prō-DRŌ-măl, p. 699)

pruritus (prū-RĪ-tŭs, p. 701)

pseudocyst (sū-dō-sĭst, p. 709)

spider angiomas (SPĪ-děr ăn-jē-Ō-măz, p. 701)

varices (VĂR-ĭ-sēz, p. xxx)

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

http://evolve.elsevier.com/deWit/medsurg

Disorders of the gallbladder

Cholelithiasis and Cholecystitis

Etiology

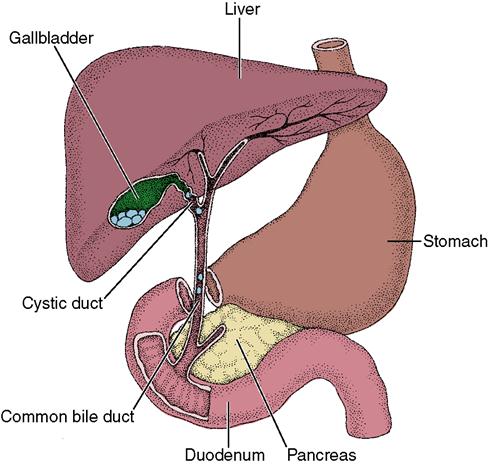

Cholelithiasis is the presence of gallstones within the gallbladder or in the biliary tract. The stones may vary in size, from very small “gravel” to stones as large as golf balls. Tiny stones pass into the bile ducts, where they become lodged and obstruct bile flow (Figure 31-1). When stones lodge in the common bile duct, the patient has choledocholithiasis. Cholelithiasis is more likely to occur in people with a sedentary lifestyle, a familial tendency, diabetes mellitus, and obesity. Cholesterol-lowering drugs increase the amount of cholesterol secreted in bile. This cholesterol secretion can increase the risk of gallstones.

Hemolytic disease, extensive resection of the bowel to treat Crohn’s disease, bariatric surgery, or rapid weight loss, multiple pregnancies and use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy also increase the risk for gallstones.

Cholecystitis is an inflammation of the gallbladder and is associated with gallstones in 90% to 95% of occurrences. Other causes include obstructive tumors of the biliary tract and severely stressful situations such as cardiac surgery, severe burns, or multiple trauma.

Pathophysiology

Cholelithiasis (gallstones) develops when the balance between cholesterol, bile salts, and calcium in the bile is altered to the point that these substances precipitate. When cholesterol precipitates, the nucleus of a stone can be formed. The stone grows as layers of cholesterol, calcium, or pigment accumulate over the nucleus. Immobility, pregnancy, and obstructive lesions decrease bile flow. Stasis of bile leads to changes in chemical composition and stone formation. The formation of stones within the gallbladder can cause irritation and areas of inflammation in the gallbladder wall (cholecystitis). Infection can occur from organisms such as Escherichia coli. The organisms enter the gallbladder through the sphincter of Oddi from adjacent structures.

Signs and Symptoms

Symptoms depend on the degree of obstruction to bile flow and extent of inflammation of the gallbladder. The absence of bile in the intestine results in clay-colored stools that float as a result of undigested fat content. If a duct is obstructed by a stone, obstruction of bile flow by stones in the cystic or common bile duct causes strong muscle contractions that attempt to move the stones along; severe pain may be triggered by a fatty meal. Nausea and vomiting, fever, and leukocytosis occur with cholecystitis. Pain may be referred to the right clavicle, scapula, or shoulder. As bile backs up into the liver and blood, jaundice (yellow tint to skin and sclera) occurs. If obstruction is unrelieved, inflammation occurs, and can progress to liver damage.

The symptom most often present in an acute flare-up of chronic cholecystitis is unbearable upper right quadrant pain (biliary colic). The pain sometimes is referred to the back at the level of the shoulder blades. Attacks can occur as frequently as daily or may not appear but once every year or so. Vomiting may accompany acute flare-ups, along with chills and fever. If the inflammation is not corrected or if there is an infection, the gallbladder can become filled with pus and rupture. Rupture spills gallbladder contents into the abdominal cavity and causes peritonitis.

Chronic cholecystitis causes milder symptoms between acute attacks. Symptoms are indigestion after eating fatty foods, flatulence, nausea after eating, and some discomfort in the right upper quadrant. Table 31-1 compares signs and symptoms of gallbladder disorders.

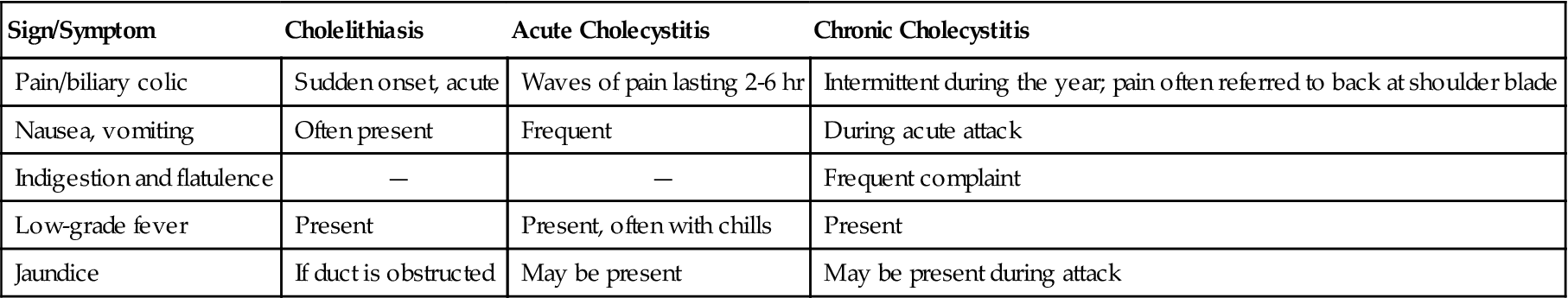

Table 31-1

Comparison of Gallbladder Disorders

| Sign/Symptom | Cholelithiasis | Acute Cholecystitis | Chronic Cholecystitis |

| Pain/biliary colic | Sudden onset, acute | Waves of pain lasting 2-6 hr | Intermittent during the year; pain often referred to back at shoulder blade |

| Nausea, vomiting | Often present | Frequent | During acute attack |

| Indigestion and flatulence | — | — | Frequent complaint |

| Low-grade fever | Present | Present, often with chills | Present |

| Jaundice | If duct is obstructed | May be present | May be present during attack |

Diagnosis

Gallstones usually can be diagnosed with ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT) of the gallbladder and biliary tract. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may be done to detect common duct stones. Cholescintigraphy (hepatoiminodiacetic acid [HIDA] scan) diagnoses abnormal contraction of the gallbladder or obstruction. Liver function tests are helpful to diagnose gallbladder and biliary tract disease. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) will be slightly elevated. If there is common duct obstruction, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase is elevated. In biliary obstruction, both direct bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels are elevated.

The diagnosis of cholecystitis is aided by indicators of infection, such as elevated white blood cell count and sedimentation rate.

Treatment

First, a low-fat diet, loss of excessive body weight, and restriction of alcohol intake are recommended and meals are spaced so that no large amounts of food are put into the intestinal tract at any one time. This avoids overstimulation of gallbladder activity. If the patient does not respond to this therapy or if bile obstruction occurs, correction of the obstructed biliary tract is indicated. Antibiotics are usually only given if peritonitis is present. Fluids are administered and electrolytes are rebalanced.

If stones may be in the common bile duct, it is explored either before or during surgery. Sometimes small stones may be removed during ERCP, in which the common duct can be visualized. The surgical procedure of choice is cholecystectomy (gallbladder removal). Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the most common surgical procedure used. Four small incisions are made in the abdomen; abdominal muscles are not cut, and the patient experiences less pain and a quicker recovery than with an “open” cholecystectomy. A laparoscope with an attached camera and a dissecting laser are used along with grasping forceps. Carbon dioxide (CO2) is instilled into the abdominal cavity to aid visualization. The gallbladder is removed through the incision at the umbilicus. The patient will have dressings over the four small incisions on the abdomen. There is essentially no difference in complications or outcomes for either open cholecystectomy or the laparoscopic procedure. Recovery time is shorter for the laparoscopic procedure (Thomas, 2009).

The nurse should monitor the laparoscopic patient closely for internal bleeding and watch for signs of increasing abdominal rigidity and pain, and for changes in vital signs. Sometimes the retained CO2 used during a laparoscopic procedure causes “free air” pain. Early and frequent ambulation helps the CO2 gas dissipate. The patient is discharged after recovering from the anesthesia, or 1 day postoperatively, depending on his age and condition, and must have careful discharge teaching about signs of complications.

With an open abdominal cholecystectomy, a 2- to 4-day stay in the hospital is usual and there is about a 6-week recovery period. Residual stones can lodge in the common duct after cholecystectomy. ERCP is usually used to remove residual stones.

Oral dissolution therapy is available and works best on small cholesterol stones. Ursodiol (Actigall) and chenodiol (Chenix) are prescribed for 6 months to 2 years to dissolve stones.

An experimental procedure called contact dissolution therapy involves injecting a drug, methyl tert-butyl ether, into the gallbladder to dissolve stones in 1 to 3 days. It can cause irritation and complications. It is being tested on patients with small stones (National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse, 2007).

Lithotripsy, or “shock wave” therapy, is occasionally used for gallstones. The procedure involves using sound waves directed through the body to break up the stones. The procedure takes 1 to 1½ hours, and the debris is then carried by the bile into the intestine. To be a candidate for this procedure, there must be no more than three cholesterol gallstones, each smaller than 1½ inches, and the patient must not be obese.

Nursing Management

Preoperative Care

Preoperatively, the gallstone patient may have a nasogastric tube to relieve nausea and vomiting. An analgesic may be ordered to decrease pain, and antiemetics are given for nausea.

Intravenous (IV) fluids are begun to prevent dehydration. Coagulation times are monitored if jaundice is present, and vitamin K, if needed, is administered before surgery to improve clotting ability of the blood. The patient scheduled for gallstone surgery has needs similar to those of any patient having abdominal surgery. Teaching is adapted for the standard procedure or the laparoscopic procedure (see Chapters 4 and 5).

Postoperative Care

The patient is placed in the semi-Fowler’s position after he recovers from anesthesia. This position is more comfortable and decreases strain on the sutures. The patient will also be able to take deep breaths and cough more easily in this position.

A patient who has had “open” gallbladder surgery needs proper care of the drains or tubes that may be in place after the surgery. In many cases, the surgery was performed to relieve an obstruction to the flow of bile through the bile ducts or to drain purulent material to the outside. The drainage is absorbed by the dressings over the surgical wound. Dressings must be changed often and should be checked frequently for signs of fresh bleeding. The drain is left in as long as necessary and is then removed by the surgeon.

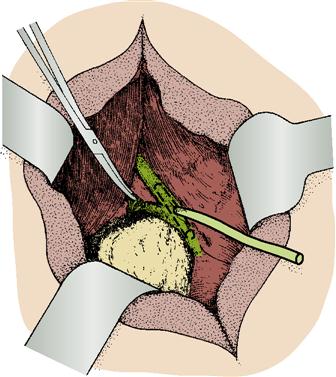

When an obstruction of the common bile duct has occurred because of stones or tumors, the surgeon may insert a small T-shaped tube (T-tube) directly into the common bile duct during an “open” cholecystectomy (Figure 31-2). This tube must be kept open at all times and is connected to a bedside drainage bag. The length of time the T-tube is left in place varies according to the condition of the patient. Only a small amount of bile will be going to the duodenum. No tension should be put on tubes or drains that have been inserted in the surgical wound. Dressings must be changed carefully because T-tubes are sutured in place, and if they are accidentally pulled out, the patient must be returned to the operating room and the incision reopened to replace the tube.

Montgomery straps are best for holding the dressings in place. The patient should be prepared to expect a greenish yellow discharge (bile) on the dressings. The drainage bag is emptied when the dressing is changed. The patient often goes home with the T-tube in place.

The nurse must carefully observe the color of the patient’s stools because a return of the normal brown colored stool is an indication that bile is flowing and entering the small intestine. If the bile duct is obstructed, there will be signs of jaundice and stool will be light in color.

The “open” cholecystectomy patient is reluctant to deep-breathe and cough because of pain in the operative area. Encourage these exercises, and auscultate lung sounds every shift to discover any signs of extra secretions or atelectasis. A patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump will help the patient to cooperate with turning, coughing, and ambulating and thus prevent complications.

No specific diet is recommended for the patient who has had surgery of the gallbladder, although it is wise to avoid excessive amounts of fatty foods.

Complications

Constant irritation of the gallbladder may contribute to cancer of the gallbladder. Inflammation and infection produce purulent material and a fistula may form. Necrosis, gangrene, and rupture of the gallbladder causing peritonitis may occur. Choledocholithiasis may cause inflammation of the common duct and obstruct the pancreatic duct. This can lead to pancreatitis.

Disorders of the liver

The liver becomes inflamed when injured by trauma, toxins, or tumor invasion. Disruption of the normal functions of the liver occurs depending on how much of the liver tissue is affected. Chronic inflammation causes fibrosis of the liver cells and abnormal function.

Hepatitis

Etiology and Pathophysiology

There are five types of viral hepatitis (Table 31-2) that cause physical problems. A sixth hepatitis virus, hepatitis G, does not seem to cause the symptoms of hepatitis. Liver cells are damaged either by direct action of the virus on hepatocytes or by cell-mediated immune responses to the virus. Hepatitis viruses cause extensive inflammation of the liver tissue. Liver cell damage results in necrosis of hepatic cells. The Kupffer cells proliferate and enlarge. Bile flow may be interrupted because of the inflammation. With severe inflammation, fibrous scar tissue may form in the liver. Scar tissue often obstructs normal blood and bile flow, causing further damage from ischemia.

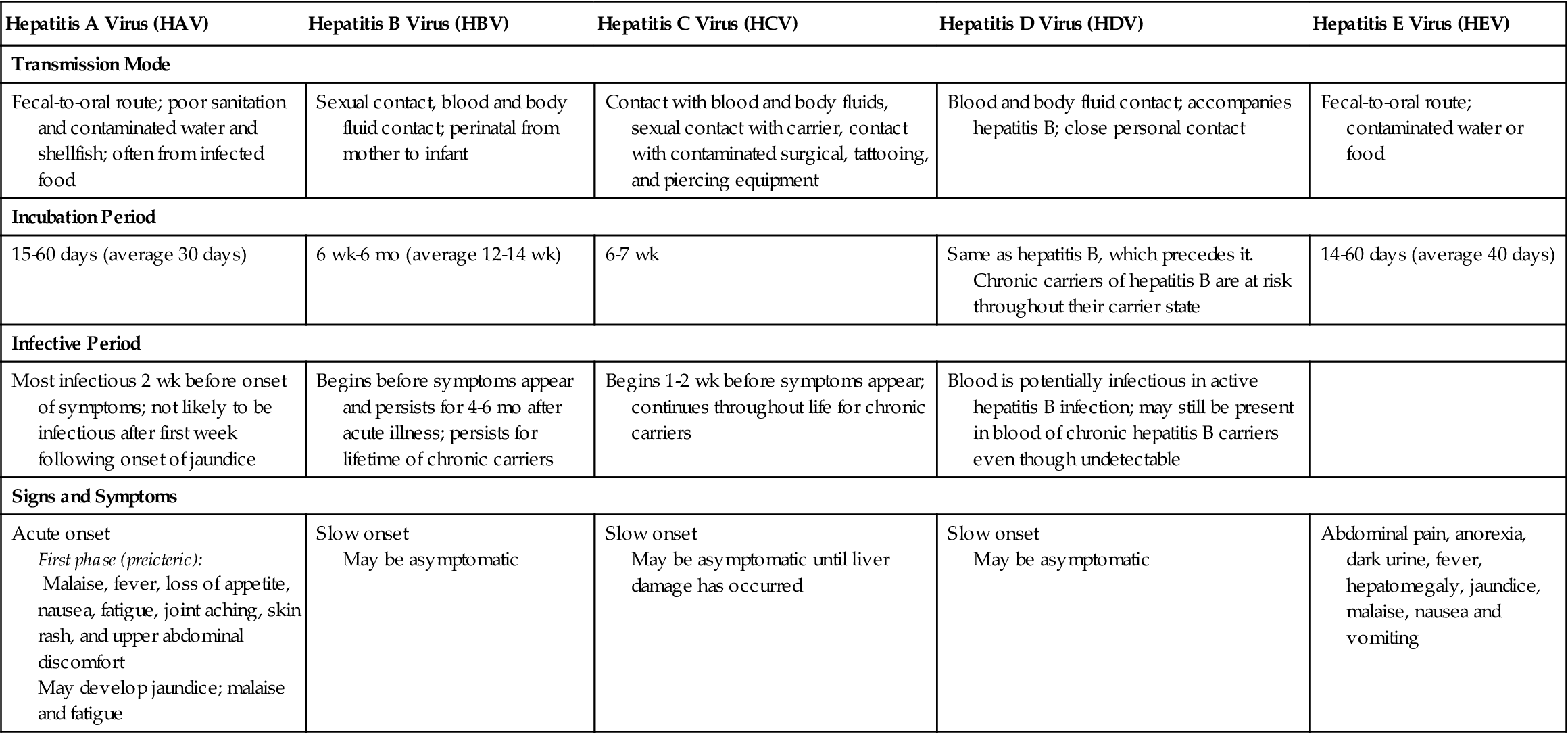

Table 31-2

Comparison of Hepatitis-Causing Viruses

| Hepatitis A Virus (HAV) | Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) | Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) | Hepatitis D Virus (HDV) | Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) |

| Transmission Mode | ||||

| Fecal-to-oral route; poor sanitation and contaminated water and shellfish; often from infected food | Sexual contact, blood and body fluid contact; perinatal from mother to infant | Contact with blood and body fluids, sexual contact with carrier, contact with contaminated surgical, tattooing, and piercing equipment | Blood and body fluid contact; accompanies hepatitis B; close personal contact | Fecal-to-oral route; contaminated water or food |

| Incubation Period | ||||

| 15-60 days (average 30 days) | 6 wk-6 mo (average 12-14 wk) | 6-7 wk | Same as hepatitis B, which precedes it. Chronic carriers of hepatitis B are at risk throughout their carrier state | 14-60 days (average 40 days) |

| Infective Period | ||||

| Most infectious 2 wk before onset of symptoms; not likely to be infectious after first week following onset of jaundice | Begins before symptoms appear and persists for 4-6 mo after acute illness; persists for lifetime of chronic carriers | Begins 1-2 wk before symptoms appear; continues throughout life for chronic carriers | Blood is potentially infectious in active hepatitis B infection; may still be present in blood of chronic hepatitis B carriers even though undetectable | |

| Signs and Symptoms | ||||

| Acute onset First phase (preicteric): Malaise, fever, loss of appetite, nausea, fatigue, joint aching, skin rash, and upper abdominal discomfort May develop jaundice; malaise and fatigue | Slow onset May be asymptomatic | Slow onset May be asymptomatic until liver damage has occurred | Slow onset May be asymptomatic | Abdominal pain, anorexia, dark urine, fever, hepatomegaly, jaundice, malaise, nausea and vomiting |

Liver cells do have the capacity to regenerate and resume their normal appearance. The cells can function as long as there are no complications.

Hepatitis A and hepatitis E viruses are transmitted primarily by the oral-fecal route. They are responsible for the epidemic forms of viral hepatitis. Hepatitis A virus can be transmitted by food handlers to customers or by mollusk shellfish from contaminated waters. Hepatitis E virus infection is primarily seen in less developed countries. It is transmitted through fecal contamination of water.

Hepatitis B, C, and D viruses may cause chronic inflammation and necrosis of the tissue. A carrier state of hepatitis B, C, or D may occur and asymptomatic individuals can transmit infection to others. Hepatitis B and C viruses are transmitted by parenteral routes and sexually as they are present in semen, vaginal secretions, and saliva of carriers. Sexual partners of patients who are carriers of hepatitis B or C virus are at high risk for contracting the virus. Hepatitis D virus coexists with hepatitis B or C virus, and is transmitted in the same ways.

Hepatitis C virus has been the main cause of post-transfusion hepatitis because before 1992 donor blood could not be screened for this type of hepatitis. The number of transfusion-related cases was reduced after screening was implemented. Intravenous drug use is currently a major cause of hepatitis C infection; therefore users are a target group for screening and counseling. The virus can also be transmitted by straws used to snort cocaine. Hepatitis B and C viruses can be transmitted from mother to infant. Both can occur in hemodialysis patients. Hepatitis B and C are the most serious forms of hepatitis, often progressing to chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death.

Signs and Symptoms

The clinical signs and symptoms of hepatitis A tend to have an acute onset, whereas in hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and hepatitis D the onset is slower and more insidious. There are three phases of hepatitis A. The first, the preicteric phase, precedes jaundice and lasts 1 to 21 days. When symptoms do occur, they may be vague and nonspecific manifestations (see Table 31-2.) The patient might think he has a mild case of influenza because the symptoms are so similar.

The icteric phase, characterized by jaundice, lasts 2 to 4 weeks. Urine becomes dark and stools may become light if bile flow is obstructed. Pruritus may occur from the bile pigment deposited in the skin. The liver becomes tender and enlarged.

The posticteric phase begins when jaundice is disappearing. Convalescence may take 2 to 4 months. Major complaints are malaise and fatigue. Liver enlargement may continue, but if the spleen was enlarged, it returns to normal in this phase.

For chronic hepatitis B and C, patients are likely to be asymptomatic or have symptoms of chronic liver disease. Acute hepatitis B and C patients could also be asymptomatic. Symptoms include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, poor appetite, right upper quadrant pain, dark urine, and light-colored stools.

Hepatitis D sometimes causes massive destruction of liver cells, liver failure, and death. Hepatitis B and D become chronic in 2% to 10% of infected patients. The patient is then a constant carrier of the virus. There are no currently known signs and symptoms of hepatitis G.

Diagnosis

Hepatitis is diagnosed by history, physical examination, and laboratory testing. Serologic assays or enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) detect specific antibodies to the various types of hepatitis. Molecular assays can detect viral nucleic acid. These assays do not measure the severity of disease or indicate prognosis. The genotype assay can be used to predict the response to and duration of therapy. Chronic hepatitis is determined by liver biopsy. Elevations in liver function tests (LFTs) are expected findings (Table 31-3). Abnormalities in the white blood cell count, platelets, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and prothrombin time may also occur depending on the severity of the disease.

Table 31-3

Laboratory Test Findings in Acute Viral Hepatitis

| Test | Abnormal Findings |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | Elevated in preicteric phase up to 20 times normal; decreases as jaundice subsides |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | Elevated in preicteric phase; ALT/AST ratio is greater than 1; decreases as jaundice subsides. |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) | Elevated |

| Bilirubin | Elevated unconjugated (direct) bilirubin |

| Alkaline phosphatase | Some elevation |

| Serum albumin | Normal or decreased |

| Serum bilirubin (total) | Elevated to about 8-15 mg/dL (137-257 µmol/L) |

| Prothrombin time | Prolonged |

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for acute viral hepatitis. Hepatitis A is treated by rest and avoidance of any substances, including alcohol, which can cause liver damage. These measures help the liver to regenerate. A well-balanced diet helps liver cells to heal. Four to six small meals a day are tolerated more readily than three larger ones. Sucking on hard candy is recommended and adds to caloric intake. Nausea may be treated with dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) or trimethobenzamide (Tigan). Phenothiazines are not used because of their hepatotoxic effects. People who have been exposed to the patient should be notified so they can receive prophylaxis.

For hepatitis B, drug therapy is used to decrease the viral load, thereby decreasing the disease progression (Table 31-4). In 2008 the Food and DrugAdministration (FDA) approved a once-daily tablet, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Viread), for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. It works by blocking an enzyme required for replication of the virus. The most common side effect is nausea. Chronic hepatitis C virus treatment is also aimed at reducing the viral load. Treatment is supportive to enhance the patient’s natural defenses and promote healing of the liver. Hydration, sufficient rest, and adequate nutrition are the goals. Medication for nausea may be prescribed to encourage adequate nutrition. Vaccines are available to provide active immunity against hepatitis A and B. The vaccine for hepatitis A is administered in two doses, 6 months apart, for lifetime immunity (Dentinger, 2009). The vaccine for hepatitis B produces immunity in about 95% of vaccinated individuals (Degli-Esposti, 2010) and is administered in three or four doses for probable lifetime immunity (MMWR Quick Guide, 2010).

Table 31-4

Table 31-4

Selected Drugs Commonly Prescribed for Disorders of the Liver

| Classification | Action | Nursing Implications | Patient Teaching |

| Diuretic | |||

| Potassium-Sparing Diuretics | |||

| Loop Diuretic | |||

| Laxative: Ammonia Detoxicant | |||

| Antibiotic | |||

| Vasoconstrictor | |||

| Vitamins | |||

| Antiretrovirals | |||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| |||

).

).