Chapter 73 Care of Patients with Breast Disorders

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

2. Describe the three-pronged approach to early detection of breast masses: mammography, clinical breast examination (CBE), and breast self-awareness.

3. Teach a woman who chooses breast self-examination (BSE) as an option to use correct technique.

4. Explain the options available to a person at high genetic risk for breast cancer.

6. Explain the psychosocial aspects related to having breast cancer and undergoing treatments for breast cancer.

7. Discuss sexuality issues with the patient having breast surgery.

8. Describe body image changes that can result from breast cancer surgery.

9. Compare assessment findings associated with benign breast lesions with those of malignant breast lesions.

10. Explain the difference between breast reduction and breast augmentation.

11. Discuss treatment options for breast cancer.

12. Develop a postoperative collaborative plan of care for a patient with breast cancer.

13. Describe the role of radiation and drug therapy in the care of patients with breast cancer.

14. Identify the role of complementary and alternative therapies in breast cancer management.

15. Explain what options are available to a woman considering breast reconstruction.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Video Clip: Inspection (Sitting)

Video Clip: Inspection (Supine)

Benign Breast Disorders

Most breast lumps are benign. Because the incidence of breast disease is related to age, breast disorders are described below in an age-related order (Table 73-1).

TABLE 73-1 TYPICAL PRESENTATION OF BENIGN BREAST DISORDERS

| BREAST DISORDER | DESCRIPTION | INCIDENCE |

|---|---|---|

| Fibroadenoma | Most common benign lesion; solid mass of connective tissue that is unattached to the surrounding tissue | During teenage years into the 30s (most commonly) |

| Fibrocystic breast condition | First stage: Characterized by premenstrual bilateral fullness and tenderness Second stage: Presence of bilateral multi-centric nodules Third stage: Presence of microscopic and macroscopic cysts | Late teens and 20s |

| Ductal ectasia | Hard, irregular mass or masses with nipple discharge, enlarged axillary nodes, redness, and edema; difficult to distinguish from cancer | Women approaching menopause |

| Intraductal papilloma | Mass in duct that results in nipple discharge; mass is usually not palpable | Women 40 to 55 yr of age |

Fibrocystic Breast Condition

Pathophysiology

Fibrocystic changes of the breast include a range of changes involving the lobules, ducts, and stromal tissues of the breast. Because these changes affect at least half of women over the life span, they are referred to as fibrocystic breast condition (FBC) rather than fibrocystic disease. This condition most often occurs in premenopausal women between 20 and 50 years of age and is thought to be caused by an imbalance in the normal estrogen-to-progesterone ratio. Typical symptoms include breast pain and tender lumps or areas of thickening in the breasts. The lumps are rubbery, ill defined, and commonly found in the upper outer quadrant of the breast (Lee, 2009).

Symptoms often resolve after menopause when estrogen decreases.

Ductal Ectasia

• A mass develops that feels hard, has irregular borders, and may be tender.

• A greenish brown nipple discharge, enlarged axillary nodes, and redness and edema over the site of the mass are noted.

Issues of Small-Breasted Women

Action Alert

Action Alert

An important issue for patients who have breast augmentation surgery is breast cancer surveillance. Breast self-examination (BSE) and clinical breast examination (CBE) are easily performed after prostheses are placed. The prosthesis is placed behind the woman’s normal breast tissue, actually pushing it forward. However, screening mammography may not be as sensitive because the amount of visualized breast tissue is decreased. Even though breast cancer detection may be impaired, survival rates for augmented women with breast cancer are not affected (Xie et al., 2010). Likewise, there is no association between breast implants and increased risk for breast cancer (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2010a). Teach women desiring cosmetic breast augmentation about the differences in breast cancer screening.

Gynecomastia

Gynecomastia literally means “female breasts” and is a symptom rather than a disease. It is usually a benign condition of breast enlargement in men (Fig. 73-1). However, gynecomastia can be a result of a primary cancer such as lung or testicular cancer. The enlargement is usually bilateral but may be asymmetric in a few cases. The condition is caused by abnormal growth of the glandular tissue, including the mammary ducts and ductal tissue. In many instances, it is difficult to determine gynecomastia from breast enlargement related to excess adipose tissue. Other causes of gynecomastia include:

• Drugs, such as anti-androgen agents and corticosteroids

• Underlying disease causing estrogen excess, such as malnutrition, liver disease, or hyperthyroidism

• Androgen-deficiency states, such as age, chronic kidney disease, or alcoholism

Breast Cancer

Pathophysiology

Excluding skin cancers, breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women and is second only to lung cancer as a cause of female cancer deaths (ACS, 2010a). Therefore most references in this section are to women with breast cancer. Because of the high incidence of the disease, almost every woman knows of someone with the disease. Thus most women have strong reactions to the threat of breast cancer. These reactions greatly influence health habits, including breast self-examination (BSE) and the patient’s readiness to seek care when a suspicious area is discovered. Nurses play a key role in early detection by educating women about screening guidelines, risk factors for breast cancer, and BSE. Men should also be taught about this disease.

Early detection is the key to effective treatment and survival. The 5-year relative survival rate is lower for women who are diagnosed with an advanced stage of breast cancer. The 5-year survival rate for localized breast cancer is 98%, whereas the rate drops to 84% when the cancer has spread to the regional lymph nodes (ACS, 2010a). Survival drops dramatically when it is metastatic (spread to distant sites).

Cancer of the breast begins as a single transformed cell that grows and multiplies in the epithelial cells lining one or more of the mammary ducts or lobules. It is a heterogeneous disease, having many forms with different clinical presentations and responses to therapy (Weigelt et al., 2010). Some breast cancers will present as a palpable lump in the breast, whereas others will show up only on a mammogram.

There are two broad categories of breast cancer: noninvasive and invasive. About 20% are noninvasive; the remaining 80% are invasive. As long as the cancer remains within the duct, it is noninvasive. The cancer is classified as invasive when it penetrates the tissue surrounding the duct. Most of these cancers arise from the intermediate ducts. Metastasis occurs when cancer cells leave the breast via the blood and lymph systems, which permits spread of these cells to distant sites. The most common sites of metastatic disease from breast cancer are bone, lungs, brain, and liver. The course of metastatic breast cancer is related to the site affected and to the function impaired. The processes involved in cancer development are described in Chapter 24.

Noninvasive Breast Cancers

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is an early noninvasive form of breast cancer. In DCIS, cancer cells are located within the duct and have not invaded the surrounding fatty breast tissue. Because of mammography screening and earlier detection, the number of women diagnosed with DCIS has increased. If left untreated, it may spread into the breast tissue surrounding the ducts over a period of years (invasive breast cancer). Currently there is no way to determine which DCIS lesions will progress to invasive cancer and which ones will remain unchanged, but research is continuing in this area (Muggerud et al., 2010). It is important to remember that although DCIS should be treated to prevent it from developing into an invasive breast cancer, it does not metastasize at this stage.

Another type of noninvasive cancer is lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). This cancer type is rare and usually identified incidentally during biopsy for another problem. Having LCIS increases one’s risk for developing a separate breast cancer later. Traditionally, LCIS has been treated with close observation only. However, emerging evidence suggests that many LCIS lesions will progress to invasive cancer and should be treated with surgical excision (Cangiarella et al., 2008).

Invasive Breast Cancers

The most common type of invasive breast cancer is infiltrating ductal carcinoma. As the name implies, the disease originates in the mammary ducts and grows in the epithelial cells lining these ducts. Once invasive, the cancer grows into the tissue around it in an irregular pattern. If a lump is present, it is felt as an irregular, poorly defined mass. As the tumor continues to grow, fibrosis (replacement of normal cells with connective tissue and collagen) develops around the cancer. This fibrosis may cause shortening of Cooper’s ligaments and the resulting typical skin dimpling that is seen with more advanced disease (Fig. 73-2). Another sign, sometimes indicating late-stage breast cancer, is an edematous thickening and pitting of breast skin called peau d’orange (orange peel skin) (Fig. 73-3).

A rare but highly aggressive form of invasive breast cancer is inflammatory breast cancer (IBC). Symptoms include swelling, skin redness, and pain in the breasts. IBC seldom presents as a palpable lump and may not show up on a mammogram. Because it is usually diagnosed at a later stage than other types of breast cancer, it is often harder to treat successfully (ACS, 2010b).

Breast Cancer in Men

Men usually present with a hard, painless, subareolar mass; gynecomastia may be present. Occasionally the man may have nipple discharge, retraction, erosion, or ulceration. Because men usually do not suspect breast cancer when they feel a lump, diagnosis frequently is delayed (Mattarella, 2010). The disease is often advanced when diagnosed; thus men have poorer survival than women (ACS, 2010a). Treatment of breast cancer in men is the same as in women at a similar stage of disease.

Breast Cancer in Young Women

Approximately 5% of breast cancer cases occur in women younger than 40 years (ACS, 2010a). Genetic predisposition is a stronger risk factor for younger women than older women (Pollán, 2010). Younger women frequently present with more aggressive forms of the disease. Screening tools are often less effective for this group because the breasts are denser. Women of childbearing age with breast cancer may be concerned about infertility after treatment. Distress about interrupted childbearing can have a major impact on their quality of life (Camp-Sorrell, 2009). Nurses should discuss issues of fertility with patients before chemotherapy. Younger women who experience abrupt menopause as a result of chemotherapy or ovarian suppression also report a greater effect on their sexuality than do older counterparts (McLachlan, 2009).

Etiology and Genetic Risk

There is no single known cause for breast cancer. Being an older woman or man is the primary risk factor, although some people are at higher risk than others. Several breast cancer risk factors have been identified; some are modifiable, whereas others are not (ACS, 2010a). Table 73-2 lists major risk factors for breast cancer development.

TABLE 73-2 RISK FACTORS FOR BREAST CANCER

| FACTORS | COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| High Increased Risk (Relative Risk >4.0) | |

| Female gender | Ninety-nine percent of all breast cancers occur in women. |

| Age >50 yr | Greatest risk for women is ages 50 to 69 years. |

| Genetic factors | Inherited mutations of BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 increase risk. |

| Family history | Two or more first-degree relatives with breast cancer at an early age increases risk. |

| History of a previous breast cancer | The risk for developing a cancer in the opposite breast is 5 times greater than for the average population at risk. |

| Breast density | Dense breasts contain more glandular and connective tissue, which increases the risk for developing breast cancer. |

| Moderate Increased Risk (Relative Risk 2.1-4.0) | |

| Family history | One first-degree relative with breast cancer moderately increases risk. |

| Biopsy-confirmed atypical hyperplasia | The overactive growth of cells increases risk. |

| Ionizing radiation | Women who received frequent low-level radiation exposure to the thorax had an increased risk, especially if the exposure occurred during periods of rapid breast formation. |

| High postmenopausal bone density | High estrogen levels over time both strengthen bone and increase breast cancer risk. |

| Low Increased Risk (Relative Risk 1.1-2.0) | |

| Reproductive history Nulliparity OR First child born after age 30 | Childless women have an increased risk, as do women who bear their first child near or after age 30. |

| Menstrual history (Early menstruation or late menopause, or both) | The risk for breast cancer rises as the interval between menarche and menopause increases. Women who undergo bilateral oophorectomy before age 35 have less risk for breast cancer than women who undergo natural menopause. |

| Oral contraceptives | There is a slight increase in breast cancer risk in women taking oral contraceptives. |

| Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) | Use of estrogen and progestin increases risk; routine use of hormone therapy for osteoporosis and heart disease is no longer recommended. |

| Obesity | Postmenopausal obesity (especially increased abdominal fat), increased body mass, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia have been reported to be associated with an increased risk for breast cancer. |

| Other Risk Factors | |

| Alcohol | Risk is dose-dependent; consumption of 3 to 14 drinks per week is associated with a slight increase in risk; risk increases with increased consumption. |

| High socioeconomic status | Breast cancer incidence is greater in women of higher education and socioeconomic background. This relationship is possibly related to lifestyle differences, such as age at first birth. |

| Jewish heritage | Women of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage have higher incidences of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic mutations. |

Modified from American Cancer Society. (2010). Breast cancer facts & figures 2009-2010. Atlanta: Author.

Although most breast cancers occur in women with no family history of the disease, having a first-degree relative (mother, sister, or daughter) with breast cancer increases the risk for the disease. Having more than one first-degree relative or a relative diagnosed at a younger age further increases one’s risk (ACS, 2010a). Certain genetic factors can increase a woman’s risk for both ovarian and breast cancer. Encourage women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer to discuss this history with their physician.

Genetic/Genomic Considerations

Mutations in several genes, such as BRCA1 and BCRA2, are related to hereditary breast cancer. People who have specific mutations in either one of these genes are at a high risk for developing breast cancer as well as ovarian cancer. However, only 5% to 10% of all breast cancers are hereditary. Only women with a strong family history and a reasonable suspicion that a mutation is present have genetic testing for BRCA mutations (ACS, 2010a). Encourage women to talk with a genetics counselor to carefully consider the benefits and potential harmful consequences of genetic testing before these tests are done.

Other causative risk factors not as well explained are nutrition and hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Alcohol is clearly linked to an increased risk for invasive breast cancer. Having an average of one or more alcoholic drinks a day increases the risk up to one and a half times (ACS, 2010a). Obesity also increases breast cancer risk, especially for women after menopause. Fat tissue becomes the major source of estrogen after the ovaries stop functioning. Having a greater amount of fat tissue increases hormonal influence on breast cancer development (ACS, 2010b). An increase in the risk for breast cancer has been shown in postmenopausal women receiving HRT after 5 or more years of use, with the combination of estrogen and progestin carrying the highest increased risk. However, the use HRT is not considered a major risk factor for breast cancer compared with other breast cancer risks (Bluming & Tavris, 2009). Encourage women seeking help for menopausal symptoms to discuss the benefits and risks of hormonal therapy with their health care provider.

Incidence/Prevalence

In 2010, the projected breast cancer incidence was more than 207,000 women in the United States. Of these, almost 40,000 women are likely to die of the disease (Jemal et al., 2010).

One of every 8 U.S. women will develop breast cancer by age 70. Euro-American women older than 40 years are at a greater risk than other racial/ethnic groups, but African-American women younger than 40 years have breast cancer more often than others in that age-group. African-American women have a higher death rate at any age when compared with other women with the disease (ACS, 2010a). This difference has been attributed to limited access to and lower utilization of services for early detection and treatment (ACS, 2010c). Research has also found differences in tumor characteristics in some African-American women (Cunningham et al., 2010). For example, triple negative breast cancer occurs more often in African-American women and younger women. In this type of breast cancer, cells lack receptors for estrogen, progesterone, and the protein HER2. Triple negative breast cancer tends to be more aggressive than other types of breast cancer, and fewer effective treatments exist for it. Much research is ongoing to better understand this type of breast cancer.

For American Indian and Alaska Native women, 5-year survival rates for breast cancer are very poor (English et al., 2008). These women are less likely than non-Hispanic white women to have mammography screening (Wingo et al., 2008). Health promotion interventions to improve mammography rates should consider cultural customs, transportation, and social support.

Latino and Hispanic women have a lower incidence of breast cancer than Euro-American women but a higher death rate (ACS, 2010d).

Risk factors for Hispanic women are not as well understood as those for non-Hispanic whites, and more research is needed in this area (Hines et al., 2010). Whereas Asian women have better 5-year survival rates than Euro-American women, the rates for Native Hawaiian women are slightly poorer than Euro-American women (ACS, 2010a). Strategies that have increased breast cancer screening in the Native Hawaiian population include the use of lay educators and community cancer outreach programs (Aitaoto et al., 2009).

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Health Promotion and Maintenance

The American Cancer Society (ACS) establishes evidence-based guidelines for breast cancer screening in women. Guidelines have not been recommended for screening men in the general population because breast cancer in men is so uncommon (ACS, 2010b). Encourage men with a strong family history or known genetic mutations to discuss screening with their health care provider.

Action Alert

Mammography

The use of mammography (x-ray of the breasts) screening for healthy, average-risk women has been a subject of recent controversy among various scientific and advocacy groups. In 2009, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended against routine screening mammography in average-risk women ages 40 to 49 years and older than 75 years, concluding there is only a small net benefit for women in these age-groups (USPSTF, 2009). Scientific evidence shows there are benefits as well as risks associated with mammography, and disagreement exists about the emphasis that should be placed on each one. However, the ACS and The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) continue to recommend that all women age 40 and older have a screening mammogram annually (ACOG, 2011). Nurses working with women must be able to educate women on the risks and benefits of breast screening techniques so that they can make informed decisions about the screening methods best suited to their individual situations (Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nursing [AWHONN], 2010).

Women with known genetic mutations or other high risk factors for breast cancer should have screening with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in addition to annual mammography (ACS, 2010b). Encourage women with moderate risk factors to discuss with their health care provider the benefits and limitations of adding MRI screening to their annual mammograms. MRI screening is not recommended for women with low breast cancer risk factors.

Breast Self-Awareness/Self-Examination

Some women may want to practice regular breast self-examination (BSE) as a method for breast self-awareness. Evidence shows that monthly BSE is no more beneficial than women simply being aware of what is normal for their own breasts and women are just as likely to find a lump by chance (ACS, 2010b). However, BSE should be presented as an option to women beginning in their early 20s. In addition to breast self-awareness, emphasis should be placed on mammography and clinical breast examination for early detection of breast cancer. The combined approach is better than any single test (ACS, 2010a). A woman who chooses to perform BSE should be taught the correct technique and have it reviewed by a health care professional during her clinical breast examination.

Ensure that the setting in which you demonstrate BSE is private and comfortable. Ask the woman to undress from the waist up, and provide a gown and sheet. Teach the woman to stand in front of a mirror to inspect the breast for abnormalities. She should raise her arms above her head and press her hands on her hips to emphasize any changes in the shape of the breasts. Palpation should be performed in a lying position and while bathing or showering. Before teaching breast palpation, ask the woman to demonstrate her own method. If she is unsure or has not performed BSE before, slowly lead her through the examination while explaining the rationale for the technique and answering questions. Demonstrate the correct technique of examining the breasts with the arm overhead instead of having the arm by her side. Showing the difference in the two positions, especially in large-breasted women, reveals the advantage of using the correct method, which spreads the tissue over the chest wall for more effective palpation (Fig. 73-4).

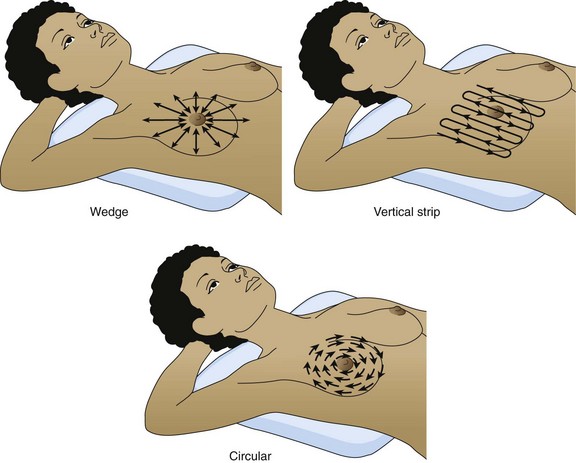

Any one of three palpation methods can be used to examine the breast tissue (Fig. 73-5). Teach the importance of covering all tissue during palpation. Demonstrate the proper amount of pressure needed to palpate the breast tissue and the correct position of the hands. The finger pads, which are more sensitive than the fingertips, are used when palpating the breasts. Teach the woman to press firmly enough to detect the underlying tissue.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree