Chapter 20 Care of Patients with Arthritis and Other Connective Tissue Diseases

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Collaborate with members of the health care team when providing care to patients with arthritis or other connective tissue disease (CTD).

2. Prioritize collaborative interventions for patients with osteoarthritis (OA) and rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Health Promotion and Maintenance

3. Identify community resources to help patients achieve or maintain independence in ADLs.

4. Identify risk factors for the development of arthritis and other CTDs.

5. Teach patients how to protect and exercise their joints and conserve their energy.

6. Teach patients how to prevent Lyme disease and detect it early if it occurs.

7. Assess the patient’s and family’s response to arthritis or other CTD, their support systems, and available resources.

8. Assess the patient’s and family’s sources of stress and coping mechanisms when living with arthritis or other CTD.

9. Compare and contrast the pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of OA and RA.

10. Interpret laboratory findings for patients with RA and other autoimmune CTDs.

11. Apply knowledge of pathophysiology to monitor for and prevent complications of total hip and knee arthroplasty.

12. Teach patients and their families about the postoperative care required after a total joint arthroplasty.

13. Provide information for patients and families about the use and side effects of drug therapy for arthritis or other CTD.

14. Identify the nursing implications associated with drug therapy for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other CTDs.

15. Evaluate and document patient response to drug therapy.

16. Differentiate between discoid lupus erythematosus and systemic lupus erythematosus.

17. Prioritize nursing interventions for patients who have systemic sclerosis.

18. Describe the patient-centered collaborative care of gout based on knowledge of pathophysiology.

19. Explain the differences between polymyositis, systemic necrotizing vasculitis, polymyalgia rheumatica, ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, and Sjögren’s syndrome.

20. Describe current treatment strategies for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome and psoriatic arthritis.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Osteoarthritis

Pathophysiology

• Proteoglycans (glycoproteins containing chondroitin, keratin sulfate, and other substances)

• Collagen (elastic substance)

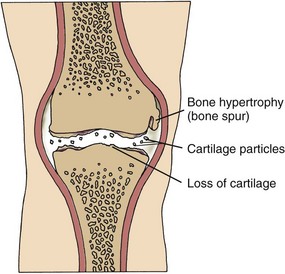

In patients of any age with OA, enzymes, such as stromelysin, break down the articular matrix. In early disease, the cartilage changes from its normal bluish white, translucent color to an opaque and yellowish brown appearance. As cartilage and the bone beneath the cartilage begin to erode, the joint space narrows and osteophytes (bone spurs) form (Fig. 20-1). As the disease progresses, fissures, calcifications, and ulcerations develop and the cartilage thins. Inflammatory cytokines (enzymes) such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) enhance this deterioration. The body’s normal repair process cannot overcome the rapid process of degeneration (McCance et al., 2010).

Etiology and Genetic Risk

Genetic/Genomic Considerations

A classic study reported by Sunk et al. (2007) found a specific genetic link in OA of the knee. They reported that an increase in discoidin domain receptor 2 (DDR-2) expression in diseased joint cartilage was correlated with the degree of tissue damage. The authors concluded that this change occurs after the decrease in proteoglycans from aging. Studies are being conducted to further explore the genetic factors related to OA.

Other factors that can lead to OA are obesity and smoking. Obesity causes joint degeneration, particularly in the knees. Smoking leads to knee cartilage loss, especially in patients with a family history of knee OA. This finding shows a gene-environment interaction in the cause of knee OA (Ding et al., 2007).

Health Promotion and Maintenance

• Keep body weight within normal limits; obesity causes excess wear on joints, especially hips and knees.

• Stop or do not start smoking.

• Avoid or limit activities that promote stress on joints, unless absolutely necessary.

• Limit participation in recreational sports that can damage joints, such as football.

• Wear supportive shoes to prevent falls and damage to foot joints, especially metatarsal joints.

• Do not perform repetitive stress activities, such as knitting or typing, for prolonged periods.

• Avoid risk-taking activities to prevent trauma that can result in OA later in life.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

Patients with OA usually seek medical attention in ambulatory care settings for their joint pain. However, you will also care for those who have OA as a secondary diagnosis in acute and chronic care facilities. Ask the patient about the course of the disease. Collect information specifically related to OA, such as the nature and location of joint pain and how much pain he or she is experiencing. Remember that older patients may underreport pain, resulting in inadequate pain management. Use a 0-to-10 scale or other assessment tool to assess pain intensity. Chapter 5 discusses pain assessment in detail.

Other questions to ask include:

• If joint stiffness has occurred, where and for how long?

• When and where has any joint swelling occurred?

• What do you do to control the pain or stiffness?

• Do you have any loss of function or difficulty in performing ADLs?

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

In the early stage of the disease, the clinical manifestations of OA may appear similar to those of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The distinction between OA and RA becomes more evident as the disease progresses. Table 20-1 compares the major characteristics of both diseases and their common drug therapy.

TABLE 20-1 DIFFERENTIAL FEATURES OF RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS AND OSTEOARTHRITIS

| CHARACTERISTIC | RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS | OSTEOARTHRITIS |

|---|---|---|

| Typical onset (age) | ||

| Gender affected | ||

| Risk factors or cause | ||

| Disease process | ||

| Disease pattern | ||

| Laboratory findings | ||

| Common drug therapy |

ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Severe pain and deformity interfere with ambulation and self-care. In addition to performing a musculoskeletal assessment, collaborate with the physical and occupational therapists to conduct a functional assessment. Assess the patient’s mobility and ability to perform ADLs. Chapter 8 describes functional assessment.

Psychosocial Assessment

OA is a chronic condition that may cause permanent changes in lifestyle. An inability to care for oneself in advanced disease can result in role changes and other losses. Constant pain interferes with quality of life. Chronic pain can also affect sexuality. Patients may not have the energy for sexual intercourse or may find positioning uncomfortable (Gevirtz, 2008).

Planning And Implementation

In 2008, the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) group published evidence-based expert consensus guidelines for patients with knee and hip OA (Zhang et al., 2008). These interdisciplinary best practice guidelines have major implications for nursing care and are reflected in the following discussion.

Managing Chronic Pain

Interventions

Optimal management of patients with OA requires drug therapy and nonpharmacologic measures. If these measures are ineffective, surgery may be performed to reduce pain (Zhang et al., 2008). Perform a pain assessment before and after implementing interventions.

Nonsurgical Management

Management of chronic joint pain is difficult for both the patient and the health care professional. A combination of modalities is often used, including analgesics, rest, positioning, thermal modalities, weight control, and integrative therapies. Chapter 5 elaborates on methods of pain control for chronic pain.

Drug Therapy

Drug Alert

If acetaminophen or topical agents do not relieve pain, the analgesic drug class of choice may be nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) if the patient can tolerate them (see Chart 20-9 later in this chapter). Before beginning NSAID therapy, baseline laboratory information is obtained, including a complete blood count (CBC) and kidney and liver function tests. Celecoxib (Celebrex), a COX-2 inhibitor, is usually the first choice unless the patient has hypertension, renal disease, or cardiovascular disease.

Drug Alert

Nonpharmacologic Interventions

• Local rest involves immobilizing any unstable joint, most often the knee, with a brace or splint. Knee braces improve balance, prevent falls, and decrease pain. If needed, the patient should use an ambulatory aid, such as a cane, to decrease stress on weight-bearing joints. The cane should be used on the strongest side of the body. Collaborate with the physical therapist (PT) to fit the patient for the appropriate device and explain its use.

• Systemic rest refers to immobilizing the entire body, such as during a nap. Teach the patient about the importance of sleeping about 8 to 10 hours and, if possible, resting an additional 1 to 2 hours each day.

• Psychological rest is equally important because it allows relief from the daily stresses that can enhance pain.

Action Alert

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

A variety of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies, especially acupuncture, have been effective for some patients (see Chapter 2). Topical capsaicin products may also be used. This expensive OTC drug may work by blocking substance P, a neurotransmitter for pain. Tell the patient to expect a burning sensation for a short time after applying capsaicin. Recommend the use of plastic gloves for application. To prevent burning of eyes or other body areas, wash hands immediately after applying the substance.

Dietary supplements may complement traditional drug therapies. Glucosamine and chondroitin are widely used and are the most effective nonprescription supplements taken to decrease pain and improve functional ability (Zhang et al., 2008). These natural products are found in and around bone cartilage for repair and maintenance. Glucosamine may decrease inflammation, and chondroitin may play a role in strengthening cartilage. These supplements may be used topically or taken in oral form. If no improvement is evident in 6 months of use, they should be discontinued (Zhang et al., 2008). Chart 20-1 summarizes what you should teach your patients about glucosamine, with or without chondroitin.

Chart 20-1 Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Considerations for Taking Glucosamine Supplements

• Tell your health care provider if you decide to take glucosamine.

• Do not take glucosamine if you have hypertension.

• Do not take glucosamine if you are pregnant or breast-feeding.

• Monitor for bleeding if you take chondroitin with glucosamine or chondroitin alone if you are on anticoagulant therapy.

• If diabetic, monitor your blood glucose levels carefully because taking glucosamine for a prolonged time can increase them.

• Be aware that glucosamine can cause adverse effects such as a rash; GI disturbances, especially diarrhea; drowsiness; and headache.

• Be sure to take the recommended dosage based on your weight.

• Read drug labels to ensure that you do not take too much glucosamine for your weight; some drug names may not indicate they contain glucosamine (e.g., Bioflex, Arth-X Plus, Nutri-Joint).

Surgical Management

A less invasive procedure using arthroscopy may be used to remove damaged cartilage (see Chapter 52). An osteotomy (bone resection) may be performed to correct joint deformity, but this procedure is done most commonly for younger adults (Zhang et al., 2008).

Patient-Centered Care; Evidence-Based Practice

1. What additional physical assessment do you need to perform to determine her level of functioning?

2. What other evidence-based interventions for OA pain might you recommend?

3. How might this patient’s OA affect her ability to use crutches after surgery?

4. What health teaching is needed for this patient to help manage her OA and use crutches while her ankle heals?

Total Hip Arthroplasty

An interdisciplinary plan of care that outlines expectations during preadmission, hospitalization, and posthospitalization phases of care should be reviewed with the patient and family or significant other. Thomas and Sethares (2008) investigated the effects of preoperative interdisciplinary patient education for patients having total hip or knee arthroplasty using a large quasi-experimental design. The researchers found that postoperative patients in the intervention group had a higher knowledge level than those patients who did not receive the structured preoperative education. A study by Almada and Archer (2009) described the positive outcomes for joint arthroplasty patients who were visited by an RN before and after surgery. Part of both visits included patient and family/caregiver education.

In some hospitals or orthopedic office practices, the physical therapist (PT) may have the patient practice transfers, positioning, and ambulation. An occupational therapist (OT) may partner with the PT to assist in exercises or learning to ambulate with an assistive device, such as crutches or a walker. In a systematic review of three available studies, Barbay (2009) found that preoperative exercises for patients having hip or knee arthroplasty had some benefits in improving postoperative outcomes, but the results were inconclusive.

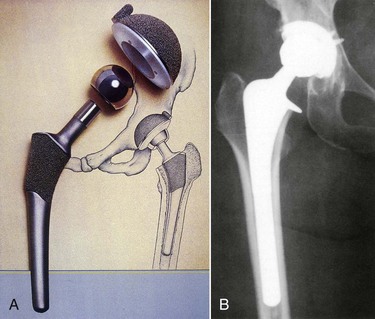

Regardless of procedure type, two components are used in the THA—the acetabular component and the femoral component (Fig. 20-2). A non-cemented prosthesis is most often used. Bone surfaces are smoothed as they are prepared to receive the artificial components. The non-cemented components are press-fitted into the prepared bone. The acetabular cup may be placed using computer assistance. If the prosthesis is cemented, polymethyl methacrylate (an acrylic fixating substance) is used. A closed wound drainage system may be placed in the wound before the surgeon closes the incision.

FIG. 20-2 A, Two major components of total hip arthroplasty. B, X-ray showing the components in place.

In addition to providing the routine postoperative care discussed in Chapter 18, assess for and help prevent possible postoperative complications. Table 20-2 summarizes these complications, including nursing measures for prevention, assessment, and intervention. Chart 20-2 highlights special concerns for the care of older adults in the postoperative period. Collaborate with your patient and his or her family to become safety partners to keep the patient free from harm, including complications, such as:

TABLE 20-2 NURSING INTERVENTIONS TO PREVENT COMPLICATIONS OF TOTAL JOINT ARTHROPLASTY

| COMPLICATION | PREVENTION/INTERVENTION |

|---|---|

| Dislocation | |

| Infection | |

| Venous thromboembolism | |

| Hypotension, bleeding, or infection |

Chart 20-2 Nursing Focus on the Older Adult

Postoperative Care of the Older Adult with a Total Hip Arthroplasty

• Use an abduction pillow or splint to prevent adduction after surgery if the patient is very restless or has an altered mental state.

• Keep the patient’s heels off the bed to prevent pressure ulcers.

• Do not rely on fever as a sign of infection; older patients often have infection without fever. Decreasing mental status typically occurs when the patient has an infection.

• When assisting the patient out of bed, move him or her slowly to prevent orthostatic (postural) hypotension.

• Encourage the patient to deep breathe and cough and to use the incentive spirometer every 2 hours to prevent atelectasis and pneumonia.

• As soon as permitted, get the patient out of bed to prevent complications of immobility.

• Anticipate the patient’s need for pain medication, especially if he or she cannot verbalize the need for pain control.

• Expect a temporary change in mental state immediately after surgery as a result of the anesthetic and unfamiliar sensory stimuli. Reorient the patient frequently.

A major complication of THA is subluxation (partial dislocation) or total dislocation.

Action Alert

Teach the patient and family about other precautions to prevent dislocation as outlined in Chart 20-3. In addition to preventing adduction, remind them that the patient should avoid flexing the hips more than 90 degrees at all times. Use diagrams or demonstrate correct positioning to help reinforce this information before the patient gets out of bed (Fig. 20-3).

Chart 20-3 Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Care of Patients with Total Hip Arthroplasty After Hospital Discharge

Hip Precautions

• Do not sit or stand for prolonged periods.

• Do not cross your legs beyond the midline of your body.

• Do not bend your hips more than 90 degrees.

• Do not twist your body when standing.

• Use an ambulatory aid, such as a walker, when walking.

• Use assistive/adaptive devices for dressing, such as for putting on shoes and socks.

• Do not put more weight on your affected leg than allowed.

• Resume sexual intercourse as usual on the advice of your surgeon.

Other Care

• Continue walking and performing the leg exercises as you learned in the hospital.

• Do not cross your legs to help prevent blood clots.

• Report pain, redness, or swelling in your legs to your physician immediately.

• Report chest pain or shortness of breath to your physician immediately.

• If you are taking an anticoagulant, follow the precautions learned in the hospital to prevent bleeding; avoid using a straight razor, avoid injuries, and report bleeding or excessive bruising to your surgeon immediately.

• Perform postoperative exercises as instructed, including straight leg raises, gluteal sets, ankle pumps, and “ham” sets.

Critical Rescue

Preventing Venous Thromboembolism

Fondaparinux (Arixtra), a factor Xa inhibiting agent, may also be prescribed for patients undergoing hip and knee arthroplasty. Its action is similar to that of LMWHs and has no effect on coagulation tests. Like other drugs, however, the patient is at risk for bleeding. No antidote exists at this time for fondaparinux. Like LMWHs, Arixtra is given for several days with an overlap while anticoagulants begin to work. A complete discussion of nursing care associated with patients taking anticoagulants and VTE is found in Chapter 38. The Joint Commission’s VTE Core Measures are also discussed in that chapter.

Although hip arthroplasty is performed to relieve joint pain, patients experience pain related to the surgical procedure. Many state that their pain is different and less severe than before surgery. Immediate pain control is typically achieved by extended-release epidural morphine (EREM) or patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with morphine or another opioid. A study by Smith-Miller et al. (2009) found that there was no difference in pain control when these two methods were compared. Chapter 5 contains information on the nursing care associated with these acute pain modalities. Keep in mind that the patient may also receive other analgesics or anti-inflammatory drugs for chronic arthritic pain in other joints.

Nonpharmacologic methods for acute and chronic pain control can also be used to decrease the amount of drug therapy used (see Chapter 5). A study by Thomas and Sethares (2010) found that guided imagery can be helpful in controlling pain in patients with total joint arthroplasty.

Promoting Mobility and Activity

Action Alert

Remind the patient to avoid flexing the hips beyond 90 degrees as discussed earlier (see Fig. 20-3). Raised toilet seats and reclining chairs help prevent hyperflexion of the replaced hip joint. Be sure to teach the patient to also avoid twisting the body or crossing his or her legs to prevent hip dislocation.

Discharge for patients having traditional surgery may be to the home, a rehabilitation unit, a transitional care unit, or a skilled unit or long-term care facility for continued rehabilitation before discharge to home. The interdisciplinary team provides written instructions for posthospital care and reviews them with patients and their family members (see Chart 20-3). Be sure to provide a copy of these instructions for the patient.

Total Knee Arthroplasty

Postoperative nursing care of the patient with a TKA is similar to that for the patient with a total hip arthroplasty; however, maintaining hip abduction is not necessary. The surgeon may prescribe a CPM machine, which can be applied in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) or soon after the patient is admitted to the postoperative unit (Fig. 20-4). The CPM machine keeps the prosthetic knee in motion and may prevent the formation of scar tissue, which could decrease knee mobility and increase postoperative pain. In the immediate postoperative period, the surgeon may also prescribe ice packs or other cold therapy to decrease swelling at the surgical site. Swelling and bruising are more common with this type of surgery than with hip surgery.

The surgeon, PT, or technician presets the CPM machine for the appropriate range of motion and cycles per minute. A typical initial setting is 20 to 30 degrees of flexion and full extension (0 degrees) at two cycles per minute, but this setting varies according to surgeon preference. The machine is generally used on an intermittent schedule of a designated number of hours several times a day, with the range of motion increased gradually. Observe and document the patient’s response to the device, and follow the surgeon’s protocol for settings. Chart 20-4 outlines your responsibility when caring for a patient using the CPM machine.

Chart 20-4 Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

The Patient Using a Continuous Passive Motion (CPM) Machine

• Ensure that the machine is well padded.

• Check the cycle and range-of-motion settings at least once every 8 hours.

• Ensure that the joint being moved is properly positioned on the machine.

• If the patient is confused, place the controls to the machine out of his or her reach.

• Assess the patient’s response to the machine.

• Turn off the machine while the patient is having a meal in bed.

• When the machine is not in use, do not store it on the floor.

One of the most recent advances in postoperative pain management for lower extremity total joint arthroplasty is peripheral nerve blockade (PNB). In this procedure, the anesthesiologist injects the femoral or sciatic nerve with local anesthetic; the patient may receive a continuous infusion of the anesthetic by portable pump. This method of pain management not only decreases pain but also allows patients to participate in rehabilitation earlier than when using opioid analgesia alone. Patients having continuous femoral nerve blockade (CFNB) after TKA require less opioids and antiemetics when compared with patients receiving no CFNB and those who had a single-shot FNB. A study by Leach and Bonfe (2009) also found that patients with nerve blocks had better flexion and extension of the knee when compared with those who had either general or epidural/spinal anesthesia.

Critical Rescue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree