Chapter 40 Care of Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Plan continuity of care between health care agencies or hospital and home when discharging patients who have had cardiac interventions or surgeries.

2. Explain the role of the interdisciplinary team in cardiac rehabilitation.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

3. Differentiate between modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD).

4. Develop a teaching plan for patients at risk for CAD regarding cardiovascular risk modification programs and lifestyle changes.

5. Assess patient and family responses to acute coronary events, especially myocardial infarction (MI).

6. Compare and contrast the clinical manifestations of stable angina, unstable angina, and MI.

7. Interpret physical and diagnostic assessment findings in patients who have CAD.

8. Prioritize nursing care for patients who have chest pain.

9. Teach patients and families about drug therapy for CAD.

10. Explain the nursing care for patients who have thrombolysis for an MI.

11. Develop a plan of care for the patient who has a percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

12. Delineate postoperative care for the patient who has coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, including monitoring for complications.

13. Identify the special needs of older adults having coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

14. Differentiate care for patients having traditional CABG surgery, minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass, off-pump CABG, and transmyocardial laser revascularization.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Acute Coronary Syndrome

Animation: Coronary Artery Bypass Graft

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Pathophysiology

Acute Coronary Syndromes

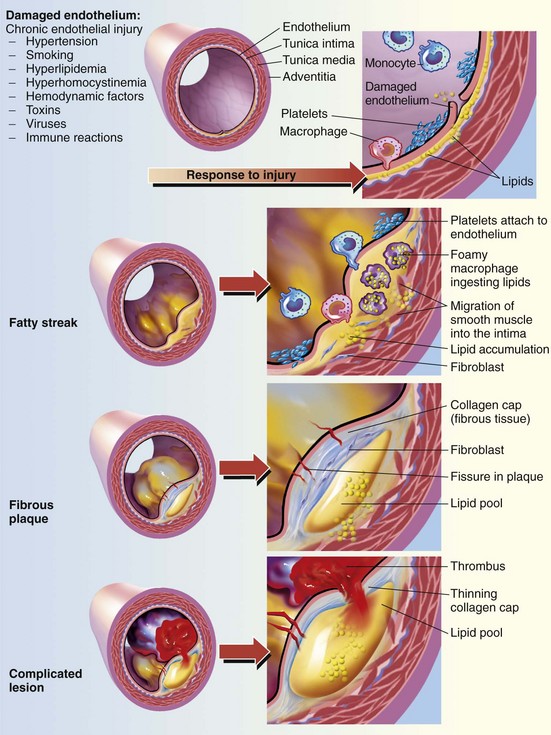

The term acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is used to describe patients who have either unstable angina or an acute myocardial infarction. In ACS, it is believed that the atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary artery ruptures, resulting in platelet aggregation (“clumping”), thrombus (clot) formation, and vasoconstriction (Fig. 40-1). The amount of disruption of the atherosclerotic plaque determines the degree of coronary artery obstruction (blockage) and the specific disease process. The artery has to have at least 40% plaque accumulation before it starts to block blood flow.

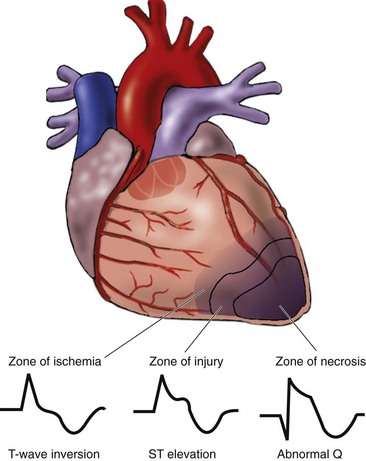

Historically, an acute myocardial infarction (MI) was diagnosed by the presence of ST-segment elevation on the 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) (see discussion of the normal ECG in Chapter 36). However, all patients do not present with this finding. Instead, they are classified into one of three categories according to the presence or absence of ST-segment elevation on the ECG and positive troponin markers (see Chapter 35 for discussion of troponins):

• ST-elevation MI (STEMI) (traditional manifestation)

• Non–ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI) (common in women)

Myocardial Infarction

The most serious acute coronary syndrome is myocardial infarction (MI), often referred to as acute MI or AMI. Undiagnosed or untreated angina can lead to this very serious health problem. AMI is further divided by the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/AHA into non–ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI) and ST-elevation MI (STEMI) (Anderson, 2007). Patients presenting with NSTEMI typically have ST and T-wave changes on 12-lead ECG. This indicates myocardial ischemia. Cardiac enzymes may be initially normal but elevate over the next 6 to 12 hours. Patients presenting with STEMI typically have ST elevation in two contiguous leads on a 12-lead ECG. This indicates myocardial infarction/necrosis and requires immediate treatment.

Often MIs begin with infarction of the subendocardial layer of cardiac muscle. This layer has the longest myofibrils in the heart, the greatest oxygen demand, and the poorest oxygen supply. Around the initial area of infarction (zone of necrosis) in the subendocardium are two other zones: (1) the zone of injury—tissue that is injured but not necrotic; and (2) the zone of ischemia—tissue that is oxygen deprived. This pattern is illustrated in Fig. 40-2.

Many women with symptomatic ischemic heart disease or abnormal stress testing do not have normal coronary angiography (Shaw et al., 2009). Studies implicate microvascular disease or endothelial dysfunction or both as the causes for risk for CAD in women. Endothelial dysfunction is defined as the “inability of the arteries and arterioles to dilate due to inability of the endothelium to produce nitric oxide, a relaxant of vascular smooth muscle” (Bellasi et al., 2007).

Women typically have smaller coronary arteries and frequently have plaque that breaks off and travels into the small vessels to form an embolus (clot). “Positive remodeling” or outward remodeling (lesions that protrude outward) is more common in women (Bellasi et al., 2007). This outpouching may be missed on coronary angiography.

The patient’s response to an MI also depends on which coronary artery or arteries were obstructed and which part of the left ventricle wall was damaged: anterior, septal, lateral, inferior, or posterior. Fig. 35-3 in Chapter 35 shows the location of the major coronary arteries.

Etiology and Genetic Risk

Atherosclerosis is the primary factor in the development of CAD. Numerous risk factors contribute to atherosclerosis and subsequently to CAD (also see Chapter 38).

Nonmodifiable risk factors are personal characteristics that cannot be altered or controlled. These risk factors, which interact with each other, include age, gender, family history, and ethnic background. People with a family history of CAD are at high risk for developing the disease. These factors are discussed in more detail in Chapter 35.

Age is the most important risk factor for developing CAD in women. The older a women is, the more likely she will have the disease. When compared with men, women are usually 10 years older when they have CAD. In addition, women who have MIs have a greater risk for dying during hospitalization. When they are older than 40 years, women are more likely than men to die within 1 year after their MI (AHA, 2010).

Incidence/Prevalence

According to the American Heart Association (AHA) (2010), 64% of women and 50% of men who had a myocardial infarction (MI) (“heart attack”) were not aware that they had CAD. The average age of a person having a first MI is 64.5 years for men and 70.3 years for women (AHA, 2010). Almost 30% of patients who have an MI die within 5 years after the event (AHA, 2010).

Every 25 seconds, a person in the United States has a major coronary event and 452,000 people die each year from an MI. Many people die from coronary heart disease without being hospitalized. Most of these are sudden deaths caused by cardiac arrest (AHA, 2010).

Premenopausal women have a lower incidence of MI than men. However, for postmenopausal women in their 70s or older, the incidence of MI equals that of men. Family history is also a risk factor for women; those whose parents had CAD are more susceptible to the disease. Women with abdominal obesity (androidal shape) and metabolic syndrome (described on p. 834) are also at increased risk for CAD (Bellasi et al., 2007).

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Ninety-five percent of sudden cardiac arrest victims die before reaching the hospital, largely because of ventricular fibrillation (“v fib”). To help combat this problem, automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) are found in many public places, such as in shopping centers and on airplanes. Employees are taught how to use these devices if a sudden cardiac arrest occurs. Some patients with diagnosed CAD have AEDs in their homes or at work. How to use this device is described on p. 738 in Chapter 36.

Action Alert

For patients at risk for coronary artery disease (CAD), especially MI, assess specific risk factors and implement an individualized health teaching plan. Teach people who have one or more of these risk factors the importance of modifying or eliminating them to decrease their chances of CAD (Chart 40-1).

Chart 40-1 Patient and Family Education

Preparing for Self-Management: Prevention of Coronary Artery Disease

Physical Activity

• If you are middle-aged or older or have a history of medical problems, check with your health care provider before starting an exercise program.

• Appropriate exercise should be enjoyable, burn 400 calories per session, and sustain a heart rate of 120 to 150 beats/min, depending on your age.

• Exercise periods should be at least 20 to 30 minutes long with 10-minute warm-up and 5-minute cool-down periods.

• If you cannot exercise moderately three to five times each week, walk daily for 30 minutes at a comfortable pace.

• If you cannot walk 30 minutes daily, walk any distance you can (e.g., park farther away from a site than necessary; use the stairs, not the elevator, to go one floor up or two floors down).

Several groups have a higher genetic risk for CAD than others. African-American and Hispanic women have higher CAD risk factors than white women of the same socioeconomic status. Of American Indians and Alaskan Natives 18 years of age and older, about 64% of men and 81% of women have one or more CAD risk factors (hypertension [HTN], smoking, high cholesterol, excess weight, or diabetes mellitus). The leading cause of death for both men and women in the Euro-American population is cardiac disease, even though they may not have genetic predispositions to developing cardiovascular risk factors (AHA, 2010).

Reducing Elevated Serum Lipid Levels

The risk for CAD rises as serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels increase. In addition to measuring the total serum cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglyceride (TG) levels are important in assessing risk for CAD. LDL cholesterol is the “bad” type, and HDL cholesterol is referred to as “good” because it has protective properties. Elevated levels of LDL combined with low levels of HDL increase the risk for MI. Total serum cholesterol levels also put the patient at a higher risk for developing an MI. According to the AHA (2010), a 10% reduction in serum cholesterol may result in a 30% reduction in the incidence of CAD and MI. The fasting total cholesterol should be below 130 mg/dL. The AHA (2010) defines levels of fasting total cholesterol as:

The desired LDL level in patients who are at high risk or have existing CAD is less than 70 mg/dL. For patients at low or moderate risk, LDL should also be substantially less than 100 mg/dL (AHA, 2010). HDL cholesterol levels should be above 40 mg/dL, although this recommendation may soon be changed to a higher level. The recommended triglyceride level is less than 135 mg/dL in women and 150 mg/dL in men (Pagana & Pagana, 2010).

Using Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Teach patients that adding omega-3 fatty acids from fish and plant sources has been effective for some patients in reducing lipid levels, stabilizing atherosclerotic plaques, and reducing sudden death from an MI. The preferred source of omega-3 acids is from fish three times a week or a daily fish oil nutritional supplement (1-2 g/day) containing eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) (AHA, 2010). Plant sources (flaxseed, flaxseed oil, walnuts, and canola oil) contain α-linolenic acid, and the conversion of α-linolenic acid to EPA and DHA is not as efficient in patients who consume a typical Western diet (Surette, 2008). Lovaza (omega-3 fatty acids) is a new medication approved by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) and is used to reduce very high triglycerides (>500 mg/dL) levels. Lovaza has not been proven to prevent heart attacks or stroke.

Eliminating Tobacco Use

In the United States, an estimated 23% of men and 18% of women smoke cigarettes, putting them at increased risk for MI (AHA, 2010). About five million U.S. men and women chew tobacco, with the highest rates in the South and rural areas. Tobacco use and passive smoking from “second-hand smoke” (also called environmental smoke) substantially reduce blood flow in the coronary arteries.

Tobacco use, especially cigarette smoking, accounts for over one third of deaths from CAD. It enhances the process of atherosclerosis through mechanisms that are still poorly understood. Nicotine begins the release of catecholamines, resulting in an increased heart rate and peripheral vasoconstriction. This action causes increases in blood pressure (BP), cardiac afterload, and oxygen consumption. Cigarette smoking has also been found to cause endothelial dysfunction and increased vessel wall thickness. This process increases the risk for clot formation and vessel occlusion. The resulting hypertension may exacerbate the atherosclerotic process by increasing vessel wall permeability. Another problem with cigarette smoking is the production of carbon monoxide, which has been found to decrease the oxygen content in arterial blood. The good news is that when cigarette smoking is stopped, the risk for CAD decreases. A person who stops smoking may decrease the risk for CAD by as much as 80% in 1 year. Reducing the tar and nicotine content of the cigarettes smoked does not reduce the risk for CAD (AHA, 2010).

Ask about tobacco use, and advise the tobacco user and family members who smoke to quit using this harmful substance. Teach all patients to avoid environmental tobacco smoke at work and at home if at all possible. Additional information about tobacco use and smoking cessation is found in Chapters 32 and 35.

Increasing Physical Activity

Physical inactivity may be the most important risk factor for the general population. Less-active, less-fit people have a 30% to 50% greater risk for developing high blood pressure (BP), which predisposes to CAD. Physical inactivity is more common among women than men, among African Americans and Hispanics than Euro-Americans, among older adults than younger adults, and among the less affluent than the more affluent (AHA, 2010). The causes for these differences are not known. Teach patients that regular physical activity helps maintain body weight and muscle mass while improving BP and lipid values.

Managing Other Factors

One in three Americans has hypertension (HTN). This disease increases the workload of the heart, which increases the risk for MI. The cause of primary HTN is not known. However, it is easily detected and usually controllable. About half of patients having a first MI have a BP greater than 160/95 mm Hg. Ways to manage hypertension and therefore reduce the risk for CAD are described in Chapter 38.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a major risk factor for heart disease. A woman with diabetes mellitus is twice as likely to develop CAD than a woman without DM. Heart disease is the leading cause of diabetic-related death in both men and women. Most adults with diabetes also have hypertension. Chapter 67 discusses vascular complications of diabetes in detail.

Alcohol may help prevent or contribute to the development of CAD, depending on the amount consumed. Excessive consumption, described as having more than 3 ounces (90 mL) per day, can lead to increased heart disease, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome, described in the next section. A lower amount may help prevent CAD (Suzuki et al., 2009).

Modifiable risk factors vary for people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Some of the differences may be explained by lack of access to health care for some groups or by genetic factors. American Indians, for example, have the highest percentage of smokers among women and men. However, many of these people have poor access to care or have language barriers in a predominantly English-speaking, Euro-American health care system. Nutritional preferences may also explain some of the differences. For instance, according to the AHA (2010), high cholesterol is more common in African-American and Hispanic populations. Diets higher in fat and cholesterol are often less expensive and may be a factor in explaining differences, and obesity is more common in these groups. Genetic factors may also contribute to the differences among ethnic groups.

Metabolic syndrome, also called syndrome X, has been recognized as a risk factor for cardiovascular (CV) disease and is being aggressively researched. Patients who have three of the factors in Table 40-1 are diagnosed with metabolic syndrome. This health problem increases the risk for developing diabetes and CAD. About 47 million people in the United States have metabolic syndrome (AHA, 2010). This increase is likely due to physical inactivity and the current obesity epidemic. Management is aimed at reducing risks, managing hypertension, and preventing complications.

TABLE 40-1 INDICATORS OF RISK FACTORS FOR METABOLIC SYNDROME

| RISK FACTOR | INDICATOR |

|---|---|

| Hypertension | Either blood pressure of 130/85 mm Hg or higher or taking antihypertensive drug(s) |

| Decreased HDL-C (usually with high LDL-C) level | Either HDL-C <40 mg/dL for men or <50 mg/dL for women or taking an anticholesterol drug |

| Increased level of triglycerides | Either 150 mg/dL or higher or taking an anticholesterol drug |

| Increased fasting blood glucose (due to diabetes, glucose intolerance, or insulin resistance) | Either 100 mg/dL or higher or taking antidiabetic drug(s) |

| Large waist size (excessive abdominal fat causing central obesity) | 40 inches (102 cm) or greater for men or 35 inches (89 cm) or greater for women |

HDL-C, High-density lipoprotein–cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein–cholesterol.

Elevated levels of serum homocysteine, an amino acid, have been associated with an increased incidence of CAD. However, research findings are not consistent regarding its risk. Vitamin B supplements have been thought to decrease homocysteine. Recent studies suggest that vitamin B is not effective as secondary prevention, but few studies have been conducted on vitamin B as a primary preventive measure (Ebbing et al., 2008).

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

African Americans and women tend to delay seeking treatment for MI and therefore have higher mortality rates than Euro-Americans. One contributing factor to this delay is a greater incidence of dyspnea as an acute symptom among these groups rather than the classic pain more typical of other groups (AHA, 2010).

Chart 40-2 compares and contrasts angina and infarction pain. Because angina pain is ischemic pain, it usually improves when the imbalance between oxygen supply and demand is resolved. For example, rest reduces tissue demands and nitroglycerin improves oxygen supply. Discomfort from a myocardial infarction (MI) does not usually resolve with these measures. Also ask about any associated symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diaphoresis, dizziness, weakness, palpitations, and shortness of breath.

Laboratory Assessment

Although there is no single ideal test to diagnose MI, the most common laboratory tests include troponins T and I, creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), and myoglobin. These cardiac markers are specific for MI and cardiac necrosis. Troponins T and I and myoglobin rise quickly. CK-MB is the most specific marker for MI but does not peak until about 24 hours after the onset of pain. These tests are described in more detail in Chapter 35.

Imaging Assessment

Use of the 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA) has been found to be helpful in diagnosing coronary artery disease in symptomatic patients identified as having a “low- or intermediate-pretest probability” risk for CAD. This new generation of high-speed computed tomography (CT) scanners is becoming a highly reliable, noninvasive way to evaluate CAD (Weustink et al., 2010).

Other Diagnostic Assessment

After the acute stages of an angina episode or MI, the health care provider often requests an exercise tolerance test (stress test) on a treadmill to assess for ECG changes consistent with ischemia, evaluate medical therapy, and identify those who might benefit from invasive therapy. Pharmacologic stress-testing agents such as dobutamine (Dobutrex) may be used instead of the treadmill. Treadmill exercise testing is only moderately accurate for women when compared with men (Bellasi et al., 2007). In women with suspected CAD, stress echocardiography or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) should be performed.

Cardiac catheterization may be performed to determine the extent and exact location of coronary artery obstructions. It allows the cardiologist and cardiac surgeon to identify patients who might benefit from percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) and stent placement or from coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Each of the diagnostic tests in this section is described in detail in Chapter 35.

Analysis

The priority problems for most patients with CAD are:

1. Acute Pain related to imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand

2. Inadequate tissue perfusion (cardiopulmonary) related to interruption of arterial blood flow

3. Activity Intolerance related to fatigue caused by imbalance between oxygen supply and demand

4. Ineffective Coping related to effects of acute illness and major changes in lifestyle

For the patient experiencing an MI, additional problems include:

Planning and Implementation

Managing Acute Pain

Interventions

Evaluate any report of pain, obtain vital signs, ensure an IV access, and notify the health care provider of the patient’s condition. Chart 40-3 summarizes the emergency interventions for the patient with symptoms of CAD.

Chart 40-3 Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

Emergency Care of the Patient with Chest Discomfort

• Assess airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs). Defibrillate as needed.

• Provide continuous ECG monitoring.

• Obtain the patient’s description of pain or discomfort.

• Obtain the patient’s vital signs (blood pressure, pulse, respiration).

• Assess/provide vascular access.

• Consult chest pain protocol or notify the physician or Rapid Response Team for specific intervention.

• Obtain a 12-lead ECG within 10 minutes of reports of chest pain.

• Provide pain relief medication and aspirin as prescribed.

• Administer oxygen therapy to maintain oxygen saturation ≥95%.

• Remain calm. Stay with the patient if possible.

• Assess the patient’s vital signs and intensity of pain 5 minutes after administration of medication.

• Remedicate with prescribed drugs (if vital signs remain stable), and check the patient every 5 minutes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree