Chapter 75 Care of Male Patients with Reproductive Problems

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Identify health care team members to provide collaborative care and discharge planning for patients with male reproductive problems.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

2. Teach men and their partners about community resources for reproductive cancers.

3. Evaluate patient risk factors for male reproductive cancers.

4. Develop a health teaching plan for men to prevent or detect early male reproductive cancers.

5. Assess the patient’s acceptance of body image changes that may result from male reproductive surgery.

6. Explain the psychosocial needs of men who have male reproductive problems.

7. Perform a focused physical assessment of the man’s reproductive system.

8. Describe the mechanisms of action, side effects, and nursing implications for pharmacologic management of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

9. Develop a postoperative plan of care for a patient undergoing surgery for benign prostatic hyperplasia.

10. Incorporate complementary and alternative therapies into the patient’s plan of care.

11. Discuss treatment options for prostate cancer with patients, partners, and/or families.

12. Provide preoperative teaching for patients having a radical prostatectomy.

13. Develop a teaching plan for the patient and family about the role of drug therapy in treating prostate cancer.

14. Identify adverse effects of radiation therapy for reproductive cancers.

15. Develop a community-based plan of care for a man with prostate cancer.

16. Describe the options for treating erectile dysfunction.

17. Discuss cultural considerations related to male reproductive problems.

18. Develop a plan of care for a patient with testicular cancer, including fertility issues.

19. Compare the assessment and treatment for hydrocele, spermatocele, and varicocele.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

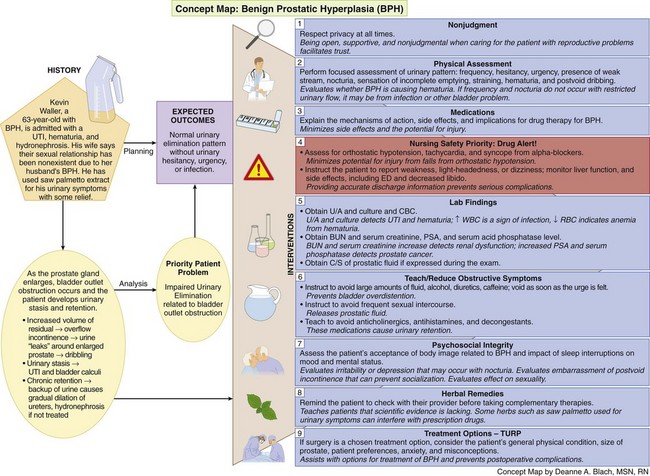

Concept Map: Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Pathophysiology

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a very common health problem, but the exact cause is unclear. It is likely the result of a combination of aging and the influence of androgens that are present in prostate tissue, such as dihydrotestosterone (DHT) (McCance et al., 2010). With aging and increased DHT levels, the glandular units in the prostate undergo nodular tissue hyperplasia (an increase in the number of cells). This altered tissue promotes local inflammation by attracting cytokines and other substances (McCance et al., 2010).

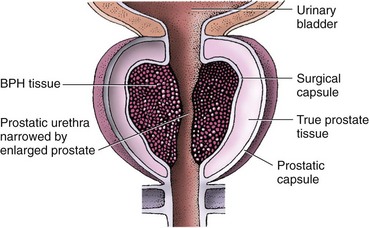

As the prostate gland enlarges, it extends upward into the bladder and inward, causing bladder outlet obstruction (Fig. 75-1). In response, the urinary system is affected in several ways. First, the detrusor (bladder) muscle thickens to help urine push past the enlarged prostate gland (McCance et al., 2010). In spite of the bladder muscle change, the patient has increased residual urine (stasis) and chronic urinary retention. The increased volume of residual urine often causes overflow urinary incontinence, in which the urine “leaks” around the enlarged prostate causing dribbling. Urinary stasis can also result in urinary tract infections and bladder calculi (stones).

In a few patients, the prostate becomes very large and the man cannot void (acute urinary retention [AUR]). The patient with this problem requires emergent care. In other patients, chronic urinary retention may result in a backup of urine and cause a gradual dilation of the ureters (hydroureter) and kidneys (hydronephrosis) if BPH is not treated. These problems can lead to chronic kidney disease as described in Chapter 71.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

History

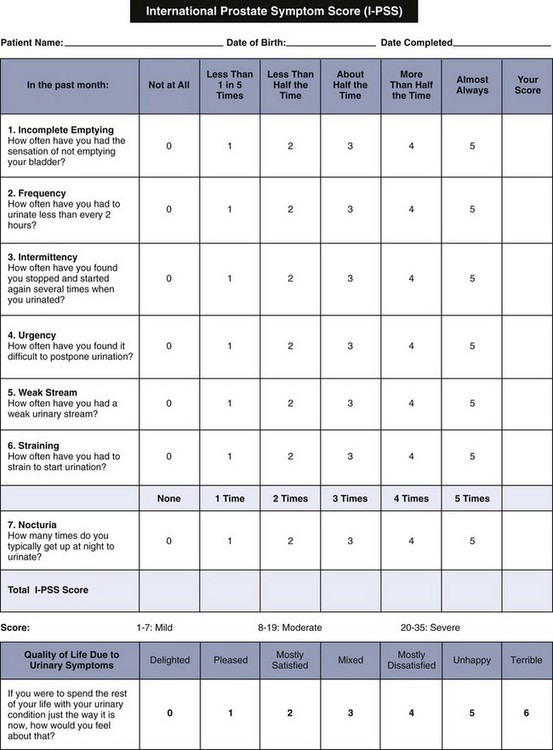

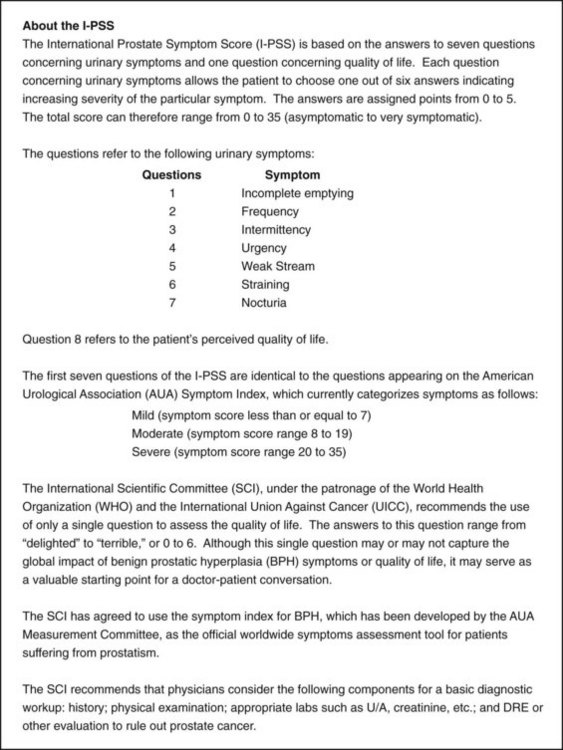

When taking a history, several standardized assessment tools are used to help the health care provider determine the severity of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) associated with prostatic enlargement. One of the most commonly used assessments is the International Prostate Symptom Score (I-PSS), which incorporates the American Urological Association Symptom Index (AUA-SI) (Fig. 75-2) as questions 1 through 7. The additional question included on the I-PSS is the effect of the patient’s urinary symptoms on quality of life. Most patients complete the questions as a self-administered tool because it is available in many languages. If the patient is illiterate or does not feel like reading the questions, the nurse or health care provider can ask them. Be sure that older men wear their glasses or contact lenses, if needed.

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

• Difficulty in starting (hesitancy) and continuing urination

• Reduced force and size of the urinary stream (“weak” stream)

• Sensation of incomplete bladder emptying

• Straining to begin urination

Prepare the patient for the prostate gland examination. Tell him that he may feel the urge to urinate as the prostate is palpated. Because the prostate is close to the rectal wall, it is easily examined by digital rectal examination (DRE). Help the patient bend over the examination table or assume a side-lying fetal position, whichever is the easiest position for him. The health care provider examines the prostate for size and consistency. BPH presents as a uniform, elastic, nontender enlargement, whereas cancer of the prostate gland feels like a stony-hard nodule. Advise the patient that after the prostate gland is palpated, it may be massaged to obtain a fluid sample for examination to rule out prostatitis (inflammation and possible infection of the prostate), a common problem that can occur with BPH. If the patient has bacterial prostatitis, he is treated with broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy for at least 30 days to prevent the spread of infection (McCance et al., 2010).

Psychosocial Assessment

Post-void dribbling and overflow incontinence may cause embarrassment and prevent the patient from socializing or leaving his home. For some patients, this social isolation can affect quality of life and lead to clinical depression and/or severe anxiety. Johnson et al. (2010) found a strong correlation between depression and BPH in older men. Depressed patients were three times more likely to have severe symptoms.

Laboratory Assessment

Other laboratory studies that may be performed include:

• A complete blood count (CBC) to evaluate any evidence of systemic infection (elevated WBCs) or anemia (decreased red blood cells [RBCs]) from hematuria

• Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine levels to evaluate renal function (both are usually elevated with kidney disease)

• A prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and a serum acid phosphatase level if prostate cancer is suspected (both are typically elevated in patients who have prostate cancer)

• Culture and sensitivity of prostatic fluid (if expressed during the examination)

Other Diagnostic Assessment

In some cases, the physician uses a cystoscope to view the interior of the bladder, the bladder neck, and the urethra. This examination is used to study the presence and effect of bladder neck obstruction. The procedure is usually done in an ambulatory care setting. See Chapter 69 for a detailed description of cystoscopy and the nursing care needed for patients having this procedure.

Planning and Implementation

Improving Urinary Elimination

Interventions

Nonsurgical Management

Drug Alert

Drug Alert

Other drugs may be helpful in managing specific urinary symptoms. For example, low-dose oral desmopressin, a synthetic antidiuretic analog, has been used successfully for nocturia (Wang et al., 2011). Drugs being tested for their effectiveness in treating BPH include bisphosphonates, ezetimibe (Zetia), Botox, and Nymox.

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

Although many men use Serenoa repens (saw palmetto extract), a plant extract, to help manage the urinary symptoms associated with BPH, studies on the effectiveness of this herb have not shown that it is effective (Tackland et al., 2009). Teach patients who want to try these herbs and other natural substances that scientific evidence to prove they are useful is lacking. However, if they choose to take them, remind them to check with their health care provider before taking any OTC natural substance. Some herbs interfere with prescription drugs the patient may be taking for other health problems. Side effects, such as abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, are mild, reversible, and infrequent (Agbabiaka et al., 2009).

Other Nonsurgical Interventions

• Transurethral needle ablation (TUNA) (low radiofrequency energy shrinks the prostate)

• Transurethral microwave therapy (TUMT) (high temperatures heat and destroy excess tissue)

• Interstitial laser coagulation (ILC), also called contact laser prostatectomy (CLP) (laser energy coagulates excess tissue)

• Electrovaporization of the prostate (EVAP) (high-frequency electrical current cuts and vaporizes excess tissue)

Surgical Management

• Acute urinary retention (AUR)

• Chronic urinary tract infections secondary to residual urine in the bladder

When planning surgical interventions, the patient’s general physical condition, the size of the prostate gland, and the man’s preferences are considered. The patient may have many fears and misconceptions about prostate surgery, such as believing that automatic loss of sexual functioning or permanent incontinence will occur. Assess the patient’s anxiety, correct any misconceptions about the surgery, and provide accurate information to him and his family. Regardless of the type of surgery to be performed, provide information about anesthesia (see Chapter 17). The patient may have other medical problems that increase the risk for complications of general anesthesia and may be advised to have regional anesthesia. Epidural and spinal anesthesia are the most common types of anesthesia used for a TURP. Because the patient is awake, it is easier to assess for hyponatremia (low serum sodium), fluid overload, and water intoxication, which can result from large bladder irrigations.

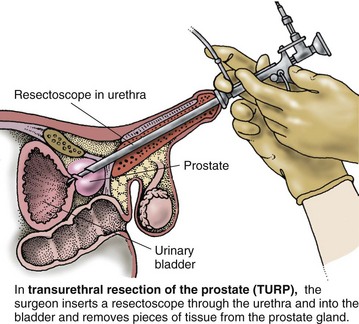

The traditional TURP is a “closed” surgery. To perform the procedure, the surgeon inserts a resectoscope (an instrument similar to a cystoscope, but with a cutting and cauterizing loop) through the urethra (Fig. 75-3). The enlarged portion of the prostate gland is then removed in small pieces (prostate chips). A similar procedure is the transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP), in which small cuts are made into the prostate to relieve pressure on the urethra. This alternate technique is used for smaller prostates. To prevent bleeding and excess clotting, a fibrinolytic inhibitor like tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) may be used during surgery.

In many large medical centers around the world, specialists can perform newer surgical treatments, such as the holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) (Eltabey et al., 2010). For this procedure, the surgeon uses the laser to remove the obstructive prostatic tissue and push it into the bladder for removal and seals all blood vessels. Very little blood is lost during the short procedure and is therefore safe for patients taking anticoagulants.

Remind the patient that because of the urinary catheter’s large diameter and the pressure of the retention balloon on the internal sphincter of the bladder, he will feel the urge to void continuously. This is a normal sensation, not a surgical complication. Advise the patient not to try to void around the catheter, which causes the bladder muscles to contract and may result in painful spasms. Chart 75-1 summarizes the nursing care for patients having a TURP.

Chart 75-1 Best Practice For Patient Safety & Quality Care

Care of the Patient After Transurethral Resection of the Prostate

• Monitor the patient closely for signs of infection. Older men undergoing prostate surgery often also have underlying chronic diseases (e.g., cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, diabetes).

• Help the patient out of the bed to the chair as soon as permitted to prevent complications of immobility. Older men may need assistance because of underlying changes in the musculoskeletal system (e.g., decreased range of motion, stiffness in joints). These patients are at high risk for falls.

• Assess the patient’s pain every 2 to 4 hours, and intervene as needed to control pain.

• Provide a safe environment for the patient. Anticipate a temporary change in mental status for the older patient in the immediate postoperative period as a result of anesthetics and unfamiliar surroundings. Reorient the patient frequently. Keep catheter tubes secure.

• Use normal saline solution for the bladder irrigant unless otherwise prescribed. Normal saline solution is isotonic.

• Monitor the color, consistency, and amount of urine output.

• Check the drainage tubing frequently for external obstructions (e.g., kinks) and internal obstructions (e.g., blood clots, decreased output).

• Assess the patient for reports of severe bladder spasms with decreased urinary output, which may indicate obstruction.

• If the urinary catheter is obstructed, irrigate the catheter per agency or surgeon protocol.

• Notify the physician immediately if the obstruction does not resolve by hand irrigation or if the urinary return becomes ketchup-like.

Critical Rescue

Prostate Cancer

Pathophysiology

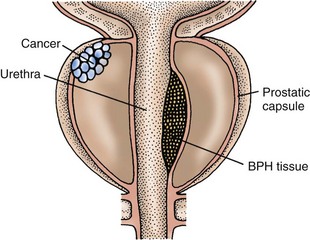

Many prostate tumors are androgen sensitive (McCance et al., 2010). Most are adenocarcinomas and arise from epithelial cells located in the posterior lobe or outer portion of the gland (Fig. 75-4).

Of all malignancies, prostate cancer is one of the slowest growing, and it metastasizes (spreads) in a predictable pattern. Common sites of metastasis are the nearby lymph nodes, bones, lungs, and liver (McCance et al., 2010). The bones of the pelvis, sacrum, and lumbar spine are most often affected. Chapter 23 describes staging categories of localized and advanced cancers.

Prostate cancer is likely caused by a number of factors, including androgens. Dietary factors, such as eating a diet high in animal fat (e.g., red meat) and complex carbohydrates or having a low fiber intake, increase the risk for prostate cancer. Men who have had a vasectomy or those who were exposed to environmental toxins, such as arsenic, may also be at increased risk for the disease (Held-Warmkessel, 2008; McCance et al., 2010).

Genetic/Genomic Considerations

Many gene mutations play a role in various types of prostate cancer. Some men with the most aggressive prostate cancers have BRCA2 mutations similar to those women who have BRCA2-associated breast and ovarian cancers. The most common genetic factor that increases the risk for prostate cancer is a mutation in the glutathione S-transferase (GST P1) gene. This gene is normally part of the pathway that helps prevent cancer (McCance et al., 2010).

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Teach men about the most recent American Cancer Society (ACS) guidelines for prostate cancer screening and early detection (ACS, 2011). The current recommendations are that men should make an informed decision about whether to have prostate cancer screening. Starting at the age of 50, men should discuss the options of having prostate-specific antigen testing with their health care provider. Men at a higher risk for prostate cancer, including African Americans or men who have a first-degree relative with prostate cancer before the age of 65, should have this discussion at age 45. Men who have multiple first-degree relatives with prostate cancer at an early age should discuss screening at age 40.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Psychosocial Assessment

A diagnosis of any type of cancer causes fear and anxiety for most people. Some men, particularly African Americans, develop the disease in their 40s and 50s when they are perhaps planning their retirements, putting their children through college, and/or enjoying their middle years. Assess the reaction of the patient to the diagnosis, and observe how his family reacts to the illness. Men may describe their feelings as shock, fear, anger, and “roller coaster” (Wallace & Storms, 2007). Expect that patients will go through the grieving process and may be in denial or depressed. Determine what support systems they have, such as spiritual leaders or community group support, to help them through diagnosis, treatment, and recovery.

Laboratory Assessment

The normal blood level of PSA in men younger than 50 years is less than 2.5 ng/mL. PSA levels increase to as high as 6.5 ng/mL when men reach their 70s. African-American men have a slighter higher normal value, but the reason for this difference is not known. Because other prostate problems also increase the PSA level, it is not specifically diagnostic for cancer. The level associated with prostate cancer, however, is usually much higher than those occurring with problems such as prostatitis and benign prostatic hyperplasia (Pagana & Pagana, 2010).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree