Chapter 34 Care of Critically Ill Patients with Respiratory Problems

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Protect the patient receiving mechanical ventilation.

2. Ensure safe management of endotracheal tubes, tracheostomy tubes, and mechanical ventilators.

3. Modify the environment to protect patients receiving anticlotting therapy (which includes anticoagulation, fibrinolytic, and antiplatelet therapies).

Health Promotion and Maintenance

4. Identify hospitalized patients at risk for a pulmonary embolism.

5. Teach people at risk for pulmonary embolism techniques to reduce the risk.

6. Teach patients and family members how to avoid injury during anticlotting therapy.

7. Support the patient and family in coping with changes in breathing status and the need for mechanical ventilation.

8. Use an appropriate nonverbal form of communication for a patient who is intubated.

9. Provide emotional support to patients experiencing acute respiratory difficulties.

10. Assess the respiratory status of any patient who develops sudden-onset respiratory difficulty or acute confusion.

11. Use laboratory data and clinical manifestations to evaluate the adequacy of oxygenation and ventilatory interventions.

12. Coordinate nursing care for the patient being mechanically ventilated.

13. Maintain a patent airway on anyone who has experienced chest trauma.

14. Schedule essential patient care and diagnostic activities to promote rest and sleep.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Endotracheal Intubation

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

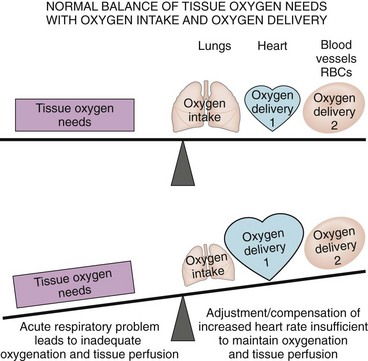

Respiratory problems can progress to an emergency and death, even with prompt treatment. These problems interfere with oxygenation and tissue perfusion and may overwhelm the adaptive responses of the cardiac and blood oxygen delivery systems (Fig. 34-1). Thus prompt recognition and interventions are needed to prevent serious complications and death.

Pulmonary Embolism

Pathophysiology

A pulmonary embolism (PE) is a collection of particulate matter (solids, liquids, or air) that enters venous circulation and lodges in the pulmonary vessels. Large emboli obstruct pulmonary blood flow, leading to reduced oxygenation, pulmonary tissue hypoxia, and potential death. Any substance can cause an embolism, but a blood clot is the most common (McCance et al., 2010). PE is common, especially among hospitalized patients, and many die within 1 hour of the onset of symptoms or before the diagnosis has even been suspected (Farley et al., 2009).

Major risk factors for VTE leading to PE are:

In addition, smoking, pregnancy, estrogen therapy, heart failure, stroke, cancer (particularly lung or prostate), Trousseau’s syndrome, and trauma increase the risk for VTE and PE (Gay, 2010).

Fat, oil, air, tumor cells, amniotic fluid, foreign objects (e.g., broken IV catheters), injected particles, and infected clots or pus can enter a vein and cause PE. Fat emboli from fracture of a long bone and oil emboli from diagnostic procedures do not impede blood flow in the lungs; instead, they cause blood vessel injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Powers & Talbot, 2011). Amniotic fluid embolus occurs in women as a rare complication of childbirth, abortion, or amniocentesis. Septic clots often arise from a pelvic abscess, an infected IV catheter, and injections of illegal drugs. The effects of sepsis are more serious than the venous blockage.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Although pulmonary embolism (PE) can occur in healthy people and may give no warning, it occurs more often in some situations. Thus prevention of conditions that lead to PE is a major nursing concern. Preventive actions for PE are those that also prevent venous stasis and VTE. Best nursing practices for PE prevention are outlined in Chart 34-1. Also see Chapter 16 for more information about core measures for VTE prevention.

Chart 34-1 Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

Prevention of Pulmonary Embolism

• Start passive and active range-of-motion exercises for the extremities of immobilized and postoperative patients.

• Ambulate patients soon after surgery.

• Use antiembolism and pneumatic compression stockings and devices after surgery.

• Avoid the use of tight garters, girdles, and constricting clothing.

• Prevent pressure under the popliteal space (e.g., do not place a pillow under the knee).

• Perform a comprehensive assessment of peripheral circulation.

• Elevate the affected limb 20 degrees or more above the level of the heart to improve venous return, as appropriate.

• Change patient position every 2 hours, or ambulate as tolerated.

• Prevent injury to the vessel lumen by preventing local pressure, trauma, infection, or sepsis.

• Refrain from massaging leg muscles.

• Instruct patient not to cross legs.

• Administer prescribed prophylactic low-dose anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs.

• Teach the patient to avoid activities that result in the Valsalva maneuver (e.g., breath-holding, bearing down for bowel movements, coughing).

• Administer prescribed drugs, such as stool softeners, that will prevent episodes of the Valsalva maneuver.

• Teach the patient and family about precautions.

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Respiratory manifestations are outlined in Chart 34-2. Assess the patient for difficulty breathing (dyspnea) occurring with a rapid heart rate and pleuritic chest pain (sharp, stabbing-type pain on inspiration). Other symptoms vary depending on the size and the type of embolism. Breath sounds may be normal, but crackles usually occur. Often a dry cough is present. Hemoptysis (bloody sputum) may result from pulmonary infarction.

Critical Rescue

Miscellaneous manifestations include a low-grade fever and petechiae on the skin over the chest and in the axillae. It is important to remember that many patients with PE do not have the “classic” manifestations but instead have vague symptoms resembling the flu, such as nausea, vomiting, and general malaise (Bahloul et al., 2010).

Laboratory Assessment

The hyperventilation triggered by hypoxia and pain first leads to respiratory alkalosis, indicated by low partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) values on arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis. The PaO2-FiO2 (fraction of inspired oxygen) ratio falls as a result of “shunting” of blood from the right side of the heart to the left without picking up oxygen from the lungs. Shunting causes the PaCO2 level to rise, resulting in respiratory acidosis (McCance et al., 2010). Later, metabolic acidosis results from buildup of lactic acid due to tissue hypoxia. (See Chapter 14 for a discussion.)

Even if ABG studies and pulse oximetry show hypoxemia, these results alone are not sufficient for the diagnosis of PE (Bahloul et al., 2010; McCance et al., 2010).A patient with a small embolus may not be hypoxemic, and PE is not the only cause of hypoxemia.

Imaging Assessment

The physician may perform a transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) (see Chapter 35) to help detect PE. Doppler ultrasound studies or impedance plethysmography (IPG) may be used to document the presence of VTE and to support a diagnosis of PE.

Patient-Centered Care; Safety; Evidence-Based Practice

Planning and Implementation

Managing Hypoxemia

Interventions.

Nonsurgical management of PE is most common. In some cases, surgery also may be needed. Best nursing care practices for the patient with PE are listed in Chart 34-3.

Chart 34-3 Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

Care of the Patient with a Pulmonary Embolism

• Reassure patient that the correct measures are being taken.

• Apply oxygen by nasal cannula or mask.

• Place patient in high-Fowler’s position.

• Apply telemetry monitoring equipment.

• Obtain an adequate venous access.

• Assess oxygenation continuously with pulse oximetry.

• Assess respiratory status at least every 30 minutes by:

• Ensure prescribed chest imaging and laboratory tests are obtained immediately (may include complete blood count with differential, platelet count, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, D-dimer level, arterial blood gases).

• Examine the thorax for presence of petechiae.

• Administer prescribed anticoagulants.

Nonsurgical Management.

Drug Alert

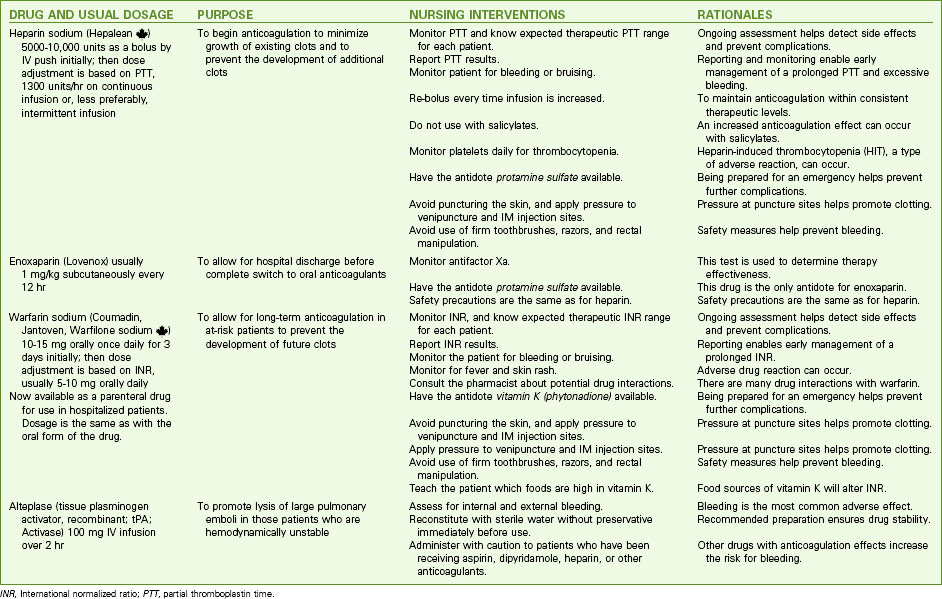

Heparin therapy usually continues for 5 to 10 days. Most patients are started on an oral anticoagulant, such as warfarin (Coumadin, Jantoven, Warfilone ![]() ), on the third day of heparin use. Therapy with both heparin and warfarin continues until the international normalized ratio (INR) reaches 2.0 to 3.0. A low–molecular-weight heparin (e.g., dalteparin or enoxaparin) is often used with the warfarin. Monitor the INR daily. Warfarin use continues for 3 to 6 weeks, but some patients may take warfarin indefinitely. Charts 34-4 and 34-5 list common drugs used and the laboratory tests to monitor. These drugs and the associated nursing care are discussed in Chapters 38, 40, and 41.

), on the third day of heparin use. Therapy with both heparin and warfarin continues until the international normalized ratio (INR) reaches 2.0 to 3.0. A low–molecular-weight heparin (e.g., dalteparin or enoxaparin) is often used with the warfarin. Monitor the INR daily. Warfarin use continues for 3 to 6 weeks, but some patients may take warfarin indefinitely. Charts 34-4 and 34-5 list common drugs used and the laboratory tests to monitor. These drugs and the associated nursing care are discussed in Chapters 38, 40, and 41.

Chart 34-4 Common Examples of Drug Therapy

Pulmonary Embolism

INR, International normalized ratio; PTT, partial thromboplastin time.

Blood Tests Used to Monitor Anticoagulation Therapy

Physiological Integrity

Surgical Management.

Two surgical procedures for the management of PE are embolectomy and inferior vena cava filtration.

Embolectomy is the surgical removal of the embolus from pulmonary blood vessels. It may be performed when fibrinolytic therapy cannot be used for a patient who has massive or multiple large pulmonary emboli with shock. Special thrombectomy catheters that mechanically break up clots, such as the AngioJet, allow effective reduction of clots with or without the use of thrombolytic drugs. Earlier use of embolectomy for PE is being evaluated (Le & Dewan, 2009).

Inferior vena cava filtration with placement of a vena cava filter is a lifesaving measure by preventing further embolus formation for some patients. Some filters are removable, allowing filter placement before symptoms develop in patients who are at high risk for clots. These filters can be removed when the risk for clot formation decreases, or they can be left in place permanently. Patients for whom filter placement is considered less risky than drug therapy include those with recurrent or major bleeding while receiving anticoagulants, those with septic PE, and those undergoing pulmonary embolectomy. Placement of a vena cava filter is detailed in Chapter 38.

Managing Hypotension

Interventions.

IV fluid therapy involves giving crystalloid solutions to restore plasma volume and prevent shock (see Chapter 39). Continuously monitor the ECG and pulmonary artery and central venous/right atrial pressures of the patient receiving IV fluids because increased fluids can worsen pulmonary hypertension and lead to right-sided heart failure. Also monitor indicators of fluid adequacy, including urine output, skin turgor, and moisture of mucous membranes.

Minimizing Bleeding

Planning: Expected Outcomes.

The patient with PE is expected to remain free from bleeding. Indicators are:

Interventions.

Assess at least every 2 hours for evidence of bleeding (e.g., oozing, bruises that cluster, petechiae, or purpura). Examine all stools, urine, drainage, and vomitus for gross blood, and test for occult blood. Measure any blood loss as accurately as possible. Measure the patient’s abdominal girth every 8 hours (increasing girth can indicate internal bleeding). Best practices to prevent bleeding are listed in Chart 34-6.

Chart 34-6 Best Practice for Patient Safety & Quality Care

Prevention of Injury for the Patient Receiving Anticoagulant, Fibrinolytic, or Antiplatelet Therapy

• Use and teach UAP to use a lift sheet when moving and positioning the patient in bed.

• Avoid IM injections and venipunctures.

• When injections or venipunctures are necessary, use the smallest-gauge needle for the task.

• Apply firm pressure to the needle stick site for 10 minutes or until the site no longer oozes blood.

• Apply ice to areas of trauma.

• Test all urine, vomitus, and stool for occult blood.

• Observe IV sites every 4 hours for bleeding.

• Instruct alert patients to notify nursing personnel immediately if any trauma occurs and if bleeding or bruising is noticed.

• Avoid trauma to rectal tissues:

• Instruct the patient and UAP to use an electric shaver rather than a razor.

• When providing mouth care or supervising others in providing mouth care:

• Instruct the patient not to blow the nose forcefully or insert objects into the nose.

• Ensure the patient wears shoes with firm soles whenever he or she is ambulating.

• Ensure that antidotes to anticoagulation therapy are on the unit.

Monitor laboratory values daily. Review the complete blood count (CBC) results to determine the risk for bleeding and whether actual blood loss has occurred. If the patient has severe blood loss, packed red blood cells may be prescribed (see Transfusion Therapy in Chapter 42). Monitor the platelet count. A decreasing count may indicate ongoing clotting or heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) caused by the formation of anti-heparin antibodies.

Minimizing Anxiety

Interventions.

The patient with PE is anxious and fearful for many reasons, including the presence of pain. Interventions for reducing anxiety in those with PE include oxygen therapy (see Interventions discussion on pp. 664-667 in the Managing Hypoxemia section), communication, and drug therapy.

Safe and Effective Care Environment

A. Administer the medications as prescribed.

B. Remind the prescriber that two anticoagulants should not be administered concurrently.

C. Hold the dose of warfarin until the client’s partial thromboplastin time is the same as the control value.

D. Monitor the client for clinical manifestations of internal or external bleeding at least every 2 hours.

Community-Based Care

Teaching for Self-Management

The patient with a PE may continue anticoagulation therapy for weeks, months, or years after discharge, depending on the risks for PE. Teach him or her and the family about Bleeding Precautions, activities to reduce the risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) and recurrence of PE, complications, and the need for follow-up care (Chart 34-7).

Chart 34-7 Patient and Family Education

preparing for self-management: Preventing Injury and Bleeding

During the time you are taking anticoagulants:

Health Care Resources

Patients using anticoagulation therapy are usually seen in a clinic or health care provider’s office weekly for blood drawing and assessment. Those who are homebound may have a home care nurse perform these actions (see Chart 34-8 for a focused assessment guide). Patients with severe dyspnea may need home oxygen therapy. Respiratory therapy treatments can be performed in the home. The nurse or case manager coordinates arrangements for oxygen and other respiratory therapy equipment to be available if needed at home.

Chart 34-8 Home Care Assessment

The Patient After Pulmonary Embolism

Assess lower extremities for deep vein thrombosis:

Assess for evidence of bleeding:

Assess cognition and mental status:

Assess the patient’s understanding of illness and adherence to treatment:

Acute Respiratory Failure

Pathophysiology

Ventilatory Failure

Causes of ventitatory failure are either extrapulmonary (involving nonpulmonary tissues but affecting respiratory function) or intrapulmonary (disorders of the respiratory tract). Table 34-1 lists causes of ventilatory failure.

TABLE 34-1 COMMON CAUSES OF VENTILATORY FAILURE

| Extrapulmonary Causes | Intrapulmonary Causes |

• Spinal cord injuries affecting nerves to intercostal muscles • Central nervous system dysfunction: < div class='tao-gold-member'> Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

) mismatch in which perfusion is normal but ventilation is inadequate. It occurs when the chest pressure does not change enough to permit air movement into and out of the lungs. As a result, too little oxygen reaches the alveoli and carbon dioxide is retained. Either inadequate oxygen intake or carbon dioxide retention leads to hypoxemia.

) mismatch in which perfusion is normal but ventilation is inadequate. It occurs when the chest pressure does not change enough to permit air movement into and out of the lungs. As a result, too little oxygen reaches the alveoli and carbon dioxide is retained. Either inadequate oxygen intake or carbon dioxide retention leads to hypoxemia.