Chapter 47 Care of Critically Ill Patients with Neurologic Problems

Safe and Effective Care Environment

1. Explain the importance of collaborating with health care team members when planning and providing care for critically ill patients with neurologic problems.

2. Prioritize care for patients with a stroke or traumatic brain injury (TBI).

3. Identify community resources for patients with severe neurologic problems and their families.

4. Discuss the importance of maintaining continuous care between the hospital and community-based agencies for patients discharged with a stroke, head injury, or brain tumor.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

5. Develop a teaching plan about risk factors for having a stroke.

6. Describe how to perform a comprehensive neurologic assessment of patients who have a stroke.

7. Identify the need to assess the family’s response to a brain cancer diagnosis and treatment options.

8. Discuss how to support the patient and family coping with life changes that often result from a TBI or stroke.

9. Assess the needs of patients with stroke who have altered sensory perception.

10. Differentiate clinical manifestations and management of patients with a transient ischemic attack (TIA) and stroke.

11. Perform a focused neurologic assessment of patients who are critically ill.

12. Assess the patient on fibrinolytic therapy for potential adverse effects.

13. Develop and evaluate an evidence-based plan of care for the patient with a stroke.

14. Assess patients for adverse responses to TBI, such as increased intracranial pressure (ICP).

15. Develop a plan of care for interventions to prevent increasing ICP.

16. Manage care for the patient experiencing increased ICP.

17. Develop a postoperative plan of care for the patient having a craniotomy.

18. Prevent and monitor for postoperative complications of a craniotomy.

19. Explain the role of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery in the management of patients with brain tumors.

20. Explain the primary focus for management of patients with a brain abscess.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Transient Ischemic Attack and Reversible Ischemic Neurologic Deficit

Ischemic strokes often follow warning signs such as a transient ischemic attack (TIA) (also called a silent stroke) or a reversible ischemic neurologic deficit (RIND) (Chart 47-1). Both warning signs cause temporary neurologic dysfunction resulting from a brief interruption in cerebral blood flow, possibly due to cerebral vasospasm or systemic arterial hypertension. The difference between a TIA and a RIND is the length of time the patient is symptomatic. A TIA lasts a few minutes to fewer than 24 hours, whereas RIND symptoms last longer than 24 hours but less than a week. Typically, symptoms of a TIA resolve within 30 to 60 minutes. It is not unusual for symptoms to resolve by the time the patient reaches the emergency department (ED). Both TIAs and RINDs may damage the brain tissue with repeated insults, as seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). Multiple TIAs indicate a high stroke risk.

Transient Ischemic Attack

| Visual Deficits |

| Motor Deficits |

| Sensory Deficits |

| Speech Deficits |

Upon admission to the ED, the patient is stabilized as necessary. A complete neurologic assessment is performed, and routine laboratory work, electrocardiogram, and CT scan are done. Patients older than 65 years and those with diabetes, symptoms lasting longer than 10 minutes, or motor or speech difficulties often are admitted. At discharge, the patient is usually placed on anticoagulant therapy (e.g., clopidogrel [Plavix]) unless medically contraindicated. As part of the discharge processes, ensure that the patient is aware of bleeding precautions and the actions to take should bleeding occur. Anticoagulant therapy is discussed in detail in Chapter 38 in the Venous Thromboembolism section. Reinforce the need to follow up with the health care provider and to complete any diagnostic tests requested on an ambulatory care basis.

Stroke (Brain Attack)

Pathophysiology

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the United States and is considered a major disability worldwide. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 136,000 Americans die each year from stroke (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011).

Types of Strokes

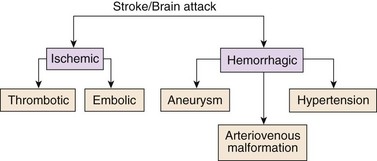

Strokes are generally classified as ischemic (occlusive) or hemorrhagic (Fig. 47-1). Acute ischemic strokes are either thrombotic or embolic in origin (Table 47-1). Most strokes are ischemic.

Ischemic Stroke

Thrombotic Stroke

Thrombotic strokes account for more than half of all strokes and are commonly associated with the development of atherosclerosis in either intracranial or extracranial arteries (usually the carotid arteries). Atherosclerosis is the process by which fatty plaques develop on the inner wall of the affected arterial vessel. Chapter 38 describes this health problem, including its pathophysiology, in more detail.

Hemorrhagic Stroke

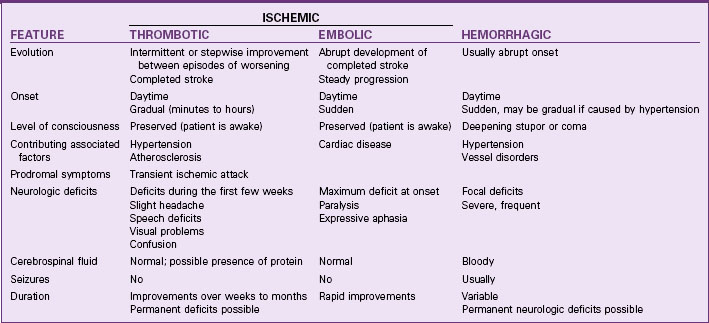

Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is much more common and results from bleeding into the subarachnoid space, the space between the pia mater and arachnoid layers of the meninges covering the brain. This type of bleeding is usually caused by a ruptured aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation (Mink & Miller, 2011b).

An arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is an uncommon abnormality that occurs during embryonic development. It is a tangled or spaghetti-like mass of malformed, thin-walled, dilated vessels (Fig. 47-2). The congenital absence of a capillary network forms an abnormal communication between the arterial and venous systems. The vessels may eventually rupture, causing bleeding into the subarachnoid space or into the intracerebral tissue, because normally the capillary network lowers the pressure between the arterial and venous systems. In the absence of the capillary network, the thin-walled veins are subjected to arterial pressure.

Health Promotion and Maintenance

People with predisposing health conditions should be aware that they could have a stroke unless they change their lifestyle habits (Chart 47-2). Teach them the importance of seeking professional health care and adhering to the recommended treatment plan. Also remind them that other risk factors contribute to health problems such a sedentary lifestyle and high-fat diet. Recommend a diet high in fruits and vegetables and low in saturated and trans fats. Light to moderate alcohol consumption may reduce the risk for stroke, but a higher consumption may increase it. Additional information about lifestyle modifications, such as weight control and smoking cessation, can be found elsewhere in this text. Table 47-2 lists common risk factors that cannot be changed (nonmodifiable) and those that may be altered with appropriate care management.

Chart 47-2 Patient and Family Education

Preparing For Self-Management: Common Modifiable Risk Factors for Developing a Stroke

TABLE 47-2 RISK FACTORS FOR DEVELOPING STROKE THAT CANNOT BE CHANGED OR CAN BE ALTERED WITH COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT

American Indian/Alaskan Native groups have the highest prevalence of stroke. Black men and women have more strokes than white men and women. Hispanic or Latino men have more strokes than non-Hispanic men (Summers et al., 2009). Mexican Americans with atrial fibrillation have more recurrent strokes than non-Hispanic whites (see the Evidence-Based Practice box on p. 1008). The causes for these differences are not well known, but genetic, environmental, and/or lifestyle factors may play a role, including dietary habits.

Are Some Ethnic Groups More Likely to Have Recurrent Strokes Than Others?

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Patient-Centered Collaborative Care

Assessment

Physical Assessment/Clinical Manifestations

Critical Rescue

ED nurses perform a complete neurologic assessment on admission. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is a commonly used valid and reliable assessment tool that nurses complete as soon as possible after the patient arrives in the ED (Table 47-3). The NIHSS includes 11 areas of assessment and serves as the patient’s baseline (Mink & Miller, 2011a). The most important area to assess is the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC). Use the Glasgow Coma Scale (see Fig. 43-10 in Chapter 43 on p. 918) to frequently monitor for changes in LOC that could indicate increased intracranial pressure. Specific patient manifestations depend on the extent and location of the ischemia and the arteries involved (Chart 47-3).

* The patient can have a score of 0 to 40, with 0 having no neurologic deficits and 40 being the most deficits.

Modified from National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, 2003. www.ninds.nih.gov/doctors/NIH_stroke_scale.pdf.

Stroke Syndromes

| Middle Cerebral Artery Strokes |

| Posterior Cerebral Artery Strokes |

| Internal Carotid Artery Strokes |

| Anterior Cerebral Artery Strokes |

| Vertebrobasilar Artery Strokes |

Cognitive Changes

• Spatial and proprioceptive (awareness of body position in space) dysfunction

• Impairment of memory, judgment, or problem-solving and decision-making abilities

Dysfunction in one or more of these areas may be severe depending on the hemisphere involved (Chart 47-4).

*Location for speech in all but 15% to 20% of people.

Key Features

Left and Right Hemisphere Strokes

| FEATURE | LEFT HEMISPHERE* | RIGHT HEMISPHERE |

|---|---|---|

| Language | Impaired sense of humor | |

| Memory | Possible deficit | |

| Vision | ||

| Behavior | ||

| Hearing | No deficit | Loss of ability to hear tonal variations |

Sensory Changes

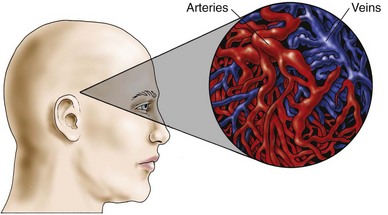

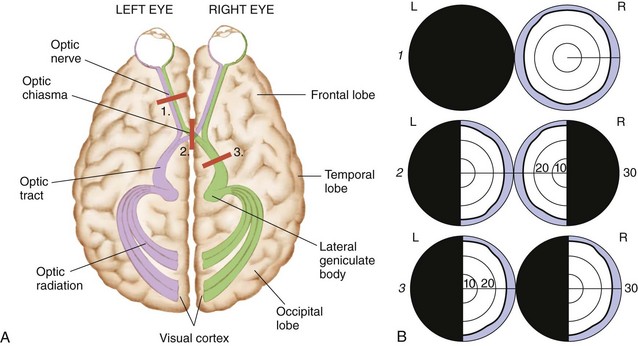

Another important part of the nursing assessment focuses on visual ability. Infarction or ischemia involving the carotid artery may cause pupil constriction or dilation, ptosis (eyelid drooping), visual field deficits, or pallor and petechiae of the conjunctiva. Amaurosis fugax, a brief episode of blindness in one eye, results from retinal ischemia caused by ophthalmic or carotid artery insufficiency. Hemianopsia, or blindness in half of the visual field, results from damage to the optic tract or occipital lobe. Usually this deficit occurs as homonymous hemianopsia, in which there is blindness in the same side of both eyes (Fig. 47-3). The patient with this condition must turn his or her head to scan the complete range of vision. Otherwise, he or she does not see half of the visual field. For example, the patient eats only half of a meal because that is the only portion seen. Patients with brainstem or cerebellar damage may have abnormal eye movements, such as nystagmus (involuntary movements of the eyes).

Imaging Assessment

Brain imaging is the most important tool for confirming the diagnosis of a stroke. Computed tomography (CT) without contrast is the standard for initial diagnosis (Mink & Miller, 2011b). Cerebral aneurysms, if large enough, may also be identified. For a patient with an ischemic or occlusive stroke, the head CT is usually initially negative, indicating thrombotic or embolic stroke rather than intracerebral hemorrhage. After the first 24 hours, CT shows progressive changes of ischemia, infarction, and associated cerebral edema. This test is invaluable in establishing baseline information for future comparison in case the patient’s condition deteriorates. In addition, the scan enables the physician to identify pathologic changes that may mimic a stroke, such as a brain tumor or cerebral hematoma, both of which may be unrelated to cerebrovascular disease.

Analysis

The priority problems for patients with a stroke are:

1. Inadequate perfusion to the brain related to interruption of arterial blood flow and a possible increase in ICP

2. Impaired Swallowing related to neuromuscular impairment

3. Impaired Physical Mobility and Self-Care Deficit related to neuromuscular impairment or cognitive impairment

4. Aphasia or dysarthria related to decreased circulation in the brain or facial muscle weakness

5. Urinary and/or Bowel Incontinence related to reflex bladder and bowel

6. Sensory changes related to altered neurologic reception, transmission, and perception

7. Unilateral body neglect syndrome related to disturbed perceptual abilities or hemianopsia

Planning and Implementation

Improving Cerebral Perfusion

Interventions

Interventions for patients experiencing strokes are determined primarily by the type and extent of the stroke. For patients having ischemic strokes, the standard of practice is to start two IV lines with non-dextrose isotonic saline (Summers et al., 2009). The immediate primary role of the nurse is to manage the patient receiving treatment and continuously assess for increasing intracranial pressure.

Nonsurgical Management

Fibrinolytic Therapy

For select patients with ischemic strokes, early intervention with fibrinolytic therapy (“clot-busting drug”) is the standard of practice to improve blood flow to or through the brain. The success of fibrinolytic therapy from a stroke depends on the interval between the time the patient was last seen normal (LSN) and available treatment. It also depends on where the treatment is given. Hospitals with stroke centers or specialized stroke teams who care for numerous stroke patients have lower mortality rates than those hospitals that care for fewer of these patients (Bederson et al., 2009).

• Anticoagulation with an international normalized ratio less than or equal to 1.7

• Baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale greater than 25

Women typically have 30% lower odds of receiving tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) than men. These disparities are very concerning because tPA is the only approved therapy to reduce the functional limitations caused by ischemic stroke and there is evidence that women have better outcomes from tPA than men. The reasons for lower tPA rates in women are not yet fully understood. Advocate for women by teaching them about this finding, and discuss the importance of coming to the ED in a timely fashion as soon as stroke symptoms begin (Beal, 2010).

Drug Alert

In addition to frequent monitoring of vital signs, carefully observe for signs of intracerebral hemorrhage and other signs of bleeding during administration of rtPA. Other best practice interventions are listed in Chart 47-5.

Chart 47-5 Best Practice For Patient Safety & Quality Care

Nursing Interventions During and After IV Administration of rtPA

• Infuse 0.9 mg/kg (maximum dose 90 mg) over 60 minutes with 10% of the dose given as a bolus over 1 minute.

• Admit the patient to a critical care or specialized stroke unit.

• Perform neurologic assessments, including vital signs, every 10 to 15 minutes during infusion and every 30 minutes after that for at least 6 hours; monitor hourly for 24 hours after treatment.

• If systolic blood pressure is 180 mm Hg or greater or diastolic is 105 mm Hg or greater, give antihypertensive drugs as prescribed.

• Do not place invasive tubes, such as NG tubes or indwelling urinary catheters, until patient is stable to prevent bleeding.

• Discontinue the infusion if the patient reports severe headache or has severe hypertension, bleeding, nausea, and/or vomiting; notify the health care provider immediately.

• Obtain a follow-up CT scan after treatment before starting antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs.

Physiological Integrity

Endovascular Interventions

Endovascular procedures include intra-arterial thrombolysis using drug therapy and mechanical embolectomy (clot removal). Intra-arterial thrombolysis has the advantage of delivering the fibrinolytic agent directly into the thrombus within 6 hours of the stroke’s onset. It is particularly beneficial for some patients who have an occlusion of the middle cerebral artery or those who arrive in the ED after the window for rtPA. If the patient arrives in less than 8 hours, the interventional neuroradiologist may perform mechanical embolectomy using special instrumentation systems that can remove the clot by suction or other method (Mink & Miller, 2011a). Patients having either fibrinolytic therapy or endovascular interventions are admitted to the critical care setting for intensive collaborative monitoring.

Some patients may have worsening of their neurologic status starting within 24 to 48 hours after their stroke. A major complication is increased intracranial pressure (ICP) (Chart 47-6). Reassess patients every 1 to 4 hours (depending on severity of the condition) using the approved assessment tools.

Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP)

• Decreased level of consciousness (LOC) (lethargy to coma)

• Behavior changes: restlessness, irritability, and confusion

• Nausea and vomiting (may be projectile)

• Change in sensorimotor status

• Pupillary changes: dilated and nonreactive pupils (“blown pupils”) or constricted and nonreactive pupils

• Seizures (usually within first 24 hrs after stroke)

Monitoring for Increased Intracranial Pressure

Critical Rescue

Keep the head of the bed (HOB) elevated to between 25 and 30 degrees to prevent a decreased blood flow to the brain. The best HOB positioning has not yet been determined, and more studies are needed to determine best practice. Provide oxygen therapy to prevent hypoxia for patients with oxygen saturation less than 92% or those with a decreased LOC (Summers et al., 2009). Maintain the head in a midline, neutral position to help promote venous drainage from the brain. When severe hemiparesis is present, position the patient on his or her side to prevent aspiration and promote comfort.

Evidence-based guidelines are not available for managing blood pressure in patients with hemorrhagic strokes, but for many patients, severe hypertension is the cause of their stroke (Mink & Miller, 2011b).

Critical Rescue

Ongoing Drug Therapy

Although previously widely used, anticoagulants are controversial and are not considered current best practice by the American Stroke Association for acute ischemic strokes or for preventing future strokes (Adams et al., 2007). Sodium heparin and other anticoagulants, such as warfarin (Coumadin, Warfilone ![]() ), are high-alert drugs that can cause bleeding, including intracerebral hemorrhage.

), are high-alert drugs that can cause bleeding, including intracerebral hemorrhage.

However, an initial dose of 325 mg of enteric-coated or other form of aspirin (Ecotrin, Ancasal ![]() ) is recommended within 24 to 48 hours after stroke onset. Aspirin should not be given within 24 hours of rtPA administration. These drugs are antiplatelet drugs and prevent blood clotting by reducing platelet adhesiveness (clumping). They can cause bruising, hemorrhage, and liver disease over a long-term period. Teach the patient to report any unusual bruising or bleeding to the health care provider. The 2007 best practice guidelines for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke recommend against the use of clopidogrel (Plavix) alone or in combination with aspirin (Adams et al., 2007). However, many health care providers still prescribe them.

) is recommended within 24 to 48 hours after stroke onset. Aspirin should not be given within 24 hours of rtPA administration. These drugs are antiplatelet drugs and prevent blood clotting by reducing platelet adhesiveness (clumping). They can cause bruising, hemorrhage, and liver disease over a long-term period. Teach the patient to report any unusual bruising or bleeding to the health care provider. The 2007 best practice guidelines for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke recommend against the use of clopidogrel (Plavix) alone or in combination with aspirin (Adams et al., 2007). However, many health care providers still prescribe them.

To treat seizures, lorazepam (Ativan), a benzodiazepine, may be administered with close neurologic and cardiopulmonary monitoring. For long-term antiseizure therapy, the health care provider may also prescribe antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), such as phenytoin (Dilantin), gabapentin (Neurontin), or topiramate (Topamax). Neuroprotective drugs such as calcium channel blockers (e.g., nimodipine [Nimotop]) may be given to treat or prevent cerebral vasospasm after a subarachnoid hemorrhage. Vasospasm, which usually occurs between 4 and 14 days after the stroke, slows blood flow to the area and worsens ischemia. Calcium channel blockers work by relaxing the smooth muscles of the vessel wall and reducing the incidence and severity of the spasm. Neurologic functioning may improve, and further deterioration from ischemia is then prevented. In addition, these drugs dilate collateral vessels to ischemic areas of the brain. Although these neuroprotective and vasodilating drugs are sometimes used, the American Stroke Association does not recommend them (Adams et al., 2007). Stool softeners, analgesics for pain, and antianxiety drugs may also be prescribed as needed for symptom management. Stool softeners also prevent the Valsalva maneuver during defecation to prevent increased ICP.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree