CHAPTER 32 Care and rehabilitation of people with long-term conditions

What is a long-term condition?

Although capturing their complexity is difficult, a number of attempts have been made to describe both congenital and acquired conditions that are ‘long term and have a profound influence on the lives of sufferers’ (Locker 2008). Although the terms ‘long-term condition’, ‘life-long condition’, ‘chronic disease and ‘chronic illness’ are often used interchangeably, the way these are applied reveals assumptions about enduring conditions and the individuals who experience them. For example, the seminal North American definition proposed by the Commission on Chronic Illness in the 1950s (cited by Daly 1993) focuses on pathology and identifies chronic illness as being a deviation from the norm. This raises questions as to what constitutes a ‘normal’ state, as well as suggesting that people with such conditions are ‘less than normal’. More recently, Larsen (2009) offered Curtin & Lubkin’s (1995) definition to contend that from a nursing perspective: ‘Chronic illness is the irreversible presence, accumulation, or latency of disease states or impairments that involve the total human environment for supportive care and self-care, maintenance of function, and prevention of further disability’. This reflects growing interest in person-centredness and attending to the totality of individual circumstances.

Does it matter what we call it?

Models of disability

Models of disability are often represented as opposing medical and social models. The medical model regards disability as a problem which is intrinsic to the person and caused directly by disease, a health condition or trauma. Here, ‘impairment’ is not only used to describe disturbance in the body’s structure and function. It is also seen as responsible for preventing the individual’s participation in normal society and, therefore, disabling them. This means that management of disability is diagnosis-related and cure-oriented, led by professionals, and aims either to improve the individual’s functional ability to engage in society according to its norms or to make separate (segregated) provision for them. Conversely, the social model is based on the assumption that disability exists where attitudinal or environmental barriers exclude people with impairments from full engagement in mainstream activities. This defines it as a socially created problem which is distinct from and superimposed on impairment. From this standpoint disability can be managed collectively by social action. This seeks to remove and change barriers, whether present though society’s intent or omission, and to support individuals in dealing with them (WHO 2001).

There is a danger of seeing the above models as absolutes, for example in judging services simplistically as either focusing on medical intervention or not. The social model arose from the British disability movement and, in characterising disabled people as an oppressed group, has been central to its civil rights agenda. As Shakespeare & Watson (2002) comment, however: ‘Most activists concede that behind closed doors they talk about aches and pains and urinary tract infections, even while they deny any relevance of the body while they are out campaigning’.

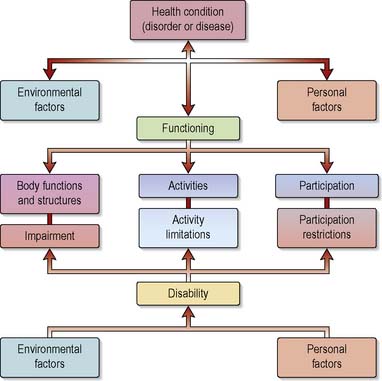

The WHO’s (2001) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) was developed with the intent of synthesising the above models via a bio-psychosocial approach. Its aims included establishing a common language to improve communication between service stakeholders and a framework that would allow international comparison. In so doing, it provides a conceptual basis for defining, measuring and formulating policy for health and disability. Using this gives nurses the potential to understand disability’s social, political and cultural dimensions and provides a platform for working collaboratively with disabled people and other health professionals (Kearney & Pryor 2004).

The ICF (WHO 2001) comprises two parts, each being made up of two components. Part One is concerned with functioning and disability, encompassing body structures and functions, activities and participation; Part Two addresses contextual environmental and personal factors. As shown (Figure 32.1), these elements have an interactive and dynamic relationship.

This work supersedes the International Classification of Impairments, Disability and Handicaps (ICIDH) (WHO 1980). The term ‘handicap’ was then used to describe comparative disadvantage and role loss but is now perceived as pejorative and generally avoided. In North America, however, the term is used in the same way as ‘disabled’ is in Britain (e.g. designation of handicap parking spaces).

Disabled people are divided over the use of other collective descriptors of themselves. For example, some choose to use the term ‘crip’, reclaiming the term ‘cripple’ in their identity, whereas others feel it offensive. Importantly, being referred to in this way by non-disabled people and without permission is regarded as offensive. Similarly, some disabled people draw distinctions between themselves and those without disability by referring to them as ‘AB/AM’ (able-bodied/able-minded) or ‘normie’ (Box 32.1).

Social perceptions of long-term conditions and disability

Lifestyle and blame

Clear associations can be made between aspects of lifestyle and some long-term conditions; for example, smoking is linked with lung cancer, and a diet high in saturated fats with coronary heart disease. Awareness of such relationships might result in individuals being judged to have caused their own disease and suffering. There is also an implication that they have failed to respond to preventive health education campaigns. Attribution of blame has a strong moral influence where links can be alleged between diseases and sexual behaviour, such as that between HIV/AIDS and promiscuity. Beliefs concerning the origin of long-term conditions and disability appear, therefore, to reflect a combination of moral ideology and scientific principles (Box 32.2).

Disability and unemployment

In an industrialised society, however, technological developments and diversification of working practices should create opportunities for those with a wide range of disabilities to gain employment. Nonetheless, disabled people encounter discrimination. One in five people of working age can be defined as disabled, yet 52.6% of disabled people are unemployed and they are three times more likely to be economically inactive than other groups. UK legislation has not fully addressed this because the Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) 1995 and its subsequent amendment (2005) are subject to interpretation while the impact of the Equality Act (2010) remains to be seen. For example, this now prevents employers asking about an applicant’s health before offering them work but does allow them to ask questions regarding assessment and need for reasonable adjustment. Also the onus is on individuals to demonstrate that they are disabled under the terms of the Act and assert their rights. Decline in employment rates for disabled people since introduction of the Act could be due to employers’ lack of awareness and perceived added costs of recruiting or retaining disabled staff (Bambra & Pope 2007). Thus applicants for posts that match their skills and experience might still not be short-listed, with reasons other than disability used to explain why their profile is not considered appropriate. Some issues around employment will be explored later in this chapter.

Work and the state benefit system

Despite evidence that many economically inactive people with long-term conditions want to work (Disability Rights Commission 2006), some believe instead that they are malingerers who choose not to (Scambler 2008). When this view predominates, programmes for the alleviation of poverty concentrate on reforming attitudes, promoting simplistic models of condition management, implementing workfare-style schemes and subjecting individuals whose impairments are well established to repeated, rigorous testing to ‘prove’ incapacity (Ravetz 2006). Accessing state benefits is further complicated by their administration, range, difficulty in obtaining definitive information and varying criteria for eligibility. Media representations of the benefits culture and fraudulent claims can leave people with long-term conditions feeling that they are perceived as ‘spongers’, yet entitlement to some payments assumes an all-or-nothing approach to fitness for work and limits the hours and the time recipients can engage in ‘permitted work’ without losing their entitlement. This traps individuals into remaining on benefits because it prevents them from testing their capabilities, gaining confidence and accumulating experience to assist in obtaining paid employment.

Stigma

According to Goffman’s (1963) seminal text, the word ‘stigma’ was originally used with reference to visible signs inflicted to brand individuals (including slaves or criminals) unfit for participation in normal social interaction. These signs had moral and judgemental implications, such that the disgrace and shame of the stigma assumed more importance than its physical presence. The stigma attached to a long-term condition relates to deviation from the perceived norm and depends on the body part involved, visibility, controlability and diagnostic labelling. Dependency can also be stigmatising. Reliance on services, state benefits or other people means that individuals with long-term conditions are in a position of receiving without being able to contribute in return. To be labelled with a long-term condition is to be deemed exceptional and, in many cases, marginalised. People in this situation engage in constant efforts to make themselves acceptable and their stigmatising condition often dominates their social identity and relations with others (Box 32.3).

People with less visible conditions such as epilepsy experience ‘felt stigma’ which increases the stress of managing their condition (Jacoby et al 2005). The problem of constantly concealing part of oneself in order to pass as normal and avoid being found out is added to by difficulties in gauging which details to share with whom, so that relationships can be maintained. Relatives also experience stigma by association and this affects their relationship with the individual and wider society. Cultural and ethnic dimensions also have relevance here, as illustrated by Chadha’s (2003) experience of living with multiple sclerosis (MS). Because this is seen by the UK’s Asian community as a disorder more likely to be found in the indigenous white population, it left him isolated, misunderstood and ‘made to feel that my immediate family and I were responsible’.

Health care workers share society’s view of disability. Reflecting this in their interactions with disabled people can compromise effective care (Seccombe 2007). Perceiving disabled people to be dependent or to be pitied gives rise to an approach which gives them a sense of being patronised, demeaned and disempowered, adds to their feelings of inferiority and reduces confidence in the caregiver. Nurses working with people who have long-term conditions will naturally experience a range of emotions when confronted with very real manifestations of human vulnerability. Distancing might provide short-term protection in shielding these emotions but accentuates the space between nurses and stigmatised people.

How prevalent are long-term conditions and disability?

The prevalence of long-term conditions and disability is difficult to establish. This is due in part to their inherent interactive, dynamic, multidimensional and subjective natures. Estimates in the UK are also not definitive, given differences in definitions, sampling and data capture. Although separate registers are maintained by local authorities and the Department of Health (DH) for those who are ‘sight impaired/partially sighted’ or ‘severely sight impaired/blind’ (see Ch. 13), there is no single register of disabled people and individuals do not have to be registered with local authorities to be defined as disabled or to receive services. In addition, sampling only private households excludes people living in communal establishments, a situation more likely for people severely impaired by long-term conditions. Not all disabled people claim benefits, so capturing data only from recipients of these also provides a limited picture.

The DDA 2005 changed the definition of disability so that people with cancer, multiple sclerosis and HIV are covered by its provision automatically from the point of diagnosis, as opposed to when their conditions affect them adversely day to day. Conditions otherwise covered can include cardiac disorders, hearing or sight impairments, significant mobility difficulty, mental health conditions and learning difficulties (Equality and Human Rights Commission 2007). Despite reference to impairment, this definition is, therefore, allied to the medical model. It is possible that individuals with the conditions named might not identify themselves as disabled and be missed from data collection.

Some indication of prevalence can be derived from studies accounting for variables including demography and morbidity but the complexity of this issue is mirrored in a review commissioned by the UK Department of Work and Pensions (DWP). This provides a flow chart for choosing the most appropriate estimate of disability according to purpose, via age grouping and definitions. The latter include health status, capacity for paid work, and coverage under the DDA or the WHO classification mentioned above (Bajekal et al 2004).

Consequences of changing morbidity and mortality

Improvements in public health have almost eradicated some infectious diseases, while others have been largely controlled by vaccination programmes. In addition, infectious diseases are generally amenable to treatment and therefore long-term rather than infectious disease remains the major cause of death and disability (Health Protection Agency [HPA] 2005). However, it must neither be assumed that infection has been eliminated from Western societies nor that long-term conditions cannot be infectious; AIDS is the result of infectious disease, yet to contract it means living with a long-term condition.

Continuing decline in mortality from infectious disease is reflected in an increased expectation of life for all age groups, a trend liable to continue. This has implications for the number of people experiencing long-term conditions and disabilities because the prevalence of these rises with advancing age. Confirmation of this can be found in data from sources such as the UK Census, General Household Survey (GHS) (latterly known as the General LiFestyle Survey or GLF) and Labour Force Survey, all of which use variants of the most widely used method of assessing activity limitation – the self-reported limiting long-term illness (LLTI) or disability question (ONS 2004, 2006). This generally involves asking respondents whether they have any long-standing illness, health problem or disability and whether this limits their activities in any way.

The national picture

In the 2001 Census, an LLTI or disability was reported by 10.86 million people, representing 18.47% of the UK population. Of these, 10.3 million lived in private households and the remainder in communal settings. Rates of LLTI or disability increased steadily with age, though gender differences were relatively small until the age of 60. Just over 10% of males and females aged between 35 and 39 years reported an LLTI, while in the 60–74 age group, 41% of males and 38% of females fell into this category. Rates among those aged over 90 were 69% and 78% respectively. Geographical comparison across the UK shows that England has the lowest rates, with Wales and Northern Ireland having the highest (www.statistics.gov.uk/census).

Census questions have not concerned types of long-term conditions and disabilities experienced or how these limit activities. Although the GHS samples only private households, it asks about the nature of health problems, coding replies according to the International Classification of Disease. Data from the 2002 survey show the prevalence of long-standing illness in children and adults to have risen from 21% to 35% between 1972 and 2002, while LLTIs have increased from 15% to 21% (www.statistics.gov.uk/ghs).

There is striking similarity between the proportions of men and women experiencing various long-standing conditions, with the following two exceptions among those aged 75 years and over. First, 27% of men stated they had a long-standing musculoskeletal disorder, compared with 42% of their female counterparts. This could be partly due to women’s longevity. Secondly, 11% of males identified themselves as suffering from respiratory disease, whereas only 7% of women characterised themselves in the same way. Differences in lifetime smoking behaviour are reflected here, although occupational factors could also be significant (Box 32.4).

The 2002–3 Family Resources Survey (www.statistics.gov.uk/surveys) asked respondents with LLTIs to identify their limitations or disability from eight categories offered. Mobility was most commonly named by over 60%, a similar percentage had difficulty with lifting, carrying or moving objects, and 25% experienced this with manual dexterity. Problems with memory, concentration and learning, continence and communication were less prevalent.

Features of living with long-term conditions

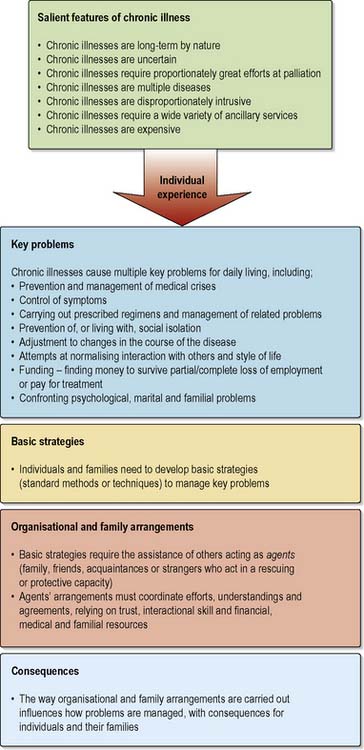

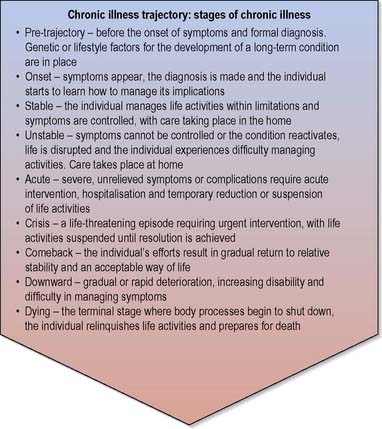

While prevalence data are helpful in predicting the demand for resources, they give no indication of the impact of long-term conditions on daily life. Overemphasis on diagnosis and disease conceals both the psychosocial problems shared by people living with them and the uniqueness of individual experience. It is only when aware of these that nurses can begin to appreciate the profound effect such conditions have on individuals, relatives/friends and health workers. In their seminal work, Strauss et al (1984) identified seven features of chronic illness and developed a framework to enable its impact to be understood more clearly and empathically (Figure 32.2). This was furthered in the subsequent development of a trajectory model which aimed to give insight into experience over the course of an illness over time (Corbin & Strauss 1991; Figure 32.3). These models are drawn on in the next section of this chapter.

Figure 32.2 Strauss et al’s (1984) features of chronic illness and framework for understanding individual experience.

Figure 32.3 Stages of chronic illness, as featured in the trajectory model. (After Corbin & Strauss 1991 and Ballard 2007.)

Endurance

The time span of acute illness contrasts markedly with that of long-term conditions. Once treatment is initiated, acute illness is generally resolved within a short period and life is resumed as before, whereas the duration of long-term conditions is indefinite. Their presentation is as varied as the conditions involved. For example, some might be evident at birth, while the onset of others results from injury or occurs over time. Regardless of this, individuals and their families are faced with adjusting life to accommodate the presence, unpredictable course and treatment of something which might be controlled but never cured. Building on Curtin & Lubkin’s (1998) metaphor, this can be likened to a stranger arriving at someone’s home unexpectedly and announcing that they are taking up permanent residence, regardless of whether there is a vacant spare room.

Although diagnostic labels often come as a relief because they explain symptoms and validate individuals’ feelings that ‘something isn’t right’ (Locker 2008), labelling also represents a defining moment in the trajectory from person to patient. For example, after being told he had Addison’s disease, one man told of a heightened sense that ‘things would never be the same again’, while a horse rider who sustained a spinal cord injury in a fall felt this when the trauma team started talking about her transfer to a spinal injuries unit.

Living with a long-term condition impinges on domestic, work-related and social activities. Experience leads individuals to develop a repertoire of strategies for managing their conditions around these. For instance, when attending events where food and drink are available, some people with diabetes mellitus are guided by their condition, rather than purely by desire. If they do not wish to bring this to wider attention, they might avoid alcoholic drinks on the pretext of wanting to ‘keep a clear head’. Conversely, others might learn to alter their insulin injections to allow for indulging in food and drink which they actually prefer. Creative non-adherence (Taylor 2008) to treatment or ‘intelligent cheating’ is common in long-term conditions. It can result in errors but careful adaptation actually reflects individuals’ assertion of control, successful renegotiation of life situations in their own context. Strategies used can require the ongoing assistance of relatives, friends, acquaintances or strangers who might function in various ways to assist in maintaining treatment programmes or protect the individual from harmful effects of the disorder. For example, someone with epilepsy might need help from workmates such that harmful objects are moved should an unexpected seizure occur.

The enduring nature of long-term conditions also results in repeated interaction between individuals and service providers, perhaps over a period of months or years. This leads to individuals becoming familiar with organisations and staff with whom they come into contact, having implications for the development of complex relationships between them. Familiarity helps staff in monitoring self-management and detecting subtle changes in health but can make maintaining social boundaries difficult. Frequent attendance with problems that are vague or irresolvable can also mark patients as unpopular. Individuals might be encouraged to relinquish control to health workers, though this stance is opposed in patient-focused rehabilitative care and by policies emphasising the importance of self-management in long-term conditions (Jester 2007). Depending on the dominant approach in a particular setting, either asserting oneself or passivity can be regarded as resistance to adopting the patient role and result in individuals acquiring a reputation for being ‘demanding’ or ‘difficult’.

Uncertainty

Adulthood is associated with the achievement of socially and culturally specified life goals such as leaving the parental home, beginning a career and finding a partner (Schaie & Willis 2001). The restriction, discomfort and possible dependence that accompany long-term conditions may force the individual to forgo these or adopt an alternative lifestyle. Biographical disruption (a term used to describe the way individuals with chronic illness are faced with losing life as lived previously, sense of self in relation to this and their vision of the future) leads to grieving for previously taken-for-granted opportunities and ambitions (Box 32.5).

Box 32.5 Reflection

Living with biographical disruption

Activity

Fear of dependence, which in itself causes uncertainty, is a fundamental human concern in cultures valuing self-reliance and physical and economic independence. Following diagnosis this problem is shared to an extent by health workers who must decide how much to share regarding the likely course of conditions and difficulties of treatment. Although it is seen as important to provide sufficient information to enable patients to exert maximum control over their situation, staff might question this in situations where only limited solutions can be offered. They might also withhold information to avoid destroying hope, for example when presenting the realistic survival gain of palliative chemotherapy (Audrey et al 2008).

The impact of fluctuation

Fluctuations in symptoms, and energy to manage them, make it impossible to forecast the occurrence of ‘good days’ and ‘bad days’ and this is compounded because a ‘good day’ can turn abruptly into a ‘bad day’ and vice versa. Uncertainty is also present because many long-term conditions are episodic, involving recurrent unpredictable exacerbations, followed by periods of remission or control. Since the onset and duration of exacerbations cannot be anticipated, individuals and their carers must be vigilant for them and ready to respond at any time. This means that individuals and their families can find it difficult to maintain continuity or plan their activities ahead and, as a result, cannot participate fully in community life. Friends might, for instance, eventually hesitate to extend invitations when people have repeatedly refused or withdrawn from events. Regret, resentment and social isolation can follow as activities are curtailed (Biordi & Nicolson 2009).

Fluctuation in long-term conditions also influences the way in which individuals perceive themselves and are perceived by others. Crucially, the invisibility of some conditions can cause others to question the reality of their experience and even doubt that it exists. For example, when people comment ‘but you look so good for someone who has MS…if they can’t see it, there really isn’t anything wrong with me’ (National Multiple Sclerosis Society 2007), the subtext is ‘You can’t be sick, you’re just faking it’ (Anon 2007). This means that the consequences of living with a long-term condition are disregarded. Individuals are believed to be directly affected only when it becomes noticeable, so variation in ability, during a particular day or period of exacerbation, is misunderstood. Nurses lacking knowledge of long-term conditions can be quick to make judgements as to why people could perform activities yesterday but not today or cannot be certain of their capability for tomorrow. This can have harmful consequences. For instance, staff caused an immobile man with Parkinson’s disease considerable distress when they implied he was lazy because they had seen him walking previously. He was actually unable to move due to the unpredictable ‘on-off effect’ associated with his response to long-term medication.

Beneficial effects of uncertainty

Paradoxically, uncertainty in long-term conditions can be perceived positively as an opportunity to reappraise life’s possibilities (Bailey et al 2007). Whether of sudden life-changing onset or signalling that changes will occur, diagnosis can prompt individuals to reflect on the way life had been lived and to search for new meaning in exploring events, reprioritising and seeking new challenges. As one person explained: ‘If anyone asks, I tell them I wouldn’t do away with having had my stroke now. Yes, I’d do away with its problems but I’ve learned who my real friends are, that I don’t want to spend all my waking hours in the office and discovered I can do things I’d never thought of as “me” before too – like disability sport and joining a service users’ group’. Uncertainty can also motivate concordance with treatment, since this provides a tool for maintaining some stability.

Palliative emphasis

Individuals have considerable personal resources and many use these to try to resolve problems before seeking official help or as an adjunct to it, particularly if these agencies cannot provide palliation or the side-effects of treatment are intolerable. Complementary therapies are used commonly by people who feel that orthodox medicine has nothing further to offer but, in long-term conditions, this also represents assumption of control where it otherwise seems to have been lost. Furthermore, in contrast with conventional care, there is a possibility of accessing person-centred treatments which are inherently pleasurable, providing individuals with the potential for taking responsibility for their well-being in its wider sense and developing skills to manage a range of stressors (Cartwright & Torr 2005). This is important because stress both results from the experience of living with long-term conditions and exacerbates symptoms, being associated with relapse. Mental distress can also lead to the development of anxiety-related and depressive disorders. Stress management is aided by therapies that pay explicit attention to the mind–body relationship, and approaches that mobilise individuals’ inner resources, such as mindfulness-based interventions (Kabat-Zinn 2001), are also practised alongside conventional treatment. Management strategies can also be learned through experience and membership of self-help groups.

The UK Government’s Expert Patients Programme (EPP) initiative is integral to policies aimed to modernise the NHS. It stems from recognition that traditional cure-oriented services have not dealt comprehensively with problems faced by people with long-term conditions and that partnership enhances self-efficacy (DH 2001a). Consistent with this, EPPs are led by lay people rather than health care professionals. Depending on local health service targets, they can be organised along generic lines or for condition-specific groups, although the latter limits participation and marginalises people with other diagnoses. EPPs aim to increase people’s confidence, resourcefulness and control, thereby improving quality of life and reducing service use. Underlying principles are reflected in service development and governance, for example the English National Service Framework (NSF) for long-term (neurological) conditions (DH 2005) and other disorder-specific strategies. Examples of such frameworks for diabetes may be found across the UK (DH 2001b, Scottish Executive 2002, Clinical Resource Efficiency Team [CREST] 2003, Welsh Assembly Government 2003).

Co-morbidity

The systematic and degenerative effects of many long-term conditions mean that the failure of one organ or system leads eventually to the involvement of others. For example, the complications associated with diabetes mellitus include vascular damage, which might result in renal and visual impairment, and an increased risk of myocardial infarction. Impaired circulation to the lower limbs also predisposes to the development of gangrene, the onset of which is, in turn, influenced by degeneration of the nervous system and greater susceptibility to infection (Crumbie 2002a). Amputation of an affected limb leads to further alteration of physical, psychological and social functioning. Clearly, the effects of long-term conditions are compounded by the consequences of treatment used. Efforts to adjust to reduced activity are also complicated by multiplication of symptoms and resulting impairment. For example, chronic pain both inhibits movement and correlates with atrophy in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, which impairs decision making.

Health care professionals can be perceived as being incapable of resolving certain issues or, in the case of problems arising from treatment, as actually responsible for them. This has obvious implications for the quality of nurse–patient relationships, which to be genuinely therapeutic must be characterised by mutual trust and cooperation (Box 32.6).

Box 32.6 Reflection

Different approaches to managing a long-term condition

Activities

Reflecting on L’s circumstances:

Intrusiveness

A significant aspect of living with long-term conditions is the ‘daily grind’ of monitoring and managing their features (Locker 2008). Such work is unrewarding, unrelenting and inescapable. As someone with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) explained: ‘For one wonderful moment when you wake up you forget. But there it is. Again. Any novelty around pills and things has gone and there’s no time off’. Becoming accustomed to this is challenging because it involves a fundamental shift from the former self and life towards recognition and acceptance of a ‘new normal’ (Fennell 2003).

Loss, grief and adaptation

Grief experienced in long-term conditions resembles that in bereavement. It can be associated with loss of a body part, image, function, social status or role and can occur suddenly when a long-term condition is acquired or over time as it progresses. People can also experience loss of identity because it reflects their previous, non-impaired self and they feel they have become less of a person than they were. Awareness of models of grief or response towards threat to self-integrity (e.g. Kubler-Ross 1969 and Morse 1997 respectively) guides nurses in supporting individuals to work towards adaptation to unwanted change. However, care must be taken not to apply these prescriptively because personal reactions differ. Falvo (2008) identifies a general path beginning with shock, numbness and disbelief, when the diagnosis or the severity of the condition is denied. This is followed by acknowledgement of the situation’s reality, when grief intensifies. Continued exposure to the loss can lead individuals to adjust and come to emotional acceptance but this is not guaranteed. The process is painful, unpredictable and fluctuates in their struggle to manage the powerful reactions created, as shown in Rushby-Smith’s (2008, p. 210) thoughts on life after spinal cord injury. ‘For most of the day I’m in pain. I get frustrated that I can’t reach things, climb things, negotiate stairs, step over things, bounce my daughter on my knee […] At the end of every day I am filled with a mixture of rage and utter debilitating terror, as I struggle to accept that this is me this is happening to, and that I will never get back my life as I knew it.’

For some, grief remains unresolved and can be more disabling than the condition itself. Here, it is essential for nurses to recognise the meaning of what has been lost and understand that addressing this is key to renewing self-identity (Telford et al 2006). Again, this means considering bio-psychosocial issues beyond diagnostic labels and accounting for other health problems present. For example, following traumatic injury, a researcher adjusted to physical impairment with relative ease but had difficulty in accepting the continuing impact of a stress-related anxiety disorder. He felt profoundly diminished by the realisation that his hard-worked-for career would not progress as planned, having to regard as a real achievement the completion of workplace activities he previously undertook without thinking and depending on his partner for reminders about household tasks. This was compounded by a nurse saying he was fortunate: ‘but my ability to rely on my mental sharpness and function under pressure is important – it’s who I am. I just can’t get past that. I feel like a champion runner who battles daily to stumble round the block and is expected to be grateful for it’.

In acute illness it is feasible and acceptable to gain temporary exemption from normal social obligations; however, this is not always possible for people with long-term conditions. Parson’s (1951) conceptualisation of the sick role makes sense of illness as a social state, but its applicability is questionable in this context, since it implies a duty to recover. The sick role does, however, grant medically mediated access to services and explains why the concordance of people with long-term illness with treatment is expected in the same way as those who are acutely ill (Field & Kelly 2007).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree