Acute severe breathlessness 11

Sudden cardiac death 39

Infective endocarditis 49

Drugs in the management of acute heart disease 51

Introduction

In many cases, however, the diagnosis will not be clear-cut. This is particularly true in the elderly, in whom the presentation of acute cardiac problems ranges from sudden confusion to abdominal pain and vomiting. Often, the clinical picture may overlap with non-cardiac conditions. The classic situation is difficulty in differentiating cardiac and respiratory breathlessness in patients with the common combination of COPD and ischaemic heart disease. Other examples include abdominal symptoms in congestive cardiac failure, and cachexia with weight loss in advanced decompensated valvular heart disease.

All these patients will be admitted to the Acute Medical Unit, where the expectation is that they will be assessed, diagnosed and appropriately treated with the minimum of delay. The patients, particularly those who are older than 75 years, frequently have several medical conditions and when admitted are receiving complex treatment regimens. It is often the case that cardiac problems complicate other diseases that themselves were the reason for admission: the patient with anaemia from GI blood loss who develops angina after admission is a typical example.

The task for the nurse is to perform an accurate assessment that takes into account both cardiac and non-cardiac aspects of the patient’s medical history. The patient’s problems must be prioritised: for example, increasing angina will take priority over a recent change in bowel habit, and attacks of nocturnal breathlessness will be more urgent to address than newly diagnosed but stable Type II (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes.

The management of heart disease must be based on an understanding of the underlying conditions, particularly ischaemic heart disease (coronary artery disease), cardiac failure and atrial fibrillation. There have been important advances in the diagnosis and management of these conditions that have altered our approach to patients:

• Active management of myocardial infarction

— the use of troponin-T and other markers for risk stratification

— urgent re-perfusion by medical intervention and/or balloon angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction

— aspirin prophylaxis

— referral of unstable patients for CABG or angioplasty

• New approaches to cardiac failure

— the use of ACE inhibitors (e.g. enalapril)

— the use of low-dose beta-blockers

— new pacing and electrophysiological techniques

— effective antiarrhythmic drugs: amiodarone and flecainide

• Recognition of the frequency and significance of atrial fibrillation

— increased use of anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation

This chapter aims to provide the basis for this understanding by looking at disease mechanisms and by providing a logical approach to the patient with possible heart disease.

Common Clinical Problems

Acute severe breathlessness

Acute severe breathlessness is a common problem on the Acute Medical Unit, but there is often a diagnostic dilemma in deciding between pulmonary oedema and asthma or COPD (→Chapter 3; The breathless patient: the general approach). This chapter looks at the mechanisms and causes of cardiac failure, which will put into context both the clinical features and the management strategy of the patient with pulmonary oedema or congestive failure.

Chest pain and atypical myocardial infarction

The various clinical problems associated with ischaemic heart disease – infarction, angina and silent myocardial ischaemia – will be described. The chapter aims to clarify the management of chest pain, in particular how to assess the urgency of the situation in a new patient.

Atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia encountered on the emergency ward. It causes cardiac failure, syncope and unexplained dizziness, and can complicate any severe febrile illness such as pneumonia or exacerbations of COPD. Atrial fibrillation is a common cause of stroke and is one of the major indications for anticoagulant therapy. The management of atrial fibrillation encompasses the use of a good assessment technique, a working knowledge of modern cardiac drugs, and the ability to recognise and deal with complications such as cardiac failure and angina in an acutely distressed and anxious patient.

Immediate relevance of heart disease to other acute medical conditions

When assessing an unstable patient with any acute medical condition, it is important to consider the risk posed by any coexisting cardiac problem to the safety of the patient:

• Medium risk

— stable angina

— previous myocardial infarction

— previous cardiac failure

• Low risk

— poorly controlled hypertension

— previous CABG, but now asymptomatic

— angina, but comfortable at a normal walking speed

Any patient within the first category needs to be assessed immediately and with particular care, and there should be no hesitation in involving medical staff if problems arise. In contrast, the cardiac conditions in patients in the medium- and low-risk categories are less likely to be immediately relevant to an acute admission, particularly during the first 24h of their admission. Box 2.1 lists some key questions that arise in the treatment of cardiac patients.

Box 2.1

• Is this chest pain cardiac in origin?

• What is the difference between cor pulmonale and congestive cardiac failure?

• How do I approach acute dyspnoea in an asthmatic with known heart disease?

• The pulse is 135 beats/min: what is the next step?

• Why is this patient cold, clammy and shut down?

• Why are nitrates used to treat angina as well as pulmonary oedema?

• Why can morphine be used for acute LVF but not for treating asthma?

• Does this patient need urgent medical attention?

• How can I make sense of this patient’s drug regimen?

• What can I say to the relatives of this patient with acute pulmonary oedema?

Core Nursing Skills

Application of triage using ABCDE (→p. 2; primary assessment)

The essential skill of cardiac nursing is to establish the safety of the patient. As with any acute illness, this is based on basic observations of the vital signs. The immediate priority is to establish adequate oxygenation and an effective circulation. In pulmonary oedema, for example, the patient can be so ill that other nursing considerations are overshadowed by the need to administer opiates, oxygen and intravenous (i.v.) frusemide to save the patient’s life.

Reassurance of acutely distressed and anxious patients

The patient will be acutely unwell, with a combination of unpleasant and frightening symptoms: severe breathlessness, chest pain, rapid irregular palpitations and overwhelming fatigue. Not surprisingly, cardiac patients are among the most frightened and anxious, and this will not be helped by hearing staff talk of heart ‘failure’ and ‘unstable’ angina. Anxiety worsens breathlessness, can exacerbate angina and will put an extra load on the heart. Reassurance is vital and this is best provided by nurses who understand exactly what is wrong and why and who can explain the details of their management. It is easy to forget, for example, that patients who are having intensive nursing observations and complex tests carried out may feel very anxious that they are not being told what all this information means and whether they are in fact going to recover.

Resuscitation skills

Acute cardiac illness is characterised by rapid changes in the patient’s condition. The most difficult problems encountered on the Acute Medical Unit are fulminating pulmonary oedema with hypoxia and hypotension and the unexpected cardiac arrest. It is therefore important that all the staff are fully trained in CPR and are familiar with the resuscitation equipment.

Coordinated care with the medical staff

There is considerable overlap between nursing and medical responsibilities in the care of patients with acute heart disease. The initial nursing assessment will include important diagnostic information: the nature of the predominant symptoms and the identification of ischaemic chest pain are two obvious examples.

Subsequently, documentation of the trends in the vital signs, urine output and symptomatic improvement is the main way that the patient’s response to treatment is evaluated. It is important that all this information is shared constructively with the medical staff and that the duplication of tasks such as history taking and observations is kept to the absolute minimum, both to save time and to reduce the burden to the patient.

Anticipating problems

With experience backed by a good understanding of the underlying disease mechanisms, some problems can be anticipated and often forestalled.

Obvious examples include the hypotension that can complicate the use of several cardiac drugs and the development of ischaemic chest pain in a patient who develops rapid atrial fibrillation. It can be extremely helpful to assess the way in which the patient has responded to similar situations in the past by examining the hospital records and noting what the patient and their relatives have to say about it.

Cardiac Failure

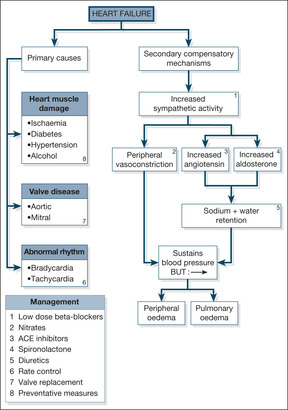

There are two components to heart failure: the primary problem, which damages the function of the heart, and the secondary mechanisms, which are activated to try and compensate for the impaired cardiac function. These are summarised in Fig. 2.1.

Primary Problems in the Heart

Heart muscle damage

The most common cause of chronic heart failure is heart muscle damage from myocardial ischaemia due to coronary artery disease. Most patients give a history of long-standing angina and recurrent myocardial infarctions, but a significant proportion of cases, particularly patients with diabetes, have unrecognised silent ischaemia that presents for the first time as cardiac failure. Hypertension is also an important cause of cardiac failure. The response to long-standing, uncontrolled hypertension is an increase in the bulk and strength of the heart muscle in order to drive blood out of the heart against the increased pressure. In time, however, the muscle fatigues and weakens, leading to reduced cardiac reserve and eventual failure.

Other causes of heart muscle disease are listed in Fig. 2.1. Of these, alcoholic cardiomyopathy is probably the most important, as it is common and will respond to the combination of alcohol withdrawal and thiamine (vitamin B) replacement.

Valvular disease

Although not as common as heart muscle damage, valvular disease can lead to chronic cardiac failure that, with correct management, can be alleviated or controlled. Heart valves normally act as one-way doors which ensure that, when the heart contracts, blood can pass in only one direction. To continue the analogy with a door – as a result of damage (e.g. past rheumatic fever or a congenital fault in the valve’s structure) the valve can become permanently stuck half-open (stenosis), in which case the heart has difficulty expelling blood through it. This has two important consequences: the heart may become overworked, and blood may dam up behind the stenosed valve.

Alternatively, a valve can lose its one-way facility so that, instead of its being normally closed in either systole or diastole (depending on which valve is being considered), blood can pass through it throughout the cardiac cycle: this is known as valve incompetence or valve regurgitation. In valve incompetence/regurgitation, the affected chamber not only has its normal quota of blood to expel each beat, but it also has the added amount that comes back to it as a result of the leaking valve. Thus, in mitral incompetence, during left ventricular contraction blood leaves by the usual route into the aorta, but some blood is also forced back into the left atrium through the incompetent mitral valve. This blood then returns, along with the normal quota of blood, during the subsequent diastole. In aortic incompetence, blood leaks back into the left ventricle during diastole, when the aortic valve should normally be closed. The left ventricle has to deal with this back-flow in addition to the normal amount coming to it from the left atrium. In time the heart muscle fatigues, either because of the extra pressure it has to generate (in, for example, aortic valve stenosis) or because of the extra volume of blood it has to cope with (in, for example, mitral valve incompetence). This fatigue, in turn, in time leads to clinical cardiac failure.

Rhythm disturbance

Abnormally slow (bradyarrhythmias) or, more commonly, abnormally fast (tachyarrhythmias) cardiac rhythms can result in heart failure. A slow pulse leads to a fall-off in the cardiac output, simply because the heart beats less often per minute. A healthy heart compensates for a slow pulse by having more time to fill before each contraction; the heart chamber responds to such stretching by producing a more forceful contraction, expelling an increased amount of blood. A diseased heart is unable to respond in this way, so that a reduced heart rate causes a reduced cardiac output. Fast rhythms disrupt the events that occur during diastole – filling of the heart chambers and blood flow down the coronary arteries. Once again, a healthy heart can cope with a rapid rate, but a diseased heart can soon be compromised, particularly if the coronary arteries are narrowed. The most common rhythm disturbance to cause or contribute to cardiac failure is uncontrolled atrial fibrillation, in which the rate is both rapid and irregular. The onset of rapid atrial fibrillation can often trigger acute heart failure.

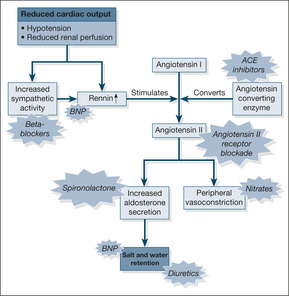

Secondary Compensatory Mechanisms in Cardiac Failure

In response to the basic problem of reduced cardiac output, two compensatory mechanisms are activated to try and maintain a normal blood pressure:

1. increased sympathetic nervous system activity (exaggerated stress reaction)

2. activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone hormone system (salt and water retention)

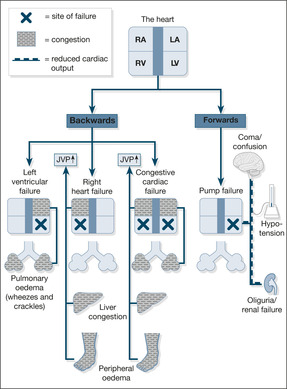

These two mechanisms respectively increase the narrowing of the peripheral arterioles and increase the circulating blood volume – a strategy designed to keep the blood pressure up and maintain a good blood supply to the kidneys. Although this may work for a while, ultimately it leads to an increased load against which the heart must pump (in the case of the narrowed arterioles) and pulmonary congestion and ankle oedema (in the case of the increased circulating blood volume). Pumping against an abnormally high load eventually leads to heart muscle fatigue, so-called pump failure or ‘forward’ heart failure (low blood pressure and poor organ perfusion). Conversely, the congestive component is known as ‘backward’ failure (pulmonary and peripheral oedema). These two components of cardiac failure are summarised in Fig. 2.2.

Modern management of cardiac failure aims to reverse these mechanisms by decreasing the resistance against which the heart must pump and unloading the congestion behind the failing heart. As shown in Fig. 2.3, this is achieved by:

• dilating the arterioles (e.g. GTN, isosorbide mononitrate, hydralazine)

• reducing the salt and water retention (e.g. frusemide and bumetanide)

• inhibiting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, aldosterone antagonists)

• reducing sympathetic activity – the cautious use of sympathetic blockade (beta-blockers) e.g. carvedilol

An important new biomarker of cardiac failure: B-natriuretic peptide

There are two important clinical implications. First, the blood test can help diagnose cardiac failure and will become particularly helpful in patients in whom the underlying cause of their acute breathlessness is unclear. Normal BNP levels in a patient with acute severe breathlessness rules out cardiac failure as the underlying cause. Secondly, drugs with the same chemical properties as BNP are being developed to exploit its effects on reversing the underlying mechanisms in cardiac failure.

Types of Heart Failure

Left heart failure

In left heart failure, the clinical problem is dominated by the build-up of fluid in the lungs, because the failing left ventricle cannot cope with the increased circulating blood volume – blood dams up behind the left side of the heart, producing pulmonary congestion and pulmonary oedema. The symptoms of left heart failure are:

• breathlessness on lying flat (orthopnoea)

• PND

• coughing frothy pink sputum (alveolar oedema)

Right heart failure

In right heart failure, the right ventricle cannot cope with the increased circulating blood volume and blood dams up in the veins, leading to congestion of the liver, ankle oedema and oedema over the sacrum. The symptoms of right heart failure are:

• swollen ankles

• liver discomfort

• abdominal swelling (ascites)

Congestive cardiac failure

In congestive cardiac failure, there is a combination of left- and right-sided failure, giving a constellation of symptoms that include:

• breathlessness

• fatigue

• pulmonary and ankle oedema

Diastolic heart failure

Diastolic heart failure is a newly recognised condition which may account for a fifth or more cases of cardiac failure. Typically seen in elderly, obese, hypertensive and diabetic women, diastolic failure results from an abnormally hypertrophied and stiffened ventricle, which contracts well enough but in diastole cannot relax sufficiently to accommodate returning blood. The symptoms – pulmonary and peripheral oedema – are the same as in other forms of failure; the diagnosis relies on the characteristic changes on an echocardiogram.

Clinical Features and Management of Cardiac Failure

Characteristics of patients admitted acutely with cardiac failure

In general, patients with heart failure comprise an elderly group of patients, average age around 75 years, with a strong preponderance of ischaemic heart disease – half will have had a previous infarct. At least half of all these patients will be in atrial fibrillation, and for about a tenth the heart failure will have been triggered by their first attack of atrial fibrillation. One-third will also have COPD and a fifth will be diabetic. In the majority, around 80%, the cause of the failure will be associated with poor heart muscle function; valve problems will only be seen in about 10% of the patients.

It can be helpful to characterise the patient’s pre-existing level of disability. The NYHA classification is the one most commonly used:

• Class I – no limitations (no fatigue, breathlessness or palpitations)

• Class II – slight limitations, fine at rest, but ordinary exertion leads to symptoms

• Class III – marked limitations, fine at rest, but symptoms on less than ordinary exertion

• Class IV – symptoms at rest

Patients in NYHA Classes III and IV have a poor outlook, with 5-year mortality rates approaching 50%.

Principles of managing cardiac failure

2. In addition, or as an alternative, the compensatory mechanisms that are responsible for the clinical picture of chronic cardiac failure are addressed:

— reducing fluid retention (diuretics)

— reducing the load on the heart (vasodilators)

— counteracting excessive sodium retention (ACE inhibitors such as enalapril, angiotensin receptor blockers such as losartan)

— counteracting increased sympathetic activity (low dose beta-blockers).

There is an obvious risk in correcting what are supposed to be compensatory mechanisms – in particular, over-diuresis and excessive use of vasodilators can produce hypotension, with a worsening of tissue perfusion.

3. Cardiac resynchronisation therapy

In some patients with cardiac failure, delayed electrical activation of the left ventricle (recognised on an ECG by the pattern of left bundle branch block) produces a disjointed and inefficient cardiac contraction. If severely impaired, the contractile state can be resynchronised and improved using a novel permanent pacemaker which, unlike conventional pacemakers, paces the left as well as the right ventricle. This technique, termed dual-chamber pacing, will have an increasing role in selected cases of cardiac failure, although the effects on quality of life surpass those on actual survival.

Patients with heart failure are at least six times more likely to die suddenly than the general population. In carefully selected patients, ICDs can be fitted to reduce mortality by treating any lethal ventricular arrhythmia.

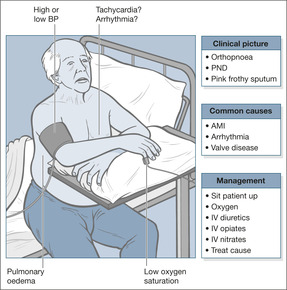

Acute left ventricular failure

Acute LVF (→Fig. 2.4) is a common cause for acute life-threatening breathlessness (the others being acute asthma, tension pneumothorax and pulmonary embolism). Case Study 2.1 illustrates the typical picture in heart failure due to ischaemic heart disease. Interestingly, the patient did not receive an ACE inhibitor after his infarct; these are now given routinely as post-infarct prophylaxis to lessen the risk of developing heart failure.

Case Study 2.1

A 62-year-old man with a previous myocardial infarct was admitted with a 3-week history of increasing breathlessness. He had no other illnesses and was only taking low-dose aspirin. His blood pressure on admission was 180/120 mmHg, the ECG showed heart strain and the chest film showed LVF. Urine testing showed proteinuria. His kidney function was normal.

Initial assessment was of a distressed and overweight man with a resting pulse of 120 beats/min which felt regular, a respiratory rate of 35 breaths/min with an audible wheeze, oxygen saturation on air of 85% and a blood pressure of 180/120 mmHg. His peripheries were cold and clammy and capillary refill time was prolonged. He complained of breathlessness but no chest pain.

The patient was propped upright and given high-flow oxygen; an intravenous cannula was inserted and blood was taken, primarily to check the kidney function, cardiac enzymes, sugar and full blood count.Arterial blood gases were checked.An ECG monitor to identify arrhythmias and an oximeter to confirm adequate oxygenation (saturations more than 94%) were attached to the patient. He was given:

• i.v. frusemide 80mg

• i.v. diamorphine 2.5mg

• cyclizine as an antiemetic

Oxygen saturation increased to 94% and the respiratory rate decreased to 25 breaths/min; his pulse remained high at 120 beats/min.The patient passed 1L of urine in the first 1h of admission, but remained breathless.

An infusion of GTN was started and plans were made for a trial of an ACE inhibitor.

Critical nursing tasks in acute LVF

Ensure the patient is adequately oxygenated

Patients in acute LVF die of hypoxia due to pulmonary oedema. Therefore the safest practice is to start with high-flow oxygen or a non-rebreathing mask, aiming to give the patient at least 60% oxygen. This can be modified in the light of the oxygen saturations or blood gas measurements. The target oxygen saturation is between 94 and 98%. Patients must be propped upright – even if they are hypotensive. Their symptoms will improve because pulmonary oedema lessens in the sitting position.

The Boussignac CPAP mask in acute left ventricular failure

Acute pulmonary oedema with resistant hypoxia which is unresponsive to high-flow oxygen and diuretics may respond to short term (two hours) treatment with CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure). The Boussignac CPAP system uses a small lightweight plastic cylinder that is directly connected to a tight fitting face mask. It requires a standard oxygen supply to administer CPAP pressures up to 10 cm of water and inspired oxygen levels approaching 100%. It is suitable for use on acute medical wards providing there are adequate numbers of appropriately trained staff.

Measure the patient’s blood pressure

Hypertension. Many patients with LVF become acutely hypertensive as a stress response; the blood pressure settles as their condition improves. Less commonly, hypertension is believed to be the cause, rather than the effect, of a patient’s LVF. In such cases it is usually severe (e.g. 210/140 mmHg) and persistent, and has to be lowered as part of the patient’s immediate management. Fortunately some of the drugs used to treat LVF, such as nitrates and diuretics, have a dual effect: they both eliminate pulmonary oedema and reduce the blood pressure.

Hypotension. Hypotension in the setting of LVF is an unfavourable sign, particularly if blood pressure remains low after any abnormal cardiac rhythm has been corrected. It can indicate heart muscle damage, it limits the type and quantity of drugs that can be used – because several cause hypotension themselves – and it can put kidney function at risk. Persistent hypotension is an indication for inotropic support (drugs such as dopamine, which improve cardiac performance), particularly if the urine output is inadequate.

Evaluate the patient’s pulse rate. The analysis of the patient’s pulse rate is not easy from bedside observation, particularly if the patient is acutely ill, and a monitor and 12-lead ECG will be required. Nonetheless, atrial fibrillation (or its close relation, atrial flutter) is likely to be the cause of any rapid pulse of greater than 130 beats/min.

Occasionally, LVF can be accompanied by, and even caused by, an abnormally slow pulse. Drug treatment, in particular with beta-blockers, can be an important cause of this. The bradycardia resolves once the drug is withdrawn.

Important nursing tasks in acute LVF

Does the patient understand and comply with the oxygen therapy?

Ensure that the patient understands the need for continuous (as opposed to symptomatic) administration of oxygen. Is this reflected by appropriate improvements in the oxygen saturation?

Has the patient responded to the diuretic?

An immediate diuresis is a good prognostic sign, whereas failure to establish a diuresis, especially if it is accompanied by hypotension, suggests a problem with maintaining blood flow through the kidneys. It is important to exclude retention as a cause for a low output, particularly in older male patients. It is common practice to obtain an exact assessment of the urine output in critically ill patients by using a urethral catheter.

Is the patient less breathless and in a better clinical condition?

As the treatment takes effect, the patient should become less breathless; he will be less distressed and his respiratory rate will decrease.

As the heart picks up the peripheral circulation will also improve: extremities will be less clammy and the feet and hands will warm up – capillary filling should also improve.

Acute myocardial infarction can present as acute LVF and the chest pain may be ignored in the presence of severe breathlessness. It is therefore important to enquire specifically about pain and ensure that appropriate analgesia – morphine or diamorphine – is prescribed.

Have the blood pressure and pulse returned towards normal?

Acute on chronic congestive cardiac failure

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access