Nausea and vomiting Underlying mechanisms 158

Nausea and vomiting in acute medical conditions 160

Acute abdominal pain 188

Medical conditions presenting with gastrointestinal symptoms 199

Introduction

Other medical conditions also present with gastrointestinal symptoms: on our unit, we have recently seen two young patients presenting with acute abdominal pain, one with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and the other with meningococcal meningitis. Acute myocardial infarction, basal pneumonia and pulmonary embolus are all known to masquerade as an acute abdomen from time to time. More commonplace is the problem of nausea and vomiting – common diagnostic dilemmas in themselves, but also occurring as accompanying symptoms in diseases as diverse as cerebral haemorrhage and septicaemia.

The Acute Medical Unit nurse must be familiar with the causes and clinical course of the common acute gastrointestinal emergencies, in particular with the complications that can occur in the first 24h and which often determine whether the patient will recover. Nurses must also have a working knowledge of the common gastrointestinal symptoms that they will encounter – what will be the likely cause and what will be the best form of management.

Nausea and Vomiting Underlying Mechanisms

Nausea is one of the most distressing acute symptoms, but it is easy to relieve, provided that:

• the underlying mechanism is understood

• the cause is identified and corrected

• the appropriate drugs are used

Vomiting is a common but potentially serious problem:

• it can occur in response to a minor illness, but it can indicate serious disease

• it can itself lead to metabolic problems

The Patient Who is Vomiting: The General Approach

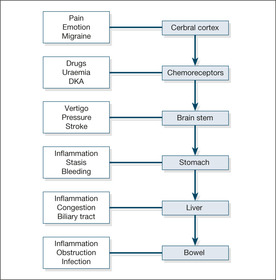

Consider the underlying mechanisms and potential causes (→Fig. 5.1)

Local gastrointestinal causes include acute gastritis and gastroenteritis (especially staphylococcal food poisoning), liver inflammation and cholecystitis.

Establish the history

• Did it occur in the setting of another illness?

• Is there pain anywhere?

• What other symptoms are present (e.g. headache, giddiness, abdominal pain)?

• Has it happened before?

• Has anyone else got the same symptoms?

Is this gastrointestinal disease?

• Is there any diarrhoea?

• Is there or has there been any abdominal pain? (Try to identify abdominal pain other than that due to the mechanical effects of retching.) Vomiting is a common feature of cholecystitis and pancreatitis

• Are there any features of obstruction (absolute constipation, cramps, abdominal distension, a tender lump in the groin may be a strangulated hernia)?

• Is the cause acute liver damage (hepatitis or paracetamol overdose)?

• Is there alcohol abuse?

Is this drug-related?

• What drugs have been started or increased in recent days?

• Is this digoxin toxicity/opiate side-effect?

Could this be raised intracranial pressure?

• What is the accompanying clinical setting?

— headache (meningitis/subarachnoid haemorrhage)?

— malignant disease (cerebral secondaries)?

— altered consciousness level (cerebral mass/encephalitis, etc.)?

Could this be metabolic?

• Is there renal failure?

• Are the sodium and calcium levels normal?

• Could this be ketoacidosis (the patient may be diabetic)?

Nausea and Vomiting in Acute Medical Conditions

Migraine

Migraine is commonly accompanied by vomiting. Other more worrying causes of headache – meningitis, increased intracranial pressure and subarachnoid haemorrhage – are also associated with vomiting, so the symptom itself is of little diagnostic help in this setting. In these situations, other features such as a skin rash or stroke-like symptoms help to clarify the underlying diagnosis.

Myocardial infarction

Vomiting is an important feature that distinguishes the pain of a myocardial infarction from that of angina and is often accompanied by nausea and sweating. In the elderly patient, vomiting may be the only symptom of a myocardial infarction.

Sepsis

Vomiting can be the only symptom of hidden infection, even of frank septicaemia, particularly in the elderly or immunocompromised patient. This is particularly the case in infections in the kidneys and lower urinary tract.

Acute gastric dilatation

Acute gastric dilatation is important because it is an easily preventable cause of sudden death. In this condition, gross gastric distension leads to upper abdominal swelling associated with nausea, often accompanied by hiccups and belching. These patients are often already unwell and a common outcome is sudden vomiting, aspiration and cardiorespiratory arrest. Factors that can trigger acute gastric dilatation include electrolyte disturbance, bacterial toxins and, most commonly, DKA. Treatment is simple – anticipate the possibility (in DKA, in severe infection and in any critically ill patient), recognise the condition, and prevent aspiration by decompressing the stomach with a nasogastric tube.

Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding is a common cause for acute admission. In a catchment population of 200 000, around 300 acute gastrointestinal bleeds will be admitted per year. Some will be trivial (a young man who has light blood streaking after repeated vomiting the ‘morning after’) and can be discharged home very quickly. The majority will be of moderate severity, can undergo endoscopy on the next available list and will stop bleeding of their own accord. A minority, however, will be lifethreatening and complex: a truly multidisciplinary approach will be needed, involving gastroenterologists, radiologists, surgeons and several junior doctors.

At the centre, in the severe cases, is the nurse. It is the nurse who will be the first to assess the initial blood loss, who will personally witness any rebleeding and who will be on the ward at critical times – when the patient returns from endoscopy, when the consultant surgeon arrives seeking an urgent update and in the early hours when the observations deteriorate. Also caught up in the frenetic activity will be a critically ill patient who, possibly in a confused and agitated state, may be frightened and uncertain about what is going on. The nurse’s role is:

• to ensure the immediate safety of the patient

• to assess the degree of initial blood loss

• to collect information for assessing the risk to the patient of the bleed

• to identify the earliest signs of re-bleeding

• to coordinate the management of fluid replacement, transfusions and fluid balance

• to reassure the patient and ensure that there is appropriate symptomatic relief

The are some critical issues in the presentation and management of gastrointestinal bleeding on the Acute Medical Unit:

• early diagnosis and adequate resuscitation are the keys to successful management

• patients with significant haemodynamic disturbance or who need transfusion will need urgent endoscopy

• patients who do badly are older, lose a larger quantity of blood and either continue to bleed or stop and then bleed again

• there is an overall mortality rate of 8–10%, which has not improved in recent years

• the mortality risk is almost entirely confined to patients over 60 years and with significant co-morbidity

Causes of Acute Bleeding

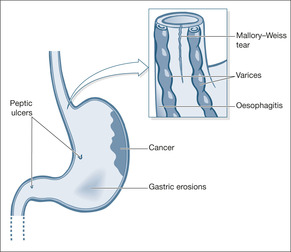

The success of the management of acute gastrointestinal bleeding lies in making an early diagnosis of its likely source. Unfortunately, there are several potential bleeding sites: from the oesophagus to the duodenum in patients with haematemesis and from the oesophagus to the beginning of the colon in patients with melaena. The cause of the bleeding determines the outlook: some types (e.g. gastric erosions) will always stop bleeding on their own; some will often need intervention (e.g. varices) (→Fig. 5.2). Once the initial bleed has settled, some lesions will have resolved completely (e.g. Mallory-Weiss tears), whereas others have a high risk of re-bleeding (e.g. arterial bleeds from a peptic ulcer). Diagnosis rests on knowing the likely source, bearing in mind the patient’s age (→Box 5.1) and history and, most importantly, the findings at early endoscopy – which ideally means within the first 24h of admission.

Box 5.1

| Young | Old |

|---|---|

| Mallory-Weiss tears– – – – – – Varices – – – – – – | Gastric/oesophageal cancer |

| Duodenal ulcer | Gastric ulcer |

| Acute gastritis | Oesophageal ulcer |

| Acute duodenitis | Oesophagitis |

Peptic ulcer disease

Duodenal and gastric ulcers are the causes in half of all cases of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Most ulcers (eight out of ten) stop bleeding of their own accord; the remainder need intervention at endoscopy (injection of the ulcer base with adrenaline (epinephrine)/coagulation with a heat probe or laser/clipping), in the radiology department (embolisation), or possibly by surgery. After a bleed patients require a three week ulcer-healing course of lanzoprazole or omeprazole followed, if the patient has to re-start on NSAIDS or aspirin, by maintenance therapy.

Helicobacter pylori infection and bleeding peptic ulcers

About 60–70% of all gastric ulcers and 80% or more of all duodenal ulcers are caused by H. pylori infection within the stomach (most of the remainder are associated with use of NSAIDs). Eradication of the infection speeds ulcer healing and, of importance to the Acute Medical Unit, if the ulcer has bled, eradication lessens the risk of re-bleeding. Eradication therapy is simple – a week of ampicillin, omeprazole and clarithromycin – and should be started once the patient returns from endoscopy if the patient has a duodenal ulcer and tests on the endoscopic specimens are H. pylori positive. This aspect of management is frequently neglected. The situation with bleeding gastric ulcers is more controversial and in most cases re-endoscopy is advisable 6 weeks after the initial bleed, at which time tests for H. pylori can be performed and eradication therapy given if necessary.

Acute gastritis, duodenitis and acute erosions (‘stress ulcers’)

Acute gastric and duodenal erosions are common in patients taking NSAIDs and aspirin. Although they can cause massive blood loss, the bleeding will stop provided the patient survives the initial event. The two major issues are adequate resuscitation and ensuring that the blood loss is not arising from a more serious source such as a chronic ulcer or varices.

Mallory-Weiss tear

Acute oesophageal mucosal tears can be diagnosed from the history: patients retch and vomit several times before noticing that one of their vomits contains a varying amount of fresh blood. The patients are usually young, and acute alcohol intake is often involved. The bleeding can be heavy and the patients can be very alarmed. The outlook is almost universally excellent, with the bleeding stopping of its own accord and the tear healing completely within 24h.

Oesophageal varices

Less common, but more frightening for everyone concerned, oesophageal varices account for around 10% of acute bleeds. Blood loss can be massive and can itself result in death, but more commonly it triggers acute liver failure – in patients whose livers are already performing badly. Varices need active intervention to stop them bleeding and to reduce the risk of a re-bleed. Overall death rates are high, up to 30%. Fortunately, there have been important improvements in the field using endoscopic (injection sclerotherapy and banding) and radiological (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic anastomosis) techniques. It is to the general relief of many that the Sengstaken tube is now making progressively fewer appearances on the medical ward.

Gastric and oesophageal cancer

Gastric and oesophageal cancer occur in older patients, and the bleeding is often preceded by a history of weight loss, anorexia and, in the case of oesophageal cancer, swallowing difficulty.

Dieulafoy’s erosion

This rare cause of massive bleeding is due to erosion of a congenitally abnormal artery in the lining of the stomach. Emergency surgery is often required.

Management of Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage

Ensuring the safety of the patient: ABCDE

The consciousness level may be impaired, either as part of shock (poor cerebral blood supply) or because the bleeding has occurred in a patient with liver disease and has triggered liver failure. However, unless the bleeding has taken place, say, as a stress reaction to an acute stroke, the airway is unlikely to be at risk.

Administer high-flow oxygen immediately if the patient is hypotensive or has a pulse over 100 beats/min – on the assumption there has been a major bleed. Monitor the oxygen saturations to assess the response.

Check the patient for any pain: severe abdominal pain is unusual in upper gastrointestinal bleeding and needs urgent medical assessment. In the elderly, blood loss can readily trigger an anginal attack or even cause myocardial infarction.

Anticipate that large-bore i.v. cannulae (e.g. grey Venflons®) will be inserted into both arms and that either immediate saline or polygeline (Haemaccel®) may be needed. If there is haemodynamic disturbance (e.g. pulse 110 beats/min, systolic blood pressure 100mmHg, respiratory rate 30 breaths/min), it would be appropriate to give 2L of isotonic saline rapidly and then, if there is no improvement, consider polygeline (Haemaccel®), as at least 20% of the blood volume will have been lost.

Who needs urgent endoscopy?

Young patients with minor gastrointestinal bleeding in whom there is no change in pulse or blood pressure can be safely discharged and do not require endoscopy. Most other patients with gastrointestinal bleeding can safely be endoscoped on the next available endoscopy list. Indeed, the risks of emergency endoscopy in an inadequately resuscitated patient in the middle of the night can outweigh the potential advantage. However, urgent endoscopy to establish the site of blood loss, assess the risk of re-bleeding and attempt endoscopic haemostasis is required:

• when oesophageal varices are suspected

• after massive bleeding

• in the high-risk elderly

• when the problem is a re-bleed

Assessing the degree of bleeding

The history is invaluable in assessing blood loss:

• haematemesis with melaena indicates greater bleeding than either alone

• clots in the vomit and recognisable blood in the stool both indicate heavy bleeding

• postural dizziness and overwhelming thirst suggest a major bleed

The examination adds supporting evidence to the history. However, the patient’s age will influence the signs – a young person can lose 500ml or more of blood before any of the observations change, but a similar loss in an elderly person would have a major impact. The patient with major bleeding characteristically:

• is pale and clammy

• has a tachycardia of more than 100 beats/min

• has a systolic blood pressure of less than 100mmHg

• shows postural hypotension, with a 20+ mmHg fall in the systolic pressure on sitting

Assessing the risk to the patient from the bleed (→Case Study 5.1)

Age – is the patient over 60 years of age? The mortality rate in upper gastrointestinal bleeding is 20 times higher in the elderly than in the young:

• the underlying causes are more serious (e.g. gastric ulcers and gastric cancer)

• pre-existing heart disease may complicate the effects of acute blood loss

Case Study 5.1

An 84-year-old independent man presented with two syncopal episodes followed by a large vomit of recognisable blood. He had a 1-week history of upper abdominal pain and was taking regular low-dose aspirin.There was a past history of chronic angina and Type II diabetes.

On admission the patient was pale, alert and orientated with blood visible around the mouth.The pulse was 80 beats/min and the blood pressure 135/65mmHg lying and 80/35mmHg sitting.There was mild epigastric tenderness and rectal examination revealed soft brown stool.

The initial assessment was of an acute upper gastrointestinal bleed in a highrisk elderly man with ischaemic heart disease. Haemaccel®, 2 units, was given while awaiting the first of 6 units of blood that were ordered.The surgeons were contacted and agreed to visit ‘if there was a second bleed’. A central line was inserted.

Three hours after admission the patient vomited 500ml of fresh blood. Emergency endoscopy showed a 1.5-cm deep gastric ulcer.This ulcer was not actively bleeding and was injected with adrenaline (epinephrine).Twenty-four hours later the patient appeared to be stable, having had a total of 5 units of blood. A second endoscopy was ordered by the surgeons and showed a ‘spurting vessel’; this was re-injected.After this the patient’s condition remained stable. Surgery was planned in the event of further bleeding.

Six days after admission the patient had a sudden massive bleed and suffered a cardiac arrest.The patient aspirated blood into the lungs. Resuscitation was unsuccessful and the patient died.

Amount – small, moderate or large? The initial assessment of pulse, blood pressure and direct observation should be interpreted in combination with the results from the endoscopy. Clearly, the finding of ‘a spurting arterial bleed from the base of a chronic gastric ulcer’ is much more significant than ‘no visible blood in the stomach or duodenum’.

Is there another complicating condition present? The three most important diseases that will influence the chances of recovery are:

• liver failure (abnormal clotting, varices, encephalopathy)

• kidney failure (worsened by acute blood loss and reduced renal blood flow)

• heart failure (impairs the corrective responses to blood loss, increases the risks of transfusion)

Is there an underlying malignancy? This may be the direct source of the bleeding, or the bleeding may be from stress ulceration caused indirectly by a malignancy elsewhere. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is quite a common problem in terminal malignant disease.

Risk assessment with the Rockall Score

The Rockall Score is used to distinguish between those patients who can be discharged early without endoscopy and those in whom, without emergency intervention, there is a high risk of re-bleeding and death. Patients are scored before and after endoscopy (→Table 5.1).

| Score 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| age | 60 | 60–79 | 80+ | |

| shock? | Pulse < 100 SBP > 100 | Pulse > 100 SBP > 100 | SBP < 100 | |

| co-morbidity? | nil | CCF, IHD, other major conditions | renal failure, liver failure, metastases | |

| diagnosis | Mallory-Weiss | all other | GI cancer | |

| Endoscopic signs of bleeding | no bleeding | fresh blood, clot, spurting |

When the pre-endoscopy score is 0 it is generally safe to discharge the patient early without urgent endoscopy – a higher score requires early endoscopy. A full (post-endoscopy) score of <3 indicates a low risk of re-bleeding or death and these patients can be considered for accelerated discharge.

Looking for evidence of re-bleeding

There are several endoscopic features that predict a high risk of re-bleeding:

• active arterial bleeding (90% risk)

• a vessel visible at the base of an ulcer (50% risk)

• an adherent clot over an ulcer crater (30% risk)

Features that indicate re-bleeding are fresh haematemesis or melaena associated with disturbed haemodynamics – a pulse rate over 100 beats/min, a systolic pressure less than 100mmHg, a fall in CVP more than 5cmH2O or a fall in haemoglobin of more than 2g in 24h. Depending on the underlying diagnosis, patients who re-bleed will need further endoscopic procedures and, if these are unsuccessful, a second re-bleed will almost certainly lead to emergency surgery. Reliable, well-charted observations are critical in the close monitoring of these patients during the first 48h of their admission. The pulse rate is the single most useful measurement, as it is the first to change if the patient re-bleeds (or remains high if bleeding does not stop in the first place). The drop in blood pressure lags behind the increase in pulse rate, although a postural decrease also provides a useful early warning. Halfhourly observations are needed in the first 4h after an acute bleed.

In major bleeds, the CVP provides the most reliable guide to re-bleeding, because it falls before there is any increase in the pulse rate. It is invaluable in the elderly in whom the risks are high and other factors such as betablocker therapy and cardiac arrhythmias render the pulse rate unreliable as a sign of blood loss (→Case Study 5.2).

Case Study 5.2

An 87-year-old woman was admitted with haematemesis and melaena. Endoscopy showed oesophagitis, pyloric stenosis and a bleeding duodenal ulcer, which was injected, with apparent success. At 01.00h her pulse suddenly increased from 100 to 140 beats/min and her blood pressure fell acutely. There were no external signs of further bleeding. Her ECG showed rapid atrial fibrillation at 140 beats/min. She remained hypotensive for half an hour before she reverted spontaneously to normal rhythm, when her pulse and blood pressure also normalised. She did not re-bleed after admission and made a good recovery. Any acute illness in the elderly can trigger rapid atrial fibrillation, which in itself can lead to a sudden, but reversible, deterioration in the patient’s condition.

The patient described in Case Study 5.1 is typical of the type of patient who is commonly admitted to the acute medical wards. He was at high risk because of:

Many personnel were involved, and the patient needed extremely close monitoring. Characteristically, there was uncertainty over the indications and timing of surgery – in circumstances in which a clear management plan from the outset is a fundamental requirement. An early, combined and well-documented consultation between the physicians, surgeons and nursing staff is invaluable in cases such as this, in which the risks of major complications can be anticipated from the moment the patient is first seen.

While difficult management decisions are being considered, it is also critical that the nurse is focused on the immediate condition of the patient:

• Quarter-hourly observations may be necessary during the first few hours after a massive bleed to determine whether the bleeding has stopped. These can be reinstated at the first sign of re-bleeding (e.g. a fall in a previously stable CVP or a large fresh melaena stool).

• Reassuring signs are a decrease in the pulse rate and reduction in any postural hypotension.

• The respiratory rate is raised in shock, but will also increase if the patient develops pulmonary oedema due to over-transfusion – this is a particular risk in an elderly patient with pre-existing heart disease who has needed vigorous resuscitation with fluids and blood.

Intensive monitoring and urgent investigative procedures are likely to lead to disorientation and distress in these elderly patients. Constant reassurance is needed, combined with careful explanations of the various interventions and staff that the patient is suddenly encountering. It will be a great comfort to the patient to be able to identify at least one familiar face among the frenetic activity of the first 12–24h. Patients with significant blood loss are extremely weak and debilitated. If there is frequent melaena, the effort of calling for, and using, a commode at short notice will be exhausting (and often extremely embarrassing) for the patient. Nursing staff have to be readily available to assist the patient and to deal with the distress of melaena or haematemesis with sensitivity and professionalism.

Intravenous pantoprazole/omeprazole?

High dose i.v. proton pump inhibitors pantoprazole/omeprazole 80mg stat and 8mg per hour for 72 hours are only used in patients who have had a major bleed from a peptic ulcer. Treatment is started after the patient has returned from endoscopic haemostatic therapy.

Role of the nurse in facilitating communication

Case Study 5.3 illustrates how poor communication can affect a patient’s treatment. This was a very high-risk case due to the bleeding source, the age of the patient and the pre-existing health of the patient. There was good early liaison with the surgeons, but the problems arose because of the quality of the communication. An issue as simple as the orientation of an endoscope photograph had serious consequences and underlines the enormous value of effective communication. In this case, it would have been invaluable to have had a senior member of the surgical team present at the endoscopy.

Case Study 5.3

A 71-year-old woman was admitted with major upper gastrointestinal bleeding: there were large fresh clots in her vomit bowl and dark red blood mixed in with melaena. A week before admission an exercise test had been aborted because of early ischaemic changes on her ECG. She had also suffered a myocardial infarction 6 months previously. Emergency endoscopy revealed a typical Dieulafoy anomaly with a visible arterial bleed, high in the lesser curve.

After unsuccessful attempts at endoscopic injection and embolisation she was taken as an emergency to theatre.There was no direct communication between the senior surgeon and the endoscopist; much of the information transfer was either through a third party or from the endoscopy form, which itself was filled out ambiguously. Furthermore the first operation, a partial gastrectomy, was done under adverse conditions with the patient actively bleeding and hypotensive.The lesion was not included in the resected gastric tissue. She continued to bleed after surgery and so further surgery with a total gastrectomy was done. She made an uneventful recovery after this.

The nurse is in an ideal position to facilitate the liaison between surgeons and physicians.

• Are the observations and transfusion charts clearly documented and displayed so that the surgeons can judge whether the patient is still bleeding or is re-bleeding?

• Is the most recent bowel action/vomit available to be seen and documented in the nursing notes?

• Are the most up-to-date blood results available (especially the blood count and clotting studies)? Ideally, they should be displayed on a flow chart.

• Is there an informed member of the medical team (e.g. the endoscopist or the registrar) available on the ward?

• Are the case notes available and, most importantly, is the endoscopy record available?

• Does the patient understand why a surgeon has been involved?

• Has an ECG been performed and seen by the medical team?

▪ Following an established management protocol based on national guidelines

▪ Intensive nursing input during the initial period of instability

▪ Clear guidelines for the changes in observations to be reported to medical staff

▪ Combined medical and surgical input in high-risk patients

▪ Use of central venous lines in high-risk patients

▪ Good liaison with the gastroenterology team

▪ Access to early endoscopy and endoscopic haemostatic techniques

▪ Appropriate monitoring, including clotting studies in all high-risk patients

▪ Patients for emergency surgery to see the senior surgeon preoperatively

Answering Relatives’ Questions in Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

How serious is the bleeding? The answer depends on the patient. Although the average mortality risk from upper gastrointestinal bleeding is 10%, it varies by a factor of 20 between the young and the elderly, and from extremely low rates in acute gastritis to perhaps 20–30% in acute bleeding varices.

Will the ulcer stop bleeding of its own accord? Eight out of ten ulcers stop bleeding on their own; the rest are treated at endoscopy with injection or coagulation. In these cases nine out of ten will stop bleeding, but a very small number will need to go on to urgent surgery, either because the procedure does not work or because it is only temporarily successful.

How will the endoscope examination help? It will tell us the cause of the bleeding and will give some idea if it will stop. Heavy bleeding from an artery, for example, is more likely to need surgery than a superficial area of inflammation in the gullet. It may be necessary to try and seal off the bleeding at the time of the examination, using locally applied heat or an injection into the bleeding point.

What is the outlook in bleeding from oesophageal varices? Although treatments have improved greatly in recent years, this remains a very serious condition. Much will depend on whether the bleeding can be stopped and, if it can, whether there is further bleeding in the first 2–3 days. About a fifth of all patients who bleed from varices re-bleed in the first few days, and for them the outlook is not particularly good.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree