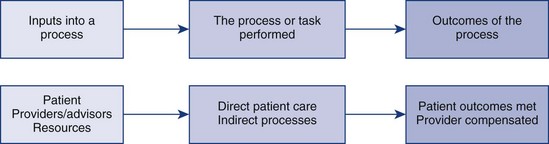

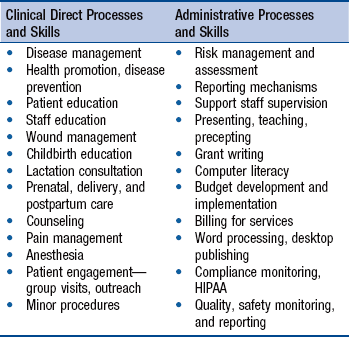

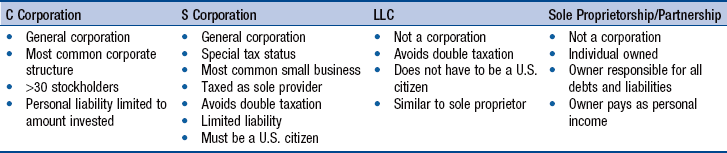

Chapter 19 Principles of Practice Management Day to Day Administrative Support Program and Business Structure Evaluation Processes That Ensure Quality and Safety Health Care Payment Mechanisms Evolving Business Opportunities for Advanced Practice Nurses By virtue of their expanded knowledge and skill set built on a nursing framework, advanced practice nurses (APNs) are uniquely poised as effective alternatives to the traditional physician provider. Several factors in the national health care arena have coalesced to place APNs in an excellent position to offer direct care to their patients. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report, The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health (2011), opened the door to remove barriers that impede APNs from practicing at the full scope of their knowledge and skill. The IOM report, coupled with the nursing and patient initiatives in the Patient Protection and Accountable Care Act (PPACA; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2011) and the unfolding regulatory changes made possible by the Consensus Model for APRN Regulation (National Council of State Boards of Nursing [NCSBN], 2012), have made it possible for APNs to practice in more broad-based venues than ever before. Also, doctoral education assists APNs in achieving the direct and indirect goals of care by enhancing their ability to design and deliver effective care (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2006). Enhanced leadership, policymaking, and collaboration skills will augment their ability to make positive change at the system and practice setting levels. The goal of this chapter is to prepare APN graduates for the business components of practice as owners of their own practice or as employees or contractors of service in the health care field. One particular innovation in patient care settings that has been successful over time is the conceptualization and organization of the direct and indirect processes of patient care within the context of systems thinking (Colbert & Ogden, 2011; Reel & Abraham, 2007; Solberg, Kottke, Brekke, et al., 2000; Story, 2010). Simply put, any system represents the flow of resources through a process that results in the desired outcomes (Fig. 19-1). The size and complexity of the developed system depends on the number and complexity of processes being used to attain the desired outcome. Evaluation of any system includes assessment and evaluation of the resources used, processes used, and outcomes attained. One recent innovation to assist in this process is the health care dashboard (see later). Success in and satisfaction with one’s APN role revolves around the right match between APNs and the work they do and the ability to be flexible and innovative within the scope of that role. APNs’ adaptability to the changing health care marketplace is one of their greatest strengths. As noted, APNs participate in direct and indirect care processes in any practice setting. Indirect processes include the steps taken to market the practice, register a patient, and collect demographics, the process of third-party billing, meeting regulatory, safety, and quality imperatives, and the interaction with medical, pharmaceutical, and office supply vendors. Table 19-1 lists examples of clinical and administrative processes and skills. Direct and indirect processes are essential to the successful management of any health care system, whether it is a small, self-contained APN practice, a physician practice, or a large multihospital network. It is important to note the differences between the direct and indirect care of patients described in Chapter 7 and the discussion here of direct and indirect processes of practice. For example, in this chapter, quality and risk management are included as direct processes, but the management and reporting of these activities are indirect processes. Over an APN’s career, the balance between direct and indirect process involvement and the size of the system in which these processes occur may vary. At any given time, such shifts in balance and size of the system may require that APNs adopt an entrepreneurial approach, intrapreneurial approach, or mixture of both (Dayhoff & Moore, 2005; Wilson, Averis, & Walsh (2003). The term entrepreneur refers to someone who plans, organizes, finances, operates, and participates in a new health care delivery organization. Entrepreneurs have control over and responsibility for an increased proportion of indirect processes of care in their roles as compared with intrapreneurs. The term intrapreneur refers to someone who is generally an employee of an existing health care system, in which many of the indirect processes of the care delivery system may be controlled and managed by other employees or departments. The intrapreneur improves, redesigns, or augments an employer’s current direct care processes, with a lesser role in day to day business administrative functions. Entrepreneurs function within the context of the larger, societal health care system. Intrapreneurs function within an institutional health care system—a microcosm of the larger arena. Both entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs are risk takers; however, entrepreneurs are likely to take bigger risks and have a higher tolerance for the accompanying uncertainty. Entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs are individuals who continually search for and are receptive to opportunities and innovation. Innovation comes through the creation of a new process—direct, indirect, or both—or through radical changes to an existing process so that it seems like new. Philosophical and theoretical bases for practice: • What type of nursing practice or approach to care delivery best describes how I perceive my own nursing practice? • What do I value most, and how does that value get expressed in my practice? • Do my options favor this model or some other approach? • If they favor another approach, how compatible is it with my own beliefs and values? (See Chapter 2.) Preference for intrapreneurial or entrepreneurial approach: • Do I thrive on risk taking, like some risk, or prefer situations with a conservative level of risk involved? • How is a “loss” or being “unsuccessful” defined? • If I like taking risks, how much of a loss can I afford to take—professionally and personally—if my venture proves to be unsuccessful? (The more risk one is willing to take, the more entrepreneurial one is likely to be.) • Do I prefer being part of a team or being on my own? • If I like being on a team, what other team members would I like to be included on this team? • How big a team am I most comfortable with? • If I prefer working on my own, how will I interact with my colleagues? (See Chapters 7, 9, and 12.) A skills inventory can serve as a springboard for the clarification of the APN’s professional goals. The extent to which the APN balances the clinical role with administrative demands depends on the APN’s skills and preferences and begins with an inventory of those clinical skills and administrative talents that the APN would like to bring, or acquire, in an ideal advanced practice role. Box 19-1 lists some questions that may refine one’s ideal inventory. The questions in Box 19-1 are among the many questions to be answered by APNs before deciding how extensive their role will be in the management of their program or practice. Fortunately, several resources help clinicians better understand the indirect processes, or business, of clinical practice. The reader is referred to Buppert (2012a) for an in-depth discussion of nurse practitioner (NP) business and legal concerns. In 2012, the American Medical Association (AMA) launched a new web-based practice management center (AMA, 2012b) to support physicians in the business management of their practices, which is also useful to APNs. Entrepreneur and other business magazines provide useful information related to business management and administration. The Small Business Administration (SBA; www.sba.gov) provides general and specific information regarding business management and referral to local supports, including the local office of the Service Corps of Retired Executives (SCORE; www.score.org/business_toolbox.html). There are many other online resources related to business management. Specific websites that may be useful to the development of small businesses include the following: • www.americanexpress.com (American Express Company, 2012). Go to “Open small business” to find advice about business start-up and community networking. • www.entrepreneur.com. This website offers information about a wide variety of issues regarding financing, technology, and business opportunities. • www.dol.gov/osbp. The Department of Labor, Office of Small Business Programs, offers good information about minority- and women-owned businesses. • www.learn.gwumc.edu/hscidist/practice/home/weblinks.htm. This website offers a substantial list of links that support practice business management issues. • http://barbaracphillips/home/np/promotion. This website offers resources on marketing an APN practice or employment. • www.health caresuccess.com. This website offers health care success strategies, resources for profitable growth. • www.score.org/resources. This website offers information about the SCORE association business counseling. • www.webNPonline.com. This website offers “Practice Management: A Business Guide for Nurse Practitioners.” Direct care of patients and families is the central competency for APNs (see Chapters 3 and 7). The direct process of care for a given practice or practice population is defined as those patients who will receive direct clinical care by the APN in a practice environment. High-quality care and patient satisfaction sustain any level or configuration of practice over time. The patient population served, components of care and procedures based on the APN role, scope of practice, and mission must be carefully considered before implementing care. Ongoing evaluation with regard to patient outcomes and patient satisfaction is an important tool to maintain high-quality, safe care over time. The therapeutic relationships that are the trademark of APN direct practice provide opportunities for innovative business opportunities (Person & Finch, 2009; Thomas, Finch, Schoenhofer, et al., 2005). One way to think about practice environments is that they represent small health care systems based on a patient population with identified needs. This patient population is identified through a variety of means, including individual APN expertise and preference based on the role and scope of practice of the individual APN. For certified nurse-midwives (CNMs) and certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs), the patient population is essentially defined by their roles with childbearing women and their families and with patients undergoing surgical anesthesia, respectively. NPs and clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) have a broader population base (e.g., family NP, psychiatric CNS; see Part III). Sometimes, APNs identify patient populations through other modifiers, such as age, health promotion specialty, or disease state specialty (e.g., CNMs who care for adolescent mothers-to-be, CRNAs who specialize in providing anesthesia in pain management centers, and adult NPs or CNSs who specialize in the management of asthma or diabetes). In other cases, it is the geographic location or organizational setting that differentiates one’s patient population of interest. Examples of these populations are the rural underserved populations cared for by National Health Service Corps providers, veterans cared for in Veterans Affairs Medical Centers, and those in the newly designated accountable care organizations (ACOs; see Chapter 22). APNs must be able to define the patient populations they are serving in their clinical practice clearly and succinctly. After the patient population has been identified and the patient care processes have been outlined, the APN will need to formalize this information in a mission and vision statement. This is where APNs differentiate their practices from physician practices using the nursing model of care and nursing attributes. The mission and vision statement describe to patients and prospective funding agencies the APN practice’s reason for existence and future direction; this brief statement serves to remind the APN entrepreneur about where the program or practice’s priorities should lie. Professional values include those tenets of nursing practice that provide significance and meaning to the APN’s practice of nursing (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2001; Sellman, 2011). The mission and goal statements of national APN organizations clearly portray these values as well. One’s professional and personal values influence one’s comfort with risk taking and preference about the arena in which care is delivered. The written summary of program or practice values may be combined with the mission and vision statement into one document, such as a brochure or program information sheet. This summary is available for review by any interested party and should be given to every patient at the time of the first practice encounter. These values must be held by all staff, especially those who come into direct contact with patients. As a business owner, it is important for the APN to create a culture of caring and holism throughout the organization. The mission states the goal of the direct processes of care in one sentence—for example, “comprehensive primary care and wellness care for pediatric and adult individuals and families.” This can be distilled into a tag line, such as “innovative health care” (see Chapter 20). The vision statement describes the ideal 5-year goal (i.e., what the APN envisions the clinical care to be 5 years from inception). The mission and vision statements should enhance transparency and interdisciplinary collaboration as APNs clearly articulate their values, goals, and vision of patient care to existing and potential colleagues, consultants, and third-party payers. If the APN is functioning through an intrapreneurial approach as an employee, the organization’s mission and vision should be carefully examined to ensure that the practice or program fits into the overall goals of the organization and into the APN’s personal goals. If the program’s mission conflicts with that of the organization, problems may take the form of delays in funding, changes to the program’s direct or indirect processes of care, barriers to program implementation, and outright denial of program development. If other providers, individuals, or groups have a stake in the program, the mission and vision statement should be determined through consensus of the group (see Chapter 20 and SCORE [www.score.org/business _toolbox.html]). Privacy and confidentiality are important ethical issues that require careful consideration. The balance between the patient’s right to privacy and society’s need to be protected is important. State laws clearly explicate those patient issues, such as sexually transmitted diseases, abuse, or tuberculosis, that are reportable by law. Patient confidentiality is critical to the provider-patient relationship. Other than legal reporting obligations, it is the patient’s right to decide which information the APN and all other members of the health care team may share with others. The federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) became law in 1996. Mandatory compliance with federal regulations began in 2003. HIPAA mandates the proper use and disclosure of personal health information. APN business owners and providers must have policies and trained personnel in place to implement privacy standards (Buppert, 2012b). An APN employee must also be knowledgeable about office policy and all HIPAA compliance regulations. HIPAA guidelines are detailed on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) website (2012a). This site provides a good overview of the privacy rule, current updates related to electronic records, and answers to frequently asked questions about implementation. The APN must advocate for measures that improve quality, safety, and security in the office environment and that provide a sense of well-being for staff, patients, and their families. An important component of any health care practice endeavor is a commitment to high-quality care (Barkauskas, Pohl, Tanner, et al., 2011; Johnson, Harper, Hanson, et al., 2007; Muller, Hujcs, Dubendorf, et al., 2010). Measures to ensure quality outcomes should be in place. Title III of the PPACA (HHS, 2011) defines initiatives that pertain to quality health care. Several resources found online (www.ncqa.org; www.naqc.org and www.nationalforum.com) can help APNs set a quality agenda (see Chapters 22 and 24). Safety policies should clearly articulate how to maintain patient, provider, and staff safety, including provisions for securing a patient’s valuables during procedures and for managing hostile persons in the area, including a policy for managing violent and armed persons. The waiting room door should be locked to the patient care area. Adequate lighting, railings, and paved walkways are necessary, as well as adequate parking close to the facility. The level of security needed depends on the APN’s practice environment, knowledge of staff about patients’ conditions and potential safety issues, and available resources within the facility (see www.qsen.org and Chapters 22 and 24). Each practice must adhere to Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) guidelines (www.OSHA.gov). One employee should be designated as an OSHA officer. Ethical clinical practice demands honesty and integrity in all patient interactions. Under the best circumstances, communication lines will be open and the APN and patient will understand each other and feel as if they have been understood. When misunderstandings occur, the APN should manage the issue as if it were a patient complaint, seeking to address the concerns in an objective and timely manner. Risk management policies and protocols must be enacted to ensure that timely and thorough communication is delivered to the patient regarding all visit outcomes, plans of care, and diagnostic test results (Cox, 2010; Hall, 2010). This is of vital importance to the legal and ethical success and safety of the APN practice. Dealing with difficult and noncompliant patients requires a distinct skill set, experience, and understanding. Over time, many issues can be resolved between the patient and caregiver with a skillful APN who is knowledgeable about appropriate interventions for resistance and the stages of change. If termination of the provider-patient relationship is necessary, this may be accomplished in many ways. It is important to provide alternatives for another provider so that the patient does not feel abandoned. Finally, whatever rules the APN practice has set as grounds for termination of this relationship must be in writing, well-documented, and sent to the patient as a certified, return receipt letter. Resolving complaints is not usually an ethical issue; however, it is good business practice to monitor patient satisfaction with the clinical experience from the time that the patient enters the waiting room until the final bill for services is paid. Many valid, reliable patient satisfaction tools are available to health care providers to measure patients’ responses to how care is delivered (Kleinpell, 2001; Tingle, 2011; see www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov). Despite one’s best efforts, however, patients may be dissatisfied with some aspect of their experience at some point during an APN’s career. It is important that any patient’s complaint or sign of dissatisfaction be addressed immediately, preferably at the time of the complaint (Buppert, 2012a). A formal policy related to the management of patient complaints includes how patient complaints are recorded, who investigates and responds to the patient’s concerns, and how quickly the complaint is addressed. Specific guidelines for managing patient complaints may be supplemented by risk management information provided by the APN’s malpractice carrier. Although the APN is assumed to be the primary provider in this discussion, attention must be paid to the development of clinical relationships with other APNs, physicians, pharmacists, and allied health colleagues. (In-depth discussions related to clinical mentorship, consultation, and collaboration are found in Part II.) To be successful, the APN must maintain a collegial relationship with other health care providers (Clausen, Strohshein, Farem, et al., 2012; Horns, Czaplijski, Endelke, et al., 2007; Lindeke, 2005; Young, Siegal, McCormick, et al., 2011). An important legal consideration is defining the parameters of the association with a collaborating physician. In states that require medical collaboration, it may be through the development of a collaborative practice or contracting agreement. Even without a state statute, strong collegial relationships that provide support and coverage for time off are essential to the success of the APN practice. Also, in APN-owned practices, impediments to care can occur when referring to out of area facilities for diagnostic testing. Although less common than in the past, some facilities want a Doctor of Medicine (MD; physician) as the referring provider to be identified on patient orders and correspondence. In some states, if APNs’ names are not accepted as the primary provider, patient test results may be sent to the collaborating physician, who is off site and unable to prescribe or otherwise care for patients. APNs must be able to track these results to provide adequate safe care for patients; arrangements in which referral specialists do not communicate directly with the referring APN jeopardize safe and responsible patient care. Separate from, but as important as, the clinical advisors and resources described earlier are the administrative advisors and resources required to develop and maintain smooth indirect processes to support patient care. An independent practice will need to contract or consult with an accountant, attorney, banker, and insurance agent for specific services (Buppert, 2012a). In addition, the services of a practice management consultant with medical billing expertise should be enlisted (www.learn.gwumc.edu/hscidist/practice/home/weblinks.htm; Reel & Abraham, 2007). The accountant will assist the APN in setting up an accounting system, establishing internal controls, and preparing an operating budget. She or he will set up the practice to ensure that the best tax advantages and flexibility are obtained (Buppert, 2012a; Burman, 2010). Attorneys with expertise in health care law should establish the legal structure of the practice and provide advice on an as-needed basis for special purposes. It would be best if the attorney and accountant have a working relationship so that the legal structure selected provides the best legal, financial, and tax advantages for the providers involved. The banking relationship serves to establish a line of credit or business loan (if needed) and to meet business banking needs. A business insurance agent provides expertise in the areas of health, liability, and Workers’ Compensation insurance programs. The practice management consultant serves to develop policies and procedures manuals, billing procedures and fee schedules, and job descriptions for an entrepreneurial enterprise (Buppert, 2012a; Letz, 2002; Reel & Abraham, 2007). A medical billing expert provides guidance for the efficient completion and processing of billing forms to receive third-party reimbursement or capitation payment for the provider’s services and for the thorough and accurate completion of any third-party payer’s contracting paperwork required for the APN’s participation in selected contracts. The APN needs to carefully decide which of these functions can be done by the APN–APN practice staff and which need to be purchased as externally contracted services. It is important for the APN entrepreneur to ask himself or herself the following questions: • Is this an area of strength and interest, or is this an area to which I do not want to attend? • Is this an indirect process of care to which I want to devote time and energy? • More importantly, is up-front capital sufficient to sustain the practice until it can generate its own income (usually at least 6 to 12 months)? The organization of day to day administrative support staff services (separate from the services of business advisors) revolves around the processes of care being delivered and the environment in which services are delivered. Once the APN knows what the direct patient care processes will include, and has identified those indirect processes that will support the patient encounter, additional ancillary personnel may be needed. The APN maintains ultimate responsibility for all operations if she or he owns the practice, even if a practice manager is managing daily operations. APN employees must be aware of their specific responsibilities and understand which belong to them and which belong to the owner. In a community-based primary care setting, the practice may require someone to assist in patient registration and scheduling (the first process box in Fig. 19-1), assist the clinician in certain elements of patient care (the second box), and collect or process patient fees (the third box). Any additional administrative roles support these primary roles and may include someone to manage patient medical records and new technologies, such as the electronic health record (EHR) and e-reporting (see Chapter 24), triage acutely ill patients by telephone, and perform office cleaning functions. Those who fill these roles should have skills and qualifications complementary to those of the APN and should be able to meet practice goals for patient care. An organizational chart and job descriptions of the roles required should be developed, placed in a common personnel manual, and shared among staff members so that everyone is aware of his or her role within the successful functioning of the system. At the end of each day, the APN should ensure that all direct and indirect processes of care have been completed. Some practices are now using dashboards to display their practice metrics in a form that is most useful to project quality, cost, and performance (www.dashboards. com). All these factors provide the patient with the most comprehensive health care and the provider with timely and accurate reporting; support services information is completed and insurance companies’ claims for reimbursement are processed. The three basic ways to structure the practice are a sole proprietorship, a partnership, or a corporation (www.irs.gov/business/small/article; Buppert, 2012a). The primary differences among these structures lie in differing tax restrictions and liability. A limited liability company (LLC) is not a corporation but offers many of the same advantages. Many small business owners and entrepreneurs prefer an LLC because it combines the limited liability protection of a corporation with pass-through taxations of a sole proprietorship or partnership (www.activefilings.com). See Table 19-2. Most APN practices are eponymous (named after the owner). However, selecting a name for the practice may be an option worth considering in certain situations. For example, a specific practice name may assist in describing the services offered and reflect the business focus (e.g., “Coastal Cardiac Rehabilitation” suggests a geographic location and type of service). Many professionals use their own name to connote a more personalized service and to promote themselves. Most individual states regulate the selection and registration of business names as part of the registration of the business structure process. The process entails registering the business name, conducting a formal state agency search to ensure that the name is not being used by another business, paying a registration fee, and awaiting the receipt of a formal document confirming assignment of the business name to the APN (www.bizfilings.com). Furthermore, the APN may want to protect his or her business name with a federal service mark or trademark (www.legalzoom.com). An interwoven fabric of regulations and guidelines serves as the basis on which APN professional practice is built and developed (see Chapters 21 and 22 and the individual APN chapters in Part III for an in-depth discussion of APN credentialing and regulation). Federal and state regulations, policies of private insurance companies and, in some cases, local politics determine in which business structures and practice environments an APN may work and obtain reimbursement, and whether this practice is independent or collaborative. Although APN students routinely learn about the importance of the rules and regulations established by many different stakeholders within health care systems, the impact on daily practice may not be appreciated until the student becomes a practicing clinician. The major external regulatory vehicles affecting APN practice include the following: • State and federal statutes pertaining to regulation and credentialing requirements for advanced practice nursing (www.ncsbn.org or www.ncqa.org, or individual state government websites) • Guidelines for health care organizations regarding multiple facets of the management, environment, and delivery of health care established by The Joint Commission (TJC; www.jointcommission.org) • OSHA regulations related to safe working conditions for employees (www.OSHA.gov) • Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) regulations pertaining to laboratory services (http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CLIA/index. html?redirect=/clia) • Patient privacy and confidentiality (www.cms.hhs.gov/hipaa) • CMS regulations pertaining to Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement processes (www.cms.hhs.gov/medicare) • Guidelines and rules from private payers that reimburse care A major component of any APNs practice as an independent APN owner or partner or as part of a larger health care organization requires careful attention to evaluation processes. Chapter 24 offers in-depth guidance and tools that support the skills in which APNs need to have competency as direct care providers or as APN administrators to be able to evaluate care and respond to national and state benchmarks. The use of electronic dashboards as a way to organize data and track measurable indicators of patient care outcomes have positively changed reporting and evaluation techniques in recent years. New systems and processes, almost all electronically driven, allow APNs and others to discern how “fit” their practices are (Richardson, 2008, see Chapter 24). The use of dashboards and other so-called governance score cards make it possible to improve clinical outcomes and patient safety and thus demonstrate the impact of APN care in the hospital (Griffin, Staebler, Muery, et al., 2007; Chandraharan, 2010). Tools such as the Hedis measures are making similar strides in community-based primary care settings (www.ncqa.org). An excellent resource for quality is the Nursing Alliance for Quality Care (www.naqc.org). Samples of risk management guidelines may be obtained through the malpractice insurance carriers or as described by Buppert (2012a). Also, Buppert publishes The Gold Sheet, a monthly newsletter on quality for APNs. TJC (2012) evaluates a health care organization’s system performance in patient-focused (direct) and organizational (indirect) care areas to improve the quality of care provided to the public. Patient-focused functions include patient rights and organizational ethics, assessment of patients, care of patients, education, and continuum of care. Organizational functions include improving organization performance, leadership, management of the environment of care, management of human resources, management of information, and surveillance, prevention, and control of infection. In addition, TJC examines an organization’s governance, management, and functions related to medical and nursing staff. Surveys are conducted every 3 years by TJC-employed provider and nonprovider survey teams. An overall score is determined, along with any recommendations for improving scoring deficiencies. Accreditation is based on the organization’s compliance with TJC guidelines and implementation of any recommendations to resolve deficiencies (TJC, 2012). Health care safety management and hazard control are proven processes that produce results by preventing accidents, reducing injury rates, and increasing organizational efficiency (www.OSHA.gov). Topics include emergency planning and fire safety, general and physical plant safety, managing hazardous materials, managing biologic waste, safety in patient care areas, and health care support area safety. In terms of external regulators, safety management is carefully scrutinized by both TJC and OSHA. APNs functioning as entrepreneurs or employers must be well-versed in the rules, regulations, and implementation of safety programs governing these areas of safety management and hazard control, especially with respect to the management of biologic waste and OSHA guidelines regarding bloodborne pathogens. Created as part of the Department of Labor, OSHA was charged by the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 to ensure safe and healthful working conditions for U.S. workers. In 2002, Congress amended OSHA to expand research on the “health and safety of workers who are at risk for bioterrorist threats or attacks in the workplace” (OSHA, 2012).

Business Planning and Reimbursement Mechanisms

Principles of Practice Management

Designing and Delivering Care to Patients

Entrepreneurs and Intrapreneurs

Inventory of Skills

Direct Processes of Care

Direct Patient Care

Mission, Vision, and Values

Compliance with the Health Insurance Portability Accountability Act

Quality, Safety and Security

Risk Management

Resolution of Complaints

Clinical Relationships with Other Staff and Providers

Indirect Processes of Care

Business Relationships

Hiring Business Experts

Day to Day Administrative Support

Program and Business Structure

Titling the Practice

External Regulatory Bodies

Evaluation Processes That Ensure Quality and Safety

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access