Chapter 13

Building an Evidence-Based Nursing Practice

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

1. Identify the benefits and barriers related to evidence-based practice in nursing.

2. Critically appraise systematic reviews, meta-analyses, meta-syntheses, and mixed-methods systematic reviews of current research evidence.

3. Use the PICOS format to formulate clinical questions to identify evidence for use in practice.

4. Describe the models used to promote evidence-based practice in nursing.

5. Apply the Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice for implementing evidence-based changes in your practice.

6. Implement research-based protocols, algorithms, and policies in your practice.

7. Apply the Grove Model to implement national evidence-based guidelines in your practice.

8. Describe the significance of evidence-based practice centers and translational research in developing evidence-based health care.

Best research evidence, p. 415

Duplicate publication bias, p. 433

Evidence-based guidelines, p. 453

Evidence-based practice (EBP), p. 415

Evidence-based practice centers (EPCs), p. 460

Grove Model for Implementing Evidence-Based Guidelines in Practice, p. 456

Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice, p. 450

Location bias of studies, p. 433

Mixed-methods systematic review, p. 441

Outcome reporting bias, p. 433

Research-based protocols, p. 450

Risk ratio (RR) or relative risk, p. 435

Standardized mean difference (SMD), p. 435

Stetler Model of Research Utilization to Facilitate Evidence-Based Practice, p. 447

Phase III: Comparative Evaluation/Decision Making, p. 448

Phase IV: Translation/Application, p. 449

Time lag bias of studies, p. 433

Research evidence has greatly expanded over the last 30 years as numerous quality studies in nursing, medicine, and other healthcare disciplines have been conducted and disseminated. These studies are commonly communicated via conferences, journals, and the Internet. The expectations of society and the goals of healthcare systems are the delivery of quality, safe, cost-effective health care to patients, families, and communities, nationally and internationally. To ensure the delivery of quality health care, the care must be based on the current best research evidence available. Healthcare agencies are emphasizing the delivery of evidence-based health care, and nurses and physicians are focused on evidence-based practice (EBP). With the emphasis on EBP over the last 2 decades, outcomes have improved for patients, healthcare providers, and healthcare agencies (Brown, 2014; Craig & Smyth, 2012; Doran, 2011; Higgins & Green, 2008; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011).

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is an important theme in this text that was defined in Chapter 1 as the conscientious integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values and needs in the delivery of quality, safe, cost-effective health care (Craig & Smyth, 2012; Institute of Medicine, 2001; Sackett, Straus, Richardson, Rosenberg, & Haynes, 2000). Best research evidence is produced by the conduct and synthesis of numerous high-quality studies in a selected health-related area. The concept of best research evidence was described in Chapter 1, and the processes for synthesizing research evidence (systematic review, meta-analysis, meta-synthesis, and mixed-methods systematic review) were defined.

Benefits and Barriers Related to Evidence-Based Nursing Practice

Benefits of Evidence-Based Nursing Practice

The greatest benefits of EBP are improved outcomes for patients, providers, and healthcare agencies. Organizations and agencies nationally and internationally have promoted the synthesis of the best research evidence in thousands of healthcare areas by teams of expert researchers and clinicians. These research syntheses, such as systematic reviews and meta-analyses, have provided the basis for developing strong evidence-based guidelines for practice. These guidelines identify the best treatment plan, or gold standard, for patient care in a selected area to promote quality health outcomes. Students and clinical nurses have easy access to numerous evidence-based guidelines to assist them in making the best clinical decisions for their patients. These evidence-based syntheses and guidelines are found in presentations and publications and can be easily accessed online through the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC, 2014a) in the United States (http://www.guideline.gov/browse/by-topic.aspx), the Cochrane Collaboration (2014) in England (http://www.cochrane.org/cochrane-reviews), and the Joanna Briggs Institute (2014) in Australia (http://www.joannabriggs.org/index.html). Additional EBP resources are presented later in this chapter.

Healthcare agencies are highly supportive of EBP because it promotes quality, cost-effective care for patients and families and meets accreditation requirements. The Joint Commission (2014) revised their accreditation criteria to emphasize patient care quality achieved through EBP. Approximately 25% of chief nursing officers (CNOs) identified the movement toward evidence-based nursing practice as their number one priority (Nurse Executive Center, 2005).

Many CNOs and healthcare agencies are trying to obtain or maintain Magnet status, which documents the excellence of nursing care in an agency. Approval for Magnet status is obtained through the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC). The national and international healthcare agencies that currently have Magnet status can be viewed online at the ANCC (2014) website (http://www.nursecredentialing.org/Magnet/FindaMagnetFacility.aspx). The Magnet Recognition Program recognizes EBP as a way to improve the quality of patient care and revitalize the nursing environment. Selection criteria for Magnet status that require healthcare agencies to promote the conduct of research and use of research evidence in practice follow.

Force 6: Quality Care

“Research and Evidence-Based Practice

These selection criteria include critical elements for EBP, especially financial support for and outcomes related to research activities. Important research-related outcomes to be documented by agencies for Magnet status include nursing studies conducted and professional publications and presentations by nurses. For each study, the title of the study, principal investigator or investigators, role of nurses in the study, and study status need to be documented (Horstman & Fanning, 2010).

The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN, 2013) project was implemented to improve prelicensure nurses’ “knowledge, skills, and attitudes (KSAs) that are necessary to continuously improve the quality and safety of the healthcare systems within which they work.” QSEN competencies were developed in six areas essential for students and registered nurses’ (RNs) practice—patient-centered care, teamwork and collaboration, EBP, quality improvement (QI), safety, and informatics. QSEN competencies were introduced in Chapter 1 and are linked to study findings in all chapters in this text. You can view the competencies on the QSEN Institute website (http://qsen.org/competencies/pre-licensure-ksas). EBP is an important area in your prelicensure education, and educators and students need to work toward achieving the following EBP competencies:

“Participate effectively in appropriate data collection and other research activities.

Adhere to Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidelines.

Base individualized care plan on patient values, clinical expertise, and evidence.

Read original research and evidence reports related to area of practice.

Locate evidence reports related to clinical practice topics and guidelines.

Consult with clinical experts before deciding to deviate from evidence-based protocols.”

Students and RNs demonstrating these EBP competencies are able to provide quality, safe care to patients and to accomplish the goals outlined for Magnet status. Sherwood and Barnsteiner (2012) provide details on the QSEN competencies and educational experiences to promote the KSAs of prelicensure and graduate nurses. In working toward EBP, students and practicing nurses are encouraged to embrace the benefits of EBP; critically appraise current research evidence; refine agency protocols, algorithms or clinical decision trees, and policies based on current research; use the evidence-based guidelines available; and collect data as needed for research projects.

Barriers to Evidence-Based Nursing Practice

Barriers to the EBP movement have been practical and conceptual. One of the most serious barriers is the lack of research evidence available regarding the effectiveness of many nursing interventions. EBP requires synthesizing research evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and other types of intervention studies, and these types of studies are still limited in nursing. Mantzoukas (2009) reviewed the research evidence in 10 high-impact nursing journals, including Nursing Research, Research in Nursing & Health, Western Journal of Nursing Research, Journal of Nursing Scholarship, and Advances in Nursing Science, between 2000 and 2006 and found that the studies were 7% experimental, 6% quasi-experimental, and 39% nonexperimental. However, RCTs and quasi-experimental studies conducted to determine the effectiveness of nursing interventions did increase during that time period.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted in nursing are limited when compared with other disciplines, such as medicine and psychology. In addition, nurse authors of these research syntheses have sometimes indicated that there is inadequate research evidence to support using certain nursing interventions in practice (Craig & Smyth, 2012; Mantzoukas, 2009). Bolton, Donaldson, Rutledge, Bennett, and Brown (2007, p. 123S) conducted a review of “systematic/integrative reviews and meta-analyses on nursing interventions and patient outcomes in acute care settings.” Their literature search covered 1999 to 2005 and identified 4000 systematic-integrative reviews and 500 meta-analyses covering the following seven topics selected by the authors—staffing, caregivers, incontinence, care of older adults, symptom management, pressure ulcer prevention and treatment, and developmental care of neonates and infants. The authors found a limited association between nursing interventions and processes and patient outcomes in acute care settings, as indicated by the following:

Extensive evidence has been generated through nursing research, but additional studies are needed that focus on determining the effectiveness of nursing interventions on patient outcomes (Bolton et al., 2007; Doran, 2011; Mantzoukas, 2009). Identifying the areas in which research evidence is lacking is an important first step in developing the evidence needed for practice. Well-designed experimental and quasi-experimental studies are needed to test selected nursing interventions and to use that understanding to generate sound evidence for practice. Nurses also need to be more active in conducting quality syntheses (systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses) of research evidence in selected areas (Finfgeld-Connett, 2010; Higgins & Green, 2008; Moore, 2012; Rew, 2011).

Another concern is that the research evidence is generated based on population data and then is applied in practice to individual patients. Sometimes it is difficult to transfer research knowledge to individual patients, who respond in unique ways or have unique needs. More work is needed to promote the use of evidence-based guidelines with individual patients. The National Institutes of Health (NIH, 2012) is supporting translational research to improve the use of research evidence with different patient populations in various settings. Patients who have poor outcomes when managed according to an evidence-based guideline need to be reported and, if possible, their circumstances should be published as a case study. Electronic health records (EHRs) now make it possible to determine patient outcomes of care that have been delivered using EBP guidelines.

Another serious barrier is that some healthcare agencies and administrators do not provide the resources necessary for nurses to implement EBP. Their lack of support might include the following: (1) inadequate access to research journals and other sources of synthesized research findings and evidence-based guidelines; (2) inadequate knowledge on how to implement evidence-based changes in practice; (3) heavy workload, with limited time to make research-based changes in practice; (4) limited authority to change patient care based on research findings; (5) limited support from nursing administrators or medical staff to make evidence-based changes in practice; (6) limited funds to support research projects and research-based changes in practice; and (7) minimal rewards for providing evidence-based care to patients and families (Butler, 2011; Eizenberg, 2010; Straka, Brandt, & Brytus, 2013). The success of EBP is determined by all involved, including healthcare agencies, administrators, nurses, physicians, and other healthcare professionals. We all need to take an active role in ensuring that the health care provided to patients and families is based on the best research available.

Searching for Evidence-Based Sources

EBP requires searching a variety of databases and websites for the best research evidence for use in practice. You can identify research syntheses such as systematic reviews, meta-analyses, meta-syntheses, and mixed-methods systematic reviews through searches of electronic databases, national library sites, EBP organizations, and professional organizations. Some of the key resources for EBP are identified in Table 13-1. At least 2500 new systematic reviews are reported in English and indexed in MEDLINE each year (Liberati, Altman, Tetzlaff, Mulrow, Gotzsche, Ioannidis, et al., 2009). The Cochrane Collaboration library of systematic reviews is an excellent resource, with more than 11,000 entries relevant to nursing and health care (http://www.cochrane.org/cochrane-reviews). In 2009, the Cochrane Nursing Care Field (CNCF) was developed to support the conduct, dissemination, and use of systematic reviews in nursing. The Joanna Briggs Institute also provides resources for locating and conducting research syntheses in nursing (see Table 13-1). Chapter 6 provides additional direction for searching electronic databases for individual studies and research syntheses. Once you have identified research syntheses of interest, you need to appraise these sources critically for relevant research evidence for use in your practice.

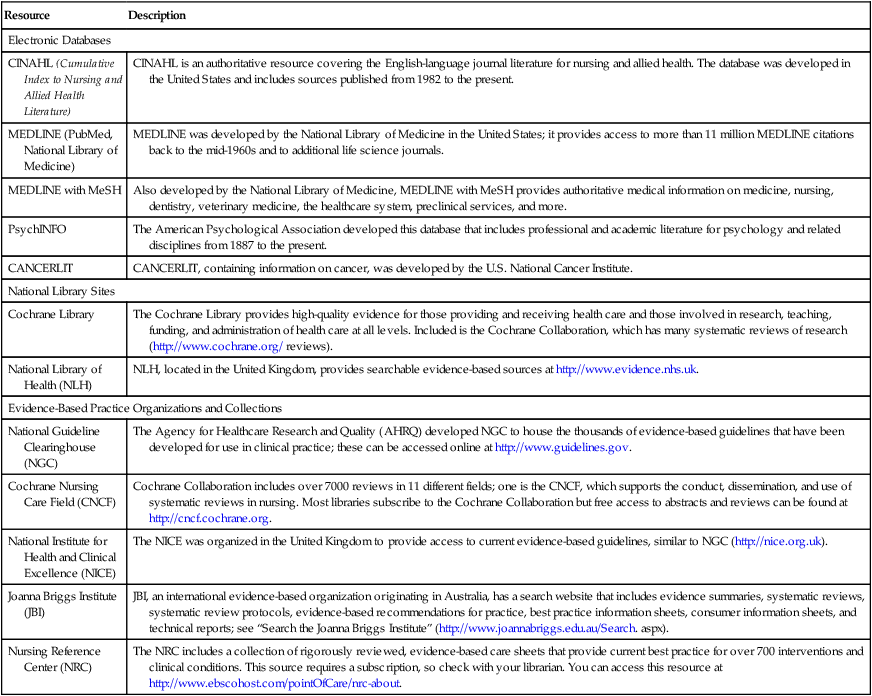

Table 13-1

Evidence-Based Practice Resources

| Resource | Description |

| Electronic Databases | |

| CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) | CINAHL is an authoritative resource covering the English-language journal literature for nursing and allied health. The database was developed in the United States and includes sources published from 1982 to the present. |

| MEDLINE (PubMed, National Library of Medicine) | MEDLINE was developed by the National Library of Medicine in the United States; it provides access to more than 11 million MEDLINE citations back to the mid-1960s and to additional life science journals. |

| MEDLINE with MeSH | Also developed by the National Library of Medicine, MEDLINE with MeSH provides authoritative medical information on medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, the healthcare system, preclinical services, and more. |

| PsychINFO | The American Psychological Association developed this database that includes professional and academic literature for psychology and related disciplines from 1887 to the present. |

| CANCERLIT | CANCERLIT, containing information on cancer, was developed by the U.S. National Cancer Institute. |

| National Library Sites | |

| Cochrane Library | The Cochrane Library provides high-quality evidence for those providing and receiving health care and those involved in research, teaching, funding, and administration of health care at all levels. Included is the Cochrane Collaboration, which has many systematic reviews of research (http://www.cochrane.org/ reviews). |

| National Library of Health (NLH) | NLH, located in the United Kingdom, provides searchable evidence-based sources at http://www.evidence.nhs.uk. |

| Evidence-Based Practice Organizations and Collections | |

| National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC) | The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) developed NGC to house the thousands of evidence-based guidelines that have been developed for use in clinical practice; these can be accessed online at http://www.guidelines.gov. |

| Cochrane Nursing Care Field (CNCF) | Cochrane Collaboration includes over 7000 reviews in 11 different fields; one is the CNCF, which supports the conduct, dissemination, and use of systematic reviews in nursing. Most libraries subscribe to the Cochrane Collaboration but free access to abstracts and reviews can be found at http://cncf.cochrane.org. |

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) | The NICE was organized in the United Kingdom to provide access to current evidence-based guidelines, similar to NGC (http://nice.org.uk). |

| Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) | JBI, an international evidence-based organization originating in Australia, has a search website that includes evidence summaries, systematic reviews, systematic review protocols, evidence-based recommendations for practice, best practice information sheets, consumer information sheets, and technical reports; see “Search the Joanna Briggs Institute” (http://www.joannabriggs.edu.au/Search. aspx). |

| Nursing Reference Center (NRC) | The NRC includes a collection of rigorously reviewed, evidence-based care sheets that provide current best practice for over 700 interventions and clinical conditions. This source requires a subscription, so check with your librarian. You can access this resource at http://www.ebscohost.com/pointOfCare/nrc-about. |

Critically Appraising Research Syntheses

Research evidence is usually synthesized using the following processes: systematic review, meta-analysis, meta-synthesis, and mixed-method systematic review. These synthesis processes were introduced in Chapter 1, and the following section provides guidelines for critically appraising these synthesis processes to determine the status of knowledge for use in practice.

Critically Appraising Systematic Reviews

A systematic review is a structured, comprehensive synthesis of the research literature to determine the best research evidence available to address a healthcare question. A systematic review involves identifying, locating, appraising, and synthesizing quality research evidence for clinicians to use in practice (Bettany-Saltikov, 2010a; Craig & Smyth, 2012; Higgins & Green, 2008; Liberati et al., 2009; Rew, 2011). Systematic reviews are often conducted by two or more researchers and/or clinicians in a selected area of interest to determine the best research knowledge in that area (see Grove, Burns, & Gray [2013] for the process of conducting a systematic review).

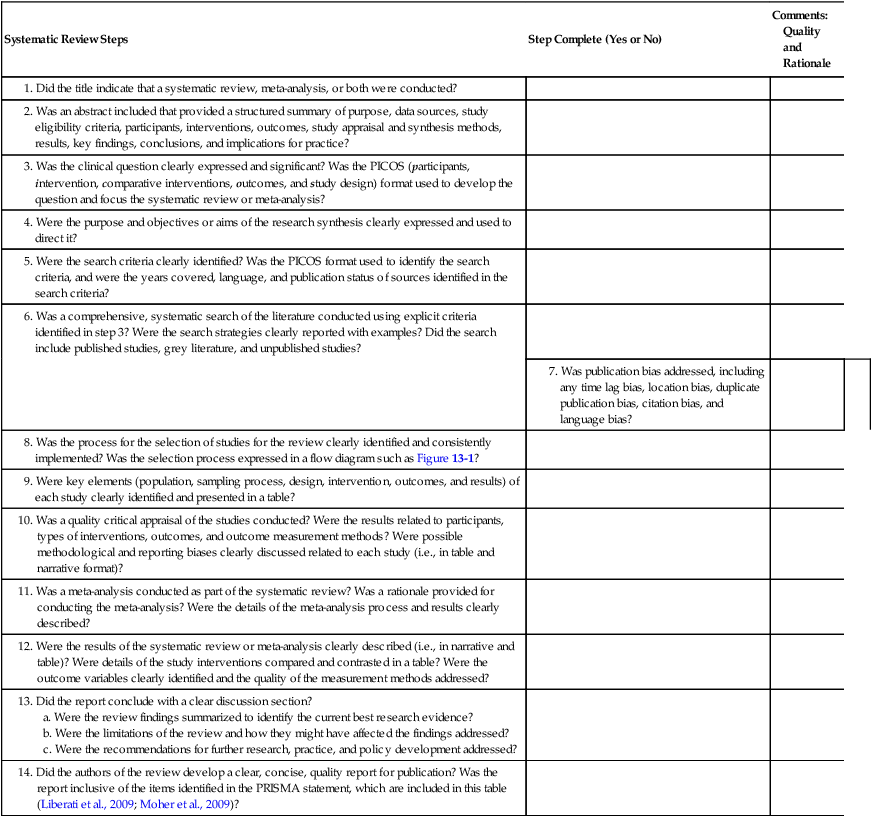

Systematic reviews need to be conducted with rigorous research methodology to promote the accuracy of the findings and minimize the reviewers’ bias. Table 13-2 provides a checklist for critically appraising the steps of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. These steps are based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Liberati et al., 2009) statement and other relevant sources to guide nurses in conducting systematic reviews (Bettany-Saltikov, 2010a, 2010b; Higgins & Green, 2008; Moore, 2012; Rew, 2011). The PRISMA statement was developed in 2009 by an international group of expert researchers and clinicians to improve the quality of reporting for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. It includes 27 items, which can be found at http://prisma-statement.org and are detailed in the article by Liberati and colleagues (2009). If the review process is clearly detailed in the report, others can replicate the process and verify the findings.

Table 13-2

Checklist for Critically Appraising Published Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

| Systematic Review Steps | Step Complete (Yes or No) | Comments: Quality and Rationale |

10. Was a quality critical appraisal of the studies conducted? Were the results related to participants, types of interventions, outcomes, and outcome measurement methods? Were possible methodological and reporting biases clearly discussed related to each study (i.e., in table and narrative format)? | ||

A systematic review conducted by Choi and Hector (2012) is presented here as an example, with the application of the critical appraisal steps outlined in Table 13-2. They conducted a systematic review that included a meta-analysis to determine the effectiveness of fall prevention programs in reducing the number and rate of falls in hospital and community agencies. You can find the publication by Choi and Hector (2012) in the CINAHL database of your closest library (see Table 13-1 for a description of CINAHL). We recommend that you read this article and use the guidelines in Table 13-2 to critically appraise this systematic review and compare your findings with the following discussion.

Step 1

Did the title indicate if a systematic review or meta-analysis was conducted?

Choi and Hector (2012, p. 188.e21) titled their research synthesis as “Effectiveness of Intervention Programs in Preventing Falls: A Systematic Review of Recent 10 Years and Meta-Analysis.” The authors clearly indicated the types of research syntheses (systematic review and meta-analysis) included in their publication.

Step 2

Did the abstract include a structured summary of the research synthesis?

Choi and Hector (2012) provided a clear, concise abstract that identified the purpose of the systematic review, data sources, study eligibility criteria, studies selected for review (17 RCTs), types of fall prevention programs, primary outcomes of number of falls and fall rates, critical appraisal of studies, results, conclusions, and implications for practice.

Step 3

Was a significant, clear clinical question developed to direct the research synthesis?

A systemic review or meta-analysis is best directed by a relevant clinical question that focuses the review process and promotes the development of a quality synthesis of research evidence. One of the most common formats used to develop a relevant clinical question to guide a systematic review is the PICO or PICOS format described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins & Green, 2008). The PICOS format includes the following elements:

P—Population or participants of interest (see Chapter 9 on sampling)

I—Intervention needed for practice (see Chapter 8 on nursing interventions)

C—Comparisons of the intervention with control, placebo, standard care, variations of the same intervention, or different therapies (see Chapter 8)

O—Outcomes needed for practice (see Chapter 10 on measurement methods and Chapter 14 on outcomes research)

S—Study design (see Chapter 8 on types of study designs)

Choi and Hector (2012) noted that falls were the leading cause of injury and deaths among older adults, with the direct medical costs estimated to be over $19.2 billion in 2000. Research syntheses had been conducted on fall prevention programs from the 1990s to 2000, but not for the last decade. What was not known was the effectiveness of the fall prevention interventions studied from 2000 to 2009. The population was older adults, and the intervention was fall prevention programs. The studies reviewed included different types of interventions, with most of the fall prevention programs including multiple approaches, such as individualized exercises for strength, coordination and balance, occupational therapy, home environmental and behavioral assessments, cognition assessment, medical examination, gait stability, and medication review. The intervention group was compared with groups receiving standard care, no treatment, or a variation of the treatment. The primary outcomes measured were number of falls and fall rate. The study design included synthesis of only RCTs using guidelines from the Cochrane Collaboration handbook (Higgins & Green, 2008; see Chapter 8 for a description of RCTs). The study design (RCTs) clearly focused the literature review but might have eliminated some important studies that could have expanded the knowledge related to the intervention, fall prevention programs.

Step 4

Were the purpose and objectives or aims of the review expressed?

Systematic reviews of research include a purpose and sometimes specific aims or objects to guide the synthesis process (Bettany-Saltikov, 2010a; Rew, 2011). The purpose identifies the major goal or focus of the review. Choi and Hector (2012, p. 188.e13) identified their purpose as follows: “To examine the reported effectiveness of fall-prevention programs for older adults by reviewing randomized controlled trials from 2000 to 2009.” This clearly focused purpose was used to direct their systematic review and meta-analysis, and no additional objectives were identified.

Step 5

Was the literature search criteria clearly identified?

Research reports of systematic reviews or meta-analyses need to identify the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to direct the literature search (see Table 13-2). The PICOS format might be used to develop the search criteria with more detail being developed for each of the elements. These search criteria might focus on the following: (1) type of research methods, such as quantitative, qualitative, or outcomes research; (2) population or type of study participants; (3) study designs, such as description, correlational, quasi-experimental, experimental, qualitative, or mixed methods; (4) sampling processes, such as probability or nonprobability sampling methods; (5) intervention and comparison interventions; and (6) specific outcomes to be measured. The search criteria also need to indicate the years for the review, language, and publication status (Bettany-Saltikov, 2010b; Higgins & Green, 2008; Rew, 2011).

Often searches have been limited to published sources in common databases, which excludes the grey literature from the research synthesis. Grey literature refers to studies that have limited distributions, such as theses and dissertations, unpublished research reports, articles in obscure journals, articles in some online journals, conference papers and abstracts, conference proceedings, research reports to funding agencies, and technical reports (Benzies, Premji, Hayden, & Serrett, 2006; Conn, Valentine, Cooper, & Rantz, 2003). Most grey literature is difficult to access through database searches and is often not peer-reviewed, with limited referencing information. These are some of the main reasons why grey literature is not included in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. However, excluding grey literature might result in misleading, biased results. Studies with significant findings are more likely to be published than studies with nonsignificant findings and are usually published in more high-impact, widely distributed journals that are indexed in computerized databases (Conn et al., 2003). Studies with significant findings are more likely to have duplicate publications, which should not be included in the systematic review or meta-analysis. More details on identifying publication bias are provided in the next section on critically appraising meta-analyses.

Choi and Hector (2012) designed their literature search strategies and their protocol for conducting their systematic review using sources such as the Cochrane Collaboration handbook (Higgins & Green, 2008) and the PRISMA statement (Liberati et al., 2009; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & PRISMA Group, 2009). PICOS format was also implemented with the literature search being directed by population of older adults, intervention of fall prevention programs, comparison of intervention groups with standard care and control groups, outcomes of number of falls and fall rates, and study designs limited to RCTs. The date restriction for the search was 2000 to 2009 based on the lack of research syntheses conducted in the last decade. The search was limited to published studies reported in English, which could result in important studies being omitted from the systematic review.

Step 6

Was a comprehensive, systematic search of the research literature conducted?

The key search terms, different databases searched, and search results need to be recorded in the systematic review and meta-analysis publications. Sometimes authors provide a table that identifies the search terms and criteria. The PRISMA statement recommends presenting the full electronic search strategy used for at least one major database, such as CINAHL or MEDLINE (Liberati et al., 2009). The search strategies used to identify grey literature and other unpublished studies need to be identified.

Choi and Hector (2012, p. 188.e14) described their search of the literature in the following:

Step 7

Was publication bias addressed?

Choi and Hector (2012) recognized the publication bias that occurs with using only published sources and not including grey literature. They also limited their search to the English language, resulting in a language bias. They noted that 33 studies were duplicated across the databases, and these were excluded, thus reducing the potential for duplication bias.

Step 8

Was the process for selecting the studies for review detailed?

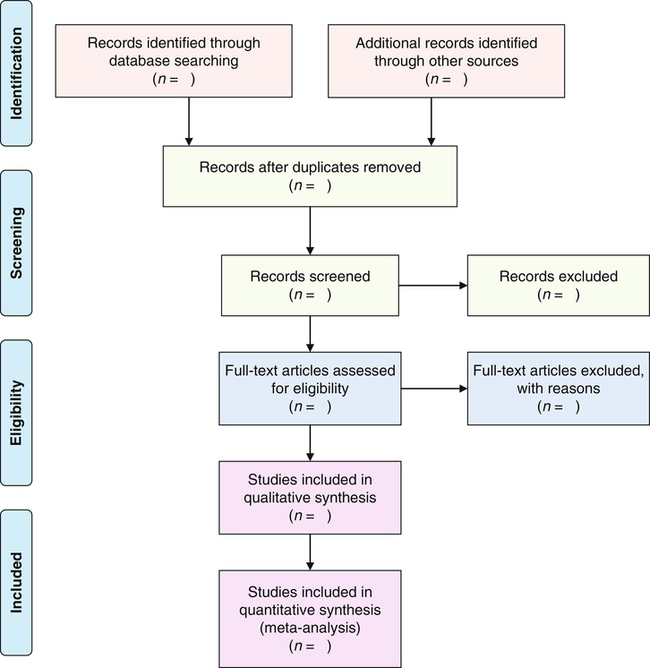

The selection of studies for inclusion in a systematic review or meta-analysis is a complex process that initially involves the review and removal of duplicate sources. The abstracts of the remaining studies are reviewed by two or more authors and sometimes by an external reviewer to ensure that they meet the criteria identified in step 5 (see Table 13-2). The abstracts might be excluded based on the study participants, interventions, outcomes, or design not meeting the search criteria (Bettany-Saltikov, 2010b; Higgins & Green, 2008; Liberati et al., 2009). After the abstracts meeting the designated criteria are identified, the next step is to retrieve the full-text citation for each study. If studies do not meet criteria, they need to be removed, with a rationale provided. The study selection process is best demonstrated by a flow diagram that was developed by the PRISMA Group (Liberati et al., 2009). Figure 13-1 shows this diagram, which has four phases: (1) identification of the sources; (2) screening of the sources based on set criteria; (3) determining if the sources meet eligibility requirements; and (4) identifying the studies included in the review.

Identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of research sources in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. (From Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Retrieved July 17, 2013, from http://www.prisma-statement.org.)

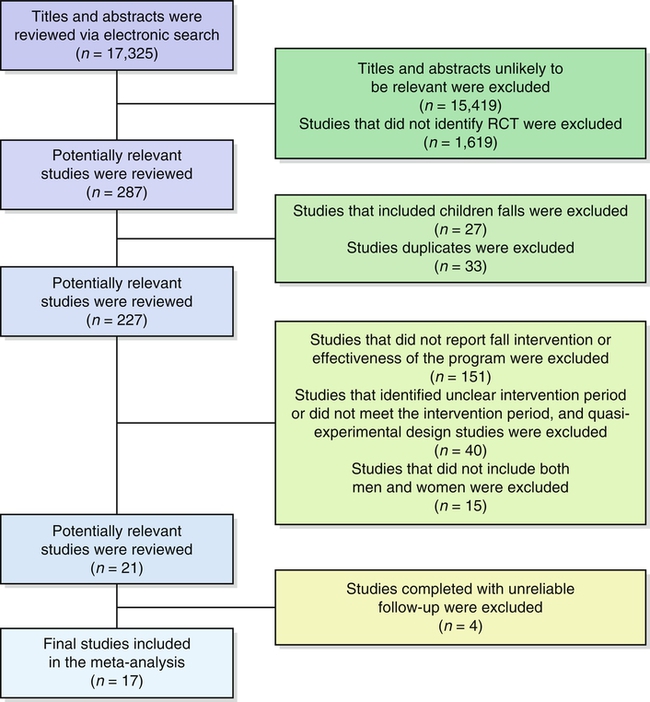

Choi and Hector (2012) provided a description of their selection of sources and a flow diagram that documented the final results of the 17 RCTs included in their systematic review, with a meta-analysis. The following excerpt identifies the steps that they took to select their studies for inclusion in their research synthesis:

“There were 33 studies duplicated across databases that were excluded.… Studies with titles and abstracts unlikely to be relevant were excluded (n = 15,419) followed by exclusion of studies that did not identify an RCT (n = 1619). A total of 287 potentially relevant studies were reviewed by the primary author (M. C.). We excluded studies of fall-prevention programs for children (n = 27). The primary search (completed from July 2009 to March 2010) generated a total of 227 studies.… Of the 227 publications that met the criteria for meta-analysis, 17 studies remained [Figure 13-2].”

Choi and Hector, 2012, p. 188.e14

Step 9

Were key elements of the studies presented?

Critical appraisals of studies for systematic reviews and meta-analyses are best done by constructing a table describing the characteristics of the included studies, such as the purposes of the studies, populations, sampling processes, interventions, outcomes, and results (Bettany-Saltikov, 2010b; Higgins & Green, 2008; Liberati et al., 2009). Choi and Hector (2012) detailed the key elements of the 17 studies in a table. The table included authors of the study, year, sample size of control and intervention groups, intervention and follow-up period, intervention model, setting, mean age of subjects, and brief description of the intervention programs. The table would have been stronger if the sampling methods, outcomes measured, and key results for the 17 studies had been included in a table format.

Step 10

Were the studies critically appraised?

Two or more experts need to review the studies independently and make judgments about their quality. The critical appraisal of the studies is often difficult because of the differences in types of participants, designs, sampling methods, intervention protocols, outcome variables and measurement methods, and presentation of results. The studies are often rank-ordered based on their quality and contribution to the development of the review (Bettany-Saltikov 2010b; Liberati et al., 2009). Choi and Hector’s (2012) critical appraisal of the 17 studies involved examining the sample characteristics in the studies, types of interventions, settings of interventions, and intensity of the intervention. The final results of the studies were pooled using a meta-analysis.

Step 11

Was a meta-analysis conducted as part of the systematic review?

Some authors conduct a meta-analysis in the synthesis of sources for their systematic review (Liberati et al., 2009). Because a meta-analysis involves the use of statistics to summarize results of different studies, it usually provides strong, objective information about the effectiveness of an intervention or solid knowledge about a clinical problem. The authors of the review need to provide a rationale for conducting the meta-analysis and detail the process that they used to conduct this analysis. For example, a meta-analysis might be conducted on a small group of similar studies to determine the effect of an intervention. The systematic review conducted by Choi and Hector (2012) included a meta-analysis of the 17 studies and provided a detailed discussion of the rationale for the meta-analysis and results for this procedure. The next section provides more details on conducting a meta-analysis.

Step 12

Were the results of the review clearly presented?

The results of a systematic review and meta-analysis should include a description of the study participants, types of interventions implemented in the studies, outcomes measured, and measurement methods. The results of the different types of intervention might be best summarized in a table that includes the following: (1) study source; (2) structure of the intervention (stand-alone or multifaceted); (3) specific type of intervention (e.g., physiological treatment, education, counseling, or behavioral therapy); (4) delivery method (e.g., demonstration and return demonstration, verbal, video, or self-administered); (5) length of time the intervention is implemented; and (6) statistical difference between the intervention and control, standard care, placebo, or alternative intervention groups (Liberati et al., 2009).

Choi and Hector (2012) included a description of the 17 fall prevention interventions in a table indicating that most of the interventions were multifactorial rather than an individual action. The interventions and their follow-up period had to be at least 5 months. The authors indicated that the primary outcomes of number of falls and fall rates were measured in different ways in the studies, which limited the quality of the results and findings of the systematic review and meta-analysis. The following excerpt presents the key results from the systematic review and meta-analysis:

Step 13

Did the report conclude with a clear discussion section?

In a systematic review or meta-analysis, the discussion of the findings includes an overall evaluation of the types of interventions implemented and the outcomes measured. You can also expect the methodological issues or limitations of the review to be addressed. A quality discussion section explicitly connects the findings to the study’s framework to identify the theoretical implications of the findings. Finally, the discussion section needs to provide recommendations for further research, practice, and policy development (Bettany-Saltikov, 2010b; Higgins & Green, 2008; Liberati et al., 2009).

Choi and Hector (2012) provided a discussion of their findings, limitations, and recommendations for research and practice. The report would have been strengthened by including a framework and linking the findings back to the framework to indicate current knowledge regarding the effect of fall prevention programs on number of falls and fall rates. The following excerpt summarizes the key aspects of the discussion section of their report:

Implications for practice

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide important, evidence-based knowledge for use in practice. Choi and Hector’s (2012) recommendations provide clear evidence-based interventions that students and RNs might use to reduce the falls in their agencies and institutions. The QSEN (2013) implication is that critically appraising systematic reviews and using relevant evidence in practice is essential for achieving EBP.

Step 14

Was a clear concise report developed for publication?

The systematic review or meta-analysis report needs to include the content discussed in the previous 13 steps. You can use Table 13-2 when critically appraising a systematic review, indicate if the step is present, and comment about its quality with, supporting rationale. In summary, Choi and Hector (2012) developed a strong systematic review and meta-analysis for publication. The title clearly indicates the types of syntheses conducted. The clinical question addressed followed the PICOS format, and the purpose of the synthesis is clearly focused. The search of the literature might have been more rigorous and included additional studies, especially grey literature. The selection of studies for the synthesis was clearly presented in a flow chart and documented with rationale. The studies selected for the systematic review and meta-analysis were critically appraised, and the results from these syntheses were clearly presented in tables and narrative. The publication concluded with relevant findings, limitations, and recommendations for research and practice.

Critically Appraising Meta-Analyses

A meta-analysis is conducted to pool or combine statistically the results from previous studies into a single quantitative analysis that provides one of the highest levels of evidence about the effectiveness of an intervention (Andrel, Keith, & Leiby, 2009; Craig & Smyth, 2012; Higgins & Green, 2008; Liberati et al., 2009). This approach has objectivity because it includes analysis techniques to determine the effect of an intervention while examining the influences of variations in the studies included in the meta-analysis. The studies included in a meta-analysis need to be examined for variations or heterogeneity in areas such as sample characteristics, sample size, design, types of interventions, and outcome variables and measurement methods (Higgins & Green, 2008). Heterogeneity in the studies included in a meta-analysis can lead to different types of biases (see later). Meta-analyses that include more homogeneous (similar) studies have less bias and usually provide more valid findings (Moore, 2012).

Statistically combining data from several studies results in a large sample size, with increased power to determine the true effect of a specific intervention on a particular outcome (see Chapter 9 for a discussion of power). The ultimate goal of a meta-analysis is to determine if an intervention (1) significantly improves outcomes, (2) has minimal or no effect on outcomes, or (3) increases the risk of adverse events. Meta-analysis is also an effective way to resolve conflicting study findings and controversies that have arisen related to a selected intervention (Higgins & Green, 2008).

Strong evidence for using an intervention in practice can be generated from a meta-analysis of multiple, quality studies such as RCTs and quasi-experimental studies. However, the conduct of a meta-analysis depends on the accuracy, clarity, and completeness of information presented in studies. Box 13-1 provides a list of information that needs to be included in a research report to facilitate the conduct of a meta-analysis. You might use the information in Box 13-1 as a checklist to determine if the reports of RCTs and quasi-experimental studies are complete.