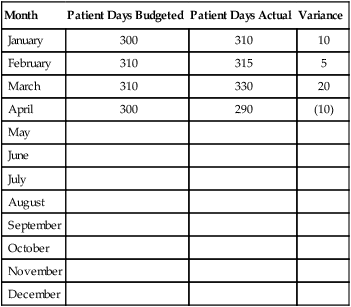

National Health Expenditures (NHEs) are a measure of spending for health care in the United States. In 1998, NHE exceeded $1 trillion for the first time. By 2020, NHE are projected to increase to $4.6 trillion (Keehan et al., 2011). Considered from another perspective, this amount of money in 1998 represented 13.1% of the gross domestic product (GDP), the value of all the goods and services produced in the United States in 1 year. By 2020, NHE is projected to represent 19.8% of the GDP. By 2014, when major coverage expansions from the Affordable Care Act begin, national spending growth is expected to reach 8.4%. All nurses will be involved in budgeting for nursing services in different ways and to different degrees. Staff nurses in particular often report, “I just want to take care of patients—don’t bother me with money matters.” Some nurse administrators have said, “Show me your budget and I will tell you your values.” Nurses at all levels need to understand that “finance is not a dirty word” (Sorbello, 2008). Given that health care resources are limited, nurses do compete for these resources and need to understand financial management. In many organizations, staff nurses are expected to be aware of their unit’s financial performance and the impact their decisions may have on it. Staff nurses’ involvement is essential to the ability to contain costs at the unit level because they make many decisions about supply and resource use. There are three main types of organizational budgets, as follows: 1. Capital budget: This budget is the plan for the purchase of major equipment or assets. 2. Operating budget: The operating budget is the annual plan for the unit’s or organization’s daily functioning revenue and expenses for a single year. For nursing units, this is a plan that lays out what it is going to cost to run the unit in the coming year. It includes such things as supplies, telephones, mailing, paper, and copy machines. In addition, there may be a cost allocation for such things as heat, light, and housecleaning. 3. Personnel budget: This is the staffing budget of the cost center (department or unit). It may be developed as part of the operating budget or it may stand alone. 1. Preparation: As a beginning point, the manager reviews the organization’s strategic plan and the last year’s budget for the cost center. The strategic plan will aid in writing a budget justification for any capital requests as well as linking to organizational priorities. The prior year’s budget for the cost center will help the manager to identify volume projections and changes in the past year and potential changes in the coming year. In the hospital, patient days are the usual volume measurement. If the manager of a surgical unit knows that two general surgeons are being recruited to the organization, it is reasonable to project an increase in patient days. By reviewing the previous year’s data, an informed projection can be made about the increase that can be anticipated. Similarly, the manager may be aware of factors that will decrease the volume of patient days, such as a new hospital being built in the suburbs. In ambulatory care, the volume unit of measurement is clinic visits. If a new nurse practitioner is being hired, how would that impact the volume of visits projected? 2. Completing the forms: The manager will be given budget documents to use in preparing the cost center budget. These are usually spreadsheets sent electronically. They include embedded formulas that compute the summary statistics, thereby reducing human error. Firm due dates are assigned for the completion of this first draft of the budget. The finance department then “rolls up” the unit budget into the organizational budget. 3. Revise and resubmit: As budget documents go through review by senior management, requests tend to exceed the available resources. This necessitates review, adjustment, and appeal. This is when the competition for available resources enters the process. Managers may be asked to reduce their unit budget by a dollar percentage, leaving the question “where to cut” as the manager’s decision. At other times, a manager may be directed to reduce the personnel budget by a number of full time equivalents (FTEs). This is the point at which the nurse manager must skillfully advocate for patient care, ensuring safety and quality. The nurse manager’s knowledge of clinical care processes may be in conflict with directives of a financial administrator who lacks clinical expertise. This is the time when nurses must be prepared to “speak finance” in order to effectively respond to budget challenges. There may be multiple iterations of rebudgeting before the final budget is approved. Table 22-1 shows a sample volume budget flow sheet. Historical trend data are needed (e.g., occupancy percentages by time frames such as weekly or monthly) to determine growth projections and any impact of seasonality. The volume of services delivered for a year may be expressed as patient days, visits, procedures, or other units of service. Effects on volume are environmental effects such as reimbursement changes, new programs, process improvements, new technology, and marketing. If volume projections depend on another service or department, it is important for the two departments to communicate closely so that similar assumptions are used in establishing volume projections. TABLE 22-1 Once the volume projection has been completed, the manager can determine the personnel services (or staffing budget) portion of the expense budget. Calculation of staffing is complex and, given that staffing expenses generally are the largest portion of the nursing operating budget, nurse managers and nurse executives must have a consistent and well-defined approach to estimating staffing expenses. The methodology used will likely vary from organization to organization. Dunham-Taylor and Pinczuk (2006) described the following method that may be used to estimate staffing expenses. Table 22-2 displays a sample budget expense sheet for salaries, and Table 22-3 demonstrates how personnel budgets might be displayed. Salary increases might also be included as another column. TABLE 22-2 Budgeted Salary Expense Flow Sheet TABLE 22-3

Budgeting, Productivity, and Costing Out Nursing

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Huber/leadership/

BACKGROUND

DEFINITIONS

THE BUDGET PROCESS

Operating Budget Development

Month

Patient Days Budgeted

Patient Days Actual

Variance

January

300

310

10

February

310

315

5

March

310

330

20

April

300

290

(10)

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

Expense Item

Budgeted

Actual

Salaries

Regular

Overtime

On-call

Vacation

Holiday

Illness

Other

Total Salaries

Position

Name

Fte

Hourly Wage ($)

Yearly Salary ($)

RN

Smith

1.0

23.08

48,006

RN

Jones

1.0

26.92

56,000

LPN

Roe

0.5

13.94

14,498

CNA

Ash

1.0

10.57

21,986

Unit clerk

Oak

1.0

14.00

29,120 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Budgeting, Productivity, and Costing Out Nursing

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access