Introduction

Breech presentation is where the lie of the baby is longitudinal and the baby’s buttocks are in the lower segment of the mother’s uterus.

Following the term breech trial (TBT) (Hannah et al., 2000), midwives today may have limited experience of seeing or being involved in caring for a woman having a vaginal breech birth. They may approach a vaginal breech birth with the same lack of confidence and fear observed in inexperienced obstetricians. However, midwives need to remember that in carefully selected/assessed women, vaginal breech birth can be a safe and fulfilling birth option (Alarab et al., 2004; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), 2006b).

Incidence

- 25% of babies adopt a breech position at some time in pregnancy, and 3–4% remain breech at term (RCOG, 2006b).

- The TBT (Hannah et al., 2000) has increased breech caesarean section (CS) rates. The UK CS rate for breech presentation rose from 69% in 1993 to 88% in 2001 (RCOG, 2001), and is rising still. Breech now accounts for 11% of all caesareans (RCOG, 2007).

- Other countries have had similar increases: the Netherlands CS rate for breech has risen from 57 to 81% (Schutte et al., 2007), whilst in France it rose from 43% in 1998 to 75% in 2003 (Carayol et al., 2007).

Facts

- Many babies appear to adopt a breech presentation for no particular reason. However, a minority will adopt a breech position because of ‘problems’ such as short or entangled cord, prematurity, placenta praevia or fetal abnormalities.

- Irrespective of mode of delivery, breech presentation is associated with increased subsequent disability; in a few cases failure to adopt a cephalic presentation may be a marker for fetal impairment (RCOG, 2006b).

- For a woman with predisposing factors, such as diabetes, fetopelvic disproportion, a previous macrosomic baby, or a suspected large baby and poor labour progress, a CS is usually advisable (RCOG, 2006b).

- Evidence suggests that external cephalic version (ECV) should be offered to all women with an uncomplicated breech baby at term (37–42 weeks) (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2003; RCOG, 2006a).

- Following TBT the RCOG (2006b) advises, ‘Women should be advised that planned (breech) CS carries a reduced perinatal mortality and early neonatal morbidity… compared with planned vaginal birth’, but the TBT trial has been criticised for clinical and methodological flaws. Later follow-up of TBT babies shows fewer perinatal deaths with planned CS were balanced by more babies with neurodevelopmental delay (Whyte et al., 2003).

- Women should be facilitated to make an informed choice about their birth options and should not be coerced into one particular mode of delivery. These discussions should include the possible differences between a ‘managed’ vaginal breech birth and one ‘facilitated’ by a skilled practitioner.

- Midwives working in all environments should be prepared for the possibility of being the only professional around when faced with an unexpected or undiagnosed breech baby. It is, therefore, important that they are prepared to deal with this eventuality and that they have the training, knowledge and skills to assist the woman and her baby at this time (CESDI, 2000; Robinson, 2000).

- Whilst having a good heart rate, breech babies may be slower to breathe spontaneously than cephalic babies, and may require bag-and-mask resuscitation to establish breathing.

Types of breech presentation

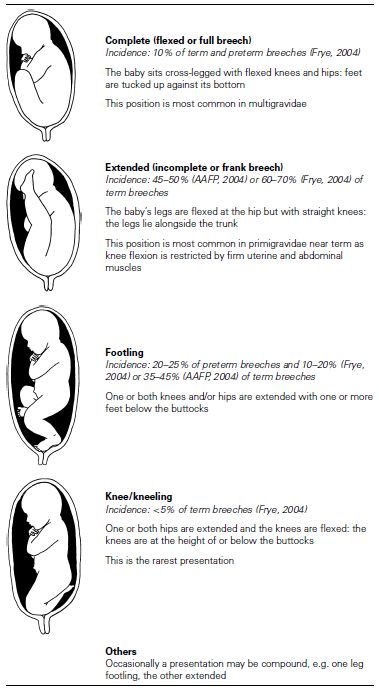

The baby in a breech presentation will adopt a variety of positions, similar to a cephalic baby, with the sacrum being the denominator. Table 13.1 describes different breech presentations.

Women’s options and the provision of care

The midwife needs to explore his/her own feelings and prejudices and remain unbiased and non-judgemental, acting in a manner that will facilitate both informed choice and decision making as well as enabling the woman to access appropriate care.

- Explore the options – ECV, vaginal breech birth, and CS; home or hospital.

- Women can choose who assists at the birth: an NHS midwife, an independent midwife or an obstetrician.

- Discuss the possible difference between a vaginal breech birth that is ‘managed’ and one that is ‘facilitated’ by a skilled practitioner/midwife. Managed/medicalised breech birth tends to include a package of epidural anaesthesia, routine episiotomy and lithotomy position for the delivery. A facilitated birth encourages the breech baby to birth through supporting the woman in upright postures and only intervening should a direct indication arise.

- Choice may be restricted due to ‘local policy’ or a lack of suitably skilled practitioners.

- Where a hospital is unable to safely offer the woman the option of a vaginal breech birth, she should be referred to another hospital where this choice is available (RCOG, 2006b).

Table 13.1 Types of breech presentation.

Self-help measures

A woman may wish to try self-help measures to turn a breech antenatally, thus promoting a feeling of active involvement and enabling her to retain a feeling of active participation in her situation. Methods include postural management, e.g. knee-chest position and pelvic rocking, visualisation, swimming, massage, talking to her baby as well as complementary therapies such as hypnotherapy, homeopathy, acupuncture, acupressure, moxibustion, chiropractic or osteopathic intervention. There is little hard evidence for any of these methods. Only acupuncture and moxibustion have undergone randomised controlled trials (Neri et al., 2004; Coyle et al., 2005). Whilst these results look promising, the evidence base is still incomplete for these and all self-help/complementary measures.

External cephalic version

All women should be offered information about the safety and benefits of ECV at term. When it is undertaken by a trained operator, the success rate will be around 50%; however, this rate may vary from 30 to 80% and depend on a number of factors including engagement of the breech, liquor volume, uterine tone, race and parity (RCOG, 2006a).

- The success rate of ECV may be increased by the use of tocolysis (RCOG, 2006a).

- Following successful ECV, spontaneous reversion to breech presentation is said to be less than 5% (Impey & Lissoni, 1999).

- Hofmeyr (2000) suggests that even when a breech presentation is encountered in labour and the membranes remain intact, the limited data available indicates that ECV performed with tocolysis has a reasonable success rate.

- Rhesus negative women who have ECV performed should be offered anti-D prophylaxis (NICE, 2002).

Caesarean section

Many obstetricians now recommend CS for breech presentation regardless of individual circumstances. This is primarily due to the TBT (Hannah et al., 2000), which reported an increased 1% mortality risk and 2.4% early neonatal morbidity risk in breech vaginal delivery over CS. Hannah et al. concluded: ‘planned caesarean section is better than planned vaginal birth for the term fetus in the breech presentation’. Whilst this recommendation has been largely accepted and implemented by obstetricians, others have challenged it (Robinson, 2000/2001; Banks, 2001; Gyte, 2001; Lancet Correspondence, 2001). One criticism is that the ‘vaginal’ breech deliveries in the TBT were dorsal ‘managed’ breech extractions, and women were not allowed to labour in upright positions. Some women also moved from their randomised groups, potentially confounding the result. Glezerman (2006) concludes that in the light of serious methodological and clinical flaws ‘the original term breech trial recommendations should be withdrawn’. Alarab et al. (2004) state that with strict selection criteria, adherence to a careful intrapartum protocol and an experienced obstetrician in attendance a vaginal breech delivery at term can be achieved safely.

In a 2-year follow-up study to the TBT (Whyte et al., 2003), an unexpectedly high number of babies born by breech CS showed later neurodevelopmental delay, which balanced the smaller numbers of perinatal deaths in that group. Another observational prospective study with an intent-to-treat analysis demonstrated a lower mortality and morbidity than the TBT (Goffinet et al., 2006).

The practice of CS for breech babies in the belief that it is safer may become a self-fulfilling prophecy as attendants become less skilled in vaginal breech birth. With a rising breech CS rate too, few clinicians have vaginal breech experience (RCOG, 1999, 2006b). It is to be hoped that in the next few years, the debate following the TBT will lead to a better understanding of breech issues, and that women will not be pressured into CS without proper consideration of the relative risks.

Extracts from RCOG (2006b) Guidelines for the Management of Breech Presentation state that:

- Women should be fully informed on all aspects relating to breech birth both for current and future pregnancies and have careful assessment before selection for vaginal breech birth.

- Induction of labour may be considered if individual circumstances are favourable.

- Augmentation in labour is not advisable. Slow progress at any stage should be considered as possible fetopelvic disproportion, and a CS may then be indicated.

- Routine CS for a preterm breech baby should not be advised.

- Diagnosis of breech presentation during labour should not be a contraindication for vaginal breech birth.

- In a twin pregnancy where the first baby is breech, it is suggested that the data relating to a singleton breech can be used to aid decision making. Where the second twin is breech, the RCOG (2006b) states that routine CS should not be performed. (For more information on twins see Chapter 14.)

Midwives are strongly advised to read and evaluate all the literature for themselves. It may also fall to them to inform colleagues, managers and obstetricians of current national guidelines.

Concerns and possible complications with a breech birth

Hypoxia

Hypoxia has been identified as the commonest cause of death in breech babies. CESDI (2000) suggests that lack of recognition and inaction are major factors.

Umbilical cord prolapse

Incidence: 3.7% in breech (Confino et al., 1985).

Umbilical cord prolapse is

- More frequent in primigravidae than multigravidae (6% and 3%, respectively).

- More common in premature labour and incomplete presentations (e.g. footling).

- More common where artificial rupture of membranes (ARM) is performed, which increases the incidence of cord compression.

Prolapse does not always cause cord compression. Where the cervix is fully dilated, a vaginal birth may still be possible (see Chapter 16).

Entrapment of aftercoming head

Incidence: 0–8.5% at term (Cheng & Hannah, 1993).

It is thought that if the diameters of a baby’s bottom are smaller than those of its head it is more likely to pass through a cervix that is not fully dilated. This may result in the entrapment of the aftercoming head behind a partially open cervix.

However, the specific presentation of the breech baby appears significant. It is now suggested that the diameters of the term breech baby’s bottom will be the same size as the head (Stevenson, 1993), with the bitrochanteric diameter measuring around 9 cm, similar to the average biparietal diameter of 9.5 cm (Frye, 2004).

- ‘If the frank or complete breech passes easily through the pelvis, the head can be expected to follow without difficulty’ (Hofmeyr, 2000).

- In a term baby, if the head is not going to pass through the cervix and pelvis, the buttocks would also be obstructed and labour will not progress (Hofmeyr, 2001 citing Gebbie, 1982).

- Entrapment is more common in a preterm baby (Stevenson, 1993) and may be related to maternal pushing being encouraged prior to, or following, misdiagnosis of full dilatation.

Hyperextension of the baby’s head (star gazing)

Incidence: 5% (Confino et al., 1985).

If hyperextension of the head is detected by ultrasound scan (USS) at term, a CS will be advised.

Hyperextension may occur due to:

- Cord around baby’s neck

- Placental location

- Muscle spasm in baby

- Abnormalities in either the uterus or the baby

- May be caused in labour by unnecessary intervention of the carer. Spontaneous pushing, not traction, should be encouraged; traction may cause extension of the baby’s arms and head (Hofmeyr, 2000).

Head and neck trauma

Forceful traction by the carer may cause iatrogenic brain and spinal injuries (Banks, 1998).

Premature placental separation

This may be linked to maternal position in the second stage of labour, especially where the woman adopts a fully upright position. This is due to the centre of gravity being higher in a breech than in a cephalic birth, resulting in more traction being placed on the cord and placenta by gravity (Cronk, 1998).

Labour and birth

Preparation/birth planning

Frank and open discussion between the midwife, the woman and her partner, where all options available are explored, will help the woman reach a decision about whether or not to have a vaginal breech birth. It may also clarify issues for the woman and enable her to develop an appropriate and individual birth plan.

Points to consider include the following:

- The baby is in a good position and not considered too large.

- A skilled and competent midwife will support the woman in a breech birth.

- The woman, her partner and the midwife are informed regarding the anticipated process and progress of a breech labour and birth.

- The woman has confidence in her body and her midwife.

- Good communication between the woman and the midwife at all times.

The midwife’s role

- To support the woman in her innate ability to birth her baby.

- To have confidence in the woman’s ability to birth her baby.

- Not to ‘manage’ the woman’s care or labour process, encourage and enable the woman to respond intuitively and to express her own needs and wishes.

- To ensure and maintain a sound knowledge of skills and techniques to assist a breech birth, should it become necessary.

- To recognise, assess and respond to problems, should they occur.

- To act as advocate for the woman at all times.

It is important that midwives ensure they have appropriate support for themselves. Having a colleague present who is experienced in non-medicalised breech birth will provide support for the midwife.

Mechanisms of a breech birth

Midwives should refer to a suitable textbook to familiarise themselves with the various mechanisms. A very detailed and comprehensive description, supported by diagrams, can be found in the book by Anne Frye (2004).

Onset of labour

Midwifery care and support is the same as for any labour.

- With maternal consent, palpate the abdomen to check that the presentation and position of the baby has not changed.

- Banks (1998) suggests that a vaginal assessment in early breech labour is important to determine the presenting part and to exclude cord, foot, knee or compound presentation. This should be carried out with the woman’s consent and awareness of the purpose of the examination. She should be advised that it is expected that cervical dilatation may be minimal at this stage to avoid her feeling demotivated.

- Cooper (1992) suggests that the presenting part is often higher in the pelvis than the midwife would expect with a cephalic presentation, and that the station is likely to go up and down more during labour.

- If the woman is examined in a semi-recumbent position, assist her into an upright position immediately afterwards to avoid problems such as postural hypotension, fetal heart rate (FHR) irregularities and slowing of labour progress (Sleep et al., 2000; Gupta et al., 2004).

Pain management

Encourage the woman to apply skills she may have learnt antenatally such as relaxation, visualisation, vocalisation and mobility. Use massage, TENS, support and so on.

The use of a birthing pool is controversial and needs to be explored on an individual basis according to the wishes of the woman, the experience of the individual midwife and the place of the birth. The benefits of water are well documented (see Chapter 3), and those benefits, it could be argued, would be of use to a woman having a spontaneous vaginal breech birth, especially in the first stage of labour. This may prove challenging for both the woman and her carer where local guidelines on the use of a birthing pool exclude any presentation other than cephalic.

Midwives interested in exploring the use of water in breech presentation (and other unusual situations) may find work by Dr Herman Ponette in Belgium and Cornelia Enning in Germany helpful (see ‘Useful contacts’).

There is no evidence that the routine use of an epidural is appropriate in a vaginal breech birth; women should have a choice of analgesia (RCOG, 2006b). However, obstetricians may recommend it believing that it may prevent the premature urge to push and also enable them to carry out obstetric manoeuvres. This may be acceptable to the woman and be part of her decision-making process. Women need to be fully informed of the risks and benefits of an epidural including the restrictions it may place on them in terms of mobility and the inability to adopt upright positions to facilitate a breech birth.

First stage

- Care and observations are the same as for a cephalic birth:

Avoid unnecessary vaginal examinations (VEs)

Avoid unnecessary vaginal examinations (VEs)Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree