Chapter 10 Breastfeeding and public health

Introduction

Historically, there was only one way to nourish infants: by putting them to the breast, be it the natural mother or a wet nurse. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, most babies received human milk. Although we know from early literature that babies were often fed additional weaning foods that may not be approved of today, nonetheless pre-19th-century infants could expect to benefit from milk that was designed for them. This provided protection against diseases and the emotional closeness that is provided through breastfeeding that, in the 20th century, became known as bonding or attachment. After the Industrial Revolution, social and economic change directly impacted on family life and influenced infant feeding practices significantly, so that by the post-war years of the 1960s and 1970s, breastfeeding rates among UK mothers fell significantly. Today, breastfeeding rates in the UK have improved markedly, but vary enormously across social and geographical areas. This fall and gradual rise of breastfeeding has, it is argued, been a significant factor in both infant and maternal health and, therefore, played an important role in the public health debate.

Historical background

Prior to the 19th century, breastfeeding or wet nursing were the most accessible and natural ways to feed a baby. Whilst it is known that substitutes were used and provided, via a sheep’s horn for example (such as goats milk and flour with water), the majority of infants would have received human milk. Breastfeeding became a public health issue during the 19th century. As the Industrial Revolution began to have a major effect on the economy in Western Europe, infant mortality was at an all time high. As agriculture declined, urban living became a necessity for many in the search for work, and poor housing, overcrowding, squalor and the attendant scourges of infestation and infection, such as cholera, typhoid and syphilis, took their toll on as many as 250 infants per 1000. As Gabrielle Palmer (1993) reliably informs us in her book The politics of breastfeeding, the movement of industry away from cottages and family-based units in the rural areas and into the urban settings had a serious economic and social outcome for women and their children. Whereas child rearing and infant feeding had been a natural part of the daily life of the cottage industrialist, the move to a capitalist economy, where the means of production was centrally based in a factory, meant that women who had to work to live did not have the flexibility during the working day to breastfeed their infants. Protection from infection, as well as the provision of essential nutrients and the ability to manage their own fertility were thus limited for women working in industrialised societies. Breastfeeding as the natural method of feeding, therefore, became increasingly redundant as entrepreneurs, such as Henri Nestle, realised the niche market for artificial feeding and started to produce dried milk powder to replace breastfeeding. Prior to this time, the only alternative to breastfeeding had been wet-nursing – the practice of hiring another breastfeeding woman to feed the infant. This in itself had been a source of respectable income for many women who gained both stability and status by breastfeeding the babies of noble women. The vast majority of women, however, fed their own babies and not only was infant mortality lower in most areas before the Industrial Revolution (about 150 per 1000), women were able to take advantage of the contraceptive effects of lactation to space their families. Indeed, Palmer (1993) remarks on the fact that noblewomen often had much larger families, miscarriages and stillbirths than working women, as they did not tend to breastfeed their own babies. The daughters of the cottage industrialists would have been brought up not only as skilled helpers in the cottage industry, but as able mothers who would have no difficulty in breastfeeding her own children alongside the hard and often long working day.

Combining work outside the home with child rearing, within an economy that was driven by capitalism and controlled by patriarchy, deprived women of the power they had had to determine the health and future of their offspring. The only way to maintain some independent means of sustaining themselves and their children was to work in the factories and mills. Whilst breastfeeding continued in rural areas to be successfully sustained, it declined in the urban populations as artificial milks and their contaminants flooded the market, this was seen by many women as the only viable alternative. Public health officials such as Dr Reid (cited by Palmer, 1993), who exhorted women to return to the natural feeding of their infants, overlooked the fact that most women were powerless to do so and, thus, the moral debate over breastfeeding versus artificial feeding was inaugurated. Women who breastfed were seen as harlots, fallen women who wet-nursed to make a living or impoverished women of little moral worth. Working women, for whom breastfeeding was increasingly impossible, were selfish beings who worked to make their own lives better and had little care for their children. Women in the 19th century were in a Catch-22 situation and the legacy of this continues for women today, where arrangements to breastfeed or express milk in the workplace remain unusual and breastfeeding in public can still cause a moral outcry. Indeed, the influence of Westernised economic thought can now be seen to be infiltrating traditional agricultural economies in the developing world. Maher (1992) describes how in one North African tribe women have been almost forced into artificial feeding by the change from a self-sufficient agriculture to a cash-crop economy. The men command the power in the community through the sale of cash-crops in the urban markets, and they retain the profits. The women can only maintain a degree of power by using some of the wealth to purchase formula milk for their infants, a practice that is undoubtedly reinforced by Westernised marketing methods. To breastfeed means to surrender access to the means (and ends) of production, which the women themselves have played a major part in producing.

The Innocenti Declaration

The importance of this international declaration cannot be over-emphasised in terms of how pubic health policy and practice within the states that signed the declaration have been, or could have been, developed. It has been the guiding principle of the work of UNICEF in working across countries to develop the Baby Friendly Initiative and thus to enable organisations and practitioners to promote and sustain good breastfeeding practice and policy. This is enshrined in the Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (UNICEF 1996).

The purpose of introducing such declarations and plans internationally is to promote and support breastfeeding to enable both mothers and babies to realise the full health benefits of breast milk, both physical and psychological. As suggested in the introduction, breastfeeding rates have declined since the industrial revolution, and particularly since the Second World War and the economic boom of the 1960s. Against this, the evidence for the public health benefits of breastfeeding has become increasingly more convincing and sophisticated. It has also become possible through better data-collection systems to identify more precisely what the prevalence of breastfeeding is across the UK and where there might be a need for more targeted support.

Incidence and prevalence of breastfeeding in the UK

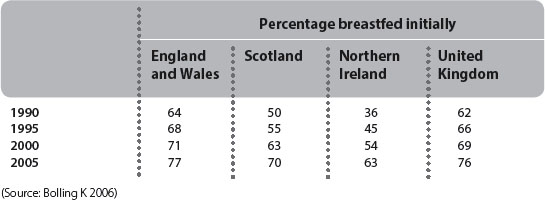

The most recent survey was conducted in 2005 and early results were published in 2006, with reference to the previous 2000 survey. The Health and Social Care Information Centre (IC) randomly selected a sample of over 19 848 women from registrations of births compiled by the General Register Offices of England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Of these, a total of 62% responded to an initial questionnaire when their babies were between 6 and 10 weeks old. These were followed up by further questionnaires when the babies were 4-5 months and 8-9 months old. The IC defines the incidence of breastfeeding as the proportion of babies who were breastfed initially, even if they were put to the breast only once. Prevalence of breastfeeding is defined as the proportion of babies who were wholly or partially breastfed at specific ages. These definitions have been used since the 1975 survey and are, therefore, helpful for comparative purposes. However, they do disguise the fact that some babies may only be breastfed for a very short time and, in relation to incidence in particular, these babies are counted in the same way as babies who were exclusively breastfed from the moment of birth. The health benefits of exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months as recommended by WHO (2002) are, therefore, difficult to extract from the ONS/IC data. However, as Table 10.1 shows, there has been an overall increase in the incidence of breastfeeding since 1995. The obvious issue that these data draw our attention to is one of difference in the incidence of breastfeeding between the UK constituent countries, breastfeeding being highest in England and lowest in Northern Ireland; however, breastfeeding rates in Northern Ireland between 2000 and 2005 rose more significantly than any other country (9% vs 6 and 7% in Scotland and England and Wales). There are regional variations within these figures; for example, the incidence of breastfeeding in London and the South East in 2000 was 81%, compared with 61% in the North of England (Hamlyn et al 2002). There have been significant overall increases in breastfeeding initiation since 1990: in England and Wales this increase represents 13% of new births, in Scotland 20% and in Northern Ireland 27%. Clearly, the changes have been proportionally greater in Scotland and Northern Ireland, but these countries started from a lower baseline.

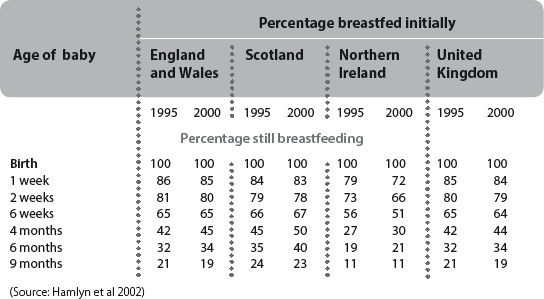

The prevalence of breastfeeding also indicates positive changes since 1995 (see Table 10.2). However, it is important to note that breastfeeding drops dramatic-ally after 6 weeks and that these figures include babies who are receiving other forms of nourishment as well as breast milk. Again, health benefits over time are difficult to extract unless exclusive breastfeeding is counted and identified as the independent variable. Finally, the ONS measures duration of breastfeeding, which is defined as the length of time a baby is breastfed from initiation to weaning, but again includes other forms of nutrition. The figures suggest that there has been a small decrease from 21% to 19% of babies across the UK who continue to receive breast milk at 9 months of age. However, the differences between UK countries is not so marked between 6 and 9 months, except that Northern Ireland babies appear to stop feeding dramatically after 6 months compared with the rest of the UK. Unfortunately, data are not systematically collected beyond this period so there is little national evidence of the effects of long-term breastfeeding. (These data will be available for 2005 with the full report due for publication in Spring 2007.)

The ONS/IC survey also provides an interpretation of the data that demonstrates significant positive correlations between incidence, prevalence and duration of breastfeeding and social class, age and education of the mother. Overall, younger mothers from lower social economic groups who completed their education by 16 are less likely to initiate breastfeeding than older, longer-educated women from better-off backgrounds. This is true across all UK countries, particularly Scotland and Northern Ireland. The Acheson report (DH 1999b) on inequalities in health identified the differences in prevalence in breastfeeding among different social groups and called for policies to address these differences. This was subsequently re-emphasised by HM Treasury and the Department of Health in the cross-cutting review of inequalities in health (DH/Treasury 2002), which recognised that promoting breastfeeding was one way in which infant morbidity and mortality rates among the most disadvantaged in our society could be improved. Interestingly, evidence from a study undertaken by the Institute of Education (Dex & Joshi 2005) has found that mothers from black and ethnic minority groups are more likely to breastfeed their babies for longer than white women, even when low income is taken into account. Their longitudinal study of 19 000 children born in 2000 and 2001 found that 49.4 of white mothers breastfed their infants for at least a month, compared to 68.6 of Indian mothers, 67.1% of Bangladeshi mothers and 82% of black mothers.

In order to address pubic health targets adequately, these breastfeeding data are critical to the interpretation and understanding of local health needs within primary care trusts and strategic health authorities, alongside other correlates of health improvement, such as smoking behaviour and teenage pregnancy. To realise the necessary health improvements, account has to be taken by public health analysts and practitioners of the co-variates affecting health behaviour and, ultimately, public health outcomes. The positive changes in breastfeeding rates should be correlated with other health data and some epidemiologists – notably Howie and colleagues (1990) – have conducted some rigorous analyses of these possible relationships.

Public health benefits of breastfeeding

Across the world, it has been estimated that over a million babies per year die from diarrhoea as a result of unsafe formula-feeding techniques, and that babies who are bottle-fed in poor conditions are 25 times more likely to die than breastfed babies (Baby Milk Action 2006, citing WHO). In relation to gastroenteritis, Bauchner (1986) found from a review of over 40 studies since 1970, that breastfeeding had a protective effect. Howie (1990), in a study of 618 children in Dundee, found that babies who breastfed for 13 weeks were not only protected from gastroenteritis but also that the benefits lasted for up to 1 year.

Breastfeeding has also been identified as a protective factor in sudden infant death syndrome (Savage 1992) and shown to be important in protection in the longer term from diseases such as Crohn’s disease (Kolezko et al 1989) coeliac disease (Akobeng et al, 2006) and insulin-dependent diabetes (Metcalf et al 1992). Clearly, the initiation and continuation of breastfeeding should lead to significant health gains and cost savings within the health services. These studies have been ground breaking in setting a pubic health agenda around breastfeeding and in recent years have been supplemented by a series of systematic reviews that have found unequivocal evidence for the pubic health benefits of breastfeeding and for exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months of age.

Most of the evidence on the public health benefits of breastfeeding is predicated on its relationship with the reduction of risk for certain diseases for either baby or mother. However, an alternative approach to public health is to consider the health promoting effects rather than the disease prevention effects of an intervention on its own. The White Paper Choosing health (DH 2004a) referred to areas for health improvement and outlined proposals for a ‘third way’ of both man-aging and preventing ill health. The paper acknowledged the social and economic causes of ill health, recognising that there are real inequalities in health, confirmed in Tackling inequalities in health (DH/Treasury 2002). The White Paper sets out to achieve public health improvements through reductions in smoking, improving diet and nutrition and preventing obesity, promoting mental health and promoting sexual health. Such initiatives are linked to serious diseases such as cancer and heart disease, but Choosing health sets out a series of salutagenic proposals that, if fully implemented, would promote and improve the conditions within which people make health choices, not just warn of the risks of disease associated with that choice. For example, nutritional improvements were located within a whole series of initiatives within schools and nursery schools, including free fruit for 4 to 6-year-olds and the development of the Healthy Schools Standard (DfES 2004), and Healthy Start (DH/NHS 2005) that replaces the Welfare Food Scheme by introducing vouchers that can be exchanged for healthy foods (full roll-out of this initiative expected by the end of 2006.) Improvements in mental health were considered in the light of many determinants, such as age of young men dying from suicide and postnatal depression, alongside social disadvantage and deprivation. Social support and advice for young parents, such as Sure Start and the development of Children’s Centres and Children’s Trusts, were also recognised in Choosing health as being crucial to the improvement of public health.

In the public spending review of 2005, the government introduced Public Service Agreements (PSAs) across all departments on which they are to deliver. For example, the Department of Health (DH) introduced a PSA target to halt the year on year increase in obesity among children under 11 by 2010. Recent indications suggest that this target will not be met. One in four children is obese, the Health and Social Care Information Centre (Health and Social Care Information Centre 2005) survey of 2000 children found: from 1995 to 2004, obesity among boys aged 11-15 rose from 14% to 24% and girls from 15% to 26%. The rate rose slightly in the 2-10 age group. Interestingly, the DH also introduced a PSA target that breastfeeding would increase by 2% per year:

Health gains of breastfeeding for infants

As already indicated, there has been much research conducted into the ways in which babies can benefit from breast milk; not all of which is conclusive. However, two published reports of a prospective study conducted in Dundee have found some convincing findings about the public health benefits of breastfeeding for infants. The first of these was published in 1990 (Howie et al 1990) and reported on the relation between breastfeeding and infant illness in the first 2 years of life, with particular reference to gastroenteritis. The study was based on a prospective, observational design of 750 pairs of mothers and infants of whom 618 were followed up for 24 months after birth. The infants were observed in detail at 2 weeks and at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21 and 24 months by health visitors. This regularity of surveillance minimised detection bias, as did rigorous definitions of the diseases being observed for and the ways in which the health visitors were instructed to ask parents questions. Gastrointestinal illness, for example, was defined as vomiting or diarrhoea or both lasting as a discrete illness for 48 hours or more. The main outcome measure was the prevalence of gastrointestinal disease in infants during the follow-up. Women were categorised for the purposes of the study by their breastfeeding behaviour at 13 weeks as either full breastfeeders (n=97), partial breastfeeders (n=130), early weaners (n=180) or bottle feeders (n=257). This was a helpful distinction as several previous studies had not made any attempt to define breastfeeding. The results showed that there were 50 episodes of gastrointestinal illness among bottle fed babies compared to two among fully breastfed babies. When these data was adjusted for variables such as social class and parental smoking, it was found that there was a significant difference in the prevalence of gastrointestinal illness at 13 weeks between babies who were either fully or partially breastfed and those who were bottle fed. There was also evidence that other illnesses were less prevalent among the breastfed babies, for example, respiratory illness was also less common. These benefits were observed to persist up to the first year of life, with fewer babies who were breastfed requiring admission to hospital with gastrointestinal illness. The authors point out that nothing in their study undermines the view that babies should be fully breastfed for 4-6 months. However, they do emphasise that some mothers either decide to bottle feed from the outset or give up breastfeeding prematurely because of the pressures of returning to work. They urge that women should be enabled to breastfeed for a minimum of 3 months through statutory maternity rights and crèche facilities at work. This recommendation is significant in the light of the historical overview at the beginning of this chapter. Interestingly, the Green Paper Our healthier nation (DH, 1998) did refer to the idea of the healthy workplace and enjoined employers to consider a contract for health, which included issues such as child-care facilities. It is a matter of some considerable interest that this did not feature strongly in either of the subsequent policy documents Saving lives (DH 1999a) or Choosing health (DH 2004a) and, therefore, there is no real policy incentive for employers to consider child-friendly environments that include time out to breastfeed or express milk. It is on such important matters for women that health visitors, midwives and other community nurses should be commenting and lobbying government, using the evidence provided by research, such as Howie et al’s, to support their arguments.

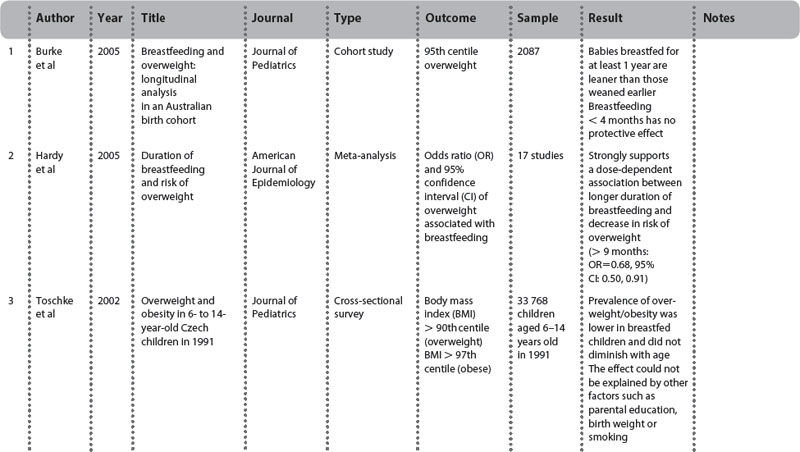

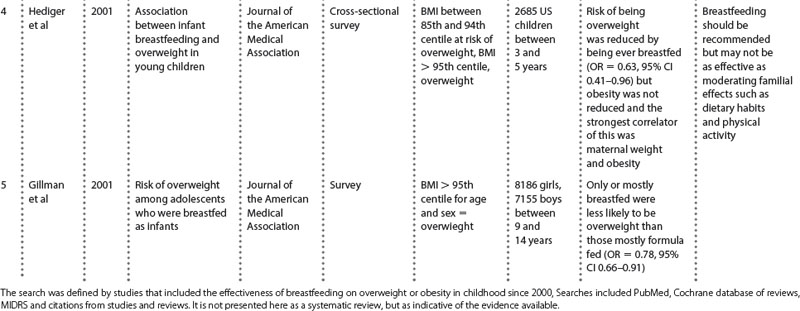

The importance for public health of Howie et al’s (1990) paper lies in its methodological rigour and significance of its findings, which clearly have implications for cost evaluation also, although the researchers do not carry out this exercise themselves. Eight years after the publication of this work, the researchers published their findings of the 7-year follow-up of the same cohort of infants (Wilson et al 1998). This type of long-term follow-up is unusual as it is costly, but it provides strong evidence on the benefits of breastfeeding. In this stage of the study the team analysed the relationship between infant feeding practices and childhood respiratory illness, growth, body composition and blood pressure. Of the original 674 children in the cohort, 545 were available for the study, the mean age of whom was 7.3 years. Outcome measures were prevalence of respiratory illness, height, body mass index, percentage body fat and blood pressure. Parents of the children were asked to complete a questionnaire about childhood illnesses and family history of allergy (545 or 81% of the original cohort) at around the age of 7 years and anthropometric measures including blood pressure, body composition, percentage body fat, skinfold thickness, weight and body mass index and height were completed by 412 or 61% of the original cohort. The same definitions of breastfeeding and the data were used as for the original study. The main findings from this study have important implications for child health, as they confirm that breastfeeding infants exclusively up to at least 15 weeks does confer health benefits into later childhood. For example, there is a significant reduction in respira-tory illness during the first 7 years of life for exclusively breastfed infants and exclusive formula feeding is associated with higher blood pressure (mean difference 3 mmHg systolic blood pressure) at the age of 7 and the early introduction of solids is associated with increased weight, percentage body fat and risk of wheezing in childhood. As the authors point out, the observed effects on body composition and blood pressure of bottle feeding and early solids may be magnified over time and become important antecedents of adult health. This again is significant in the light of the policy plans to reduce childhood obesity and the risks of diseases associated with obesity. The findings from Wilson et al’s (1998) study do confirm the advice of the WHO (2001) to continue breastfeeding for up to 6 months. It would, therefore, be appropriate for practitioners to utilise the evidence from Wilson et al’s (1998) study to support their own arguments to promote, audit and evaluate breastfeeding practice within their own localities. Since the publication of Wilson’s study, further evidence has emerged regarding the protective effects of breastfeeding against obesity and the cost benefits to the health care system of such an effect. Examples of such evidence are presented in Table 10.3 for ease of reference. Whilst the evidence presented here meets the criteria for high-quality evidence (Cochrane Collaboration 2006), the reader is advised to follow-up the cit-ations for full access to the individual studies.

Table 10.3 Summary of evidence of the protective effects of breastfeeding against obesity in childhood

It can be seen from Table 10.3 that the evidence on overweight and obesity is equivocal, although there is a definite tendency towards longer-term breastfeeding being protective against overweight and obesity. One of the problems with the evidence, to date, is that trials use different samples, outcome measures and different definitions of breastfeeding and duration, thus it is difficult to be absolute about the conclusion. For example, the Gilman (2001) study was based on a sample of over 15 000 young people up to the age of 14 whereas the Hediger (2001) study was based on a sample of 2685 children between 3 and 5 years who were more ethnically diverse. Perhaps Hediger’s study did not find such a strong re-lationship between breastfeeding duration and obesity because the sample was too small to show such an effect, or the effects do not become apparent until later childhood. However, the published systematic reviews would suggest that there is a benefit and the larger surveys, such as the Czech survey (Toschke et al 2002), certainly demonstrate that breastfeeding is worth promoting to protect children against obesity. This should be sufficient evidence in itself for health policy makers to consider ways in which breastfeeding could be promoted given the global public health problems that are arising from overweight and obesity in childhood. The cost benefit of breastfeeding to a health system would be significant if all the consequences of obesity, such as the treatment of type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease, could be costed and shown to be off-set by breastfeeding. An American study (Weimer 2001) has estimated that $3.6 billion (bn) would be saved if current breastfeeding rates could be raised from 64% in hospital to 75%, and from 29% at 6 months to 50%. This is based on cost savings from the treatment of three childhood diseases: otitis media, gastroenteritis and necrotising enterocolitis. Whilst obesity is not included in this analysis, it can be seen that the cost benefits might be huge if this were also evaluated in this way.

The overall cost of obesity to the NHS is currently around £1 bn, with a further £2.3 bn to £2.6 bn for the economy as a whole, it is proposed. Current UK breastfeeding rates (see Tables 10.1 and 10.2) remain below the US Surgeon General’s recommended rates (above) if the full cost benefit to public health is to be realised.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree