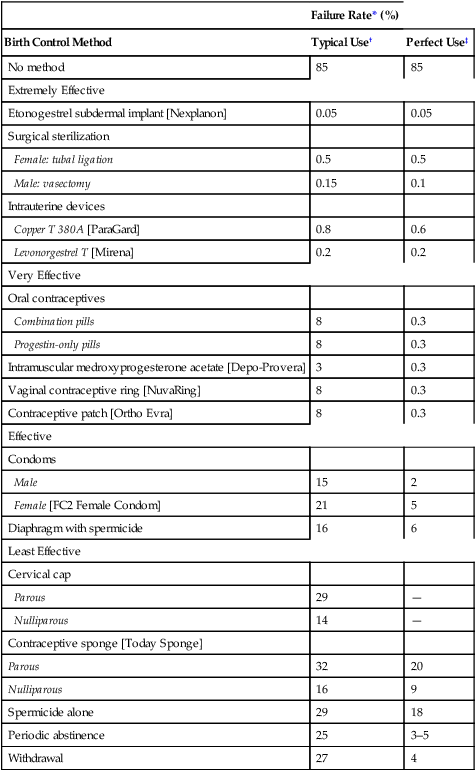

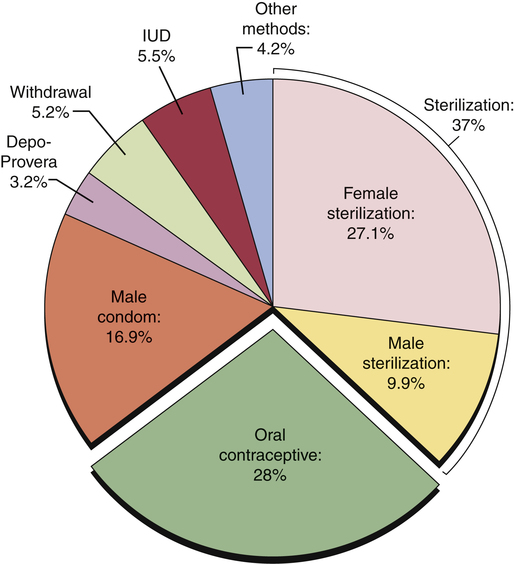

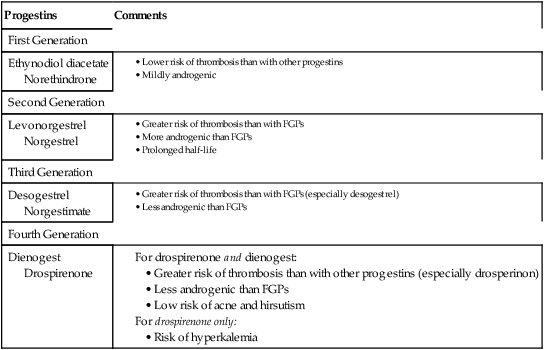

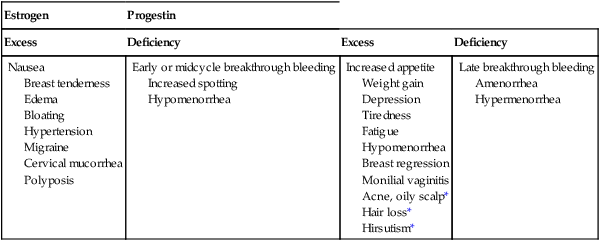

CHAPTER 62 Most of this chapter focuses on combination oral contraceptive pills—the most widely used reversible form of contraception. Sterilization is used more often, but is not reversible. In preparing to study these agents and other forms of contraception, you should review Chapter 61, paying special attention to information on the menstrual cycle and the physiologic and pharmacologic effects of estrogens and progestins. The effectiveness of a birth control method can be expressed as the percentage of unplanned pregnancies that occur while using the method. Employing this criterion, Table 62–1 compares the effectiveness of the major birth control methods. As you can see, the most effective methods are Nexplanon, intrauterine devices (IUDs), and sterilization. Oral contraceptives (OCs), Depo-Provera, the contraceptive ring, and the contraceptive patch are close behind. The least reliable methods include barrier methods, periodic abstinence, spermicides, and withdrawal. TABLE 62–1 Effectiveness of Birth Control Methods *Failure rate: percentage of women who have an unplanned pregnancy during first year of use. †Typical use: failure rate usually observed in actual practice. ‡Perfect use: failure rate that would be expected if the birth control method were practiced exactly as it should be. Note that Table 62–1 contains two columns of figures, one labeled perfect use and the other typical use. The perfect use figures represent pregnancy rates when a method of birth control is employed exactly as it should be (ie, consistently and with proper technique). The typical use figures represent pregnancy rates observed in actual practice. The higher pregnancy rates reported in the typical use column are largely an indication that methods of birth control are not always used when and as they should be. Figure 62–1 indicates the percentage of users who select a particular form of birth control. Perhaps surprisingly, the method chosen most frequently is sterilization: female sterilization (tubal ligation) plus male sterilization (vasectomy) are selected by 37% of birth control users. OCs or male condoms are chosen by most of the remaining birth control users. Diaphragms, periodic abstinence, IUDs, and other techniques account for a small fraction of birth control use. Several factors should be considered when choosing a method of birth control. Chief among these are effectiveness, safety, and personal preference. As indicated in Table 62–1, the most effective methods are etonogestrel subdermal implants [Nexplanon], intramuscular medroxyprogesterone acetate [Depo-Provera], sterilization, and IUDs. Three other methods—OCs, the contraceptive ring [NuvaRing], and the contraceptive patch [Ortho Evra]—are close behind. The remaining methods—condoms, the sponge, diaphragm, cervical cap, spermicides, and periodic abstinence—must be used in a near-perfect fashion to afford any reasonable level of protection. To help women select the birth control method that suits them best, Planned Parenthood has created a step-by-step computerized selection tool, accessible online at www.plannedparenthood.org/all-access/my-method-26542.htm. This tool accounts for all of the factors noted above. Combination OCs employ eight different progestins, which can be grouped into four generations (Table 62–2). Progestins in all four generations are equally effective. Differences relate to side effects, especially thrombotic events, androgenic effects (acne, hirsutism, dyslipidemia), and hyperkalemia. TABLE 62–2 Progestins Used in Combination Oral Contraceptives As indicated in Table 62–1, OCs can be very effective. With perfect use, the failure rate is only 0.3%. However, with typical use, the failure rate is significantly higher: about 8%. Among women who are overweight, efficacy is somewhat reduced. Possible reasons include decreased blood levels of the hormones, sequestration in adipose tissue, and altered metabolism. However, even though efficacy of OCs is slightly reduced in overweight women, these drugs are still more reliable than most of the alternatives. Combination OCs can cause a variety of adverse effects. However, although many types of effects may occur, severe effects are rare. Hence, when compared with the serious risks associated with pregnancy and childbirth, the risks of OCs are low. Nonetheless, because OCs are usually taken by women who are healthy, and because OCs represent a potential health hazard (albeit small), we must take steps to minimize risk. To this end, a full medical history should be obtained. If the history reveals an absolute contraindication to OC use (Table 62–3), OCs should not be prescribed. In women with relative contraindications, OCs should be used with caution. Should candidates for OCs undergo a thorough physical examination? Possibly, but the need is questionable. TABLE 62–3 Absolute and Relative Contraindications to the Use of Combination OCs Absolute Contraindications Thrombophlebitis, thromboembolic disorders, cerebral vascular disease, coronary occlusion, or a past history of these conditions, or a condition that predisposes to these disorders Abnormal liver function Known or suspected breast cancer Undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding Known or suspected pregnancy Smokers over the age of 35 Relative Contraindications Hypertension Cardiac disease Diabetes History of cholestatic jaundice of pregnancy Gallbladder disease Uterine leiomyoma Epilepsy Migraine Several measures can help minimize thromboembolic phenomena. Specifically: • The estrogen dose in OCs should be no greater than required for contraceptive efficacy. • OCs containing drospirenone or desogestrel should generally be avoided. • OCs should not be prescribed for heavy smokers, women with a history of thromboembolism, or women with other risk factors for thrombosis. • OCs should be discontinued at least 4 weeks prior to surgery in which postoperative thrombosis might be expected. • Women should be informed about the symptoms of thrombosis and thromboembolism (eg, leg tenderness or pain, sudden chest pain, shortness of breath, severe headache, sudden visual disturbance) and instructed to consult the prescriber if these occur. When used by women who experience migraine headaches, OCs may increase the risk of thrombotic stroke. However, the absolute increase is low: only 8 cases per 100,000 women at age 20, and rising to 80 cases per 100,000 women at age 40. Because the risk is low, OCs are generally considered safe for women with migraine, provided they are under age 35, don’t smoke, and are healthy, and provided their headaches are not preceded by visual changes known as an aura (migraine with aura has a greater risk of stroke than migraine without aura). Migraine and its management are discussed at length in Chapter 30. Many of the mild side effects of combination OCs result from an excess or deficiency of estrogen or progestin. Effects that can result from an excess of estrogen include nausea, breast tenderness, and edema. Progestin excess can increase appetite and cause fatigue and depression. A deficiency in either hormone can cause menstrual irregularities. Side effects related to hormonal imbalance are summarized in Table 62–4. TABLE 62–4 The combination OCs in current use are listed in Table 62–5. As you can see, nearly all of these products contain the same estrogen: ethinyl estradiol. In contrast, eight different progestins are employed. Products in the table are listed in order of increasing estrogen content. The OCs with low estrogen are safer. As a rule, high-estrogen OCs are reserved for women taking drugs that induce P450. Products with unique properties are discussed immediately below. TABLE 62–5 Composition of Combination Oral Contraceptives

Birth control

Effectiveness of birth control methods

Failure Rate* (%)

Birth Control Method

Typical Use†

Perfect Use‡

No method

85

85

Extremely Effective

Etonogestrel subdermal implant [Nexplanon]

0.05

0.05

Surgical sterilization

Female: tubal ligation

0.5

0.5

Male: vasectomy

0.15

0.1

Intrauterine devices

Copper T 380A [ParaGard]

0.8

0.6

Levonorgestrel T [Mirena]

0.2

0.2

Very Effective

Oral contraceptives

Combination pills

8

0.3

Progestin-only pills

8

0.3

Intramuscular medroxyprogesterone acetate [Depo-Provera]

3

0.3

Vaginal contraceptive ring [NuvaRing]

8

0.3

Contraceptive patch [Ortho Evra]

8

0.3

Effective

Condoms

Male

15

2

Female [FC2 Female Condom]

21

5

Diaphragm with spermicide

16

6

Least Effective

Cervical cap

Parous

29

—

Nulliparous

14

—

Contraceptive sponge [Today Sponge]

Parous

32

20

Nulliparous

16

9

Spermicide alone

29

18

Periodic abstinence

25

3–5

Withdrawal

27

4

Selecting a birth control method

Percentage use for birth control methods, United States, 2006–2008.

Percentage use for birth control methods, United States, 2006–2008.

Note: The segment labeled “other methods” refers to Nexplanon, contraceptive patches, contraceptive ring, spermicides, cervical caps, female condoms, and other techniques. (Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Oral contraceptives

Combination oral contraceptives

Components

Progestins.

Progestins

Comments

First Generation

Ethynodiol diacetate

Norethindrone

Second Generation

Levonorgestrel

Norgestrel

Third Generation

Desogestrel

Norgestimate

Fourth Generation

Dienogest

Drospirenone

Effectiveness

Adverse effects

Thromboembolic disorders.

Stroke in women with migraine.

Effects related to estrogen or progestin imbalance.

Estrogen

Progestin

Excess

Deficiency

Excess

Deficiency

Nausea

Breast tenderness

Edema

Bloating

Hypertension

Migraine

Cervical mucorrhea

Polyposis

Early or midcycle breakthrough bleeding

Increased spotting

Hypomenorrhea

Increased appetite

Weight gain

Depression

Tiredness

Fatigue

Hypomenorrhea

Breast regression

Monilial vaginitis

Acne, oily scalp*

Hair loss*

Hirsutism*

Late breakthrough bleeding

Amenorrhea

Hypermenorrhea

Preparations

Trade Name

mcg

Estrogen

mg

Progestin

28-DAY-CYCLE OCs

Monophasic

Loestrin Fea

10

Ethinyl estradiol

1

Norethindrone

Junel 1/20

20

Ethinyl estradiol

1

Norethindrone

Junel Fe 1/20

Loestrin 21 1/20

Loestrin Fe 1/20

Loestrin 24 Feb

Microgestin 1/20

Microgestin Fe 1/20

Aviane-28

20

Ethinyl estradiol

0.1

Levonorgestrel

Lessina

Lutera

Sronyx

Gianvic

20

Ethinyl estradiol

3

Drospirenone

YAZc

Beyazc,d

Generess Fee

25

Ethinyl estradiol

0.8

Norethindrone

Levora

30

Ethinyl estradiol

0.15

Levonorgestrel

Nordette-28

Portia-28

Cryselle

30

Ethinyl estradiol

0.3

Norgestrel

Low-Ogestrel-21

Low-Ogestrel-28

Lo/Ovral-28

Junel 1.5/30

30

Ethinyl estradiol

1.5

Norethindrone

Junel Fe 1.5/30

Loestrin 21 1.5/30

Loestrin Fe 1.5/30

Microgestin 1.5/30

Microgestin Fe 1.5/30

Apri

30

Ethinyl estradiol

0.15

Desogestrel

Desogen

Ortho-Cept

Reclipsen

Solia

Ocella

30

Ethinyl estradiol

3

Drospirenone

Safyrald

Yasmin

Kelnor 1/35

35

Ethinyl estradiol

1

Ethynodiol diacetate

Zovia 1/35

Balziva

35

Ethinyl estradiol

0.4

Norethindrone

Femcon Fee

Ovcon-35e

Zenchent

Brevicon-28

35

Ethinyl estradiol

0.5

Norethindrone

Modicon-28

Necon 0.5/35

Nortrel 0.5/35

Necon 1/35

35

Ethinyl estradiol

1

Norethindrone

Norinyl 1 + 35

Nortrel 1/35

Ortho-Novum 1/35

MonoNessa

35

Ethinyl estradiol

0.25

Norgestimate

Ortho-Cyclen-28

Previfem

Sprintec

Ovcon-50

50

Ethinyl estradiol

1

Norethindrone

Ogestrel 0.5/50

50

Ethinyl estradiol

0.5

Norgestrel

Zovia 1/50

50

Ethinyl estradiol

1

Ethynodiol diacetate

Necon 1/50

50

Mestranol

1

Norethindrone

Norinyl 1 + 50

Biphasic

Necon 10/11

35

Ethinyl estradiol

0.5

Norethindrone (phase 1)

35

Ethinyl estradiol

1

Norethindrone (phase 2)

Azurette

20

Ethinyl estradiol

0.15

Desogestrel (phase 1)

Kariva

10

Ethinyl estradiol

0

Desogestrel (phase 2)

Mircette

Triphasic

Caziant

25

Ethinyl estradiol

0.1

Desogestrel (phase 1)

Cesia

25

Ethinyl estradiol

0.125

Desogestrel (phase 2)

Cyclessa

Velivet

25

Ethinyl estradiol

0.15

Desogestrel (phase 3)

Aranelle

35

Ethinyl estradiol

0.5

Norethindrone (phase 1)

Leena

35

Ethinyl estradiol

1

Norethindrone (phase 2)

Tri-Norinyl

35

Ethinyl estradiol

0.5

Norethindrone (phase 3)

Ortho-Novum 7/7/7

35

Ethinyl estradiol

0.5

Norethindrone (phase 1)

Necon 7/7/7

35

Ethinyl estradiol

0.75

Norethindrone (phase 2)

Nortrel 7/7/7

35

Ethinyl estradiol

1

Norethindrone (phase 3)

Enpresse

30

Ethinyl estradiol

0.05

Levonorgestrel (phase 1)

Trivora

40

Ethinyl estradiol

0.075

Levonorgestrel (phase 2)

30

Ethinyl estradiol

0.125

Levonorgestrel (phase 3)

Ortho Tri-Cyclen Lo

25

Ethinyl estradiol

0.18

Norgestimate (phase 1)

Tri LoSprintec

25

Ethinyl estradiol

0.215

Norgestimate (phase 2)

25

Ethinyl estradiol

0.25

Norgestimate (phase 3)

Ortho Tri-Cyclen

35

Ethinyl estradiol

0.18

Norgestimate (phase 1)

TriNessa

35

Ethinyl estradiol

0.215

Norgestimate (phase 2)

Tri-Previfem

Tri-Sprintec

35

Ethinyl estradiol

0.25

Norgestimate (phase 3)

Estrostep Fe

20

Ethinyl estradiol

1

Norethindrone (phase 1)

Tilia

30

Ethinyl estradiol

1

Norethindrone (phase 2)

Tilia Fe

35

Ethinyl estradiol

1

Norethindrone (phase 3)

Tri-Legest Fe

Quadriphasic

Natazia

3

Estradiol valerate

0

Dienogest (phase 1)

2

Estradiol valerate

2

Dienogest (phase 2)

2

Estradiol valerate

3

Dienogest (phase 3)

1

Estradiol valerate

0

Dienogest (phase 4)

EXTENDED-CYCLE OCs

Introvalef

30

Ethinyl estradiol

0.15

Levonorgestrel

Jolessaf

Quasensef

Seasonalef

Seasoniqueg

LoSeasoniqueg

20

Ethinyl estradiol

0.1

Levonorgestrel

CONTINUOUS OC

Lybrelh

20

Ethinyl estradiol

0.09

Levonorgestrel ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree