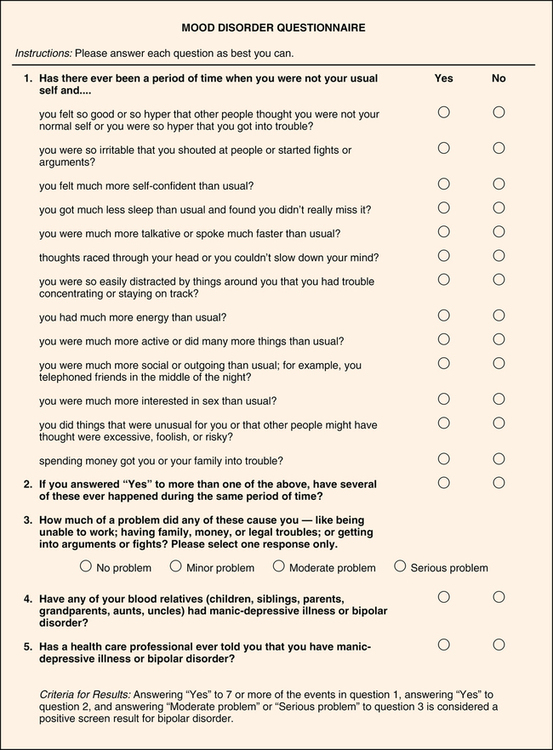

CHAPTER 13 1. Assess a patient with mania for (a) mood, (b) behavior, and (c) thought processes, and be alert to possible dysfunction. 2. Formulate three nursing diagnoses appropriate for a patient with mania, and include supporting data. 3. Explain the rationales behind five methods of communication that may be used with a patient experiencing mania. 4. Teach a classmate at least four expected side effects of lithium therapy. 5. Distinguish between signs of early and severe lithium toxicity. 6. Write a medication care plan specifying five areas of patient teaching regarding lithium carbonate. 7. Compare and contrast basic clinical conditions that may respond better to anticonvulsant therapy with those that may respond better to lithium therapy. 8. Evaluate specific indications for the use of seclusion for a patient experiencing mania. 9. Defend the use of electroconvulsive therapy for a patient in specific situations. 10. Review at least three of the items presented in the patient and family teaching plan (see Box 13-2) for a patient with bipolar disorder. 11. Distinguish the focus of treatment for a person in the acute manic phase from the focus of treatment for a person in the continuation or maintenance phase. Visit the Evolve website for a pretest on the content in this chapter: http://evolve.elsevier.com/Varcarolis Once commonly known as manic-depression, bipolar disorder is a chronic, recurrent illness that must be carefully managed throughout a person’s life. Bipolar disorder frequently goes unrecognized, and people suffer for years before receiving a proper diagnosis and treatment. Up to 21% of patients with major depression in primary care may actually have an undiagnosed bipolar disorder; lack of specific treatment for the bipolar disorder is associated with worse outcomes (Smith et al., 2011). Bipolar I disorder: Bipolar I is a mood disorder that is characterized by at least one week-long manic episode that results in excessive activity and energy (Angst et al., 2012). Manic episodes may alternate with depression or a mixed state of agitation and depression. Though people with bipolar I disorder may have periods of time when they may be symptom-free, it is such a severe disorder that the person experiencing it tends to have difficulty in maintaining social connections and employment. Psychosis (hallucinations, delusions, and dramatically disturbed thoughts) may occur during manic episodes. Additionally, the presence of three of the following behaviors constitutes mania: Inflated sense of self-importance Drastically reduced sleep requirements Excessive talking combined with pressured speech Personal feeling of racing thoughts Distraction by environmental events Unusually obsessed with and overfocused on goals Purposeless arousal and movement Bipolar II disorder: In bipolar II disorder, low-level mania alternates with profound depression. We call this low-level symptomatology hypomania. The hypomania of bipolar II disorder tends to be euphoric and often increases functioning. Like mania, hypomania is accompanied by excessive activity and energy for at least four days and involves at least three of the behaviors listed under mania. Unlike mania, psychosis is never present in hypomania although it may be present in the depressive side of the disorder (Mazzarini et al., 2010). The disorder is not usually severe enough to cause serious impairment in occupational or social functioning, and hospitalization is rare; however, the depressive symptoms tend to put those who suffer from it at particular risk for suicide. Cyclothymic disorder: Symptoms of hypomania alternate with symptoms of mild to moderate depression for at least two years in adults and one year in children. Neither set of symptoms constitutes an actual diagnosis of either disorder, yet the symptoms are disturbing enough to cause social and occupational impairment. As part of the spectrum of bipolar disorders, cyclothymic disorder may be difficult to distinguish from bipolar II disorder (Baldessarini et al., 2011). Individuals with cyclothymic disorder tend to have irritable hypomanic episodes. In children, cyclothymic disorder is marked by irritability and sleep disturbance (VanMeter et al., 2011). Some persons experience rapid cycling and may have at least four mood episodes in a 12-month period. The cycling can also occur within the course of a month or even a 24-hour period. Rapid cycling is associated with more severe symptoms, such as poorer global functioning, high recurrence risk, and resistance to conventional somatic treatments. It is estimated to be present in 12% to 24% of patients who go to specialized clinics for mood disorders (Bauer, 2008). Among children and teens bipolar disorder has a rate of about 1% (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2010). The lifetime risk, or the percentage of the population that will have a bipolar disorder by age 75, is 5.1% (Kessler, 2005). The median age of onset for bipolar I is 18 years; for bipolar II, the median age of onset is 20 years (Merikangas, 2007). Bipolar I tends to begin with a depressive episode—in women 75% of the time and in men 67% of the time (Sadock & Sadock, 2008). The episodes tend to increase in number and severity during the course of the illness. Women who experience a severe postpartum psychosis within two weeks of giving birth have a four times greater chance of subsequent conversion to bipolar disorder (Munk-Olsen et al., 2011). Researchers believe that giving birth may act as a trigger for the first symptoms of bipolar disorder, although few are diagnosed with this disorder during that episode. Hormone changes and sleep deprivation may be causative. Bipolar I disorder seems to be somewhat more common among males, but bipolar II disorder (characterized by the milder form of mania—hypomania—and increased depression), rapid cycling, mixed states, and depressive episodes are more common among females (Ketter, 2010). Women with bipolar disorders are more likely to abuse alcohol, commit suicide, and develop thyroid disease; men with bipolar disorder are more likely to have legal problems and commit acts of violence. Among adults, bipolar II disorder is believed to be underdiagnosed and is often mistaken for major depression or personality disorders, when it actually may be the most common form of bipolar disorder (Vieta & Suppes, 2008). Clinicians may downplay bipolar II and consider it to simply be the milder version of bipolar disorders; however, it is a source of significant morbidity and mortality, particularly due to the occurrence of severe depression. Anyone with major depression should be assessed for symptoms of hypomania since these symptoms are frequently associated with a progression to bipolar disorder (Fiedorowicz et al., 2011). One large-scale study with 9,282 participants revealed that more than half of people with bipolar disorder have another psychiatric disorder (Merikangas, 2007). Within a lifetime, the most commonly co-occurring disorders for all bipolar disorders were panic attacks (62%), alcohol abuse (39%), social phobia (38%), oppositional defiant disorder (37%), specific phobia (35%), and seasonal affective disorder (35%). Substance use disorders were much higher in bipolar I than in bipolar II disorders. Substance abuse and bipolar disorder should be treated at the same time whenever possible. The incidence of borderline personality disorder occurring along with bipolar disorder is high. Patients who have borderline personality disorder have a 19.4% higher rate of bipolar disorder than do people with other personality disorders (Gunderson, 2006). An important consideration is that this combination may result in higher levels of impulsiveness and aggressiveness and may be a risk factor for suicidality (Carpiniello et al., 2011). Bipolar disorders are thought to be distinctly different from one another; for example, bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, and cyclothymic disorder have different characteristics. Other variants of bipolar disease, including a number of other diseases whose end result is bipolar symptomatology, are currently being evaluated (Baum, 2008). When the disorder starts in childhood or during the teen years, it is called early-onset bipolar disorder and is more severe than the forms that first appear in older teens and adults (Birmaher et al., 2006). Young persons with bipolar disorder have more frequent mood switches, have more mixed episodes, are sick more often, and are at a greater risk of suicide attempts. Episodes of depression in bipolar disorders are different from unipolar depression (i.e., depression without episodes of mania—refer to Chapter 14). Depressive episodes in bipolar disorder affect younger people, produce more episodes of illness, and require more frequent hospitalization. They are also characterized by higher rates of divorce and marital conflict. The bipolar disorders have a strong heritability (i.e., the influence of genetic factors is much greater than the influence of external factors). Bipolar disorders are 80% to greater than 90% heritable whereas Parkinson’s disease, for example, is only 13% to 30% heritable (Burmeister, McInnis, & Zollner, 2008). The rate of bipolar disorders may be as much as 5 to 10 times higher for people who have a relative with bipolar disorder than the rates found in the general population. It is likely that bipolar disorder is a polygenic disease, which means that a number of genes contribute to its expression. In a landmark study at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), researchers found a connection between bipolar disorder and a genome that encodes an enzyme called diacylglycerol kinase eta (DGKH). Lithium is the first-line therapy for bipolar disorder, and DGKH is a crucial part of a lithium-sensitive pathway (Baum, 2008). Other research has focused on abnormal circadian genes that may result in a superfast biological clock, which manifests itself in extreme insomnia (McClung, 2007). Genetically, rapid cyclers tend to look a bit different. The circadian clock gene CRY2 is associated with rapid cycling in bipolar disorder (Sjöholm et al., 2010). The scientific community has been increasingly drawn to the concept of bipolar disorders and schizophrenia having similar genetic origins and pathology (Ivleva, 2010). Both disorders exhibit irregularities on chromosomes 13 and 15. It may be that the genotype has more to do with the specific expression of psychoses (altered thought, delusions, and hallucinations) than is reflected in traditional classification systems. Current psychiatric diagnostic systems will undoubtedly be modified as advances are made in molecular genetics, which will revolutionize our understanding and treatment of many psychotic disorders. Brain pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder are located in subregions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and medial temporal lobe (MTL). Dysregulation in the neurocircuits surrounding these areas has been viewed through functional imaging (e.g., positron emission tomography [PET] scans, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]). Neuroimaging studies reveal structural and functional brain changes in people with bipolar disorder. Some structural changes seem to cause the disorder, and some seem to be caused by the disorder. For example, prefrontal cortical changes are evident in the early stages of the illness whereas lateral ventricle abnormalities develop with repeated episodes of mania and/or depression (Strakowski, 2005). Functional imaging also reveals differences in the anterior limbic regions of the brain, which are associated with emotion, motivation, memory, and fear—the areas most deeply affected by bipolar disorder (Bora et al., 2011). The hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid-adrenal (HPTA) axis has been closely scrutinized in people with mood disorders. Hypothyroidism is known to be associated with depressed moods and is seen in some patients experiencing rapid cycling. In patients with treatment-resistant bipolar disorder, a high-dose thyroxine may be considered (Chakrabarti, 2011). Figure 13-1 presents the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ). This is not a definitive diagnostic test; however, it is a helpful initial screening device. The onset of bipolar disorder is often preceded by comparatively high cognitive function; however, there is growing evidence that about one third of patients with bipolar disorder display significant and persistent cognitive problems and difficulties in psychosocial areas. Cognitive deficits in bipolar disorder are milder but similar to those in patients with schizophrenia. Cognitive impairments are greater in bipolar I but are also present in bipolar II (Torrent, 2006). The potential cognitive dysfunction among many people with bipolar disorder has specific clinical implications (Robinson, 2006): • Cognitive function affects overall function. • Cognitive deficits correlate with a greater number of manic episodes, history of psychosis, chronicity of illness, and poor functional outcome. • Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent illness progression, cognitive deficits, and poor outcome. • Medication selection should consider not only the efficacy of the drug in reducing mood symptoms but also the cognitive impact of the drug on the patient. A primary consideration for a patient in acute mania is the prevention of exhaustion and death from cardiac collapse. Because of the patient’s poor judgment, excessive and constant motor activity, probable dehydration, and difficulty evaluating reality, risk for injury is a likely and appropriate diagnosis. Table 13-1 lists potential nursing diagnoses for bipolar disorders. TABLE 13-1 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS, NURSING DIAGNOSES, AND OUTCOMES FOR BIPOLAR DISORDERS Herdman, T.H. (Ed.). Nursing diagnoses—Definitions and classification 2012-2014. Copyright © 2012, 1994-2012 by NANDA International. Used by arrangement with John Wiley & Sons Limited. Table 13-1 lists associated outcomes for bipolar disorders. Specific outcome criteria will be based on which of the three phases of the illness the patient is experiencing.

Bipolar and related disorders

![]() http://coursewareobjects.elsevier.com/objects/ST/halter7epre/index.html?location=halter/four/thirteen%0d

http://coursewareobjects.elsevier.com/objects/ST/halter7epre/index.html?location=halter/four/thirteen%0d

Clinical picture

Epidemiology

Comorbidity

Etiology

Biological factors

Genetic

Neurobiological

Neuroendocrine

Application of the nursing process

Assessment

General assessment

Cognitive function

Diagnosis

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

NURSING DIAGNOSES

OUTCOMES

Hyperactivity, locomotion into unauthorized spaces, pacing, poor judgment

Wandering

Risk for injury

Remains in secure area when unaccompanied, can be redirected from unsafe activities, free from injury

Loud, profane, hostile, combative, aggressive, demanding behaviors

Risk for other-directed violence

Refrains from harming others, controls impulses, avoids violating others’ space

Anxiety, agitation, inability to concentrate, restlessness, prolonged periods of time without sleep

Sleep deprivation

Sleeps 5-8 hours a night, reports feeling rejuvenated after sleep

Poor reality testing, gradiosity, denial of problems, difficulty organizing and attending to information, poor concentration, inability to meet basic needs

Defensive coping

Ineffective coping

Reports an increase in concentration, refrains from manipulative behavior, uses effective coping strategies

Minimal nutritional intake, poor hygiene, clothing unclean

Self-care deficit (feeding, bathing, dressing)

Returns to precrisis level of care: Completes meals, tends to hygiene, dresses in clean clothing

Giving away of valuables, neglect of family, impulsive major life changes (divorce, career changes), stress and frustration of family members

Interrupted family processes

Caregiver role strain

Family obtains adequate resources to meet the needs of members; family routine is reestablished

Pressured speech, flight of ideas, going from one person or event to another, annoyance or taunting of others, loud and crass speech, provocative behaviors

Impaired verbal communication

Impaired social interaction

Initiates and maintains goal-directed and mutually satisfying verbal exchanges

Outcomes identification

Bipolar and related disorders

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access