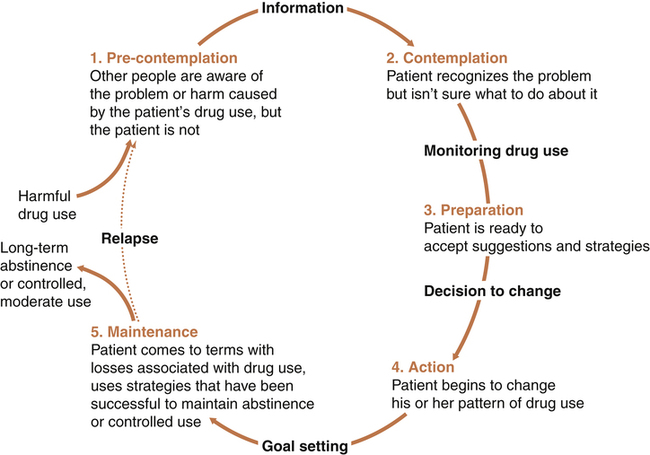

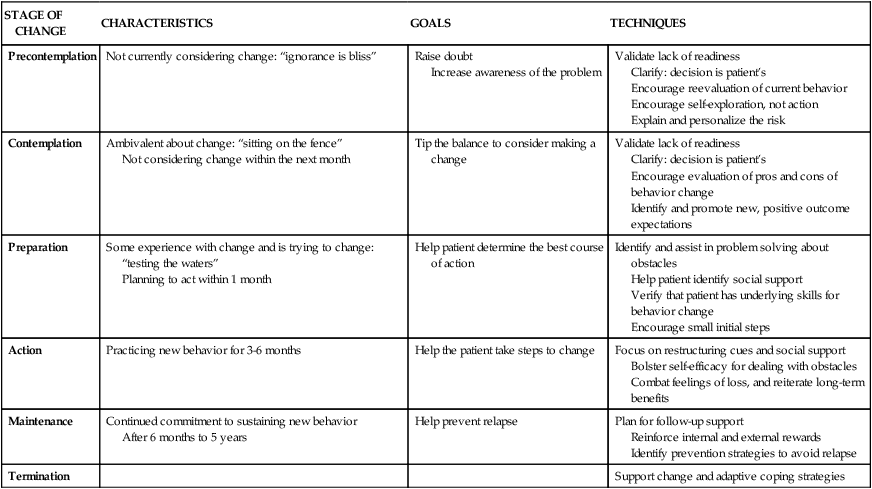

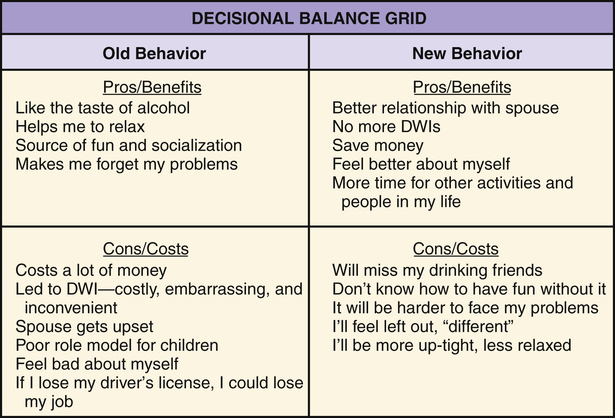

1. Describe behavior and behavior change strategies, including readiness to change and motivational interviewing and motivational interventions. 2. Examine the role of cognitions in adaptive and maladaptive coping responses. 3. Describe characteristics of cognitive behavioral interventions. 4. Identify elements of a cognitive behavioral assessment. 5. Apply the cognitive behavioral change interventions of cognitive restructuring and learning new behavior in nursing practice. 6. Analyze the role of the nurse in cognitive behavioral change interventions. Research has shown that cognitive behavioral interventions are effective in reducing symptoms and relapse rates with or without medication in a wide range of clinical problems, particularly depression, anxiety, eating disorders, personality disorders, and schizophrenia (Dobson, 2010; Ledley et al, 2010). They can be used in any treatment setting and have much to contribute to nursing practice. Nurses can use the following principles to guide their behavior change interventions: • All change is self-change. Patients are the active participants and primary agents of change. Nurses and other health care providers are the coaches, not the doers. • Self-efficacy is critical. Patients need to feel that they are in control of their own lives and accept responsibility for their efforts. All patients have strengths. • Knowledge does not equal change. Education is only one part of the change process. Patients need to transfer what they know into the actions they take. • A therapeutic alliance helps patients initiate and maintain change. The responsive and action dimensions of the nurse-patient relationship (Chapter 2) are critical ingredients for change. • Hope is essential. All effective interventions are based on the positive and hopeful expectations that life can be better (Stuart, 2010). The only reason people change their behavior is because they want to do so. Readiness to change is tied to a person’s motivation or what is referred to as motivational readiness. A central element in increasing motivation and eventual behavioral change is to take into account the person’s readiness to change. Behavior change occurs in stages over time (Prochaska et al, 1992; Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2008). Patients are more likely to engage in behavior change when their provider assesses their readiness for change and tailors their interventions accordingly. Table 27-1 summarizes these stages of change. Figure 27-1 shows the stages of change model applied to substance use disorders. TABLE 27-1 Motivation to change comes from within the individual. Without the desire or motivation to change, a person will not change one’s behavior. Motivational interviewing is a patient-centered, directive counseling method for enhancing a person’s internal motivation to change by identifying, exploring, and resolving ambivalence (Rollnick et al, 2008). The four key elements of motivational interviewing are as follows: 1. Express empathy. Acceptance of the patient facilitates change. Ambivalence is normal, and the use of reflective listening expresses understanding. 2. Identify the discrepancy. Ask the patient about the pros and cons of changing. Change is motivated by perceived discrepancy between present behaviors and important goals and values. 3. Roll with resistance. Avoid arguing about change. Offer new perspectives, but remember that the patient is the primary resource to identifying problems and finding solutions. It is helpful to emphasize personal choice and control. 4. Support self-efficacy. Belief in the possibility of change and hope in the future are important motivators. The patient is responsible for choosing and carrying out change; however, the clinician’s belief in the patient’s ability to change can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. • Feedback regarding personal risk or impairment is given to the patient after assessment of the problem. • Responsibility for change is placed explicitly on the patient, with respect for the patient’s right to make personal choices. • Advice about changing problematic behavior is given to the patient clearly and nonjudgmentally by the clinician. • Menus of self-directed change options and treatment alternatives are offered. • Empathic counseling—showing warmth, respect, and understanding—is emphasized. • Self-efficacy—or optimistic empowerment—is fostered in the patient to encourage change. Decisional balance exercises are specific ways that the clinician can assist the patient to explore the pros and cons of old and new behaviors for the purpose of tipping the scales toward a decision for positive change. The items are identified by the patient with gentle help from the clinician and then written in a grid. This is shown in Figure 27-2 for a patient who has an alcohol use problem. The four blocks of the grid add a new twist to the traditional two-column “pros and cons” list. Cognition is the act or process of knowing. Cognitive strategies are based on the thinking that it is not the events themselves that cause anxiety and maladaptive responses but rather people’s expectations, appraisals, and interpretations of these events. They suggest that maladaptive behaviors can be altered by dealing directly with a person’s thoughts and beliefs (Beck, 1976, 1995). For example, someone may consistently view life in an unrealistically positive way and thus take dangerous chances, such as denying health problems and claiming to be “too young and healthy for a heart attack.” Cognitive distortions also may be negative, such as those expressed by a person who interprets all unfortunate life situations as proof of a complete lack of self-worth. Common cognitive distortions are listed in Table 27-2. TABLE 27-2

Behavior Change and Cognitive Interventions

Behavior Change Strategies

Readiness to Change

STAGE OF CHANGE

CHARACTERISTICS

GOALS

TECHNIQUES

Precontemplation

Not currently considering change: “ignorance is bliss”

Raise doubt

Increase awareness of the problem

Validate lack of readiness

Clarify: decision is patient’s

Encourage reevaluation of current behavior

Encourage self-exploration, not action

Explain and personalize the risk

Contemplation

Ambivalent about change: “sitting on the fence”

Not considering change within the next month

Tip the balance to consider making a change

Validate lack of readiness

Clarify: decision is patient’s

Encourage evaluation of pros and cons of behavior change

Identify and promote new, positive outcome expectations

Preparation

Some experience with change and is trying to change: “testing the waters”

Planning to act within 1 month

Help patient determine the best course of action

Identify and assist in problem solving about obstacles

Help patient identify social support

Verify that patient has underlying skills for behavior change

Encourage small initial steps

Action

Practicing new behavior for 3-6 months

Help the patient take steps to change

Focus on restructuring cues and social support

Bolster self-efficacy for dealing with obstacles

Combat feelings of loss, and reiterate long-term benefits

Maintenance

Continued commitment to sustaining new behavior

After 6 months to 5 years

Help prevent relapse

Plan for follow-up support

Reinforce internal and external rewards

Identify prevention strategies to avoid relapse

Termination

Support change and adaptive coping strategies

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational Interventions

Cognitive Strategies

DISTORTION

DEFINITION

EXAMPLE

Overgeneralization

Draws conclusions about a wide variety of things on the basis of a single event

A student who has failed an examination thinks, “I’ll never pass any of my other exams this term, and I’ll flunk out of school.”

Personalization

Relates external events to oneself when it is not justified

“My boss said our company’s productivity was down this year, but I know he was really talking about me.”

Dichotomous thinking

Thinking in extremes—that things are either all good or all bad

“If my husband leaves me I might as well be dead.”

Catastrophizing

Thinking the worst about people and events

“I’d better not apply for that promotion at work because I won’t get it and then I’ll feel terrible.”

Selective abstraction

Focusing on details but not on other relevant information

A wife believes her husband doesn’t love her because he works late, but she ignores his affection, the gifts he brings her, and the special vacation they are planning together.

Arbitrary inference

Drawing a negative conclusion without supporting evidence

A young woman concludes “my friend no longer likes me” because she did not receive a birthday card.

Mind reading

Believing that one knows the thoughts of another without validation

“They probably think I’m fat and lazy.”

Magnification/minimization

Exaggerating or trivializing the importance of events

“I’ve burned the dinner, which goes to show just how incompetent I am.”

Perfectionism

Needing to do everything perfectly to feel good about oneself

“I’ll be a failure if I don’t get an A on all my exams.”

Externalization of self-worth

Determining one’s value based on the approval of others

“I have to look nice all the time or my friends won’t want to have me around.” ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access