expert practitioners. Acute low back problems are defined as activity intolerance resulting from lower back or back-related leg symptoms of shorter than 6 weeks’ duration. Evidence and recommendations found in this guideline form the basis for the conservative care of the patient with acute low back pain outlined in this chapter.

TABLE 18-1 “RED FLAGS” TO RECOGNIZE IN THE HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF PATIENTS WITH NECK OR BACK PAIN | |

|---|---|

|

Rule out signs or symptoms of potentially dangerous underlying conditions, that is, “red flags”; see Table 18-1.

Collect a detail-focused history emphasizing limits to normal lifestyle, functional loss (including bladder and bowel dysfunction), and degree of pain.

Perform a regional back examination (e.g., deformity, vertebral point tenderness, muscle spasm).

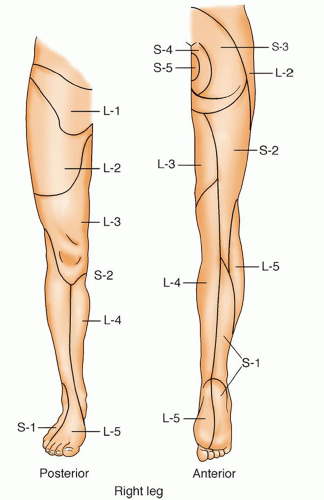

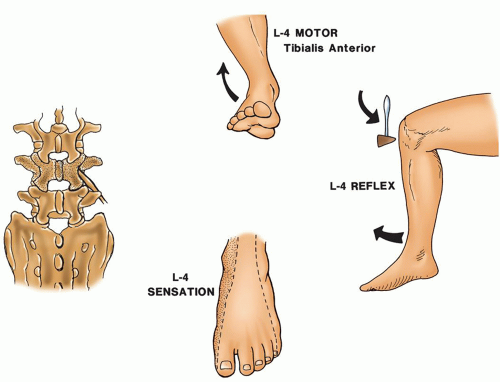

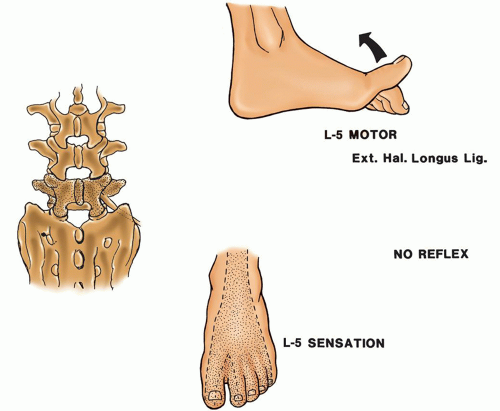

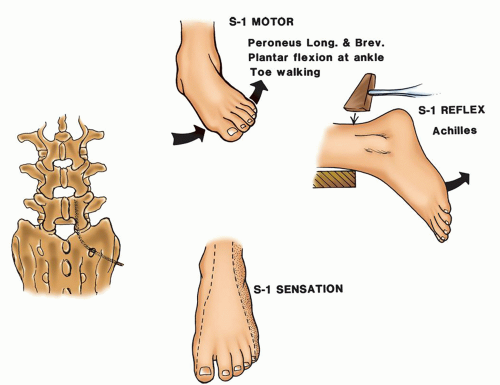

Perform a neurological screening examination with particular attention to muscle strength, sensory dermatomes (pinprick and light touch), reflexes, evidence of muscle atrophy, flexibility (forward bending), and observation of the patient walking (e.g., posture, on toes, on heels, squat).

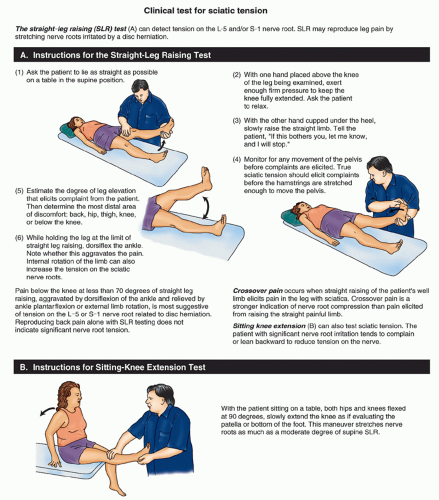

Perform the straight-leg raising test for low back pain (sometimes called Lasègue’s sign); Figure 18-5 shows a way of testing for sciatic nerve root tension.

Gradually reintroduce activities as symptoms improve. Walking; gentle, gradual stretching; sitting for only short periods of time; and changing positions frequently are recommended.

Ice alternating with heat, or whichever is preferred, may help decrease inflammation. Advise not to apply ice for more than 20 minutes of every hour and ensure heating pads are at a safe temperature.14

Instruct on core strengthening and low back stabilization exercises.

Stress will increase back pain. Take measures to decrease stress.

Constipation will increase back pain; constipation prevention should not be overlooked.

TABLE 18-2 CONDITIONS RELATED TO SPINAL PAIN | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

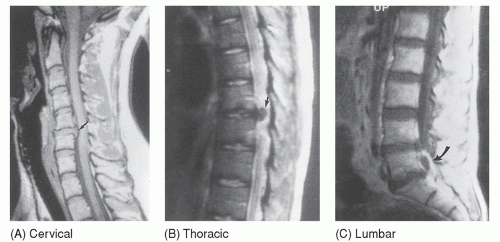

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the “gold standard” for diagnosis of neural and soft-tissue problems (Fig. 18-6).

Nerve conduction studies are ordered to evaluate for nerve compromise (radiculopathy) if the radiographic study, history, and clinical examination do not correlate and further diagnostic study is warranted.

Other laboratory tests (e.g., erythrocyte sedimentation rate, complete blood count, and urinalysis) are helpful to screen for nonspecific medical problems; a bone scan is helpful if a spinal cord tumor, infection, or occult fracture is suspected. Generally, this would be completed with the initial evaluation if “red flags” are present.

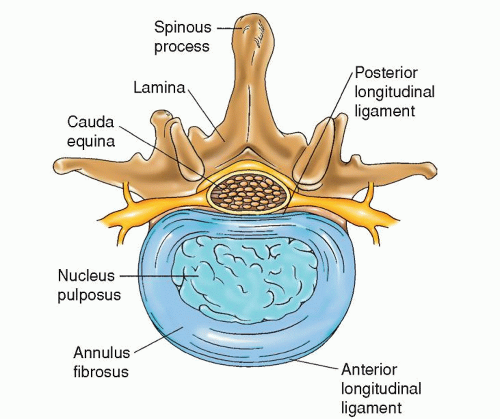

Figure 18-1 ▪ Axial view of the lumbar spine, showing an intervertebral disc, the contents of the spinal canal, and the elements of the posterior bony arch. |

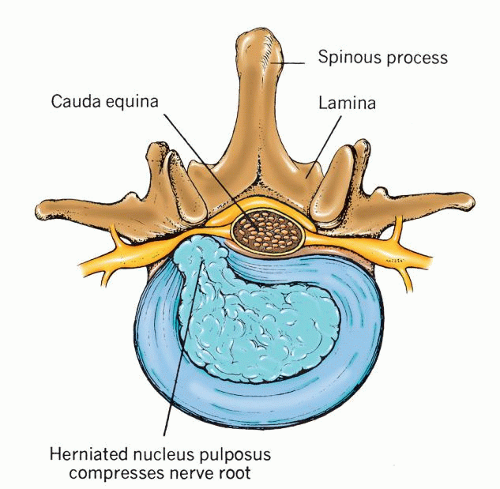

Figure 18-2 ▪ Ruptured vertebral disc. (From: Chaffee, E. E., & Lytle, I. M. [1980]. Basic physiology and anatomy. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott.) |

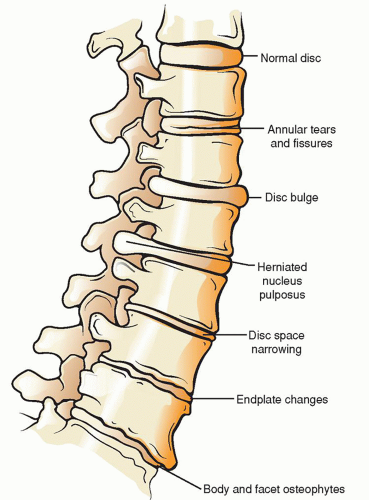

Figure 18-3 ▪ The degenerative cascade. (From: Jeong, G. K., & Bendo, J. A. [2004]. Spinal disorders in the elderly. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 425, 110-125.) |

of the foot may be evident. The patient has difficulty walking on the toes. The hamstring muscles may also show signs of weakness. If atrophy is present, the gastrocnemius and the soleus muscles are affected. The ankle-jerk reflex is often diminished or absent.

Figure 18-8 ▪ L-4 neurologic level. (From: Scherping, S.C. [2004]. History and physical examination. In: Frymoyer, J. W. & Wiesel, S. W. [Eds.]. The adult and pediatric spine [3rd ed., pp. 49-68]. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.) |

TABLE 18-3 NEUROLOGICAL LEVELS OF THE LOWER EXTREMITIES25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Figure 18-9 ▪ L-5 neurologic level. (From: Scherping, S.C. [2004]. History and physical examination. In: Frymoyer, J. W. & Wiesel, S. W. [Eds.]. The adult and pediatric spine [3rd ed., pp. 49-68]. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.) |

to C-7 levels, with pain along the affected sensory dermatomes. Anatomically, there is little free room within the spinal canal to accommodate any extraneous material. The cervical spinal cord is firmly positioned by the ligamenta denticulata. Disc protrusion in the cervical area can result not only in root compression but also in cord compression because of the lack of free space. The particular presenting symptoms depend on the anatomic point and degree of disc protrusion.

Figure 18-10 ▪ S-1 neurologic level. (From: Scherping, S.C. [2004]. History and physical examination. In: Frymoyer, J.W. & Wiesel, S.W. [Eds.]. The adult and pediatric spine [3rd ed., pp. 49-68]. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree