a Assign severity based on the most severe category in which any feature occurs.

b Based on recall over a 2- to 4-week period.

c Risk factors: either one of the following: physician-diagnosed atopy, parental history of asthma, evidence of sensitization to aeroallergens, or two of the following: evidence of sensitization to foods, eosinophilia (≥4%), or wheezing apart from colds.

SABA, short-acting beta agonist; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FEV1/FVC, forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; N/A, not applicable.

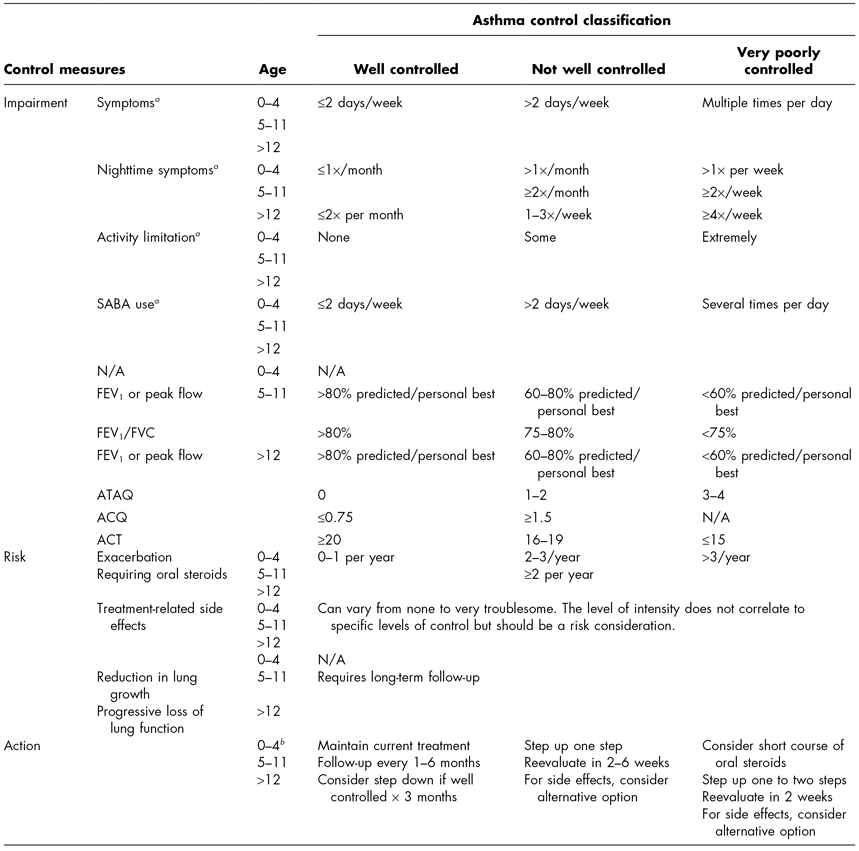

Table 7.2 Asthma control and therapy adjustment.

Adapted from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR3).

a Based on recall over a 2- to 4-week period.

b If not well controlled or very poorly controlled and there is no clear benefit in 4–6 weeks, consider an alternative diagnosis or adjusting therapy.

SABA, short-acting beta agonist; ATAQ, Asthma Therapy Assessment Questionnaire©; ACQ, Asthma Control Questionnaire©; ACT, Asthma Control Test™; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FEV1/FVC, forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced vital capacity ratio.

In addition to performing spirometry upon initial evaluation to help determine asthma severity, spirometry should also be performed on a regular basis to assess the level of control. The EPR3 recommends performing spirometry at the initial assessment, after treatment is initiated and symptoms and peak expiratory flow rates (PEFRs) have stabilized, during periods of poor asthma control, and at least every 1–2 years (NHLBI, 2007).

Other tests that should be obtained as needed to rule out alternative diagnoses include chest X-ray, additional pulmonary function tests, bronchoprovocation studies, allergy/immunology testing, and biomarkers of inflammation.

Chest X-Ray

A chest X-ray should be ordered if not previously obtained to rule out other diagnoses such as foreign body obstruction. Radiographic findings of the child with asthma may be normal or may reveal hyperinflation or peribronchial cuffing. If there is mucus retention, atelectasis may be present (Novelline, 2004).

Additional Pulmonary Function Tests

Lung volumes may be obtained. An elevated total lung capacity (TLC) is consistent with asthma and airway obstruction. A decreased TLC is diagnostic of restrictive lung disease and alternative diagnoses should be considered. Inspiratory loops may be useful when considering the diagnosis of vocal cord dysfunction.

Bronchoprovocation Studies

Bronchoprovocation or challenge studies may be helpful when children have symptoms consistent with asthma but have normal spirometry results. Two well-known bronchoprovocation tests include exercise and methacholine challenge testing (MCT). An exercise challenge test is indicated when symptoms occur with exercise. It can be performed in children greater than age 6. It involves obtaining baseline spirometry and heart rate followed by 4–6 minutes of maximal exercise (80–90% maximal heart rate for age) on a treadmill or bicycle ergometer. After the cessation of exercise, serial spirometry measurements are obtained. If there is a greater than 10% drop in FEV1, it is a positive finding (American Thoracic Society, 1999). For MCT, baseline spirometry is again obtained. Methacholine (a chemical that increases parasympathetic tone in bronchial smooth muscles) is then administered via inhalation in varying concentrations. Spirometry is obtained after each dose of methacholine. A positive test is defined as a 20% decrease in FEV1 from baseline or after the last dose of methacholine. This measure is known as the provocative concentration or PC20% (American Thoracic Society, 1999). MCT has a higher sensitivity than exercise challenge testing. Because bronchospasm may be induced with testing, the facility should be properly equipped with emergency medications and supplies such as albuterol, epinephrine, and supplemental oxygen. A newer bronchoprovocation study using mannitol is also available.

Allergy and Immunology Testing

If allergies are being considered in the differential diagnosis, testing should be performed by blood sampling (radioallergosorbent test [RAST]) or skin prick testing. These tests can be used to determine if the child is allergic to common indoor and outdoor allergens. An IgE level and complete blood count (CBC) should also be ordered. If an immune disorder is being considered, basic quantitative immunoglobulins should be obtained.

Biomarkers of Inflammation

Biomarkers of inflammation such as sputum eosinophils and fractional concentration of nitric oxide (fraction of exhaled nitric oxide [FeNO]) are being utilized in some practices. However, according the EPR3, they require further evaluation before they can be recommended as a clinical tool for asthma management (NHLBI, 2007).

Determining Severity

Once all other conditions have been ruled out and the child meets the diagnostic criteria for asthma, the health-care provider should classify the child’s level of asthma severity. Severity is defined as the intrinsic intensity of the disease process (NHLBI, 2007). To obtain the most accurate assessment of severity, it is best to assess the child before he/she initiates long-term control therapy. However, because this is not always possible, severity can be inferred from the least amount of medication therapy necessary to maintain control (NHLBI, 2007).

Severity should be based on the domains of current impairment and future risk. Impairment is defined as the frequency and intensity of symptoms and functional limitations the child is currently experiencing or has recently experienced (NHLBI, 2007). Determining a child’s current impairment requires an assessment of symptoms, nighttime awakenings, use of SABA for symptoms, exercise limitation, and lung function. Studies have demonstrated that the FEV1/FVC ratio appears to be a more sensitive measure of severity in the impairment domain (NHLBI, 2007). Risk is defined as the likelihood of either asthma exacerbations, progressive decline in lung function or reduced lung growth, or risk of adverse effects from medications (NHLBI, 2007). An assessment of future risk includes an evaluation of the frequency of asthma exacerbations requiring oral systemic corticosteroids. Studies have revealed that the FEV1 appears to be a useful measure for indicating risk for exacerbations (NHLBI, 2007).

The EPR3 lists four classifications of asthma severity: intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent, and severe persistent. Table 7.1 provides a chart to assist the health-care provider in determining asthma severity.

COMPLICATIONS

Asthma is associated with impaired quality of life, frequent utilization of acute care facilities, increased health costs, and missed school and work days (Guilbert et al., 2010). Inadequately treated asthma leads to impaired growth and weight gain and failure to thrive. Children with asthma have a higher incidence of psychological disorders including poor self-esteem, anxiety, and depression (Mrazek, 1992).

Asthma is associated with deterioration in lung function over time, which is exacerbated by smoking. This decrease in lung function may occur before the age of 2 years (Guilbert et al., 2004). Pathology has revealed evidence of remodeling in the airway wall with fibrosis and collagen deposition. There may be a link between asthma and the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults (Martinez, 2009).

Asthma, along with most chronic pulmonary diseases, increases the prevalence of GERD (Berquist et al., 1981). Asthma may worsen obstructive sleep apnea. It leads to an increase in postsurgical complications (Kalra, Buncher, & Amin, 2005). Asthma is associated with increased morbidity from viral infections, such as influenza (Gaglani, 2002), sickle cell disease (Sylvester et al., 2007), and cardiac disease.

Asthma medications may cause side effects. Corticosteroids, both inhaled and oral, are associated with a decrease in linear growth and adrenal suppression in a dose-dependent manner. Corticosteroids cause oral thrush. Daily use of oral corticosteroids may cause immunosuppression and an increased susceptibility to infection (Leone, Fish, Szefler, & West, 2003).

Asthma exacerbations may lead to death. Fatalities have been associated with one or more life-threatening events, poor symptom control, frequent emergency room visits, the use of oral corticosteroids, impaired perception of the severity of obstruction, poor socioeconomic status, and psychiatric disease (NHLBI, 2007). An asthma attack may precipitate dissection of air along tissue planes. Air can dissect into subcutaneous tissue (subcutaneous emphysema), pleural space (pneumothorax), mediastinum (pneumomediastinum), around the heart (pneumopericardium), and, rarely, into the spinal cord (pneumorrhachis). A pneumothorax or pneumopericardium can result in inadequate ventilation and oxygenation and decreased cardiac output and shock.

MANAGEMENT

The overall goals of asthma management are to reduce impairment and risk. This includes preventing chronic symptoms, limiting the use of SABA, maintaining normal or near-normal lung function and activity levels, meeting the patient’s/family’s expectations of care, preventing exacerbations, minimizing the need for ED visits and hospitalizations, preventing loss of lung function, preventing reduced lung growth (in children), and experiencing little to no side effects from therapy (NHLBI, 2007).

Allergen avoidance and pharmacotherapy are utilized in combination to control and prevent asthma symptoms. Both require an individualized approach. Two other fundamental components of asthma management are education (discussed in the section “Nursing Care of the Child and Family”) and the ongoing assessment of asthma contro1.

Allergen Avoidance

Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, also known as the dust mite (DM) is a common allergen and trigger of asthma symptoms. DMs thrive in humid environments and depend on human dander for their existence. Because there are high levels of DMs in mattresses, pillows, and bed covers, the child’s bed is the major focus of DM control (NHLBI, 2007). Washing linens weekly can help control DMs (Arlian, Vyszenski-Moher, & Morgan, 2003). Linens should be washed in hot water (>130°F). In addition, the mattress and pillows should be encased in allergen-impermeable covers (NHLBI, 2007). Other actions that can be instituted to control DMs include keeping indoor humidity between 30 and 50%, removing carpets, eliminating and/or minimizing stuffed toys, washing stuffed toys weekly, and avoiding lying on upholstered furniture (NHLBI, 2007).

Pet dander can also be an allergen and trigger for children with asthma. Recommendations for controlling animal antigens include bathing the pet regularly, keeping the pet out of the child’s bedroom, keeping the child’s bedroom door closed, and keeping the pet off of upholstered furniture. Of course, the ideal method of avoidance is to remove the pet from the home.

Outdoor allergens (tree, grass, and weed pollen, and mold such as Alternaria) can also trigger asthma symptoms. Avoidance measures include staying indoors with the windows closed and the air conditioner on during pollen season (NHLBI, 2007). Parents should be instructed to monitor pollen counts in their area. Other control measures include not hanging clothes outside on the line and having the child take a shower before going to bed if he/she was playing outdoors.

Smoking exposure is a common irritant and trigger of asthma symptoms (Gilliland et al., 2006). Reducing exposure is vital. Smoking should not be allowed in the car or at home.

Cockroach exposure is common in inner city areas and can be troublesome for children with asthma. Parents and children should be instructed to not leave food or garbage uncovered. To eliminate cockroaches, traps or boric acid are preferred. If chemical agents are necessary, the home should be well ventilated and the child should not return home until the odor has disappeared (NHLBI, 2007).

Pharmacotherapy

The primary goal of pharmacotherapy is to use an effective medication at the lowest dose possible to achieve control of symptoms and to reduce exacerbations. By doing so, one minimizes side effects and costs.

Asthma medications are divided into two categories: long-term control medications and quick-relief medications. Long-term control medications are used to achieve and maintain asthma control. They include the following drug classes: corticosteorids (ICSs and oral corticosteroids), cromolyn sodium, immunomodulators, leukotriene modifiers, LABAs, and methylxanthines. Quick-relief medications are used to treat acute symptoms and exacerbations. Quick-relief medications include anticholinergics, SABAs, and systemic corticosteroids (NHLBI, 2007). Specific medication classes, mechanisms of action, side effects, and names are discussed in Chapter 3. However, the following provides some general considerations for asthma pharmacotherapy. First, every child with asthma should be prescribed a SABA for rescue therapy to relieve symptoms of airflow obstruction. Second, a daily ICS is preferred for initiating therapy in infants and in young children (NHLBI, 2007). Findings have demonstrated the effectiveness of ICS in improving symptoms and in reducing exacerbations in infants and in children with asthma (Guilbert et al., 2006). The biggest concern that parents generally express is the potential effect on growth, which is temporary (Rottier & Duiverman, 2009). Parents should be reassured that in long-term studies with conventional dosing, the final growth was not affected (Agertoft & Pedersen 1994; Visser et al., 2004). Finally, omalizumab (anti-IgE antibody) therapy can be costly (Hendeles & Sorkness, 2007). Therefore, insurance and patient assistance programs should be investigated.

A stepwise approach to medication therapy is recommended to manage asthma (NHLBI, 2007). Table 7.1 provides a listing of the different steps and associated severity levels. The EPR 3 stepwise approach includes six steps and three different age groups (0- to 4-year-olds, 5- to 11-year-olds, and ≥12-year-olds). In all age groups, step 1 consists of as-needed use of a SABA to manage intermittent asthma. Steps 2–6 are used to manage persistent asthma and vary according to the age group and asthma severity level as outlined next:

- For children 0–4 years:

- Step 2. Low-dose ICS is preferred. Cromolyn or montelukast is an alternative.

- Step 3. Medium-dose ICS is preferred.

- Step 4. Medium-dose ICS plus either a LABA or montelukast are preferred.

- Step 5. High-dose ICS plus either a LABA or montelukast are preferred.

- Step 6. High-dose ICS plus either a LABA or montelukast and oral corticosteroids are preferred.

- Step 2. Low-dose ICS is preferred. Cromolyn or montelukast is an alternative.

- For children 5–11 years:

- Step 2. Low-dose ICS is preferred. Cromolyn, leukotriene receptor antagonist, nedocromil, or theophylline is an alternative.

- Step 3. Either low-dose ICS plus LABA, leukotriene receptor antagonist, or theophylline or medium-dose ICS is preferred.

- Step 4. Medium-dose ICS plus a LABA are preferred. Medium-dose ICS plus either leukotriene receptor antagonist or theophylline are alternatives.

- Step 5. High-dose ICS plus LABA are preferred. High-dose ICS plus either a leukotriene receptor antagonist or theophylline are alternatives.

- Step 6. High-dose ICS plus LABA plus oral corticosteroid are preferred. High-dose ICS plus either a leukotriene receptor antagonist or theopylline plus oral corticosteroid are alternatives.

- Step 2. Low-dose ICS is preferred. Cromolyn, leukotriene receptor antagonist, nedocromil, or theophylline is an alternative.

- For children ≥12 years:

- Step 2. Low-dose ICS is preferred. Cromolyn, leukotriene receptor antagonist, nedocromil, or theophylline is an alternative.

- Step 3. Either a low-dose ICS plus LABA or a medium-dose ICS is preferred. Low-dose ICS plus either leukotriene receptor antagonist, theophylline, or zileuton are alternatives.

- Step 4. Medium-dose ICS plus LABA are preferred. Medium-dose ICS plus either leukotriene receptor antagonist, theophylline, or zileuton are alternatives.

- Step 5. High-dose ICS plus LABA and consideration of omalizumab for patients with allergies are preferred.

- Step 6. High-dose ICS plus LABA and oral corticosteroids and consideration of omalizumab for patients with allergies are preferred (NHLBI, 2007).

- Step 2. Low-dose ICS is preferred. Cromolyn, leukotriene receptor antagonist, nedocromil, or theophylline is an alternative.

As health-care providers, it is important to remember that guidelines are not intended to replace clinical decision making. The stepwise approach is a fluid process that requires adjustment in treatment as necessary. The health-care provider should attempt to step down therapy if the child’s asthma is well controlled for at least 3 months (NHLBI, 2007). If the child’s asthma is not well controlled, a step-up in therapy may be necessary.

Not all symptoms are due to ineffective medication therapy. Other factors such as inhalation technique, adherence, allergen exposure, and comorbid conditions can play a significant role in the manifestation of symptoms. Therefore, before stepping up therapy, the health-care provider must assess inhaler technique as well as adherence to medications (pharmacy refill history and patient report are two methods that can be used to assess adherence). Furthermore, the environment should always be considered as a potential key factor. Parents should be asked if there have been any changes to their environment (i.e., new home/location, installation of carpeting, addition of pet, flooding, and presence of a live evergreen tree) recently or since the last visit. Information regarding changes to the environment may not be voluntarily reported by the parents or the child because such changes are part of normal everyday life and may not appear to them to be related to asthma. However, they can trigger asthma symptoms and should be assessed. Furthermore, identifying and treating comorbid conditions such as allergies, GERD, or sinusitis can positively influence asthma symptoms and eliminate the need for a step-up in therapy. A final consideration is the potential for aspirin sensitivity. Although more common in individuals of Eastern European and Japanese descent and rare in children, aspirin sensitivity can also worsen symptoms (Farooque & Lee, 2009). Generally, symptoms include profound rhinorrhea, tearing, and severe bronchospasm occurring within 1 hour of exposure. After confirmatory testing, these medications should be avoided.

Monitoring Control

In addition to allergen avoidance and pharmacotherapy, assessment of asthma control is an important component of asthma management. The level of control will dictate changes in medication therapy. Control is defined as the degree to which manifestations of asthma are minimized and goals are met (NHLBI, 2007). Like severity, control is also determined based on the domains of current impairment and future risk. Specific areas of assessment include symptoms, lung function, quality of life, history of exacerbations, adherence to and side effects caused by medications, patient–provider communication and satisfaction, and biomarkers of inflammation. Evaluation of these areas is based on parent/child recall over the past 2–4 weeks. Control is described as well controlled, not well controlled, and very poorly controlled. Table 7.2 provides the asthma control chart and recommendations for adjustment in therapy.

The EPR3 recommends that all children with asthma receive follow-up care every 2–6 weeks initially and when making adjustments in therapy. Once control is achieved, follow-up care should occur every 1–6 months to determine whether or not goals of therapy are being met (NHLBI, 2007).

Assessment of asthma control should also occur at home. Parents (and the child if old enough) should be instructed on how to monitor their asthma. In addition to assessing symptoms, children with moderate or severe persistent asthma, children with a history of severe exacerbations, and children who have difficulty perceiving airflow obstruction and worsening asthma may benefit from the use of a peak flow meter to assess asthma control at home (NHLBI, 2007). A peak flow meter is a handheld device used to measure the PEFR or the maximum flow rate than can be generated during a forced expiratory maneuver. The PEFR is a measure of the large airways (Yoos & McMullen, 1999). To use a peak flow meter, the child should be instructed to

- place the indicator at “0,”

- stand or sit up straight and tall,

- take a deep breath,

- place the mouthpiece in the mouth (behind teeth) with lips wrapped tightly around the mouthpiece, and

- blow fast and hard in a single breath.

The above steps will cause the indicator to move up the peak flow meter barrel. The corresponding number is the actual peak flow. The steps should be repeated for a total of three times. The highest of the three readings is the PEFR that should be recorded.

The PEFR readings are compared against the child’s peak flow zones and are used to self-manage asthma and to assess control in the home setting. The child’s peak flow zones should be based on his/her personal best or the predicted, whichever is higher. The personal best is the highest PEFR that the child can achieve over a 2- to 3-week period of time when his/her asthma is well controlled. The predicted is based on a chart of normal PEFRs and is based on height and sex. The peak flow zone system can be explained to parents and children using the traffic light analogy. The green zone (>80% of personal best or predicted) indicates that asthma is well controlled on current therapy. The yellow zone (50–80% of personal best or predicted) indicates that asthma is not well controlled and requires assessment and intervention such as the use of a SABA. The red zone (<50% of personal best or predicted) is considered the “danger zone” and requires immediate medical attention.

The peak flow meter is an effort-dependent device. Therefore, before taking action based on a single reading, the parents should assure that proper technique was used during the measurement. If the lips are not tightly placed around the mouthpiece, the values may be falsely low. Alternatively, if the child coughs or spits into the device, the values may be falsely high.

Managing Exacerbations

Although preventing exacerbations is a goal of asthma management, exacerbations continue to occur. In 2005, approximately 3.8 million children experienced an asthma exacerbation in the previous year (Akinbami, n.d.).

Exacerbations are also classified according to level of severity: mild-moderate (PEFR or FEV1 ≥ 40% predicted) or severe (<40% predicted). It is important to recognize that severe exacerbations can occur at any level of asthma severity; in other words, even those with intermittent asthma can have a severe exacerbation. Exacerbations are managed either at home or in the hospital, depending on their level of severity.

The focus of home asthma exacerbation management is early intervention (NHLBI, 2007). This focus further underscores the importance of teaching parents and children how to self-manage asthma. General home management includes knowing how to use an asthma action plan, recognizing early signs of an exacerbation, and removing allergens from the environment. During an exacerbation, the parent/child should promptly initiate SABA therapy, monitor response to therapy, and stay in contact with a primary care provider (PCP).

Initial home therapy includes the use of a SABA, up to two treatments (nebulizer or two to six puffs of the metered-dose inhaler [MDI] formulation), 20 minutes apart. If the child responds well to the SABA (no wheezing or dyspnea and PEFR in the green zone), the parents should contact the health-care provider for additional instructions. The child can use the SABA every 3–4 hours for 24–48 hours. In addition, the health-care provider may want to consider a short course of oral corticosteroids at this time. If the response to the initial SABA is incomplete (persistent wheezing or PEFR in the yellow zone), the parent should contact the health-care provider immediately so that oral steroids can be initiated. If the response to the initial SABA is poor (marked wheezing, dyspnea, or PEFR in the red zone), the child needs urgent evaluation. The health-care provider should be contacted immediately, the SABA should be repeated, and an oral steroid should be initiated. If the child is in distress, he/she should go directly to the ED or call 911 (NHLBI, 2007).

A severe exacerbation associated with a PEFR or FEV1 less than 40% predicted usually requires an emergency room visit and possible hospitalization. Children with severe status asthmaticus are at risk for sudden deterioration and respiratory arrest. They must be sequentially and frequently assessed by physical exam, FEV1 or PEFR if possible, and oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry (SpO2). Supplemental oxygen should be given, if necessary, to keep oxygen saturation ≥90%. Most providers keep oxygen saturation ≥95% in order to give the patient as much reserve as possible. High-dose inhaled SABA is given with ipratropium with MDI plus valved holding chamber every 20 minutes or via nebulization continuously for 1 hour. Oral corticosteroids should be given if the patient has not already received them. If there is no improvement after continued therapy and the PEFR or FEV1 remains under 70% predicted, then the patient should be admitted to the hospital. In-hospital therapy consists of supplemental oxygen, continued use of SABA, and corticosteroids. Intravenous hydration may be necessary if the patient has been unable to drink or eat. A PEFR or FEV1 less than 40% despite aggressive treatment will likely require admission to an intensive care unit. Signs of impending or actual respiratory failure include drowsiness, confusion, severe respiratory distress, and arterial carbon dioxide level (PCO2) ≥42 mm Hg. Adjunct therapies such as intravenous magnesium or heliox-driven albuterol nebulization may be considered. Intubation and mechanical ventilation may be necessary.

If the child is experiencing frequent exacerbations or is not meeting goals of therapy, the health-care provider should consider a referral to an asthma specialist. Other reasons to consider a referral to an asthma specialist are if the child is exhibiting atypical signs and symptoms, if there are problems with the differential diagnosis, or if additional testing is required (NHLBI, 2007).

NURSING CARE OF THE CHILD AND FAMILY

The primary role of the nurse is to provide education to the child and family so that they are able to self-manage the asthma. Education for the child with asthma and his/her family is an integral component of asthma management and the EPR3. National certification for asthma educators has been available since 2002 from the National Asthma Educator Certification Board (National Asthma Educator Certification Board, n.d.). Asthma self-management education programs have been proven effective. In a published meta-analysis, Coffman and colleagues revealed that providing asthma education in the pediatric setting decreases the mean number of ED visits and hospitalizations and the odds of an ED visit (Coffman, Cabana, Halpin, & Yelin, 2008). Other pediatric asthma education studies have also demonstrated an increase in asthma knowledge, self-efficacy, adherence, and quality of life, and a decrease in ED visits, hospitalizations, and costs when children and their parents participate in asthma self-management education programs (Butz et al., 2005; Greineder, Loane, & Parks, 1999; Kelly et al., 2000; Newcomb, 2006).

After the diagnosis of asthma is established, care should be given to the child and family to ensure that they have a basic understanding of asthma and how it is managed. The educational process should be comprehensive and ongoing. It should include all members of the health-care team and should occur across various settings.

Additionally, the nurse should develop a partnership with the parents and the child. This partnership includes the development of mutually agreed-upon treatment goals. The child should be involved as much as possible in establishing goals of therapy. The nurse must create an environment that encourages open communication. Such a relationship will allow the nurse to effectively assess barriers to care as well as adherence to treatment.

All patients should receive basic education regarding asthma in a culturally competent manner. The essential components of an educational program include basic facts about asthma, how to assess the level of control, how asthma is treated (this includes information about medications and allergen avoidance), how to use prescribed devices, how to respond to signs and symptoms of worsening asthma, and when and where to seek medical attention.

The educational plan should be individualized to meet the needs of the parents and child and should include the provision of an asthma action plan. Prior to providing the education, the nurse should make an assessment of what the parents and child already know about asthma. This evaluation provides the nurse with the opportunity to reinforce accurate messages and to correct inaccurate ones. The nurse should also determine how much information to provide at each setting so as not to overwhelm the parents and the child.

Basic Facts

When providing information about the basic facts, the nurse must emphasize the role inflammation plays in asthma. This will help the parents and child understand the purpose of the medications prescribed. The use of pictures or models is helpful.

Allergen/Trigger Avoidance

The parents and the child should receive individualized instruction and advice regarding environmental control measures (specific measures were discussed earlier in this chapter). Unfortunately, environmental control measures such as carpet removal or professional extermination services can be costly and are not covered by insurance companies. In such situations, the nurse should work with the family and refer them to resources that are available in the community. When discussing environmental control measures, the nurse should remember to include an assessment of the daycare and school environment as the child spends a great deal of time in those locations.

Respiratory viruses are a common trigger for asthma symptoms. In addition to practicing good hand washing, the parents should be encouraged to have their child (if not allergic to the vaccine or eggs) vaccinated with the influenza vaccine. The CDC recommends that children 6 months of age and older receive the influenza vaccine. Depending on the age of the child, either one or two doses may be required (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], n.d.,a). A recent univariate analysis found that the influenza vaccine reduced ED visits and use of oral steroids (Ong, Forester, & Fallot, 2009).

Medications and Delivery Devices

When providing information about medications, the nurse should include the name of the medication, the dose, the dosing interval, and the side effects. Because oral candidiasis is a potential side effect of ICSs, the parents and child should be instructed to have the child rinse his/her mouth after the ICS is administered. Another important fact to reinforce in regard to medications is the difference between long-term control medications and quick-relief medications.

Because most asthma medications are administered via inhalation, the nurse must ensure that the parents and child know and follow the correct technique and priming recommendations. This starts by making sure the most appropriate delivery device is selected for the child. The nurse plays an integral role in determining the most suitable device. Factors to consider when choosing a device include the child’s ability to use the device correctly, the preferences of the child for the device, the availability of the drug/device combination, the compatibility between the drug and the delivery device, convenience, durability, the cost of the device, and the potential for reimbursement (Dolovich et al., 2005).

Parents often assume a nebulizer is a more effective form of medication delivery; however, the MDI used with or without spacer/holding chamber is appropriate for the delivery of ICSs and SABAs at home, in the hospital, and in the ED (Dolovich et al., 2005). Previous studies have demonstrated that MDIs are as effective as nebulizers in treating individuals with asthma. However, data in the treatment of those experiencing severe exacerbations are not as strong (Castro-Rodriguez & Rodrigo, 2004). If the child is prescribed a nebulizer, the “blow-by” technique should be discouraged. Furthermore, if the child is not old enough to use a mouthpiece (with a nebulizer or a holding chamber), the nurse should fit the child for an appropriate-sized mask.

Inspiratory flow rates are also important when selecting a medication delivery device. If the child does not take a deep breath, the medicine will not adequately reach the lower airways. With MDIs, if the inhalation is too fast, the medication may be deposited in the back of the throat rather than in the lower airways. Having the child inhale slowly and deeply over a count of 10 (for a younger child, have him/her count to 10 with the fingers of his/her other hand) is the proper technique for an MDI. With dry powder inhalers (DPIs), if the inspiratory effort is weak/slow, the device will not be activated properly; this will have a negative impact on deposition to the lower airways. DPIs are more effective when the child inhales rapidly (Dolovich et al., 2005). An assessment of the inhaler technique can be made with the use of the In-Check DIAL. The In-Check DIAL is a handheld device used to measure inspiratory flow rate. This device and its use are described in Chapter 3.

Self-Management

The parents and child should be instructed on how to self-manage asthma at home. This is best accomplished with the use of an asthma action plan (Bhogal, Zemek, & Ducharme, 2006). The child should be involved in the development of the asthma action plan, and it should be written in terms that are understood by the parent and older child. Studies have demonstrated that keeping teaching materials simple and concise improves health-care knowledge (Paasche-Orlow et al., 2005).

Key elements of an asthma action plan include what to do on a daily basis, when to step up therapy, and when to contact the health-care provider. The asthma action plan should also include environmental control measures and contact telephone numbers for the health-care provider (NHLBI, 2007).

In a Cochrane Review evaluating symptom versus peak flow-based asthma action plans, no significant differences in rates of exacerbations requiring oral steroids or admissions, lung function, symptom scores, and quality of life were noted. Findings did reveal that children using symptom-based asthma action plans experienced a lower risk of exacerbations requiring an acute care visit. Furthermore, children preferred symptom-based plans. However, data were insufficient to recommend using one method over the other (Bhogal et al., 2006). Thus, asthma action plans can be based on symptoms and/or PEFR. If the plan is based on PEFRs, the nurse must ensure that the parent/child knows how to use the peak flow meter and how to respond to the readings. If the child is experiencing symptoms or a decrease in PEFRs (yellow or red zone), he/she should take action by adding a SABA to the daily medications and by contacting the health-care provider if the SABA does not relieve symptoms.

Adherence and Barriers to Care

The nurse must work with the child to determine if there are any barriers to carrying out the agreed-upon asthma action plan. Adherence to therapy has a major impact on asthma control. There are many factors that contribute to nonadherence. They can be patient related, caregiver related, or disease related. Examples include patient/family psychological disorders, lack of insurance, long wait times for appointments, inconvenient office hours, lack of communication with the health-care provider, medication side effects, and the need for daily therapy (Adams, Dreyer, Dinakar, & Portnoy, 2004). Forgetfulness is the primary reason identified for nonadherence (Matsui, 2007). If medication administration is difficult at home (i.e., the child wakes up late or forgets to take his/her medication), the nurse can work with the family and the school nurse to make arrangements to have the medications administered at school if possible.

The best way to assess adherence is to use a nonjudgmental approach. The nurse must remember that there may be underlying issues that the parents have not shared with the health-care provider (i.e., fear of ICS side effects, not knowing how to recognize symptoms, inability to give the medicine twice a day, not recognizing the need for daily medications). By communicating with the parents/child and addressing the concerns, adherence will likely improve (Williams et al., 2007).

Anticipatory Guidance

Anticipatory guidance is important for parents and children. Parents should be made aware that giving medications to infants, toddlers, and preschoolers can sometimes be difficult. For oral medications, the nurse should prepare the parents by informing them that the younger child may try to spit out the medication because of the taste. Some medications can be flavored by the pharmacy; parents should be instructed to check with their local pharmacy to determine if this option is available.

For inhaled medications, the nurse should provide the parents with developmentally appropriate methods (demonstrating medication administration on the child’s favorite doll, allowing the child time to touch and explore the mask, holding chamber, etc., employing distractions such as singing to the child) to help ensure adequate medication delivery. The parent should be reassured that any difficulty with medication administration is related to developmental maturity level and will resolve as the child becomes accustomed to the device.

School-related issues also require attention. The nurse should encourage the parents to discuss the fact that their child has asthma with the school nurse and teachers. The nurse should also ensure that the school is provided with a copy of the written asthma action plan, a SABA plus a nebulizer or holding chamber (often called spacer), and an authorization for medication administration. If the child is old enough, the nurse should work with the family and other health-care providers to allow the child the ability to carry his/her own SABA while in school. If this is allowed by the school system, written instructions for the school, along with parental permission to carry the SABA, are necessary. Easy access is key to early intervention. The NAEPP has partnered with various organizations to ensure that children are allowed to carry their own medications. Legislation has been enacted by a number of states to allow for self-administration (NHLBI, 2007).

Physical activity at home and in school should be promoted. Parents sometimes limit their child’s activities because they are afraid the exercise will exacerbate their child’s asthma. However, parents should be made aware that children with asthma can and should exercise. The child himself/herself should also be encouraged to participate in physical activities. If needed, treatment with a SABA before exercise can be prescribed to prevent symptoms of exercise-induced bronchoconstriction.

Finally, there are a number of organizations that provide educational materials to people with asthma as well as health-care providers. Parents should be informed about the existence of these organizations and should be provided with their contact information. Helpful resources include

- Allergy & Asthma Network Mothers of Asthmatics

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree