Assisting in Urology and Male Reproduction

Learning Objectives

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary.

2. Apply critical thinking skills in performing the patient assessment and patient care.

3. Describe the anatomy and physiology of the urinary system.

4. Explain the susceptibility of the urinary system to diseases and disorders.

5. Identify the primary signs and symptoms of urinary problems.

6. Detail common diagnostic procedures of the urinary system.

7. Compare and contrast infections and inflammations of the urinary system.

8. Describe urinary tract disorders and cancers.

9. Distinguish between the two methods of treating renal failure.

10. Summarize the typical pediatric urologic disorders.

11. Identify the male organs of reproduction.

12. Determine the causes and effects of prostate disorders.

13. Outline common types of genital pathologic conditions in men.

14. Perform patient education for the testicular self-examination.

15. Analyze the effects of sexually transmitted infections in men.

16. Summarize the characteristics of HIV infection and the diagnostic criteria and treatment protocols.

17. Describe the medical assistant’s role in urologic and male reproductive examinations.

Vocabulary

albuminuria (al-byu-muh-nur-e′-uh) The abnormal presence of albumin protein in the urine.

azotemia (a-zo-te′-me-uh) The retention of excessive quantities of nitrogenous wastes in the blood.

copulation Sexual intercourse.

creatinine (kre′-a-tuhn-en) Nitrogenous waste from muscle metabolism that is excreted in urine.

dysuria Painful or difficulty urination.

erythropoietin (i-rith-ruh-poi-e′-tuhn) A substance released by the kidneys and liver that promotes red blood cell formation.

Kaposi’s sarcoma A malignant tumor of endothelial cells that begins as brown or purple papules on the feet and slowly spreads in the skin.

urgency A sudden, compelling desire to urinate and the inability to control the release of urine.

wasting syndrome Physical deterioration resulting in profound weight loss, fatigue, anorexia, and mental confusion.

Scenario

Sara Ricci, a CMA (AAMA) with 10 years’ experience, works for Dr. Samuel Fineman, a urologist who also manages male reproductive disorders. Dr. Fineman relies on Sara to handle telephone calls from patients, to have a clear understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the renal system, and to assist him in the clinical area of the practice. Although Sara has worked for Dr. Fineman for almost 2 years, occasionally problems still arise that she is not sure how to manage. Sara attends workshops and conferences to earn continuing education units to maintain her CMA credential and tries to choose topics that focus on urologic issues. In addition, she keeps up to date on new diagnostic procedures and treatments for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Sara helps train other medical assistants in the practice and makes sure adequate patient education supplies are available for self-testicular examination.

While studying this chapter, think about the following questions:

Urology is the study of the urinary tract in both male and female patients. A physician who specializes in the diseases and disorders of the urinary system is a urologist. Urologists also specialize in conditions associated with the male reproductive system.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Urinary System

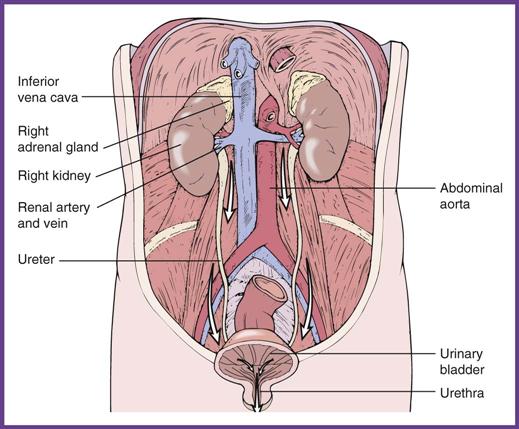

The urinary tract consists of bilateral kidneys and ureters, the urinary bladder, and the urethra (Figure 40-1). The main function of the urinary system is to remove waste products from the body. Waste materials are byproducts of the body’s metabolic processes, and if left to accumulate in the bloodstream, they can become toxic. The urinary system removes salts and nitrogenous wastes (nitrogen is the product of protein metabolism) from the blood, forming urea, which is excreted. Besides excreting waste material, the urinary system performs other functions, such as:

• Helping to maintain homeostasis by regulating water, electrolyte, and acid-base levels

• Activating vitamin D, which is needed for calcium absorption

• Producing erythropoietin, which helps control the rate of red blood cell formation

• Helping to maintain blood pressure by secreting the enzyme renin

The kidneys are red-brown, bean-shaped glandular organs. They are located posterior to the peritoneum (retroperitoneal) and against the muscles of the back, roughly between the T12 and L3 vertebrae. The left kidney is situated about 1 inch (2 cm) higher than the right because of the location of the liver.

The kidneys remove unwanted substances from the blood and form urine for excretion. For this crucial function, a great deal of blood circulates through the kidneys—approximately 15% to 30% of the total cardiac output. The blood is delivered to the two kidneys by the renal artery and is distributed through the kidneys by a highway of smaller arteries. The blood then is returned through a pathway of veins, including the renal vein, which flows into the inferior vena cava in the abdominal cavity.

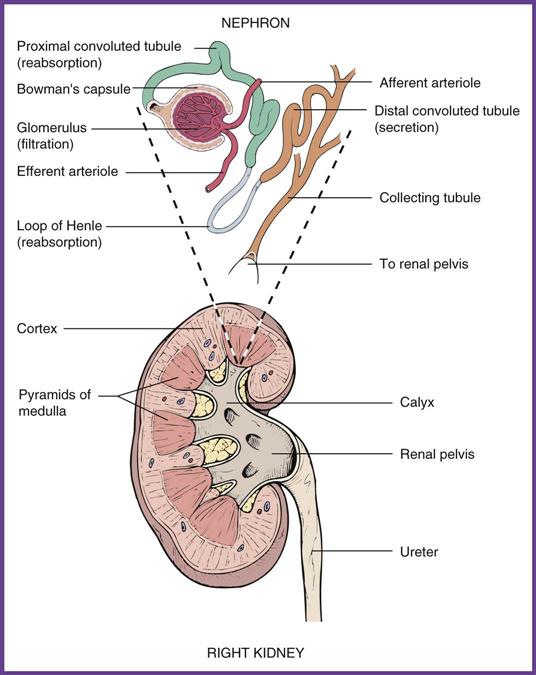

The outer layer of the kidney, the cortex, contains the functional unit of the kidney, the nephron, where urine is formed as fluid and dissolved substances move between its vascular and tubular structures. Three processes are involved in urine formation: filtration, reabsorption, and excretion. The nephron consists of the glomerulus, a cluster of capillaries extending from the distal renal artery that is partly surrounded by Bowman’s capsule. Fluid and dissolved substances are filtered from the glomerulus to Bowman’s capsule and then into the proximal convoluted tubules, where most of the fluid is reabsorbed by venules and arterioles surrounding the tubules and sent back into the general circulation. Based on the homeostatic needs of the body, the kidneys determine the type and quantity of substances that are reabsorbed. Finally, the remaining substances are excreted through the distal convoluted tubules to the collecting tubules and then on to the medulla of the kidney. The medulla contains the renal pelvis, where the urine is deposited before passing down the ureters. The distal collection area of the renal pelvis is made up of fingerlike projections, called the calyces, where urine is first deposited when it leaves the nephron units of the renal cortex (Figure 40-2).

The bilateral ureters are tubular organs approximately 10 inches (25 cm) long; with the aid of peristaltic waves generated by the ureter’s muscle layer, the bilateral ureters move the urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. The urinary bladder is a hollow organ lined with smooth muscle that overlaps in rugae formation, which enables the bladder to expand as it fills. When the bladder is full, sphincters open and urine flows into the urethra. The urethra is lined with a mucous membrane, and in males it functions both as the urinary canal and as a passageway for cells and secretions from various reproductive organs. The male urethra is about 8 inches (20 cm) long and is divided into three sections: the prostatic urethra (which passes through the prostate gland at the base of the bladder), the membranous urethra, and the penile urethra. In a female, the urethra is about 1 to 1½ inches (3 to 4 cm) long. Its proximity to the vagina and anus exposes the renal system to microorganisms that can cause infection. The urethra passes the urine from the bladder to the urinary meatus and outside the body. The process of urination is known as voiding or micturition.

Disorders of the Urinary System

The urinary tract is made up of a continuous mucosal lining that gives organisms entering the urethra a direct pathway through the system. Of the wide range of symptoms that occur in patients with disorders of the renal system, the most common involve changes in the frequency of urination. Dysuria, urgency, retention, and incontinence all are common symptoms. Abnormal functions of any part of the urinary tract often can be determined through urinalysis, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels, and analysis of creatinine clearance. (Urinalysis is discussed in Chapter 52.) Radiologic and endoscopic studies also are important in detecting urinary tract diseases. Table 40-1 summarizes common diagnostic tests of the urinary system.

TABLE 40-1

Common Diagnostic Tests of the Urinary System

| TEST | DESCRIPTION | PATIENT PREPARATION |

| Kidney-ureter-bladder (KUB) x-ray | Flat plate films of the abdomen; show the size, shape, location, and any malformations of the kidneys and bladder; used to visualize calculi. | No specific patient preparation; contraindicated in pregnancy. |

| Renal scanning | Nuclear scans to determine the size, shape, and function of the kidney or to diagnose obstruction or hypertension; radioisotope is administered intravenously, and images are taken to show distribution. | Patient should void before the procedure; no sedation or fasting required; patient drinks two or three glasses of water before scanning; contraindicated in pregnancy. |

| Cystography and voiding | X-ray evaluation with contrast dye to study bladder structure or function. | Clear liquids for breakfast; Foley catheter cystourethrogram inserted; may take x-ray films while patient is voiding (voiding cystourethrogram); after procedure, patient forces fluids to eliminate dye and prevent infection. |

| Intravenous pyelography (IVP); may be called intravenous urography (IUG) | Intravenous injection of dye, then x-ray films taken at intervals to show passage through kidneys and ureters into bladder; used to diagnose tumors, calculi, obstructions, and congenital renal problems. | Contraindicated in pregnancy and with iodine allergies; laxative evening before; liquid diet 8 hours before; adequate fluids after; may have enema morning of the study. |

| Arteriography (angiography) | Injection of dye into the renal artery. Computerized fluoroscopy permits visualization of the blood flow of the kidneys, and serial x-ray films are taken. Used to diagnose stenosis of the renal artery and highly vascular renal cancers. | Nothing by mouth (NPO) 2 to 8 hours before procedure; administer preprocedural medications as ordered; void before the study; warm flush may occur when dye is injected; check for allergies to iodine and shellfish. |

| Renal computed tomography (CT) | Can be done with or without contrast dye; transverse views of the kidney are taken by CT to detect tumors, abscesses, cysts, and hydronephrosis. | If contrast medium is used, fast 4 hours before procedure; scanner may make loud clicking sounds as it rotates; dye may cause flushing, metallic taste, and headache; check for allergies to iodine and shellfish; remove all metal objects. |

| Renal ultrasonography | High-frequency sound waves are transmitted through the kidneys to detect abnormalities; used to determine kidney size and to diagnose hydronephrosis, polycystic kidneys, and obstructions of ureters and bladder. | No food or fluid restrictions; noninvasive and painless. |

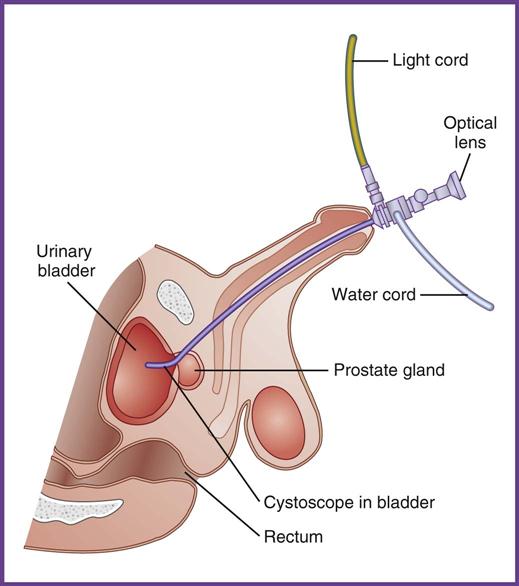

| Cystoscopy | Endoscopic view of urethra and bladder for biopsy; used to measure bladder capacity, to find or remove calculi, for dilation of urethra and ureters, and for placement of ureteral stents. | Enemas to clear bowel; force fluids before procedure if local anesthesia is used; for general anesthesia, NPO after midnight; preprocedural sedative to reduce bladder spasms; aftercare: monitor urinary output for 24 hours. |

| Retrograde pyelography | Injection of dye into the bladder, ureters, and kidneys through a cystoscope to detect stones and other obstructions; can replace an IVP for patients with renal failure, obstructions, or allergies to IV dye. | Same as cystoscopy; check for iodine and shellfish allergies. |

Urinary Incontinence

Urinary incontinence, which is a temporary or chronic loss of urinary control, can be the result of many conditions, including urinary tract infections, brain disorders, and tissue damage. This disorder also can be caused by straining or coughing in postsurgical patients and in patients with weak pelvic musculature; in such situations, the condition is called stress incontinence.

The treatment of incontinence depends on the causative factor. Behavioral approaches include bladder or habit training that teaches the patient to urinate according to an established schedule rather than when he or she has the urge to void. This is helpful for patients who are incontinent as a result of strokes, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, central nervous system lesions, or cystitis. Pelvic muscle exercises (Kegel exercises) that strengthen the muscles of the pelvic floor are helpful for patients with stress incontinence. Patients are trained to simulate stopping the flow of urine and holding that contraction for 10 seconds, in sets of 20, three times a day.

Patients with neurogenic bladder, who have lost control of urination because of central nervous system trauma or disease, may have to be catheterized to remove urine from the bladder. Intermittent catheterization to empty the bladder is preferable to indwelling catheters, which often lead to infection. External (condom) catheters can be used for male patients, but they are associated with an increased incidence of urinary tract infections (UTIs). If possible, the patient should be taught to perform routine catheterization throughout the day, or a family member may be involved in care.

Chronic incontinence can be treated pharmacologically with antispasmodic preparations, including tolterodine (Detrol), oxybutynin chloride (Ditropan), solifenacin (Vesicare), or darifenacin (Enablex). When all other treatments have failed, surgical intervention may be the answer. Several different suburethral sling procedures have proved successful in treating female incontinence. The surgeon uses a piece of abdominal tissue or a strip of synthetic material to compress the urethra so that urine does not leak during a stressful event, such as jumping or coughing. An artificial urinary sphincter is helpful for men with incontinence. A device shaped like a doughnut is implanted around the neck of the bladder; it keeps the urinary sphincter closed until the patient presses a valve implanted under the skin. This deflates the ring and releases urine from the bladder.

Urinary Tract Infections and Inflammations

UTIs occur frequently because the urinary system has a direct opening to the outside, and urine is an excellent medium for bacterial growth. Most UTIs are ascending, that is, they start with pathogen exposure in the perineal area, infecting the continuous mucosa of the urinary system, which in turn allows the pathogen to travel up through the urethra, bladder, and ureters to the kidneys. Infection and inflammation of the urethra is called urethritis and that of the bladder is cystitis. The resident flora of the colon, Escherichia coli, is the usual causative agent.

Women are more susceptible than men to UTIs because of the female anatomy (i.e., a short urethra and the proximity of the anus) and as a result of irritation caused by tampon use, the ingredients of bubble bath formulas, and sexual activity. Older men with prostatic hyperplasia and resultant urinary retention also are at risk for frequent urinary tract infections.

Urethritis

Urethritis, or inflammation of the urethra, is more common in men. It typically is caused by chlamydia or gonorrhea bacteria. Symptoms include the discharge of pus, an itching sensation at the opening of the urethra, and burning on urination. Infectious urethritis can cause cystitis in women, so sexual partners also should be treated. Urinalysis may show hematuria as well as pyuria (pus in the urine).

Cystitis

Cystitis, an infection of the urinary bladder, causes inflammation of the bladder wall and urinary urgency. Symptoms include very mild to acute discomfort in the lower abdomen, urinary frequency, and painful urination (dysuria). The patient may have signs of a systemic infection, including fever, general malaise, and leukocytosis. A positive diagnostic urinalysis shows more than 100,000 bacteria per milliliter of urine, pyuria, and hematuria. An infection of the urinary bladder is especially difficult to eliminate because of the bladder’s overlapping rugae walls. It is very important that patients understand that, to prevent a recurrence of the infection, they must complete the entire antibiotic prescription to destroy all the bacteria in the folds of tissue.

Pyelonephritis

Pyelonephritis, an inflammation of the renal pelvis and kidney, is the most common type of renal disease. It is caused by bacteria that ascend from the lower urinary tract and is associated with conditions such as urinary retention or obstruction that promotes urinary stasis and the growth of bacteria. It frequently is preceded by urethritis and cystitis. With pyelonephritis, pus collects in the renal pelvis, and abscesses form. Symptoms include fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, and flank (lateral lumbar) pain. The patient reports foul-smelling, dark urine with frequency and urgency.

Diagnostic studies include urinalysis of a clean-catch urine sample. It reveals hematuria, pyuria, increased white and red blood cells, albuminuria, casts, and bacteria. Urine cultures usually are done to determine the causative agent.

Treatment of Urinary Tract Infections

UTIs are treated with antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin (Cipro), nitrofurantoin (Macrodantin, Furadantin), sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra), and levofloxacin (Levaquin). Patients may also be prescribed a urinary tract analgesic, such as phenazopyridine hydrochloride (Pyridium), which is rapidly excreted in the urine and has a topical analgesic effect that helps relieve pain, burning, urgency, and frequency. However, Pyridium gives the urine an orange to red color, which initially may be misinterpreted as hematuria. Patients diagnosed with UTIs are encouraged to force fluids to dilute the urine and flush the urinary tract. A follow-up urinalysis should be run to confirm the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in curing the infection. UTIs tend to recur unless the cause of the infection is removed.

The medical assistant should instruct the patient to finish the entire antibiotic prescription as ordered, to maintain proper hygiene, to empty the bladder completely when the urge to void arises, and, for female patients, to wipe the bottom from front to back to discourage the spread of E. coli from the anal area toward the urethral region. Cranberry juice may be recommended as a prophylactic measure, because it contains substances that discourage E. coli growth and help maintain the acidity of urine.

Glomerulonephritis

Acute glomerulonephritis, or degenerative inflammation of the glomeruli, usually develops in children and adolescents about 2 weeks after a streptococcal infection, such as strep throat or scarlet fever. Symptoms include low-grade fever, anorexia, general malaise, and flank pain. Hypertension and edema may occur because of reduced renal function. Urinalysis shows hematuria and proteinuria. Diuretics, such as triamterene and hydrochlorothiazide (Dyazide) or furosemide (Lasix), may be given to control hypertension and reduce edema. The prognosis usually is good; most patients recover spontaneously, but in some patients, the condition progresses to a chronic state.

Chronic glomerulonephritis may also be called nephritis or nephrotic syndrome. It typically develops over many years and may be associated with chronic diseases that affect the blood vessels, such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and diabetes mellitus. Chronic glomerulonephritis causes progressive, irreversible nephron damage that frequently results in renal failure. At first the patient is asymptomatic, but as the disease progresses and more glomerular damage occurs, the patient develops anorexia, fatigue, hypertension, hematuria, proteinuria, oliguria (scanty urination), and edema. The cause of chronic glomerulonephritis is unknown, but it may be associated with an antigen-antibody reaction in the glomerular capsule that ultimately destroys the nephron unit. Treatment is supportive and involves an attempt to control symptoms by administering antihypertensives and diuretics, as well as prescription of a diet low in protein with limited sodium and potassium to slow the progression of the disease. Glomerulonephritis is a leading cause of kidney failure; ultimately, many patients require kidney dialysis. The only cure for the disease is a kidney transplant.

Urinary Tract Disorders and Cancers

Renal Calculi

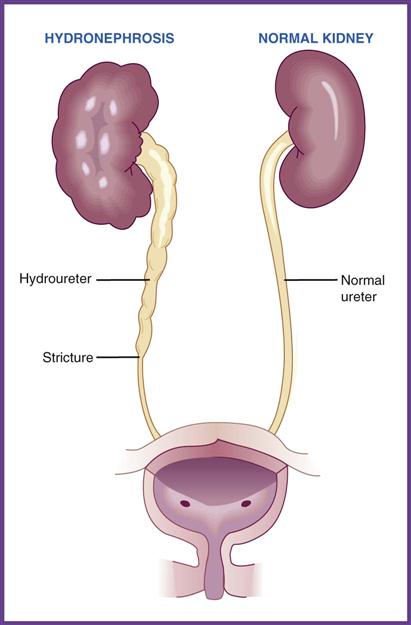

Renal calculi, or kidney stones, are created when crystals in the urine (e.g., calcium, oxalate, uric acid) collect in the kidney, or when fluid intake is low, creating a highly concentrated filtrate. The tendency to develop kidney stones runs in families, and patients with a history of renal calculi are at increased risk for developing more stones in the future. Small stones usually do not cause any difficulty until they grow large enough to lodge in the ureters or renal pelvis. If a stone blocks the flow of urine, infection can develop from the resultant stasis. This blockage also can result in hydronephrosis, a backup of urine that causes dilation of the ureters and calyces and increases pressure on the nephron units. Other signs and symptoms include hematuria; cloudy, foul-smelling urine; nausea and vomiting; a persistent urge to urinate; and fever and chills if an infection is present.

If stones are located in the kidney or bladder, the patient often is asymptomatic, and frequent infections are the only presenting problem. If the calculi begin to move or are lodged in the ureters, the patient experiences renal colic, which is severe pain in the flank region that fluctuates in intensity over periods of 5 to 15 minutes. As the calculi progress down the ureter, the pain radiates to the lower abdomen, groin, and genital areas on the affected side. If the stone stops moving, the pain stops until it starts to move again. This pattern continues until the stone is passed or it is treated medically. The patient may be able to pass small stones by drinking large amounts of fluid (2 to 3 quarts of water a day). However, larger stones or calculi that cause bleeding, kidney damage, or persistent infection require medical intervention.

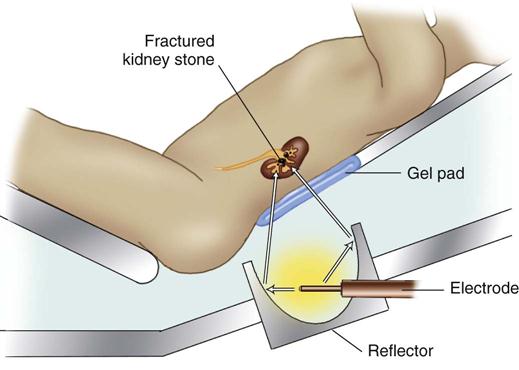

The physician may perform a cystoscopic examination to visualize the urethra and bladder and to remove any stones found (Figure 40-3). The most common procedure for treating calculi is extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL), which uses vibrations of powerful sound waves to break the stones into fragmented pieces that can be passed through the renal system. Diagnostic studies are performed to identify the exact location of the calculi, and x-rays or ultrasound is used during the procedure to keep track of the calculi and to monitor treatment progress. The patient may be immersed in water during the procedure or may lie on a water-filled cushion as high-energy sound waves are passed through the body toward the exact location of the calculi (Figure 40-4). The procedure causes moderate pain, so the patient usually is pre-sedated or is given a light anesthetic. The patient wears earphones during the treatment because of the loud noise created each time a shock wave is generated. Side effects of the treatment include flank tenderness, hematoma formation across the treatment site, and hematuria. Measures for preventing recurrence include drinking 3 to 4 quarts of fluid a day, preferably water, and following a diet that is low in sodium and animal protein.

Hydronephrosis

Hydronephrosis, or swelling of the kidney caused by inability of urine to drain from the renal pelvis, usually results from blockage caused by renal calculi, but it may also be caused by an enlarged prostate or a tumor. Hydronephrosis can occur bilaterally or unilaterally. The condition frequently is asymptomatic, or patients may complain of mild flank pain as the renal capsule is distended. Urine testing detects hematuria and, if infection develops from stagnant urine, pyuria. It is important to treat hydronephrosis aggressively, because continued pressure from blocked urine flow can cause tissue necrosis and ultimately can lead to irreversible kidney damage. Removing the blockage corrects the condition (Figure 40-5).

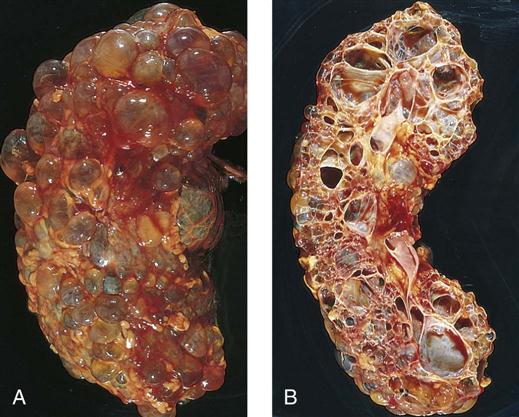

Polycystic Kidneys

Polycystic kidney disease typically is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder, which means that one parent has the disease and each child has a 50% chance of inheriting it. No indications of the disease occur in children, but as time goes on, normal renal tissue in both kidneys is replaced by multiple, benign, fluid-filled cysts (Figure 40-6). The nephrons and collecting tubules become dilated, fused, and infected. As the cysts enlarge, they compress the surrounding tissue, causing necrosis, uremia, and renal failure. Symptoms do not usually become apparent until the individual reaches adolescence or adulthood. Patients with polycystic disease have a family history of kidney disease or renal failure, flank pain, hematuria, and hypertension. They also are more likely to develop UTIs and renal calculi. Because cyst formation is progressive, these patients eventually require renal dialysis or kidney transplantation.

Bladder Cancer

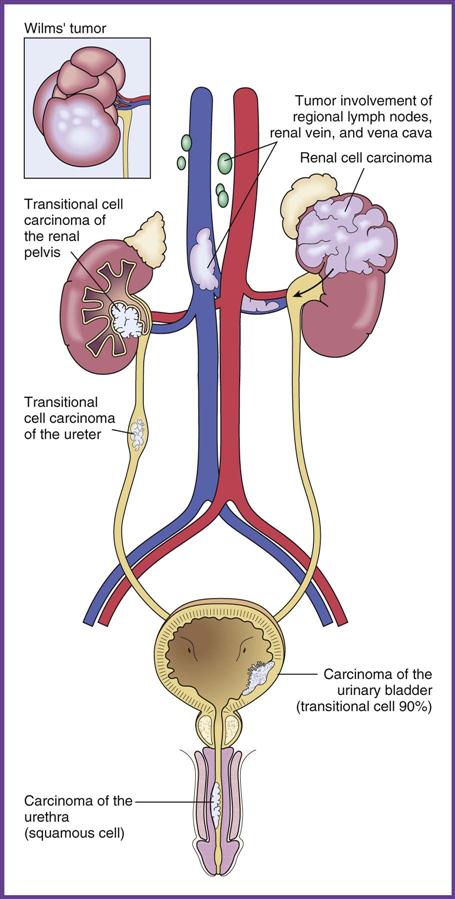

The most common cancer of the urinary tract affects the bladder (Figure 40-7) and is two to three times more common in men than in women. Bladder cancer is characterized by one or more tumors that can metastasize through the blood or surrounding pelvic lymph nodes. Because 50% to 90% of patients experience a recurrence of bladder tumors, follow-up testing that can identify recurrence is extremely important. NMP22 is a urine test that screens for recurrence of the disease. It identifies a protein in bladder cells that are either precancerous or cancerous. Ninety percent of bladder cancers are attributed to these particular cells, which are called transitional cells because they are cubelike when the bladder is empty and flat when it is full. The test can be performed in the physician’s office, and the results are available in 1 hour. If the NMP22 test result is positive, cystoscopy is performed to confirm the presence of abnormal cells.

Smoking is the greatest single risk factor for the development of bladder cancer. The carcinogens from tobacco become concentrated in the bladder and eventually cause cellular changes in the walls of the organ. Other risk factors include occupational exposure to chemical carcinogens (e.g., oil, rubber, dyes), drinking pesticide-contaminated water, treatment with certain anticancer drugs, and recurrent parasitic infections of the bladder. If the cancerous cells are confined to the inner lining of the bladder, a transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT) is performed. The physician passes a small wire loop through the urethra and uses an electrical current or a laser to burn away the cancer cells. The procedure may cause dysuria or hematuria for a few days. If the tumor has invaded the walls of the bladder, treatment may require a partial or complete cystectomy (removal of the bladder), chemotherapy, and the use of interferon to boost the patient’s immune system. The current treatment of choice is implantation of radioactive seeds in the bladder to destroy the affected tissue.

Renal Carcinoma

Adenocarcinoma of the kidney, or renal cell cancer, is a primary tumor that can be cured if it is diagnosed and treated in the early stages. However, affected patients frequently are asymptomatic, which gives the tumor the opportunity to metastasize to the lungs, liver, male urogenital system, bone, or brain before it is diagnosed. Renal cell carcinoma typically occurs in patients over age 50 and is seen more often in men and in smokers. Signs and symptoms of the disease include flank pain, anorexia, anemia, hematuria, and an increased white blood cell count. Surgical nephrectomy is the treatment of choice. Although the prognosis for patients with the tumor has improved, the 5-year survival rate is still only approximately 40%.

Wilms’ Tumor

Wilms’ tumor, or nephroblastoma, is cancer of the kidney in children. Although the condition appears to be caused by a genetic defect, very few of the children diagnosed with Wilms’ tumor have a family history of the disease. It usually occurs unilaterally, is diagnosed most frequently at age 3, and rarely occurs after age 8. The tumor may be noticed by parents as a mass in the child’s abdomen or by a physician during a routine physical examination. The preferred treatment is a partial or complete nephrectomy combined with chemotherapy. The survival rate for children diagnosed and treated for Wilms’ tumor is greater than 90%.

Renal Failure

Acute renal failure has a sudden, severe onset caused by exposure to toxic chemicals; circulatory collapse from serious burns or heart disease; acute bilateral kidney infection or inflammation; occlusion of the renal arteries; or complications from surgery. Blood tests show high BUN and creatinine levels, and the patient experiences acute onset of oliguria. The primary problem must be resolved as quickly as possible to prevent necrosis and permanent kidney failure.

Chronic renal failure is a slowly progressive process caused by gradual destruction of the kidneys’ ability to filter waste materials. Diabetes mellitus is the leading cause of chronic renal failure in the United States, but it also may be caused by hypertension, glomerulonephritis, polycystic kidneys, long-term hydronephrosis resulting from urinary obstruction, lead poisoning, or renal artery stenosis. Symptoms of the condition may not be evident until as much as 75% of the kidney is no longer functioning.

Patients with chronic renal failure pass through several stages, starting with an early stage of decreased reserve in which no clinical signs are apparent but serum creatinine levels are consistently higher than average. The middle stage of renal insufficiency is marked by hypertension, elevated BUN and creatinine levels, and a low urine specific gravity. End-stage renal failure (uremia) is marked by oliguria that progresses to anuria (no urine output), edema, hypertension, acidosis, and azotemia. The end result is that the kidneys can no longer remove waste products from the blood, and toxicity develops. To survive, the patient must be placed on dialysis or receive a kidney transplant.

Treatment

Dialysis, or cleansing of the blood, is used to treat acute renal failure until the problem is reversed, or, for patients in end-stage renal disease, until they receive a transplant. The two forms of dialysis are hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Hemodialysis usually is done in an outpatient clinic or hospital. The process uses a machine known as an artificial kidney, or dialyzer, to filter waste products from the blood and return the cleansed blood to the body (Figure 40-8). A surgically placed cannula or shunt creates an internal fistula between an artery and a vein. During the procedure, approximately 1 cup of blood at a time passes from the shunt through a tube to the semipermeable membrane of the dialysis machine. The membrane filters the waste out of the blood, which then is returned to the patient’s vein. Patients on hemodialysis require anticoagulant therapy to prevent clots from forming during the blood transfer process. Hemodialysis usually is needed three times a week; the procedure takes approximately 3 to 4 hours each time.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree