Assisting in Pediatrics

Learning Objectives

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary.

2. Apply critical thinking skills in performing the patient assessment and patient care.

3. Describe childhood growth patterns.

4. Summarize the important features of the Denver II Developmental Screening Test.

5. Identify four different growth and development theories.

6. Explain common pediatric gastrointestinal disorders and their signs, symptoms, and treatment.

7. Classify disorders of the respiratory system in children.

8. Distinguish among pediatric infectious diseases.

11. Demonstrate how to document immunizations and maintain accurate immunization records.

12. Compare and contrast a well-child and a sick-child examination.

13. Outline the medical assistant’s role in a pediatric examination.

14. Measure the circumference of an infant’s head.

15. Obtain accurate length and weight measurements and plot pediatric growth patterns.

16. Accurately measure pediatric vital signs and perform vision screening.

17. Correctly apply a pediatric urine collection device.

18. Describe the characteristics and needs of the adolescent patient.

19. Specify child safety guidelines for injury prevention and management of suspected child abuse.

20. Summarize patient education guidelines for pediatric patients.

21. Discuss the legal and ethical implications in a pediatric practice.

Vocabulary

anomaly A congenital malformation that occurs during fetal development.

attenuated (uh-ten-yuh-wat′-ed) Weakened or changed; refers to the virulence of a pathogenic microorganism.

hydrocephaly (hi-dro-suh′-fuh-le) Enlargement of the cranium caused by abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid within the cerebral system.

laryngoscopy (lar-uhn-gahs′-kuh-pe) Visual examination of the voice box area through an endoscope equipped with a light and mirrors for illumination.

microcephaly Small size of the head in relation to the rest of the body.

serous A thin, watery, serumlike drainage.

stridor A shrill, harsh respiratory sound heard during inhalation when a laryngeal obstruction is present.

suppurative Characterized by the formation and/or discharge of pus.

Scenario

Susie Kwong, CMA (AAMA), who has 2 years of experience, has accepted a new position with North Hills Pediatrics, a large multiphysician practice. Susie’s primary responsibility will be to assist in the clinical area, but she also will have to rotate through the message screening center in the office. Office policy states that telephone screening employees should manage problems as much as possible, but if patient callbacks are needed, they are to be referred to the physician on call that day by noon for morning calls and no later than 5 PM for afternoon calls. Although the physicians in the practice have developed specific guidelines for managing patient problems, Susie is anxious about this responsibility, so she asks to work with the screening staff for several days before she starts answering incoming calls.

While studying this chapter, think about the following questions:

• What other clinical responsibilities should Susie be prepared to perform?

• How can Susie maintain her skill level and continue to learn about patient-centered pediatric care?

Pediatrics is the medical specialty that deals with the development and care of children and with the treatment of childhood diseases. Pediatric patients range in age from newborn to puberty. Some practices continue to see the child until he or she graduates from high school. Subspecialties within pediatrics include surgery, cardiology, and psychiatry.

Approximately 50% of the patients in a pediatric office are there for well-baby or well-child visits. The roles of the pediatrician and the medical office staff are to supervise and help maintain the health of these patients. Parents must be involved in the care and development of their young children for treatment to be a success. The medical assistant can help by encouraging therapeutic communication among the patient, parents, and medical staff. The trust a child develops in the relationships and consideration received in the physician’s office forms the basis of good medical care.

Pediatric care actually starts before the child is born, with promotion of good general health for mothers before conception and during pregnancy. The confidence and enthusiasm of parents can have a significant impact on an infant’s physical and emotional well-being.

Normal Growth and Development

The terms growth and development often are used together. They refer to the combination of changes a child goes through as he or she matures. Growth refers to measurable changes, such as height and weight. The first determinant of these physical characteristics is the genetics inherited from the parents; however, a child’s growth can be influenced by many factors, including nutritional status, environmental factors, and the presence of disease. Development considers qualitative maturation in motor, mental, social, and language skills. A child’s development is determined by a combination of prenatal, environmental, and caregiver factors. Each child has his or her own pattern of growth and development. Pediatric assessments are individualized for each child according to age, developmental level, health condition, family characteristics, and past experiences with healthcare professionals. The pediatrician checks for indications of irregularities in growth and development by comparing a child’s physical, intellectual, and social levels with published national standards. This comparison indicates whether the child is at the appropriate stage of growth and development for his or her chronologic age.

Growth Patterns

Physical growth is one of the most visible changes in childhood. The average birth weight is 7 to 7½ pounds, and in 6 months, the baby’s birth weight doubles. Growth then slows slightly; by 1 year of age, the birth weight has tripled and length has increased by 50%. By age 2, the child has reached approximately 50% of his or her adult height. Between ages 1 and 2, the child gains approximately ½ pound per month. Between ages 2 and 3, weight gain averages 3 to 5 pounds and height increases 2 to 2½ inches. Most children slim down during this period, so that by the time the third birthday arrives, the potbellied toddler has become the characteristic preschooler.

During the preschool period, ages 3 to 6 years, weight increases 3 to 5 pounds per year; height increases at a slower but steady rate of 1½ to 2½ inches per year. By age 4, the child usually has doubled the birth length. During this time, the legs are the fastest growing part; fatty connective tissue continues to increase slowly until approximately age 7. This same growth rate continues through the school-aged period, 6 to 12 years, and as this period of development ends, the child usually is into a growth spurt that indicates impending puberty.

The growth spurt continues for approximately 2 years, and the child then reaches adolescence (ages 12 to 18 years). During this period, the adolescent gains almost half of his or her adult weight, and the skeleton and organs double in size. Weight increases in girls by 20 to 25 pounds and in boys by 15 to 20 pounds. Girls grow 5 to 6 inches, and boys grow 4 to 5 inches. As the growth spurt is completed, the teenager reaches sexual maturity. In girls, sexual maturity is signaled by the onset of the menstrual cycle; in boys, it is determined by the presence of sperm in the semen. The timing of sexual maturity in both genders varies greatly.

Skeletal growth is complete in girls between 15 and 16 years of age and in boys between ages 17 and 18. Skeletal growth is considered complete when the growth plates (epiphyseal plates) of the long bones of the extremities have fused completely.

Growth charts that can be used to compare the child’s individual growth pattern with national standards have been used since 1977, but in 2000 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revised the charts to reflect cultural and racial diversity (samples are available at www.cdc.gov/growthcharts). The CDC charts take into account whether an infant was formula fed or breast-fed, because breast-fed infants may grow differently during the first year of life.

In addition, the CDC growth charts include information on the average body mass index (BMI) for infants and young adults 2 to 20 years of age, giving pediatricians another weapon in the fight against childhood obesity. As was discussed in Chapter 30, the BMI is a means of assessing the relationship between height and weight. BMI conversion charts typically are available, but the BMI can be calculated by dividing the child’s weight in kilograms by the height in meters squared, or

Denver II Developmental Screening Test

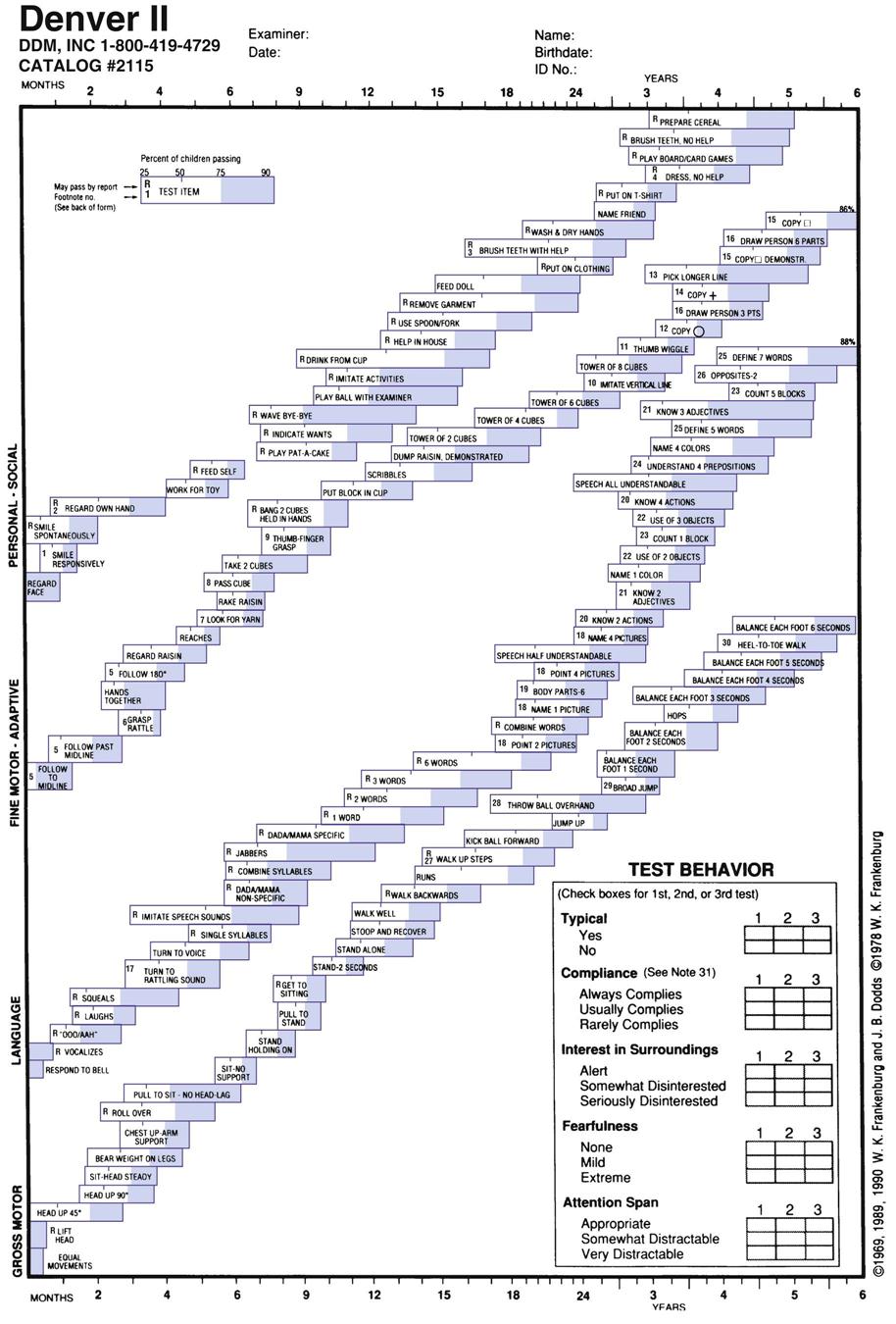

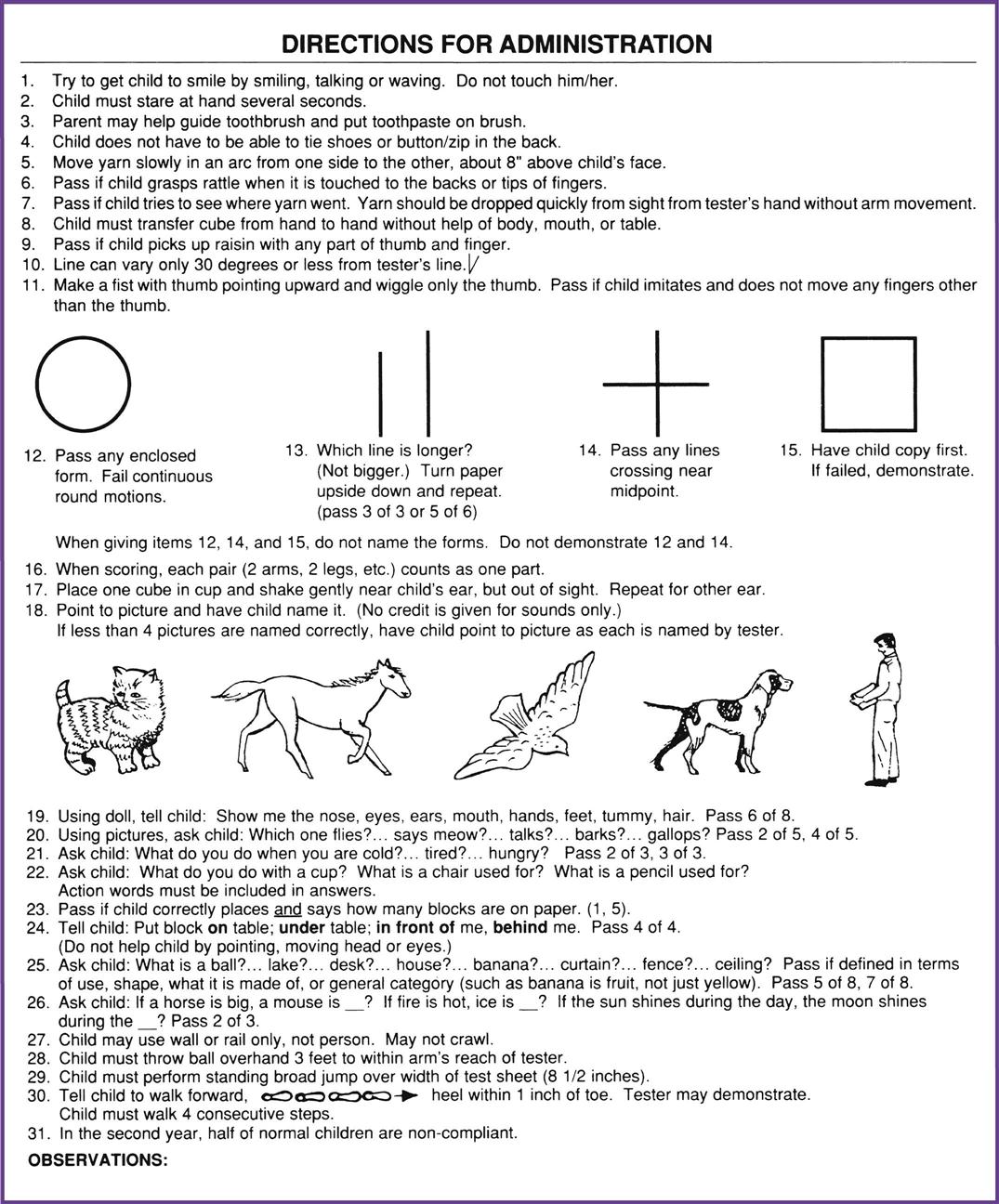

Each child develops individually and attains developmental plateaus differently. The Denver II Developmental Screening Test is a standardized tool used to screen for developmental delays, to investigate concerns about an infant’s development, or to monitor high-risk children for potential problems (Figures 42-1 and 42-2). The test should be given at ages 3 to 4 months, 10 months, and 3 years. Although it is not difficult to administer, only those trained in the procedure and interpretation of results should give it. The assessment focuses on four developmental areas:

The results of the test are analyzed and determined to be normal or suspect, or the child is diagnosed as untestable. With an abnormal finding, the child should be rescreened in 1 to 2 weeks to rule out temporary developmental delays caused by fatigue or anxiety. If those results are abnormal, the child may be retested with other developmental tests, either by the pediatrician or by a professional pediatric testing agency.

Developmental Patterns

General patterns of child development occur rapidly during the first year of life as the infant progresses from reflex activities (e.g., grasping fingers and sucking) to learning to manipulate simple objects (e.g., pulling open drawers or throwing toys out of the crib). In addition to these motor skills, the child learns verbal patterns, progressing from cooing and crying for attention to speaking his or her first words.

By age 3, the child is showing increased autonomy. Now the child can walk, is toilet trained, sits at the table and eats with the family, can make simple sentences, understands the word “no,” and even imitates the parent by using verbal gestures that he or she has seen used. The child’s vocabulary consists of up to 900 words.

During the preschool stage the child becomes increasingly independent and initiates activities. Preschoolers have mastered many gross motor skills and are perfecting their fine motor development. Verbal communication has increased to full simple and even complex sentences but remains quite literal. For example, if you tell a preschool child that you are going to fly to visit Aunt Sue, the child thinks you are going to flap your arms and fly. Nonverbal communication skills are also being mastered. The vocabulary now includes more than 2,000 words. During this period, children need to develop social skills, such as sharing and taking part in peer group activities.

The school-aged child has perfected fine motor skills and can paint, draw, and play an instrument, enjoys team activities, and expands reading and writing skills. His or her intellectual skills are developing, and social skills are going through refinement as a sense of self-achievement and self-worth is developed. During this time the child learns and tests the rules for socializing outside the immediate family as an independent individual.

Adolescence, or the transition stage, is the time when the individual attempts to establish an adult identity. The teenager proceeds by trial and error, experimenting with adult roles and behavior patterns. Traditional values learned in childhood may be questioned, and peer relationships take on new importance. During this time teenagers must develop the emotional maturity and motivation to make reasonable decisions. The teen looks to family members for encouragement and guidance in making decisions that will help develop self-confidence and to become patient and less impulsive and self-centered.

Developmental Theories

Psychologists have been researching and developing theories about human behavior since the beginning of the twentieth century. The first of these theorists to gain influence was Sigmund Freud, who believed that the motivating stimulus for human behavior is the libido, which is defined as an individual’s pleasure-seeking instincts. Freud’s theory describes four major components of the mind: the unconscious mind, which cannot be accessed but affects our behavior; the id, which focuses on immediate self-gratification; the ego, which develops throughout life and balances the immediate desires of the id with the reality of the social world; and the superego, the individual’s conscience, which helps the child incorporate social expectations and norms. Freud also was the first therapist to identify developmental stages that all individuals must achieve, including the oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital stages.

The next developmental theory to gain general acceptance was the psychosocial approach of Erik Erikson. Erikson expanded Freud’s work to recognize cultural and social influences on individual development. His theory is based on eight stages of development that the individual must pass through and master. Each stage focuses on a developmental crisis, starting in infancy and ending in old age. According to Erikson, the stages that children must master include:

Jean Piaget’s developmental theory focuses on intellectual growth, with four stages of cognitive development. From birth to 24 months, children progress through the sensorimotor stage, which starts with reflexive behavior and advances to learning by doing. The preoperational stage (2 to 7 years) is characterized by language development and using play to understand the world. In the concrete operational stage (7 to 11 years), children develop logical thinking and become less egocentric. Finally, the formal operational stage (11 years or older) brings abstract thinking and deductive reasoning to establish values and determine the meaning of life.

Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory, which focuses on moral reasoning, involves levels similar to Piaget’s cognitive development theory, yet recognizes the influence of culture and interpersonal relationships on the child’s moral development. In preconventional morality, the child’s behavior is based on the external control of authority figures. The child perceives the goodness or badness of a behavior based on parental reaction. In the conventional level, the child wants to follow the rules of the group or society and internalizes the values of others. As the child reaches adolescence, the postconventional level, he or she develops individual morality and values, and behavior is regulated internally rather than externally. Table 42-1 summarizes these growth and development theories.

TABLE 42-1

Summary of Growth and Development Theories

| AGE GROUP | FREUD (1856-1939) PSYCHOSEXUAL THEORY | PIAGET (1896-1980) COGNITIVE THEORY | ERIKSON (1902-1994) PSYCHOSOCIAL THEORY | KOHLBERG (1927-1987) MORAL REASONING |

| Infant | Oral stage; child operates with the pleasure principle, and the id develops. | Sensorimotor level; uses reflexive behavior; has to do things to learn. | Building basic trust versus mistrust; learning drive and hope. | Avoids punishment and obeys for obedience’s sake. |

| Toddler | Passes through oral aggressive stage to anal stage; elimination is used to control and inhibit. | Coordinates more than one thought at a time; uses thought to create new solutions. | Autonomy versus shame and doubt; learning self-control and willpower. | Avoids punishment and the power of authority figures. |

| Preschool to early school years | From phallic stage, in which the ego (conscious reality) develops, to latent stage, in which superego (morality) develops. | Intuitive-preoperational; preschoolers are egocentric and have magical thinking. Early school-aged children begin to develop understanding of cause and effect. Child functions symbolically using language; develops understanding of life events and relationships. | Preschool processing initiative versus guilt and attempting to develop direction and purpose. Children mimic others and are more purposeful in establishing goals. | Develops preconventional morality; follows the standards of others to avoid punishment or to earn a reward; recognizes some things are self-satisfying and some are done to satisfy others. |

| School age | Latent stage continues; superego develops morality or a conscience; represses the sexual drive. | Concrete operations: uses mental reasoning to solve problems; attempts to reach logical solutions; tests beliefs to establish values. | Industry versus inferiority; establishing methods for solving problems and a feeling of competence; mastering tasks and using hands to create things. | Conventional morality; doing what is expected is important. Children need to be good in their own eyes as well as doing what they perceive others expect of them; they want to please others. |

| Adolescence | Genital stage | Formal operations developing; adolescents are determining values that will guide their lives and religious affiliations; they develop abstract ideas that can be based in reality. | Identity versus role confusion; developing self-identity that will determine devotion and fidelity in future relationships. | Postconventional morality; developing a respect for the laws of society; adolescents are learning to consider the greatest good for the greatest number; values are related to one’s group. Behavior is controlled internally. |

Pediatric Diseases and Disorders

The disease process in pediatric patients poses special problems, because children are constantly changing both physically and functionally. As a child grows and develops, the immune system matures, and with the aid of routine prophylactic immunizations, the child acquires long-term protection against certain infectious diseases.

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Colic

Colic usually is seen in the newborn period or in early infancy. The problem is intermittent. The classic situation is an infant between 2 weeks and 4 months of age who has crying episodes that occur at least three times a week for longer than 3 hours a day and lasting 3 weeks. During an attack, the infant draws up the legs, clenches the fists, and cries inconsolably. The abdominal distress of colic usually occurs in the late afternoon and evening. Many theories have been suggested for why infants have colic, but none has been proven correct. If the baby is fed infant formula, pediatricians recommend switching formulas, perhaps to a non–cow’s milk type, because this may help relieve the infant’s discomfort. Treatment consists of determining the cause; however, the child frequently outgrows the condition before the causative agent can be identified. Drugs are not helpful and in some cases may be dangerous for the infant. Parents need reassurance that they are not responsible for the child’s discomfort, and they may find counseling and assistance in developing coping techniques helpful.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea can be caused by a variety of microorganisms, including bacteria, viruses, and parasites. However, children sometimes can have diarrhea without having an infection, such as when diarrhea is caused by food allergies or by certain medications, such as antibiotics. Diarrhea is diagnosed when the child has two or more watery or apparently abnormal stools within 24 hours. The child may not show other signs of illness or may have nausea, vomiting, stomach aches, headache, or fever. If the diarrhea continues for longer than 2 days, medical intervention is needed, because prolonged diarrhea, in which fluid loss becomes excessive, can cause dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. In addition, a resultant diaper rash and excoriation can make defecating painful.

Pediatric diarrhea needs to be followed closely with observation and, in the case of bloody stools, laboratory analysis to determine the causative factors. Infants and small children should be followed up by telephone in 12 hours and then daily until the diarrhea has stopped. Parents should know the indications of dehydration, including lack of tears when crying, lethargy, fewer wet diapers or decreased urination, dry mouth and lips, and weight loss. The physician may recommend the use of oral rehydration therapy, such as Pedialyte or Infalyte; small amounts (approximately 2 tablespoons) are offered at a time (i.e., every 15 minutes) to prevent vomiting. Soft drinks, juices, sport drinks, and tea should be avoided, because they lack electrolytes and may lead to even more diarrhea. Parents should be informed that the child’s diarrhea may not stop when the child is given oral rehydration therapy, but the fluids prevent the child from becoming dehydrated. It is important to continue to feed the child, because lack of food can cause damage to the villi in the small intestine. If breast-fed, the baby should continue to nurse, and formula feeding also should be continued.

For older children, a diet of bananas, rice, applesauce, and toast (the BRAT diet) or foods high in carbohydrate are most helpful in enhancing fluid and sodium absorption in the child’s irritated gastrointestinal tract. The child should not be given over-the-counter (OTC) antidiarrheal medications, such as Pepto-Bismol, Kaopectate, Imodium, or Lomotil, because these can cause serious side effects, including decreased motility of the bowel, respiratory depression, and drowsiness. The physician may prescribe antibiotics if stool cultures test positive for pathogens. Children with severe dehydration require hospitalization with intravenous (IV) hydration to replace electrolytes and fluids.

Failure to Thrive

Failure to thrive is a symptom more than a disease. It is diagnosed in an infant or young child whose weight is consistently below the 3rd percentile on standardized growth charts or one who is 20% below the ideal body weight for length. Physical, mental, and social skills also are delayed in these children. Manifestations include failure to roll over, smile, coo, stand, or walk at age-appropriate developmental levels. Failure to thrive can be caused by a physiologic factor (e.g., malabsorption disease or cleft palate), or it may be related to a problem with the parent-child relationship. The physician needs an accurately recorded history of the child’s birth weight and subsequent length, weight, and head circumference measurements. A comprehensive family history is important to rule out genetic growth abnormalities or a history of malabsorption problems, such as cystic fibrosis or celiac disease.

Children with failure to thrive need more calories than usual—approximately 150% of their normal calorie load—to catch up to their target weight. Both medical and social factors are evaluated in the treatment of children with this problem. Experts believe that infants may suffer from this problem if they are being neglected; however, low weight gains also are possible with extremely attentive and cautious parents. The family must be considered as a whole to treat nonorganic causes effectively. Treatment may include the use of support groups and parental counseling.

Obesity

Just as with adult weight patterns, children are assessed according to their BMI. A child’s level of body fat varies as the child grows; for example, children normally slim down as they reach school age, and very often their weight increases as they mature from adolescence to adulthood. In addition, body fat levels vary between boys and girls as they reach puberty. Pediatricians therefore use growth charts that plot the child’s BMI-for-age to determine whether the child’s weight, in comparison with height, is within healthy limits. A child is considered overweight if the BMI-for-age is between the 85th and 94th percentiles; the child is identified as obese if the BMI is at or greater than the 95th percentile. It is estimated that more than 30% of school-aged children are overweight, and almost 16% are considered obese.

The reasons for childhood obesity vary; they include a family history of obesity, inactivity, high-calorie diets, and stress. In rare cases, childhood obesity may be caused by metabolic or endocrine disorders. Overweight and obese children are at greater risk of developing serious health conditions, including asthma, diabetes mellitus type 2, sleep apnea, and hypercholesterolemia, which increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and hypertension. The psychosocial impact of obesity can be overwhelming for many children, because isolation, loneliness, and lack of self-esteem are common. Studies have shown that 70% to 80% of overweight teenagers become overweight adults, with all the health risks and psychological issues that come with weight problems. The pediatrician can provide assistance by recommending a comprehensive diet and exercise program that emphasizes healthy living. The medical assistant can help by providing educational materials, encouragement for the child and parents, and referral to community education and support programs.

Respiratory Disorders

Common Cold

The common cold, or infectious rhinitis, has more than 100 causative pathogens and is highly contagious. It is spread through respiratory droplets from rhinitis, sneezing, or coughing, either from direct contact or from touching contaminated items. The signs include nasal congestion, low-grade fever, and general malaise. Most colds are self-limiting and run their course in about a week. In infants and young children, the primary concerns are nasal congestion and loss of appetite. The parent may need to be shown how to use a nasal bulb syringe to suction the nose of an infant (Figure 42-3). Secondary infections in the lower respiratory tract or in the middle ear can occur.

One of the secondary infections that can occur is strep throat, which is caused by group A Streptococcus bacteria. It is easily spread when an infected person coughs or sneezes contaminated droplets into the air and another person inhales them. A person also can become infected by touching such secretions and then touching the mouth or nose. Symptoms of strep throat infections may include severe sore throat, fever, headache, and lymphadenopathy; also, the throat appears bright red, and pustules may be present on the tonsils. If they are not treated with antibiotics, strep infections can lead to scarlet or rheumatic fever; infections of the skin, bloodstream, or ears; and pneumonia. Scarlet fever is characterized by a bright red, rough-textured rash that spreads over the child’s body. Rheumatic fever is a serious disease that can damage the heart valves.

Otitis Media

Infection or inflammation of the middle ear usually is a side effect of a cold or other upper respiratory tract disorder, but it also can be caused by allergies. Otitis media usually occurs in children younger than 3 years of age. Signs include inflammation of the middle ear, with fluid building up behind the tympanic membrane. The child may cry persistently, tug at the ear, have a fever, be irritable, and have diminished hearing in the affected ear. These symptoms sometimes may be accompanied by diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting.

Otitis media is classified as either serous (Figure 42-4) or suppurative (Figure 42-5), depending on the composition of the accumulated fluid in the middle ear. Because the condition may be caused by bacteria or a virus, determining the most appropriate treatment can be difficult. Traditionally, children with indications of a middle ear infection were treated with antibiotics; however, if the infection is caused by a virus, antibiotics do not help. Because of concern over the growing problem of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria, current recommendations call for treatment with acetaminophen or ibuprofen if the child is in pain or has a fever, but the use of antibiotics is delayed for 48 to 72 hours to give the body a chance to fight the infection by itself. Children 6 to 24 months old who show no improvement in symptoms within 24 hours and children older than 24 months who do not improve within 72 hours should be prescribed antibiotics (typically amoxicillin or azithromycin [Zithromax]). The medication usually is ordered for a shorter course (i.e., 5 days rather than 10 to 14 days), because patients and their parents comply better with short-term treatment. Regardless of the length of treatment, it is very important that the complete prescription be administered to prevent a relapse.

If fluid in the middle ear persists for longer than 3 months and/or if the child experiences hearing loss, the physician may recommend a myringotomy; in this operation, a small incision is made in the tympanic membrane and a tube is inserted to drain the fluid and balance the pressure between the outer and middle ear. The tube typically stays in the eardrum for 6 to 12 months and falls out as the child grows. While tubes are in place, it is important to keep water out of the child’s ears and to report any drainage to the physician.

Croup

Croup is a viral inflammation of the larynx and the trachea that causes edema and spasm of the vocal cords. This varying degree of obstruction of the cords produces hoarseness, a harsh barking cough, and stridor during inhalation. The episodes usually occur at night, and symptoms ease by morning. The infection usually is self-limiting, and the child typically recovers without treatment. Mild croup can be relieved by using a cool mist humidifier in the child’s room, sitting with the child in a steamy bathroom, or even taking the child outside if the air is cool. Children with allergies may require medical treatment. If the problem becomes chronic or continues for a period of time, the child may need to be treated with corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone). The physician may recommend laryngoscopy to visualize the vocal cords or may order throat cultures to determine the underlying cause of the inflammation.

Bronchiolitis

Bronchiolitis is a viral infection of the small bronchi and bronchioles that usually affects children younger than 3 years of age. The infection varies in severity and is seen in children with a family history of asthma and children exposed to cigarette smoke. The child typically has a previous history of rhinitis and cough with an acute onset of wheezing and dyspnea. Symptoms occur because of inflammation, edema, increased secretions, and bronchospasm in the respiratory pathway. Treatment includes acetaminophen for discomfort and fever and a bronchodilator inhaler (albuterol sulfate [Proventil]) or nebulizer treatment for relief of wheezing. Most children fully recover in 2 weeks, but as many as 50% have recurrent wheezing and coughing.

Asthma

Asthma is the most common chronic health problem among children. It is the result of two specific reactions, bronchospasm and inflammation. During an asthma attack, the bronchial tubes begin to spasm, which reduces the amount of air that can pass through them. At the same time, the tissue lining the bronchioles becomes edematous and secretes mucus; therefore, in an asthma attack, the smaller airways are filling up with mucus and secretions. Air passing through these secretions causes the classic symptom of asthma—wheezing on expiration. Asthma has a strong hereditary link. Factors that can trigger an attack include:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree