Assisting in Orthopedic Medicine

Learning Objectives

1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary.

2. Apply critical thinking skills in performing patient assessment and patient care.

3. Describe the principal anatomic structures of the musculoskeletal system and their functions.

4. Differentiate among tendons, bursae, and ligaments.

5. Summarize the major muscular disorders.

6. Identify and describe the common types of fractures.

7. Explain the difference between osteomalacia and osteoporosis.

8. Classify typical spinal column disorders.

9. Differentiate among the various joint disorders.

10. Summarize the medical assistant’s role in assisting with orthopedic procedures.

11. Explain the common diagnostic procedures used in orthopedics.

12. Compare and contrast therapeutic modalities used in orthopedic medicine.

13. Apply cold therapy to an injury.

14. Assist with hot moist heat application to an orthopedic injury.

15. Properly apply therapeutic ultrasound.

16. Explain the use of common ambulatory devices.

17. Properly fit a patient with crutches and explain the correct mechanics of crutch walking.

18. Prepare for and assist with the application of a cast.

19. Prepare for and assist with the removal of a cast.

20. Summarize patient education guidelines for orthopedic patients.

21. Discuss the legal and ethical implications in an orthopedic practice.

Vocabulary

arthritis Inflammation of a joint.

articular (ar-ti′-kyuh-luhr) Pertaining to a joint.

bursae (bur′-suh) Fluid-filled, saclike membranes that provide cushioning and allow frictionless motion between two tissues.

cartilage A rubbery, smooth, somewhat elastic connective tissue that covers the ends of bones.

cervical (ser′-vi-kuhl) Pertaining to the neck region containing seven cervical vertebrae.

corticosteroids Antiinflammatory hormones, natural or synthetic.

crepitation (kre-puh-ta′-shun) A dry, crackling sound or sensation.

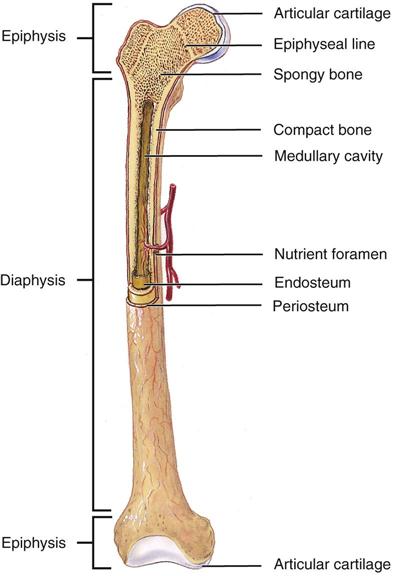

diaphysis (di-a′-fuh-suhs) The midportion of a long bone; it contains the medullary cavity.

epiphysis (i-pi′-fuh-suhs) The end of a long bone; it contains the growth (epiphyseal) plates.

goniometer An instrument for measuring the degrees of motion in a joint.

inflammation A tissue reaction to trauma or disease that includes redness, heat, swelling, and pain.

kyphotic (kahy-fot′-ik) Relating to the normal convex curvature of the thoracic spine.

lordotic (lor-do′-tik) Relating to the normal concave curvature of the cervical and lumbar spines.

lumbar Relating to the lower back region that contains the five lumbar vertebrae.

luxation Dislocation of a bone from its normal anatomic location.

malaise (muh-laz′) An indefinite feeling of debility or lack of health, often indicative of or accompanying the onset of an illness.

medullary cavity The inner portion of the diaphysis; it contains the bone marrow.

periosteum The thin, highly innervated, membranous covering of a bone.

prosthesis (prahs-the′-suhs) An artificial replacement for a body part.

reduction The return to correct anatomic position, as in reduction of a fracture.

scoliosis An abnormal lateral curvature of the spine.

synovial fluid A clear fluid found in joint cavities that facilitates smooth movements and nourishes joint structures.

tendons Tough bands of connective tissue that connect muscle to bone.

Scenario

Kaiwan Tillman became interested in orthopedics before he even knew what the word meant. In the sixth grade, he broke his right femur in a bicycle accident. He spent 2 months in traction in the hospital on an orthopedic floor. On graduation from high school, he attended the local community college and enrolled in a medical assisting program that offered an associate’s degree. Since earning his CMA (AAMA), Kaiwan has worked in a sports medicine clinic. The clinic staff at Sport Medicine Associates includes three orthopedic surgeons, two physical therapists, and two massage therapists. Kaiwan is very excited about working in the clinic, although he initially was somewhat intimidated. Dr. Steve Alexander is the team physician for a local professional baseball team, and Kaiwan’s responsibilities include assisting Dr. Alexander with treating the team.

While studying this chapter, think about the following questions:

• What are the primary responsibilities of the medical assistant in an orthopedic practice?

• What clinical skills are required in this specialty practice?

• What diagnostic and treatment procedures typically are used in an orthopedic practice?

A physician who specializes in orthopedics diagnoses and treats diseases and disorders of the musculoskeletal system and deals primarily with the bones. Rheumatologists are specialists in treating inflammatory joint disorders. Chiropractors are doctors of chiropractic (DC) but are not medical physicians; they use manual adjusting procedures to correct subluxations or misalignments of the spine to allow maximum nerve function, thus facilitating the body’s ability to maintain homeostasis and prevent disease.

The musculoskeletal system includes all of the skeletal muscles, bones, joints, and supportive connective tissues (cartilage, tendons, and ligaments). The general functions of the musculoskeletal system are:

Anatomy and Physiology of the Musculoskeletal System

Muscles

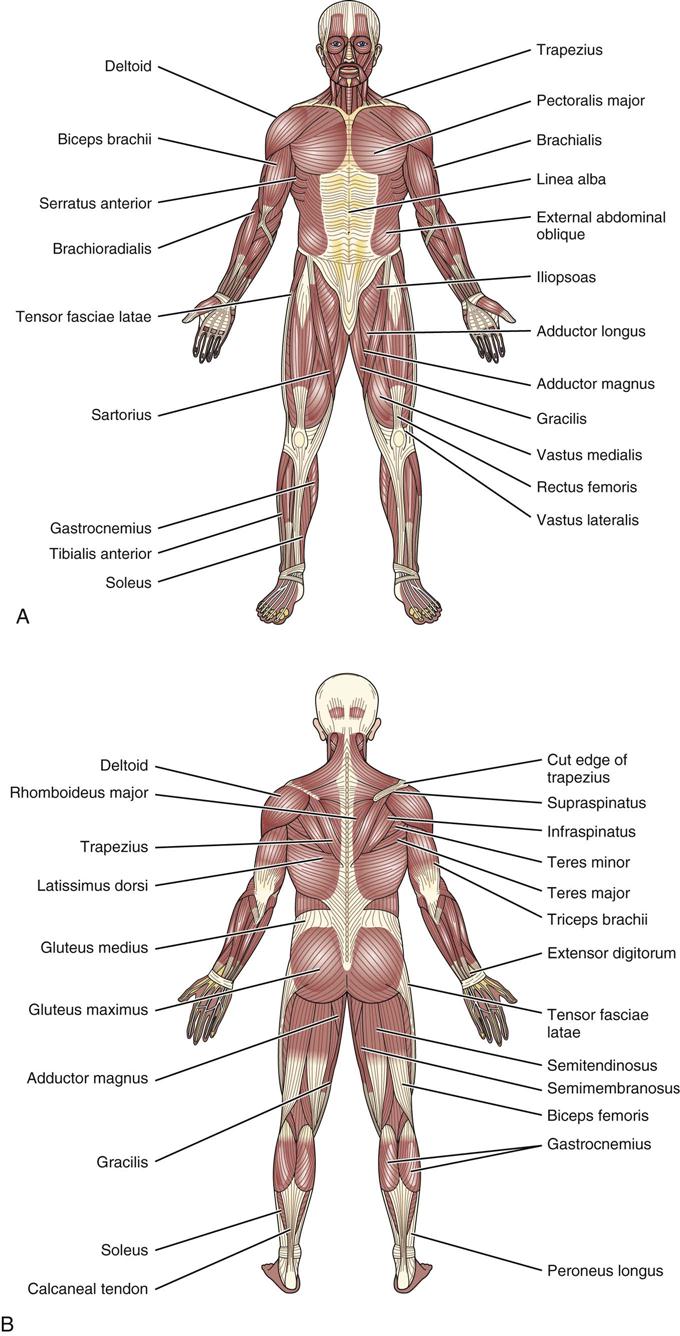

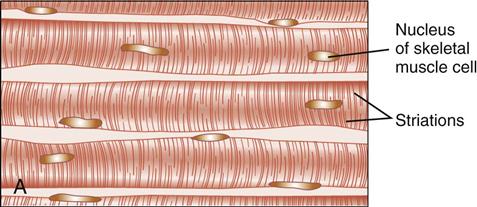

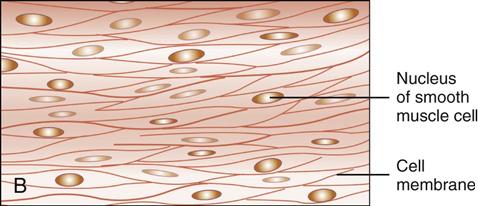

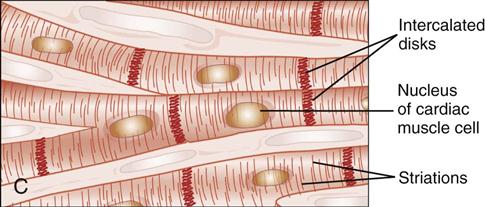

More than 600 muscles attach to the human skeleton (Figure 43-1). These muscles account for approximately half of a person’s weight, and they contribute to the body’s distinct shape. This chapter discusses the skeletal muscles that attach to bones and allow movement. Skeletal muscle fibers are voluntary and striated (Figure 43-2, A). The body has two other types of muscle: smooth muscle (Figure 43-2, B), which lines organs and blood vessel walls and is nonstriated, and cardiac muscle (Figure 43-2, C), a striated muscle in the heart. Both of these types are involuntary muscles; that is, the individual cannot control their function. Skeletal muscles are voluntary and can be controlled when they contract or relax. Special fibers in skeletal muscles allow them to shorten (contract) and lengthen (relax), which creates movement (Table 43-1). These muscles are connected to bone with bands of tough, fibrous connective tissues called tendons.

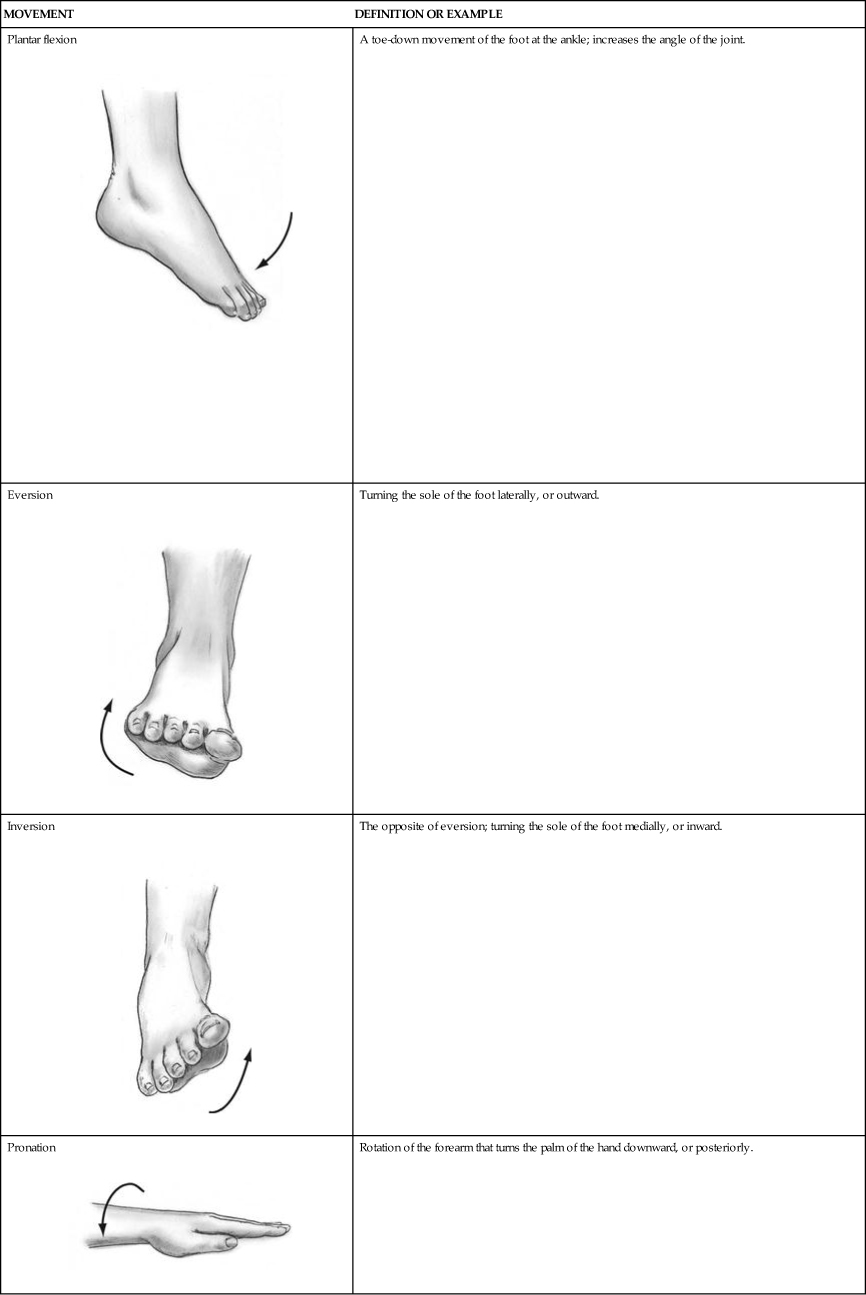

TABLE 43-1

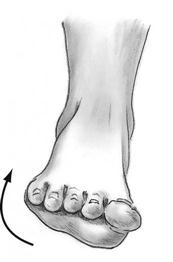

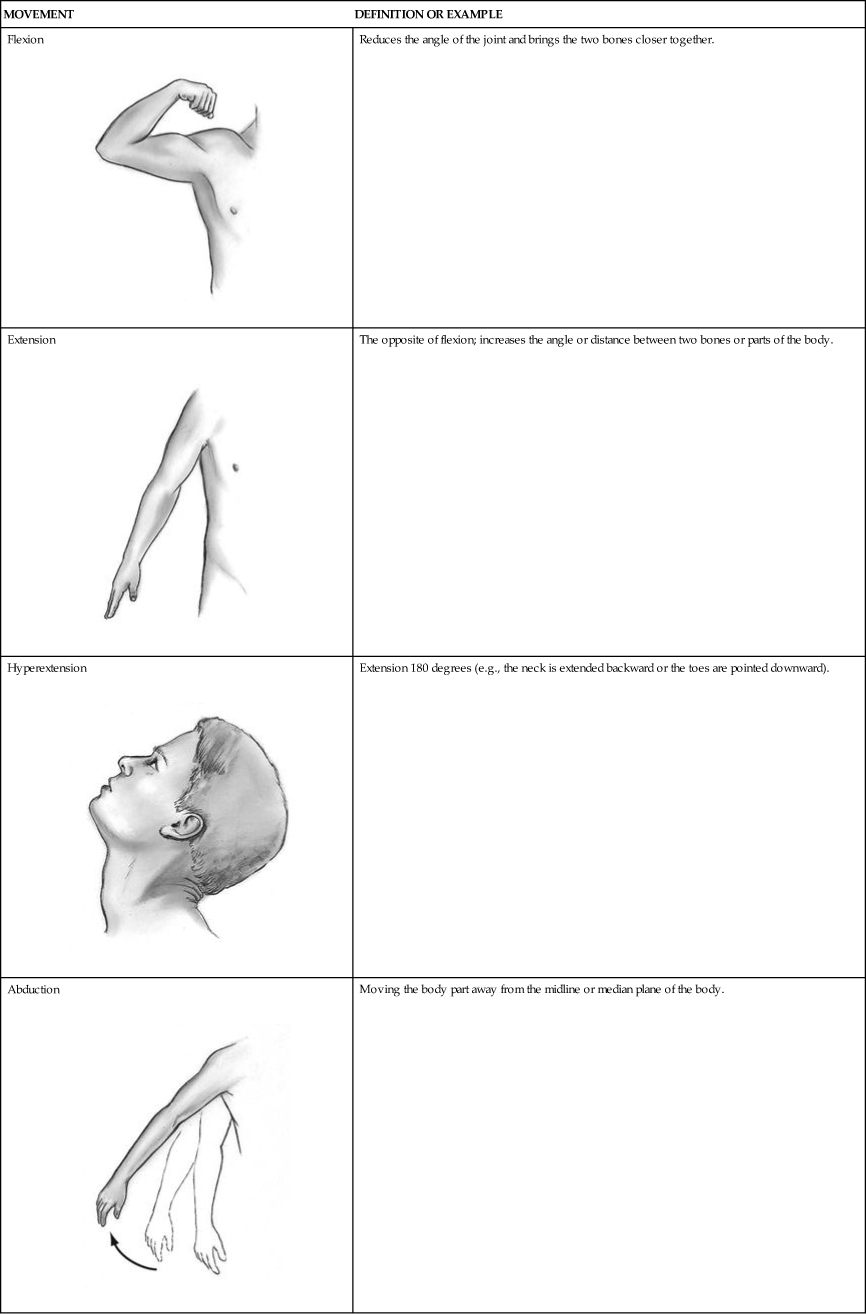

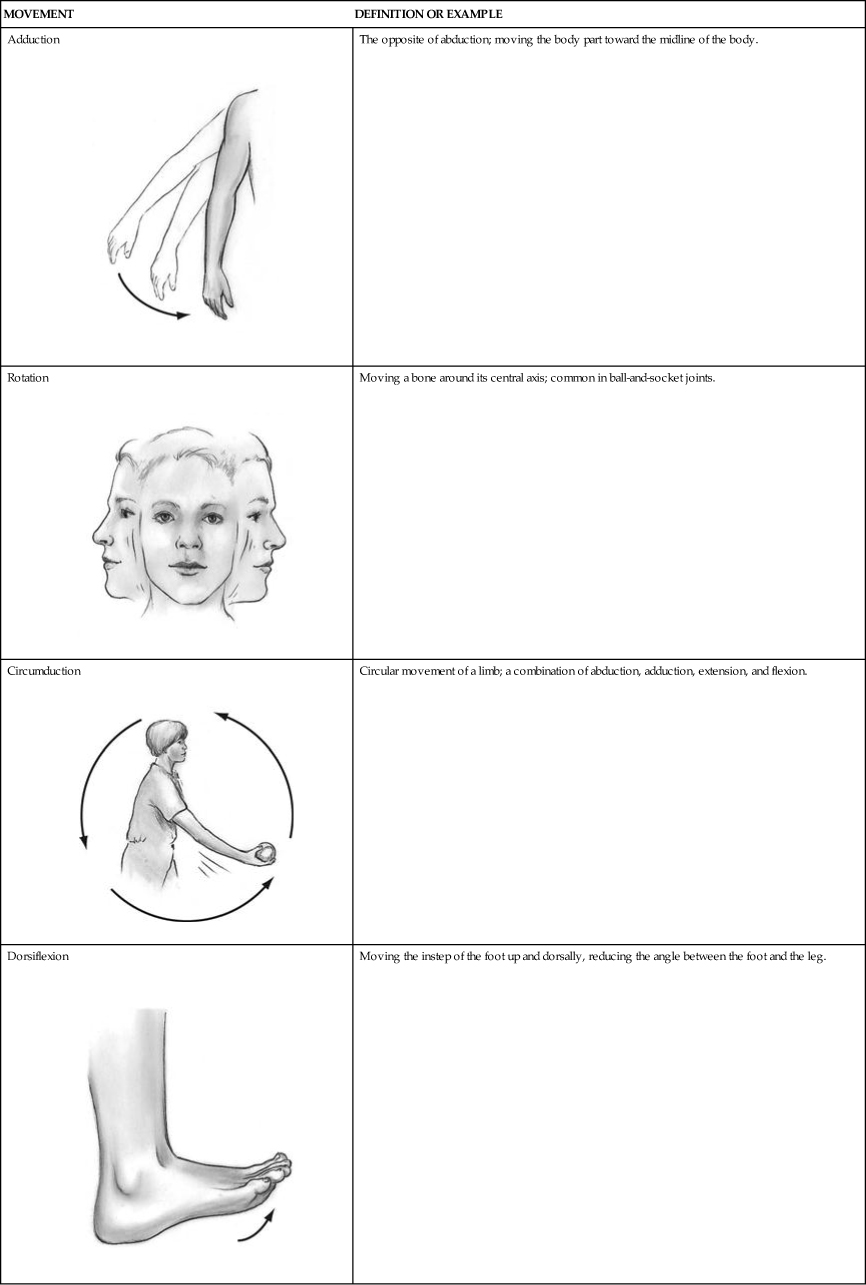

| MOVEMENT | DEFINITION OR EXAMPLE |

Flexion | Reduces the angle of the joint and brings the two bones closer together. |

Extension | The opposite of flexion; increases the angle or distance between two bones or parts of the body. |

Hyperextension | Extension 180 degrees (e.g., the neck is extended backward or the toes are pointed downward). |

Abduction | Moving the body part away from the midline or median plane of the body. |

Adduction | The opposite of abduction; moving the body part toward the midline of the body. |

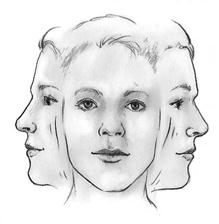

Rotation | Moving a bone around its central axis; common in ball-and-socket joints. |

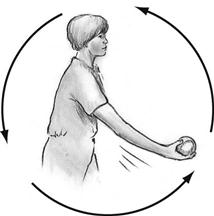

Circumduction | Circular movement of a limb; a combination of abduction, adduction, extension, and flexion. |

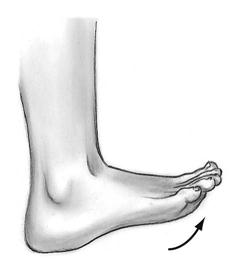

Dorsiflexion | Moving the instep of the foot up and dorsally, reducing the angle between the foot and the leg. |

Plantar flexion | A toe-down movement of the foot at the ankle; increases the angle of the joint. |

Eversion | Turning the sole of the foot laterally, or outward. |

Inversion | The opposite of eversion; turning the sole of the foot medially, or inward. |

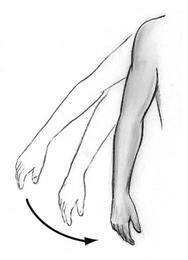

Pronation | Rotation of the forearm that turns the palm of the hand downward, or posteriorly. |

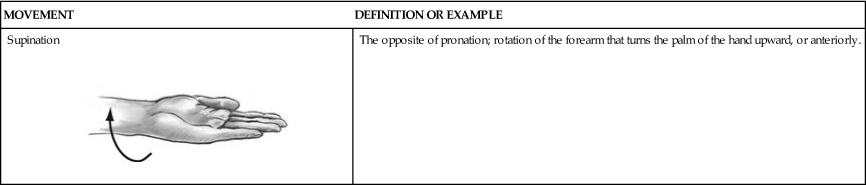

Supination | The opposite of pronation; rotation of the forearm that turns the palm of the hand upward, or anteriorly. |

Bones

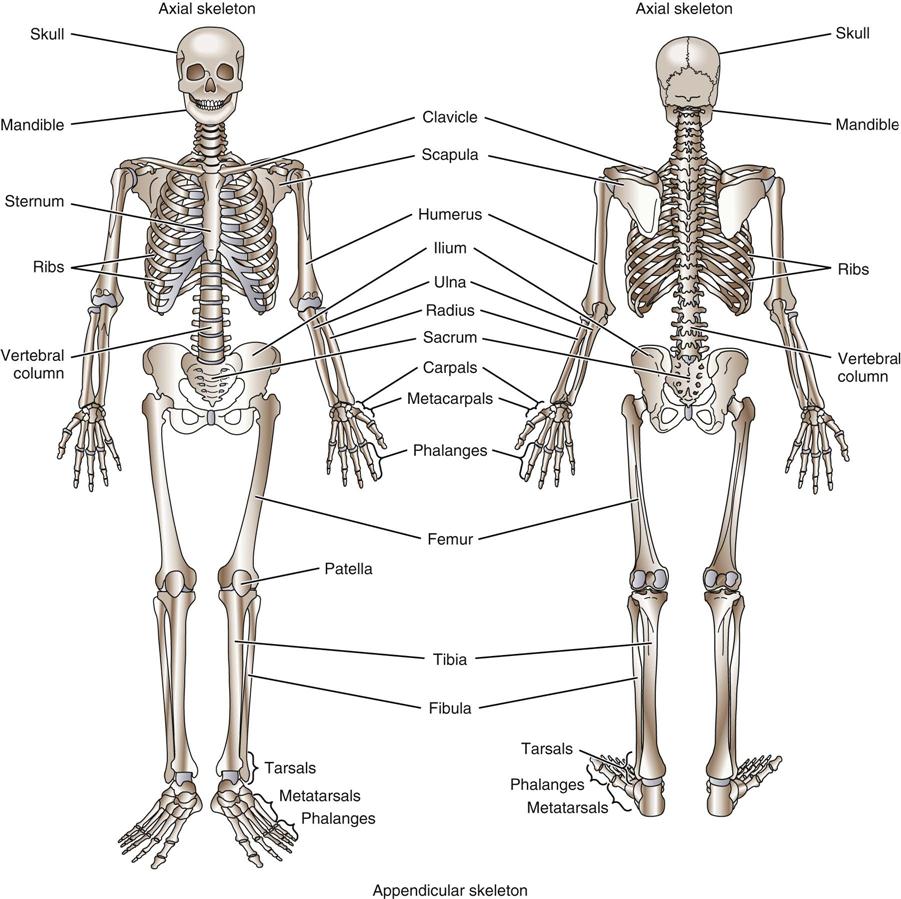

The human skeleton is composed of more than 200 bones (Figure 43-3). Bones provide a framework that protects vital organs. In general, the size and shape of a bone is related either to how much it moves and how much body weight it must carry or to its protective function for the underlying organs.

Bones generally are categorized by shape: long, short, flat, rounded, or irregular. A long bone is made up of a diaphysis (shaft) with an expansion at each end called an epiphysis (Figure 43-4). The epiphysis is covered with articular cartilage and is attached by ligaments to the epiphysis of another bone, forming a joint. Articular cartilage reduces the stress of weight bearing and the friction of movement. The thickness of the cartilage depends largely on the amount of stress placed on a particular joint. The medullary cavity, located within the diaphysis, contains yellow bone marrow.

Bone is living tissue that is constantly being remodeled in response to stress or injury. It also is a storage location for minerals, including calcium and phosphorus. Red bone marrow produces blood cells and is found in the spongy (cancellous) bone of the proximal epiphyses of the humerus and femur, sternum, ribs, and vertebrae of adults. Bones are covered with a thin, membranous tissue, the periosteum, which contains many sensory nerves.

Joints

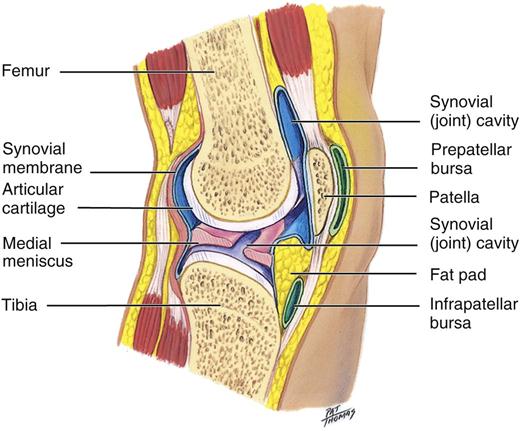

Bones are connected to each other at junctions known as joints. The two main kinds of joints are nonsynovial joints and synovial joints. In nonsynovial joints, the bones are joined with fibrous cartilage and are immovable (e.g., the sutures of the skull) or only slightly moveable (e.g., the vertebrae). Synovial joints are freely moveable, because the adjacent ends of two bones are covered with cartilage and are enclosed in a joint cavity that contains a viscous, slippery fluid called synovial fluid, which is an excellent lubricant. Synovial joints such as the elbow and the knee are hinge joints, which allow movement in only one plane (Figure 43-5). Other synovial joints, such as the hip and shoulder, allow movement in many planes, which permits a wider range of motion (ROM) than a hinge joint.

Types of Joints

Joints are classified by the way they are shaped or by their ability to move. The joints of the skull are known as sutures. Sutures permit the skull to grow with the child but have very limited flexibility. As mentioned, the hinge joints of the elbow and knee allow for movement in one plane, such as bending back and forth. A gliding joint, as in the wrist and foot, is made up of two flat-surfaced bones that slide over each other, allowing limited movement. Ball-and-socket joints, as in the shoulder and hip, allow for the greatest ROM by permitting the joint to rotate in a complete circle. Artificial joints have been successfully implanted to replace joints that have been damaged by disease or trauma, including the joints of the hip, knee, ankle, shoulder, elbow, wrist, and finger.

Ligaments, Tendons, and Bursae

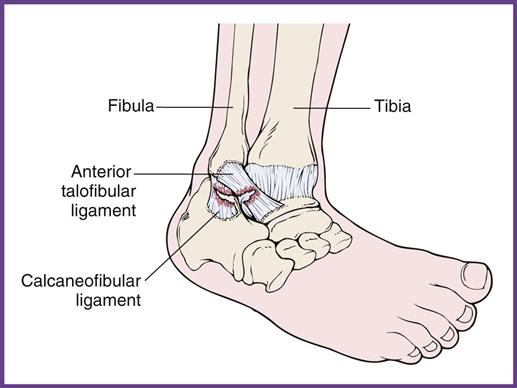

Ligaments are powerful, strong, fibrous bands of connective tissue that connect bone to bone at the joint and encase the joint capsule. Ligaments allow purposeful joint movement and prevent excessive movement in any particular joint. Ligaments may be oblique or parallel to the joint, as in the knee, or may surround the joint, as in the hip.

A tendon is a strong bundle of connective tissue that attaches muscle to bone. Tendons can be flat or round and can pass between muscles, between bones, or through specialized openings between bones.

Bursae are fibrous sacs that lie between tendons and bones; they are lined with synovial membranes that secrete synovial fluid and act as cushions between a bone and a tendon or between a tendon and a ligament. Bursae reduce friction and help muscles and tendons glide smoothly over bone.

Musculoskeletal Diseases and Disorders

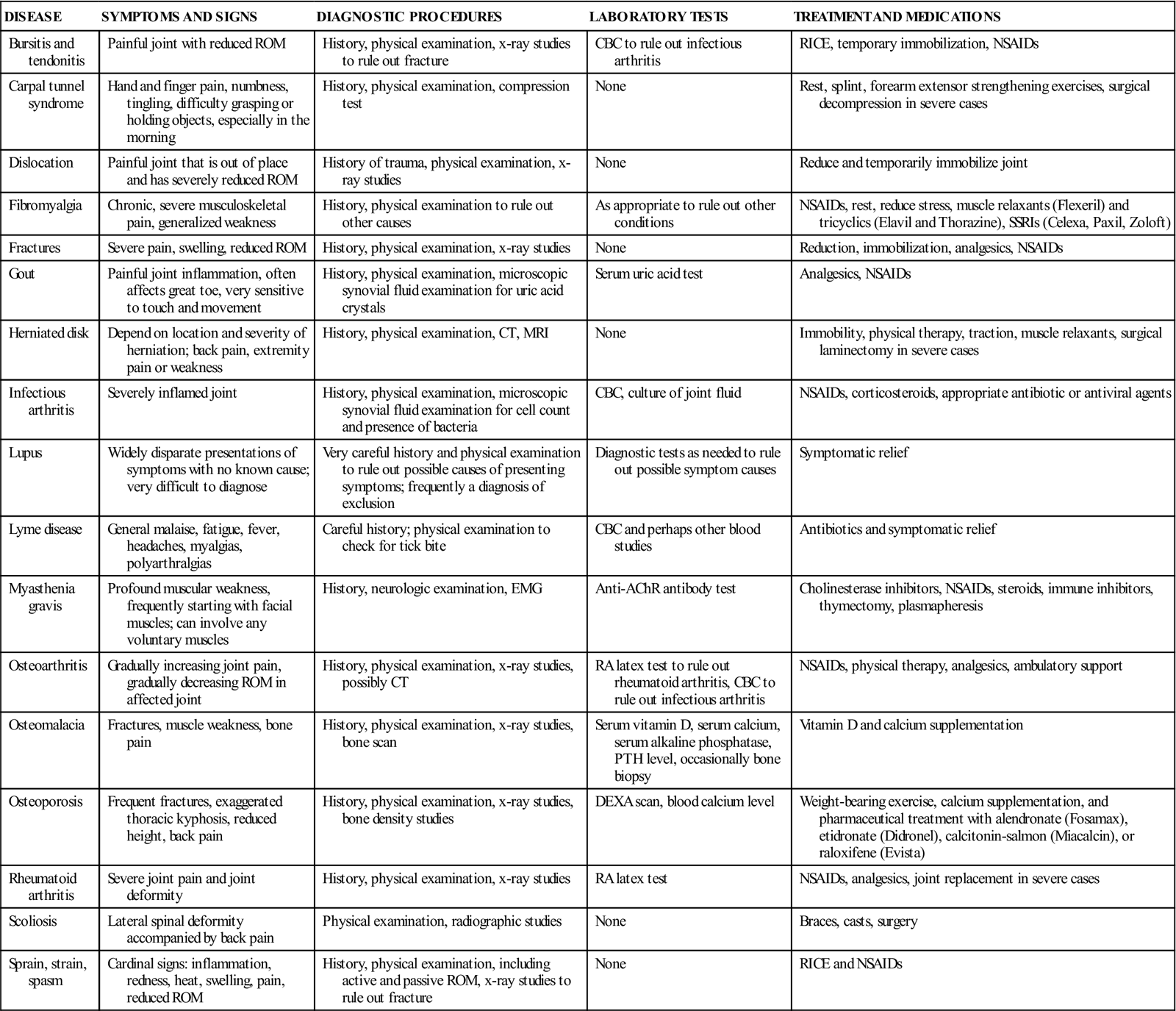

Musculoskeletal diseases and conditions can affect any of the muscles, bones, or joints. These problems are common and have a tremendous impact on an individual’s quality of life. Brittle or deformed bones that are prone to fracture often mark bone disorders such as osteoporosis and osteomalacia. Joint disorders, such as osteoarthritis (OA), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and gout, can lead to painful, swollen, or inflamed joints. Muscle problems, such as sprains and spasms, can bring on sudden pain or cause stiffness (Table 43-2).

TABLE 43-2

Common Musculoskeletal Conditions

| DISEASE | SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS | DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES | LABORATORY TESTS | TREATMENT AND MEDICATIONS |

| Bursitis and tendonitis | Painful joint with reduced ROM | History, physical examination, x-ray studies to rule out fracture | CBC to rule out infectious arthritis | RICE, temporary immobilization, NSAIDs |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | Hand and finger pain, numbness, tingling, difficulty grasping or holding objects, especially in the morning | History, physical examination, compression test | None | Rest, splint, forearm extensor strengthening exercises, surgical decompression in severe cases |

| Dislocation | Painful joint that is out of place and has severely reduced ROM | History of trauma, physical examination, x-ray studies | None | Reduce and temporarily immobilize joint |

| Fibromyalgia | Chronic, severe musculoskeletal pain, generalized weakness | History, physical examination to rule out other causes | As appropriate to rule out other conditions | NSAIDs, rest, reduce stress, muscle relaxants (Flexeril) and tricyclics (Elavil and Thorazine), SSRIs (Celexa, Paxil, Zoloft) |

| Fractures | Severe pain, swelling, reduced ROM | History, physical examination, x-ray studies | None | Reduction, immobilization, analgesics, NSAIDs |

| Gout | Painful joint inflammation, often affects great toe, very sensitive to touch and movement | History, physical examination, microscopic synovial fluid examination for uric acid crystals | Serum uric acid test | Analgesics, NSAIDs |

| Herniated disk | Depend on location and severity of herniation; back pain, extremity pain or weakness | History, physical examination, CT, MRI | None | Immobility, physical therapy, traction, muscle relaxants, surgical laminectomy in severe cases |

| Infectious arthritis | Severely inflamed joint | History, physical examination, microscopic synovial fluid examination for cell count and presence of bacteria | CBC, culture of joint fluid | NSAIDs, corticosteroids, appropriate antibiotic or antiviral agents |

| Lupus | Widely disparate presentations of symptoms with no known cause; very difficult to diagnose | Very careful history and physical examination to rule out possible causes of presenting symptoms; frequently a diagnosis of exclusion | Diagnostic tests as needed to rule out possible symptom causes | Symptomatic relief |

| Lyme disease | General malaise, fatigue, fever, headaches, myalgias, polyarthralgias | Careful history; physical examination to check for tick bite | CBC and perhaps other blood studies | Antibiotics and symptomatic relief |

| Myasthenia gravis | Profound muscular weakness, frequently starting with facial muscles; can involve any voluntary muscles | History, neurologic examination, EMG | Anti-AChR antibody test | Cholinesterase inhibitors, NSAIDs, steroids, immune inhibitors, thymectomy, plasmapheresis |

| Osteoarthritis | Gradually increasing joint pain, gradually decreasing ROM in affected joint | History, physical examination, x-ray studies, possibly CT | RA latex test to rule out rheumatoid arthritis, CBC to rule out infectious arthritis | NSAIDs, physical therapy, analgesics, ambulatory support |

| Osteomalacia | Fractures, muscle weakness, bone pain | History, physical examination, x-ray studies, bone scan | Serum vitamin D, serum calcium, serum alkaline phosphatase, PTH level, occasionally bone biopsy | Vitamin D and calcium supplementation |

| Osteoporosis | Frequent fractures, exaggerated thoracic kyphosis, reduced height, back pain | History, physical examination, x-ray studies, bone density studies | DEXA scan, blood calcium level | Weight-bearing exercise, calcium supplementation, and pharmaceutical treatment with alendronate (Fosamax), etidronate (Didronel), calcitonin-salmon (Miacalcin), or raloxifene (Evista) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Severe joint pain and joint deformity | History, physical examination, x-ray studies | RA latex test | NSAIDs, analgesics, joint replacement in severe cases |

| Scoliosis | Lateral spinal deformity accompanied by back pain | Physical examination, radiographic studies | None | Braces, casts, surgery |

| Sprain, strain, spasm | Cardinal signs: inflammation, redness, heat, swelling, pain, reduced ROM | History, physical examination, including active and passive ROM, x-ray studies to rule out fracture | None | RICE and NSAIDs |

Trauma to the musculoskeletal system can quickly lead to inflammation in the area of injury. This type of injury is one of the leading causes of time lost from work and for visits to primary care physicians and emergency departments. As soon as possible after injury, even before a patient is seen by a physician, treatment involving rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE therapy) should be started. The combination of these measures can help reduce swelling and inflammation and enhance healing.

To maintain musculoskeletal health, a person must have a significant dietary intake of foods rich in calcium and vitamin D, avoid smoking, and include weight-bearing exercises (e.g., walking) in the daily routine. In addition to these lifestyle measures, medications sometimes are required for conditions that impair normal functioning of this system. The conditions discussed in the following sections are typically seen in an orthopedic practice.

Muscular Disorders

Fibromyalgia

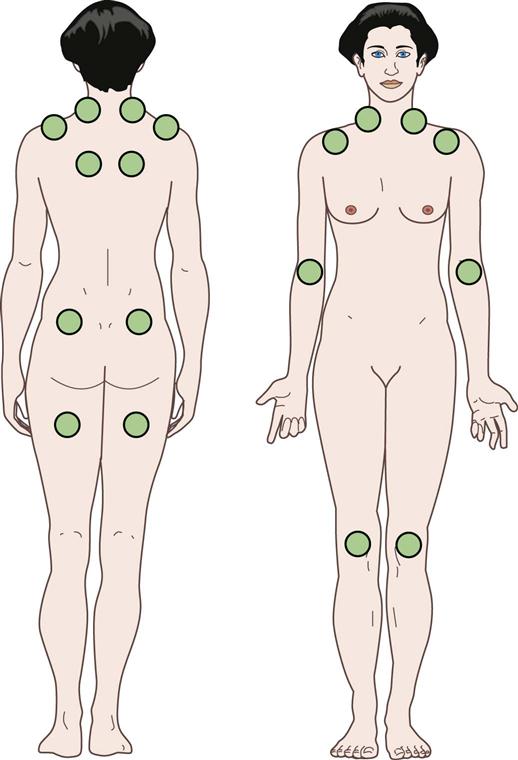

Fibromyalgia is a condition of widespread connective tissue and muscular pain and often includes severe fatigue of unknown origin. A patient with fibromyalgia usually complains of diffuse aches and pains all over the body. The disorder can affect people of all ages and is seen more frequently in women than in men. Chronic pain and fatigue are the cardinal signs in the absence of any other known cause. Associated conditions can include sleep disorders, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic headaches, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) problems, increased chemical sensitivity, and other musculoskeletal complaints.

Although the cause remains unknown, fibromyalgia can be triggered by an automobile accident or a bacterial or viral infection, or it can follow the diagnosis of other medical conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or hypothyroidism. It is aggravated by changes in the weather or temperature, monthly hormonal variations, stress, anxiety, and depression. The diagnosis is made by eliminating any other cause for the symptoms and by finding 11 of 18 specific points to be extremely tender to palpation (Figure 43-6). Treatment goals include reducing pain, enhancing sleep, and reducing anxiety and stress. Pregabalin (Lyrica), an antiseizure medication, is the first drug that has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat fibromyalgia. Prescription sleeping pills, such as zolpidem (Ambien), are prescribed only for the short term, because the body eventually becomes tolerant to the medication, rendering it ineffective. Other medical treatments include over-the-counter analgesics and antiinflammatory agents, such as Tylenol or ibuprofen; tramadol (Ultram) for relief of pain; and antidepressants, such as duloxetine (Cymbalta) and milnacipran (Savella), to ease the pain and fatigue associated with fibromyalgia and fluoxetine (Prozac) to help promote sleep. Stress reduction and relaxation exercises help control symptoms. Fibromyalgia has no known cure.

Myasthenia Gravis

Myasthenia gravis is a chronic autoimmune neuromuscular disease of unknown origin that affects voluntary muscle contraction. It can occur at any age but most frequently affects young adult women (under age 40) and older men (over age 60). Often the patient experiences a sudden onset of weakness in the muscles that control eye and eyelid movement, facial expression, and swallowing. Symptoms vary in type and severity and may include drooping of one or both eyelids (ptosis); blurred or double vision (diplopia) as a result of weakness of the muscles that control eye movements; an unstable or waddling gait; weakness in the arms, hands, fingers, legs, and neck; altered facial expressions; difficulty swallowing; shortness of breath; and impaired speech (dysarthria).

Myasthenia gravis is caused by a defect in the transmission of nerve impulses to muscles. It occurs when a nervous stimulus is unable to stimulate a muscle at the neuromuscular junction, the place where nerve cells connect with the muscles they control. Normally, when impulses travel down the nerve, the nerve endings release acetylcholine (ACh), a neurotransmitter that activates muscular contraction. In myasthenia gravis, antibodies block, alter, or destroy the receptors for ACh at the neuromuscular junction, which prevents the muscle contraction. The primary treatment is a medication that inhibits acetylcholinesterase, the enzyme that normally breaks down ACh. This allows ACh to remain at the neuromuscular junction longer than usual so that more of the remaining receptor sites can be activated. Surgical removal of the thymus gland (thymectomy) reduces symptoms in most patients and may cure some individuals. Spontaneous improvement and remissions can occur.

Sprains, Strains, and Spasms

A sprain is a wrenching or twisting of a joint in an abnormal plane of motion or beyond its normal ROM that results in stretching and/or tearing of a ligament. Concurrent damage to area blood vessels, muscles, tendons, and nerves may occur. Probably the most common sprain is the ankle sprain (Figure 43-7), which can occur when a person steps off a curb or into a small depression and twists the ankle. Severe sprains are so painful the joint cannot be used, and they are accompanied by swelling and reddish to bluish discoloration because of ruptured blood vessels in the area.

A strain may be a simple overstretching of a muscle or tendon, or it can be caused by a partial or complete tear of the tissue away from the bone.

These soft tissue injuries are diagnosed by a comprehensive history and physical examination. Usually x-ray films are taken to rule out fractures. Treatment includes RICE: rest of the injured joint with no weight bearing to prevent further damage; cold application for 20 minutes at a time, four to eight times a day, during the first 24 to 48 hours to reduce pain and swelling; compression with an elastic wrap or air cast to reduce swelling; and elevation of the injured part. The physician also may recommend the use of over-the-counter (OTC) antiinflammatory drugs such as aspirin or ibuprofen to help reduce pain and inflammation at the site. If severe soft tissue injury occurs, immobilization by casting, surgical repair, or both may be required.

Treatment of a sprain or strain may also include rehabilitative exercises. The physician typically prescribes an exercise program designed to prevent stiffness, improve the joint’s ROM, and restore normal flexibility and strength. Some patients may also be referred to physical therapy for complete return of function after the initial pain and swelling have subsided.

Muscle spasms occur spontaneously and may persist for hours. They typically are caused by heavy exercise and muscle fatigue, but they also can be caused by dehydration, hypothyroidism, lack of calcium or magnesium, kidney failure, and alcoholism. Muscle spasms can be quite painful. Treatment includes massage, direct pressure, ultrasound therapy, stress reduction, stretching exercises, and muscle relaxants in some cases.

Skeletal Disorders

Fractures

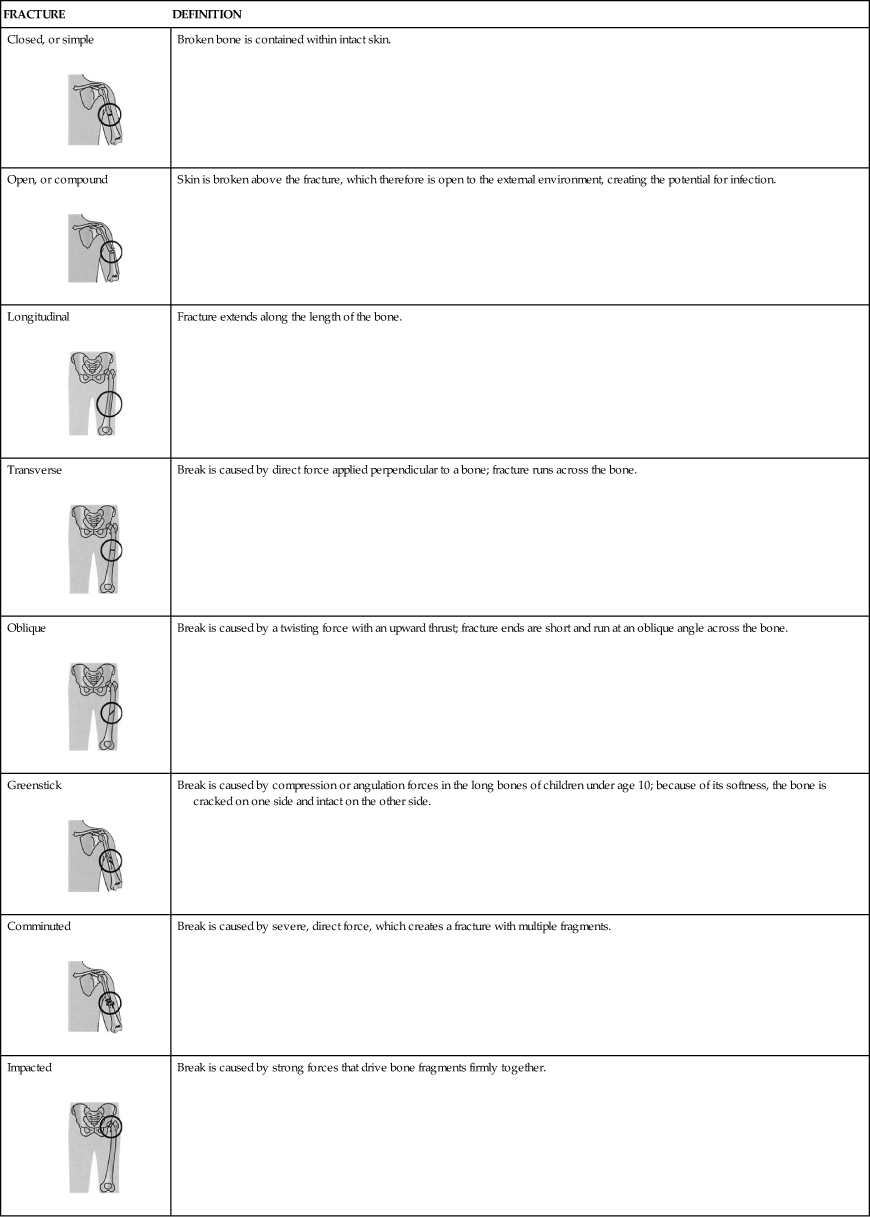

A fracture is a break or crack in a bone that generally is the result of trauma or disease. Many different types of fractures occur, and each produces its own set of problems (Table 43-3). The common symptom of all fractures is pain. Other symptoms may include swelling, bleeding, inability to move, misalignment of the bone, and discoloration of the immediate area.

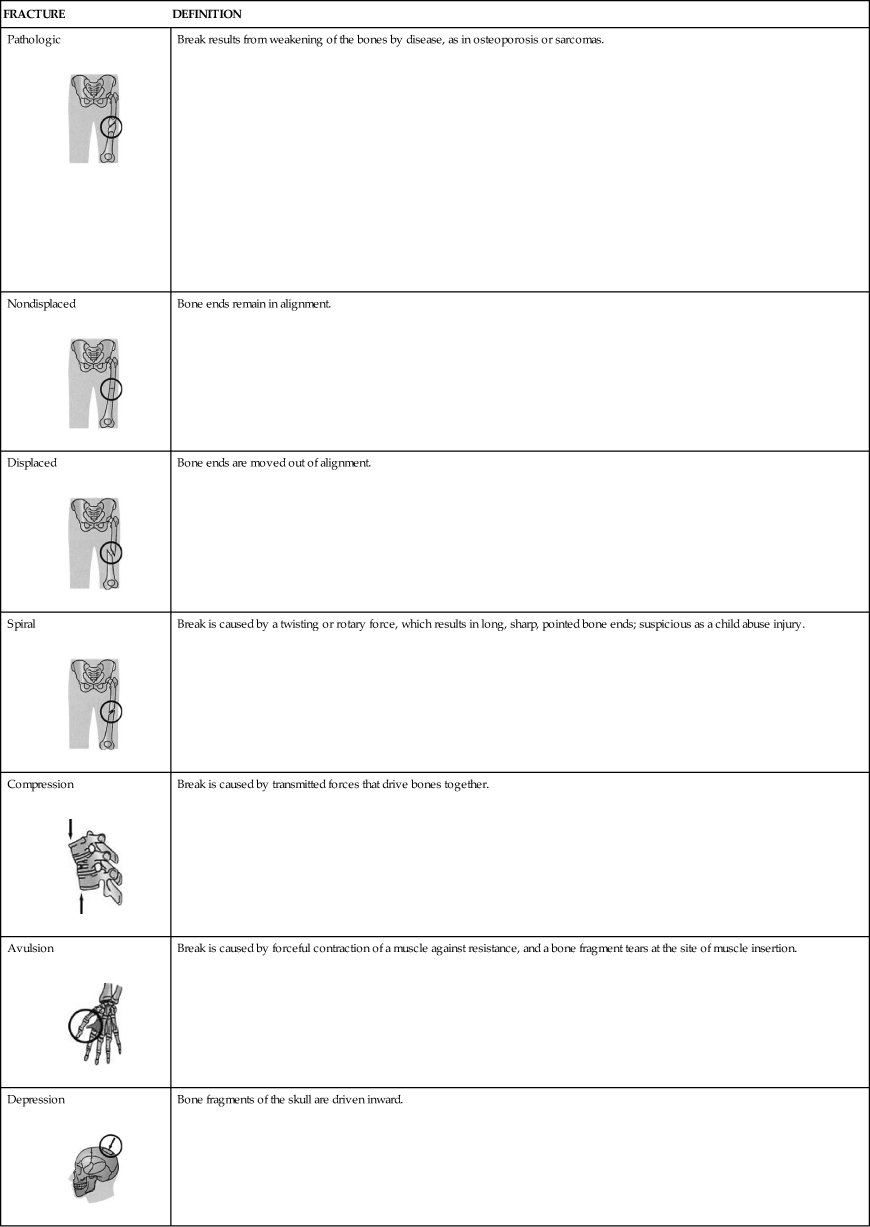

TABLE 43-3

| FRACTURE | DEFINITION |

Closed, or simple | Broken bone is contained within intact skin. |

Open, or compound | Skin is broken above the fracture, which therefore is open to the external environment, creating the potential for infection. |

Longitudinal | Fracture extends along the length of the bone. |

Transverse | Break is caused by direct force applied perpendicular to a bone; fracture runs across the bone. |

Oblique | Break is caused by a twisting force with an upward thrust; fracture ends are short and run at an oblique angle across the bone. |

Greenstick | Break is caused by compression or angulation forces in the long bones of children under age 10; because of its softness, the bone is cracked on one side and intact on the other side. |

Comminuted | Break is caused by severe, direct force, which creates a fracture with multiple fragments. |

Impacted | Break is caused by strong forces that drive bone fragments firmly together. |

Pathologic | Break results from weakening of the bones by disease, as in osteoporosis or sarcomas. |

Nondisplaced | Bone ends remain in alignment. |

Displaced | Bone ends are moved out of alignment. |

Spiral | Break is caused by a twisting or rotary force, which results in long, sharp, pointed bone ends; suspicious as a child abuse injury. |

Compression | Break is caused by transmitted forces that drive bones together. |

Avulsion | Break is caused by forceful contraction of a muscle against resistance, and a bone fragment tears at the site of muscle insertion. |

Depression | Bone fragments of the skull are driven inward. |

From Chester GA: Modern medical assisting, Philadelphia, 1999, WB Saunders.

When a patient with a suspected fracture comes into the office, you should make the person as comfortable as possible. First aid includes RICE; positioning the patient to prevent stress on the injured area; elevating the injured extremity if possible; and controlling any bleeding but never applying pressure over a suspected fracture. Do not attempt to straighten the fracture or move it in any way. If the patient must be moved, either apply a splint or support the joints above and below the suspected fracture before and while moving the patient. The fracture must be confirmed by x-ray examination as soon as possible.

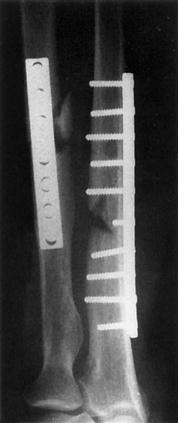

Treatment includes reduction, if necessary, and immobilization. Reduction places the fractured bone back into its correct anatomic alignment. Reduction may be closed or open. In a closed reduction, the physician manipulates the bone into its correct position. If this is not possible or if the fractured bones have pierced the skin, an open reduction is required, which is surgical realignment of the bone. During an open reduction, the orthopedic surgeon may have to install metal pins, plates, or screws to facilitate and maintain correct bone alignment. These metal implants may be temporary or permanent, depending on the extent of injury (Figure 43-8). After the fracture has been reduced, it must be immobilized by splinting, casting, taping, or wrapping the area to prevent movement of the fracture site and thereby facilitate healing.

Osteomalacia

The term osteomalacia literally means “softening of the bones.” Osteomalacia is a metabolic disease in which inadequate calcium or phosphorus (or both) is available for building new bone during growth or remodeling. It is caused by either a lack of vitamin D or problems with its metabolism. The skeleton gradually loses calcium, and the bones soften and become more flexible. Weight bearing gradually changes the shape of the softened bones. Symptoms can include reduced endurance, easy fatigability, malaise, and generalized bone tenderness and pain. Osteomalacia in children is called rickets.

Osteomalacia may be caused by a fat absorption problem in the gastrointestinal tract that prevents adequate absorption of dietary fats, resulting in steatorrhea and vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D promotes the body’s absorption of calcium, which is essential for normal development and maintenance of healthy teeth and bones. Vitamin D can be produced by the body with adequate sun exposure, and nearly all milk sold in the United States is fortified with vitamin D. Osteomalacia can occur in individuals who use very strong sunscreen, have limited exposure to sunlight, experience short days of sunlight, live in a smoggy environment, or do not drink milk because of lactose intolerance. The condition is treated with vitamin D, calcium, and phosphorus supplements.

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a disease in which calcium deposits in the bone gradually decline, and bones become increasingly weak and brittle so that even small stressors, such as bending over or coughing, can cause fractures. Bone strength depends on the size and density of the bone structure and the amount of calcium, phosphorus, and other materials deposited and maintained in the bone. Bones are constantly changing through a process called remodeling, or bone turnover. This process allows bones to grow and heal. As we age, remodeling breaks down bone more quickly than it forms new bone. Peak bone mass is reached by the middle 30s, so a person’s risk of developing osteoporosis depends on the bone mass collected by age 25 to 35 and how rapidly bone tissue is lost after that. Lack of vitamin D and calcium in the diet results in a lower peak bone mass and a more rapid onset of bone loss later in life. People over age 50 are particularly at risk, and women are four times more likely to develop osteoporosis than men. Osteoporosis is a major public health threat in the United States, affecting more than 40 million individuals.

Osteoporosis often is called the “silent disease,” because the progressive loss of bone density occurs without any symptoms. Osteopenia is mild bone loss that is not severe enough to be called osteoporosis but that increases the risk of osteoporosis. By the time fractures occur, the disease is quite advanced. Patients with osteoporosis complain of back pain because of a fractured or collapsed vertebra; loss of height over time, with stooped posture (kyphosis, or “dowager’s hump”); and fractures typically of the vertebrae, wrists, and hips. Risk factors include being a postmenopausal woman over age 50; a slight build with a family history of osteoporosis; a history of amenorrhea; a low dietary calcium intake; an excessive intake of caffeinated soda; an inactive lifestyle; smoking; alcohol abuse; hyperthyroidism; a reduced lifetime exposure to estrogen; and long-term treatment with certain medications, including antiseizure drugs, corticosteroids, and heparin. Men over age 50 with low testosterone levels also are at risk. Osteoporosis occurs in all races but is slightly more common in Caucasian and Asian individuals.

The diagnosis is made by a specialized form of x-ray evaluation that specifically measures bone density. This study allows the diagnosis of osteoporosis before a fracture occurs and thus intervention to prevent fractures. Readings are repeated annually to determine the rate of bone loss and to monitor the effectiveness of treatment. Intervention and treatment include increasing dietary intake of calcium and vitamin D; increasing weight-bearing exercise; and pharmaceutical treatment with bisphosphonates (alendronate [Fosamax], risedronate [Actonel]), zoledronic acid [Reclast] and ibandronate sodium [Boniva]); raloxifene (Evista), and calcitonin-salmon (Miacalcin). The best screening test is a dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan, which measures the bone density of the spine, hip, and wrist. Other tests that can accurately measure bone density include ultrasound and quantitative computed tomography (CT) scanning.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation recommends that all women have a bone density test if they are not receiving estrogen replacement therapy and are in any of the following categories:

• Undergoing long-term treatment with medications that can cause osteoporosis, such as prednisone

• Have diabetes type 1, liver disease, kidney disease, or a family history of osteoporosis

• Experienced early menopause (in the early 40s)

• Are postmenopausal, over age 50, and have at least one risk factor for osteoporosis

• Are postmenopausal, over age 65, and have never had a bone density test

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree