1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary. 2. Apply critical thinking skills in performing patient assessment and patient care. 3. Explain the differences among an ophthalmologist, an optometrist, and an optician. 4. Identify the anatomic structures of the eye. 5. Describe the process of vision. 6. Differentiate among the major types of refractive errors. 7. Summarize typical disorders of the eye. 8. Define the various diagnostic procedures for the eye. 9. Conduct a vision acuity test using the Snellen chart. 10. Assess color acuity using the Ishihara test. 11. Explain the purpose of eye irrigations and instillation of medications. 12. Properly irrigate a patient’s eyes. 13. Accurately instill eye medication. 14. Identify the structures and explain the functions of the external, middle, and inner ear. 16. Define the major disorders of the ear, including otitis, impacted cerumen, and Ménière’s disease. 17. Explain diagnostic procedures for the ear. 18. Use an audiometer to accurately measure the hearing acuity of a patient. 19. Identify the purpose of ear irrigations and instillation of ear medications. 20. Demonstrate the procedure for performing ear irrigations. 21. Accurately instill medicated ear drops. 22. Summarize the nose and throat examination. 24. Describe the effect of sensory loss on patient education. accommodation Adjustment of the eye that allows a person to see various sizes of objects at different distances. amblyopia (am-ble-o′-pe-uh) Reduction or dimness of vision with no apparent organic cause; often referred to as lazy eye syndrome. audiologist (au-de-ah′-lah-jist) Allied healthcare professional who specializes in evaluation of hearing function, detection of hearing impairment, and determination of the anatomic site of impairment. cones Structures in the retina that make the perception of color possible. fovea centralis (fo′-ve-uhl/sen-trah′-luhs) Small pit in the center of the retina that is considered the center of clearest vision. gonioscopy (goh-nee-os′-kuh-pee) Procedure in which a mirrored optical instrument is used to visualize the filtration angle of the anterior chamber of the eye; the procedure is used to diagnose glaucoma. hertz Unit of measurement used in hearing examinations; a wave frequency equal to 1 cycle per second. miotic (mi-ah′-tik) Any substance or medication that causes constriction of the pupil. mydriatic (mid-ree-at′-ik) Topical ophthalmic medication that dilates the pupil; it is used in diagnostic procedures of the eye and as treatment for glaucoma. optic nerve The second cranial nerve, which carries impulses for the sense of sight. otosclerosis (o-tuh-skluh-ro′-suhs) The formation of spongy bone in the labyrinth of the ear, which often causes the auditory ossicles to become fixed and unable to vibrate when sound enters the ears. ototoxic (o-tuh-tahk′-sik) Medicine or substance capable of damaging the eighth cranial nerve or the organs of hearing and balance. psoriasis (suh-ri′-uh-suhs) A usually chronic, recurrent skin disease marked by bright red patches covered with silvery scales. rods Structures in the retina of the eye that form the light-sensitive elements. seborrhea (se-buh-re′-uh) An excessive discharge of sebum from the sebaceous glands, forming greasy scales or cheesy plugs on the body. tonometer (toh-nom′-i-ter) An instrument used to measure intraocular pressure. Kim Tau, CMA (AAMA), works in an outpatient clinic that specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of eye and ear disorders. Kim has been asked by her supervisor to help orient Amy Ling to the practice. Amy recently graduated from a medical assistant program and is familiar with basic eye and ear procedures, but she has many questions about her responsibilities at the clinic. Amy will be responsible for performing initial Snellen and Ishihara screening examinations on new patients, and for assisting the ophthalmologist and the optician in the practice with eye treatments. She also will have to be comfortable performing audiometry hearing screening on pediatric patients, performing ear irrigations, and administering otic medications. Kim recognizes that it is important that Amy be able to perform these skills with accuracy and confidence, but she also must be sensitive to the communication and patient education needs of patients with eye and ear disorders. While studying this chapter, think about the following questions: • What is the basic anatomy and physiology of the eye and of the ear? • What are the major types of refractive errors? • With what disorders of the eye and ear does Amy need to be familiar? • How is a Snellen test performed? • How is an examination with an audiometer conducted? • How should Amy perform a throat culture? • How should Kim prepare Amy to care for patients with sensory loss? A medical assistant is responsible for performing a wide variety of procedures in an ophthalmologic or otorhinolaryngologic practice. First, the medical assistant must be familiar with the normal anatomy and physiology of the eyes, ears, nose, and throat. With an understanding of how these specialty sensory organs function, the medical assistant can master the skills needed to become a valuable asset to the physician who specializes in the treatment of eye and ear disorders. This chapter covers the conditions most frequently seen in the ambulatory care setting. Many subspecialty areas are available to medical assistants in the eye, ear, nose, and throat (ENT) medical practice. Learning the fundamental procedures now will provide you with a base on which to build the advanced techniques you will need if you choose to concentrate your expertise in these areas. Ophthalmology is the science of the eye and its disorders and diseases. A physician who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of disorders and diseases of the eye is an ophthalmologist. An ophthalmologist is a licensed medical physician who can diagnose eye disorders, prescribe medication, conduct eye screenings, prescribe glasses or contact lenses, and perform optic surgery. An optometrist is not a medical doctor but is licensed and has earned a degree as a Doctor of Optometry (OD). An optometrist can perform eye examinations, diagnose vision problems and eye diseases, and treat visual defects through corrective lenses and eye exercises. Opticians are trained to fill prescriptions written by ophthalmologists and optometrists for corrective lenses by grinding the lenses and dispensing eyewear. The eyes are the smallest, yet the most detailed and complex, organs of the body. Each is located within a bony cavity (or orbit) in the skull. The bony orbit protects and supports the eye. Only approximately one-sixth of the eye lies outside the orbit. The eyelid helps protect the eye from trauma. The eyebrows help keep irritants out of the eyes. The eyelashes line the margins of the eyelids and help trap foreign particles. The conjunctiva is a thin mucous membrane that lines the eyelid and covers the outside of the eyeball except for the most central portion, which is covered by the cornea. The mucus secreted from the conjunctiva helps keep the eye moist. The eye blinks every 2 to 3 seconds, causing the lacrimal gland, located in the superior outer portion of the upper eyelid, to secrete tears. Tears move across the eyes, cleansing and moistening the surface, and drain into the lacrimal canals in the medial corner of the eye. The tears then drain into the nasal cavity through the nasolacrimal duct. Consequently, when a person cries, the excess tears ultimately empty into the nose, producing a watery nasal discharge. The eyeball consists of three layers. The outermost layer is made up of the white, opaque sclera and the transparent cornea. The sclera is a tough, fibrous lining that protects the entire eyeball lying within the orbit, whereas the transparent cornea covers the exposed one-sixth of the eyeball. The cornea acts as a clear window that allows light to enter the eye. The cornea also refracts, or changes, the direction of light rays after they enter the eye. The cornea was one of the first tissues to be transplanted, and corneal transplants now are common. Long-term success after corneal implant surgery is excellent. The choroid is the posterior portion of the middle layer of the eye. It is the eye’s vascular layer, and it contains many blood vessels that supply nutrients to the outer layers of the retina. The choroid also has a brown pigment that absorbs excess light rays that could interfere with vision. In the anterior part of this layer, the choroid creates the iris and the ciliary body. The iris is the colored portion of the eye. It is doughnut shaped, with the opening of the pupil in the center. The iris contains muscles that regulate the size of the pupil according to the intensity of the light; it becomes smaller in bright light and opens wider in dim light. The ciliary body contains both the ciliary muscle, which regulates the shape of the lens, and the ciliary processes, which secrete aqueous humor. The inner layer of the eye includes the retina in the posterior portion and the lens in the anterior portion. The rods and cones, optic nerve, optic disc, and fovea centralis are located in the retina. The delicate tissue of the retina is composed of light-sensitive neurons that convert light into neurological impulses. These impulses travel by means of the optic nerve to the brain, where they are converted into a visual form. Any damage to the retina has the potential to cause partial or complete blindness, because the neurological center of vision is located in the retina. The lens is a transparent, biconvex body that helps focus light after it passes through the cornea. The lens and the ciliary body divide the eye into two cavities. The posterior cavity, which is between the lens and the retina, contains the transparent, gel-like vitreous humor. Vitreous humor maintains the shape of the posterior eyeball. The anterior cavity, between the cornea and the lens, is filled with aqueous humor, which is continuously produced by the ciliary processes. Aqueous humor helps maintain normal pressure within the eye and provides nutrients to the lens and the cornea (Figure 37-1). Vision requires light and depends on the proper functioning of all parts of the eye (Table 37-1). A visual impulse begins with the passage of light through the cornea, where the light is refracted; it then passes through the aqueous humor and the pupil into the lens. The ciliary muscle adjusts the curvature of the lens to again refract the light rays so that they pass into the retina, triggering the photoreceptor cells of the rods and cones. At this point, the light energy is converted into an electrical impulse, which is sent through the optic nerve to the visual cortex of the occipital lobe of the brain; there, the light impulse is interpreted and a picture is created. TABLE 37-1 Functions of the Major Parts of the Eye Modified from Damjanov I: Pathology for the health-related professions, Philadelphia, 1996, Saunders. Four major types of refractive errors result when the eye is unable to focus light effectively on the retina. Refraction is the ability of the lens of the eye to bend parallel light rays coming into the eye so that the rays are focused simultaneously on the retina. An error of refraction means that the light rays are not refracted or bent properly and consequently do not focus correctly on the retina. Defects in the shape of the eyeball can cause a refractive error. Most refractive errors can be corrected with corrective lenses (Figure 37-2). When light enters the eye and focuses behind the retina, a person has hyperopia. This disorder occurs when the eyeball is too short from the anterior to the posterior wall. An individual with hyperopia has difficulty seeing objects that are close, at reading or working level. A convex corrective lens helps the eye’s internal lens place objects directly on the retina and creates a sharp, detailed image, or refractive surgery may be done to correct the shape of the lens. Myopia occurs when light rays entering the eye focus in front of the retina, causing objects at a distance to appear blurry and dull. Objects viewed at reading or working level are seen clearly. In this disorder, the eyeball is elongated from the anterior to the posterior wall, and the image cannot be sharpened by the internal lens of the eye. A concave corrective lens is used to focus the light rays on the retina, or surgery can be done to change the shape of the lens. However, the surgery is performed only on adults who have had a stable eye prescription for at least 1 year. As people age, the lens of the eye becomes less flexible, and the ciliary muscles weaken; consequently, changing the point of focus from distance to near becomes difficult; this is called presbyopia. The condition results in difficulty seeing at reading level. A combination corrective lens, known as a bifocal lens or a progressive lens correction, is used to focus both distal and proximal objects directly on the retina. Presbyopia actually starts at approximately age 10, but most people do not report an alteration in vision until their early forties. Conductive keratoplasty is the new laser procedure used to treat presbyopia. Astigmatism occurs when light rays entering the eye are focused irregularly. This usually occurs because the cornea or the lens is not a smooth sphere, but rather has an irregular shape. Ophthalmologists describe the lens as being shaped like a football rather than a sphere, such as a basketball. This causes light rays to be unevenly or diffusely focused on the retina, resulting in blurred vision. It is like attempting to focus on objects seen through a wavy piece of window glass. Astigmatism can be corrected with glasses, contacts, or surgery. Surgical correction attempts to reshape the cornea into a more spherical or uniformly curved surface. Refractive errors in vision can lead to squinting, frequent rubbing of the eyes, and headaches. The individual notices blurred vision or fading of words at reading level, or both. Some refractive errors are familial in nature. Eyeglasses and contact lenses are the traditional treatments for visual acuity problems caused by refractive errors. However, problems with the shape of the lens can be corrected surgically. Surgery is performed on an outpatient basis and requires only a short stay in the facility. Medical assistants employed in an outpatient eye surgery facility must be trained to fulfill this specialized role. Strabismus is failure of the eyes to track together, which means that both eyes do not look in the same direction at the same time. Adults can develop strabismus because of a condition or disease elsewhere in the body, such as diabetes mellitus, muscular dystrophy, or hypertension, or as the result of a head injury. In children, strabismus is caused by weakness in the muscles that control eye movement. If the condition appears in infancy or childhood, it is most commonly associated with amblyopia. Amblyopia often is correctable until approximately age 7 or until the retina is fully developed. Treatment involves having the child wear a patch over the unaffected eye so that the muscles of the “lazy” eye are strengthened. The main symptom in all age groups is diplopia (double vision). A constant, involuntary movement of one or both eyes is called nystagmus. The eye can move in any direction and the movement is accompanied by blurred vision. A child may be born with the problem (congenital nystagmus), or the condition may be acquired as a result of a brain tumor, an inner ear lesion, multiple sclerosis, or substance abuse. Nystagmus is caused by an abnormal function in the part of the brain that controls eye movements. Congenital nystagmus is more common than acquired nystagmus, is usually milder, does not worsen over time, and is not associated with any other disorder. A patient with signs and symptoms of nystagmus first should undergo neurological evaluation to determine the cause of the disorder, with treatment based on those findings. However, congenital nystagmus has no cure. Affected individuals typically are not aware of the eye movements, but they may have a decrease in visual acuity that can be corrected with surgery or corrective lenses. Many acute disorders of the eye are seen in the ophthalmologist’s office. These include the following: The cornea, the transparent outer covering of the eye, is prone to abrasion because of its location. Symptoms of corneal abrasion include pain, inflammation, tearing, and photophobia. The abrasion usually is caused by a foreign body in the eye or by direct trauma, such as from poorly fitting or dirty contact lenses. A corneal ulcer may form and become infected. Diagnosis is based on the patient’s signs and symptoms, but it can be confirmed with the instillation of fluorescein stain (Figure 37-3). After instillation of the stain, the physician uses a cobalt blue filtered light to visualize the abrasions, which appear green (Figure 37-4). If the abrasions are caused by a foreign body, it must be removed first; the eye then can be treated with antibiotic ophthalmic ointment to prevent infection. Although patching the affected eye has been recommended in the past, studies now show that patching does not reduce the patient’s pain and may actually prolong healing time. Corneal abrasions are quite painful, so the patient may be prescribed topical nonsteroidal antiinflammatory ophthalmic ointments (ung), such as diclofenac (Voltaren) and ketorolac (Acular), as well as oral analgesics. Most corneal abrasions heal in 24 to 72 hours, but the patient should be aware that symptoms can worsen if the affected eye is exposed to bright light, if excessive blinking occurs, or if the patient rubs the injured surface of the cornea against the inside of the eyelid. Because the patient may develop a secondary infection from the corneal injury, topical antibiotics, including bacitracin, erythromycin, or gentamicin ointments, may be prescribed. Patients with contact lenses may be prescribed oral antibiotics and should not wear their contacts until the abrasion has healed and the course of antibiotics has been completed. A cataract is a cloudy or opaque area in the normally clear lens of the eye that blocks the passage of light into the retina, causing impaired vision. This condition may result from injury to the eye, exposure to extreme heat or radiation, or inherited factors. However, most cataracts develop slowly and progressively as a result of the natural aging deterioration of the lens of the eye and typically occur after age 60. With advanced cataracts, the pupil of the eye appears white or gray. Blurred and dimmed vision is the initial symptom of a cataract. The patient may need a brighter reading light or must hold objects closer to the eyes for better viewing. Continued clouding of the lens may cause diplopia. The patient also needs frequent changes of eyeglass prescriptions. Patients with cataracts report difficulty with night vision (nyctalopia), seeing halo images around lights, and increased sensitivity to glare. If left untreated, cataracts ultimately can lead to blindness. When the patient’s vision becomes distorted or appears to be deteriorating, the ophthalmologist performs a slit lamp procedure, in which he or she examines the structures at the front of the eye using a combination of a low-power microscope and a high-intensity light that shines into the eye as a slit beam. The only known effective treatment for a cataract is surgical removal of the lens. This is performed as an outpatient procedure in a clinic or hospital. After the eye has been anesthetized, the inner portions of the lens—the nucleus and the cortex—are removed. The physician may use an extracapsular extraction, in which the cataract is removed in one piece, or phacoemulsification, in which an ultrasonic probe is used to break up the cataract and the pieces are aspirated, before an artificial intraocular lens (IOL) is implanted. The incision may be closed with fine sutures, or it may be sutureless and self-sealing. The procedure usually takes 15 minutes, and the patient typically can leave the facility after 1 hour. Patients should be aware that they will not be able to drive until cleared by the ophthalmologist, and that they may need help at home until their vision is clear. The patient is seen in the office the day after surgery and as frequently as needed for the next month. Vision gradually improves until it stabilizes, usually within 2 to 6 weeks; the patient then is fitted with new corrective lenses to match the improved vision. One of the most common and serious ocular disorders is a group of diseases known as glaucoma. Glaucoma is characterized by increased intraocular pressure (IOP), which damages the optic nerve and causes blindness if left untreated. It rarely occurs in people younger than age 40 and usually is seen in individuals older than age 60. The cause is unknown, but a hereditary tendency toward development of the most common forms has been noted. Glaucoma is responsible for approximately 12% of all cases of blindness. It is the leading cause of blindness among African-Americans, and it strikes approximately 2% of all individuals older than age 40 and 8% of those older than age 70 in the United States. The ciliary body constantly produces aqueous humor, which should circulate freely between the anterior and posterior chambers of the eye and eventually empty into the general circulation. A healthy eye is filled with fluid in an amount carefully regulated to maintain the shape of the eyeball. In chronic open-angle glaucoma, the channels that drain the fluid malfunction, and over time aqueous humor builds up, resulting in increased pressure, which affects the blood supply to the retina and the optic nerve. With acute closed-angle glaucoma, the opening of the drainage system narrows or closes completely, causing a sudden increase in IOP (Figure 37-5). Patients can have chronic open-angle glaucoma for a long time before symptoms occur. Early detection through regular ophthalmic examinations that include IOP measurements is crucial to prevent permanent vision loss. The need to change eyeglass prescriptions frequently, loss of peripheral vision, mild headaches, and impaired adaptation to the dark are some of the signs and symptoms that may be seen with chronic glaucoma. Acute closed-angle glaucoma has more obvious symptoms; the patient complains of severe pain, headaches, inflammation, photophobia, and seeing halos around lights. If left untreated, acute glaucoma can cause permanent blindness in a matter of days. Screening for glaucoma is conducted during a complete eye examination. The ophthalmologist first uses a tonometer with a slit lamp to measure IOP. The air puff tonometer records the degree of indentation of the cornea from a puff of pressurized air without touching the eye. An applanation tonometer records the pressure needed to indent the cornea when the instrument is applied to the front surface of the eye. Electronic tonometry is the most recently developed technique. The ophthalmologist gently places the rounded tip of a tool that looks like a pen directly on the cornea, with results evident on a small computer panel. Gonioscopy also can be used to examine the aqueous fluid drainage system and to determine whether the glaucoma is the open- or closed-angle type. In addition, an ophthalmoscopic examination can identify cupping of the optic disk, which indicates atrophy of the optic nerve. Open-angle glaucoma can be relieved with miotic and beta-blocker eye drops. The combinations of drugs used to treat glaucoma can vary considerably. Miotic medications increase the outflow of aqueous humor, and beta blockers reduce the production of aqueous humor (Table 37-2). It is imperative that the patient use prescribed eye drops and take oral medications daily to prevent further damage to the optic nerve. Laser surgery may be performed to create an opening or to build a new channel for drainage of the aqueous humor. The goal of treatment in any type of glaucoma is to diagnose the disease early and to effectively treat its progression, because any loss of sight that has occurred as the result of increased IOP cannot be regained. In closed-angle glaucoma, medications to lower IOP are prescribed so that surgery can be performed to create a channel in which aqueous fluid can circulate. This is a medical emergency, because the pressure must be relieved within a few hours or permanent vision damage occurs. TABLE 37-2 The macula lutea, the part of the retina near the optic nerve, defines the center of the field of vision. Macular degeneration is progressive deterioration of the macula lutea, which causes loss of central vision; the patient can see only the edges of the visual field. It affects more than 10 million Americans and is the leading cause of blindness in those older than 55. Two types of macular degeneration can occur. The dry form accounts for 90% of cases; it is painless and develops slowly, affecting sharp vision over time, so that reading and other activities that require fine detailed vision become impossible. Wet macular degeneration causes 90% of all severe vision losses from the disease and has a very acute onset and rapid progression. Dry macular degeneration is caused by the breakdown of light-sensitive cells in the region of the macula; the wet form is seen when new blood vessels behind the retina form and leak blood and fluid into the macula. The condition is age related, but additional risk factors include cigarette smoking, obesity, family history, cardiovascular disease, elevated blood cholesterol levels, light eye color, and excessive sun exposure. The disease has no known cure, but recent research indicates that antioxidants, including beta-carotene and vitamins C and E with zinc and copper, may prevent the condition or may slow its progress. A complete examination of the eye is technical and requires expensive equipment and the expertise of an ophthalmologist. However, a primary care physician performs some basic examinations and treatments of the eye. The ophthalmoscope is used to examine the interior of the eye. It projects a bright, narrow beam of light through the lens and illuminates the interior parts of the eye and retina. It is helpful for detecting disorders of the eyes and certain systemic disorders, such as diabetes mellitus. The eyelids are examined for edema, which may be the result of nephrosis, heart failure, allergy, or thyroid deficiency. Blepharoptosis, also called ptosis, is drooping of the upper eyelid that can be caused by a disorder of the third cranial nerve, muscular weakness as seen in muscular dystrophy, or myasthenia gravis. The pupils of the eyes are normally round and equal. Normal pupils constrict rapidly in response to light. This is demonstrated by shining a bright, pinpoint light into one eye from the side of the patient’s head. The pupil of an illuminated eye constricts, and the pupil of the other eye constricts equally. This test is called light and accommodation (L&A). An older patient’s eyes do not accommodate as well as those of a younger person. Each eye is checked this way. The patient then is asked to look at the physician’s finger as it is moved directly toward the patient’s nose to check for eye coordination. If the pupils are equal and round, respond normally to light, and adjust and focus on objects at different distances in a reasonable length of time, the physician charts the acronym PERRLA. Special techniques used in the ophthalmologist’s office include examinations performed with a slit lamp biomicroscope (Figure 37-6). This device is used to view fine details in the anterior segments of the eye. It may be used to view a foreign body, because it gives a well-illuminated and highly magnified view of the area. For this examination, the physician first orders administration of a mydriatic eye drop to dilate the pupil and enhance visualization of eye structures. A patient with exophthalmia (abnormal protrusion of the eye, possibly resulting from an overactive thyroid or a tumor behind the eyeball) is checked with an exophthalmometer. This instrument measures how far the eye protrudes beyond the edge of the eye socket and helps determine the level of tissue swelling and enlargement behind the eye. Distance visual acuity frequently is part of a complete physical examination (Procedure 37-1). It is widely used in schools and industry and is the best single test available for vision screening. Many cases of myopia, astigmatism, and hyperopia have been detected with this routine test. The chart most commonly used is the Snellen alphabetical chart (Figure 37-7, B). This chart displays various letters of the alphabet, which the patient must identify in ever smaller font sizes. Patients with limited knowledge of the English alphabet can be tested with the E chart. In addition, a chart that uses pictures as symbols is available. This chart is used for young children or individuals who do not know the alphabet. The symbol on the top line of the chart can be read at 200 feet by persons with normal vision. In each of the succeeding rows, from the top down, the size of the symbols is reduced so that a person with normal vision can see them at distances of 100, 70, 50, 40, 30, and 20 feet, consecutively.

Assisting in Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology

Learning Objectives

Vocabulary

Scenario

Examination of the Eye

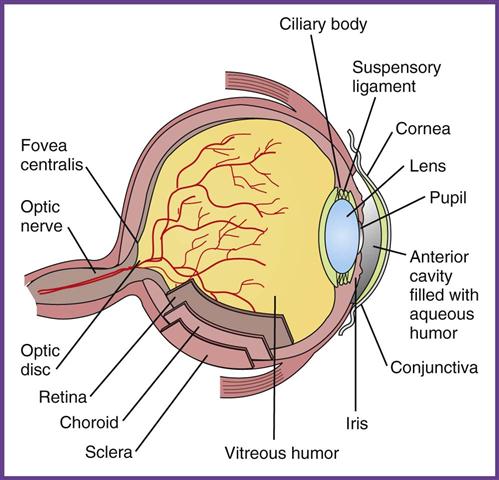

Anatomy and Physiology of the Eye

The Eyeball

Vision

STRUCTURE

FUNCTION

Sclera

External protection

Cornea

Light refraction

Choroid

Blood supply

Iris

Light absorption and regulation of pupil width

Ciliary body

Secretion of vitreous fluid; changes the shape of the lens

Lens

Light refraction

Retinal layer

Light receptor that transforms optic signals into nerve impulses

Rods

Distinguish light from dark and perceive shape and movement

Cones

Color vision

Central fovea

Area of sharpest vision

Macula lutea

Center of the retina; contains the fovea centralis, the area of most highly acute vision

External ocular muscles

Move the eyeball

Optic nerve

One of a pair of nerves that transmit visual stimuli to (cranial nerve II) the brain

Lacrimal glands

Produce tears

Eyelid

Protects eye

Disorders of the Eye

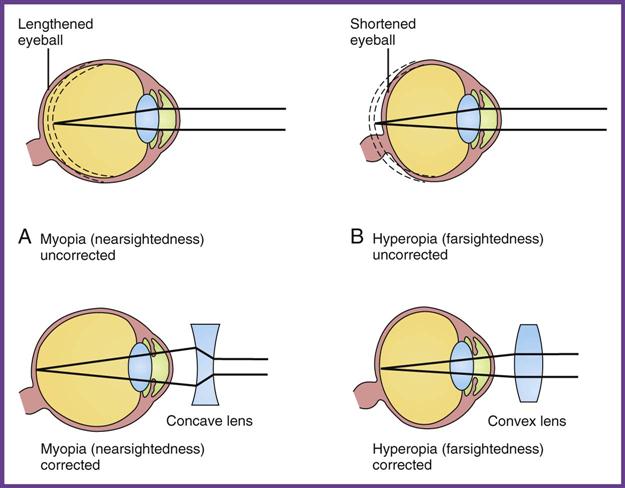

Refractive Errors

Hyperopia (Farsightedness).

Myopia (Nearsightedness).

Presbyopia.

Astigmatism.

Signs and Symptoms of Refractive Errors

Treatment of Refractive Errors

Strabismus

Nystagmus

Infections of the Eye

Disorders of the Eyeball

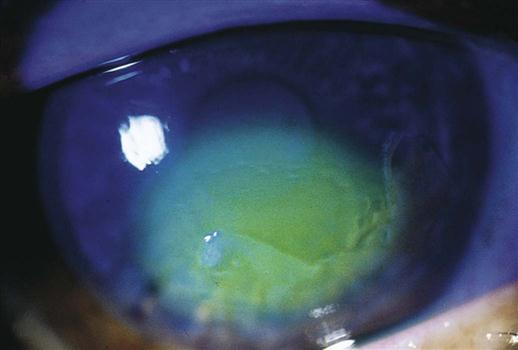

Corneal Abrasion

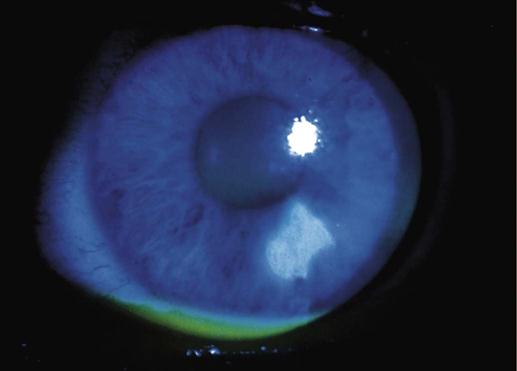

Cataract

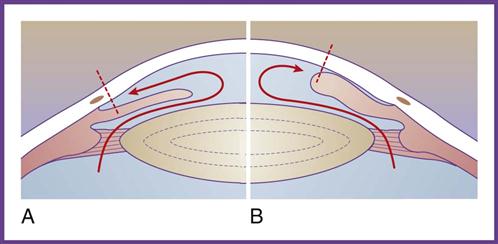

Glaucoma

DRUG NAME

CLASS AND USE

Neosporin ung

Antiinfective and steroid combination

Chloroptic, Ciloxan, erythromycin, and Garamycin ung

Topical antibiotic ointments

Viroptic

Antiinfective, antiviral

Pred-G, TobraDex

Antiinflammatory agents, corticosteroids

Ocufen, Acular, Voltaren

Topical antiinflammatory agents, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, analgesics

Isopto Atropine

Mydriatic eye drops; eye examinations

Betagan, Ocupress

Beta-blocker eye drops; glaucoma treatment

Alphagan

Alpha-adrenergic agonist eye drops; glaucoma treatment

Xalatan, Travatan, Lumigan

Prostaglandin analog eye drops; glaucoma treatment

Isopto Carpine, Pilocar

Miotic eye drops; glaucoma treatment

Macular Degeneration

Diagnostic Procedures

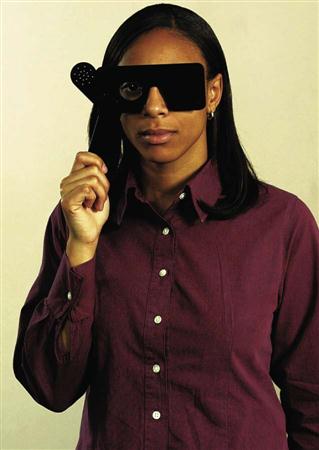

Distance Visual Acuity

Assisting in Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access