Donna D. Ignatavicius

Assessment of the Reproductive System

Learning Outcomes

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

4 Briefly review the anatomy and physiology of the male and the female reproductive systems.

5 Identify reproductive changes associated with aging and their implications for nursing care.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Lymphatic Drainage of the Breast

Animation: The Menstrual Cycle

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Video Clip: Bimanual Examination

Video Clip: External Genitalia

Video Clip: Inguinal Hernia Evaluation

Video Clip: Inspection (Standing)

Video Clip: Speculum Examination

The nurse is typically the first health care professional to assess the patient with a reproductive system health problem or hear a patient’s concern about a reproductive problem. These problems often affect the need for sexuality, both its physical and psychosocial aspects, and are difficult for many people to discuss. Assessment of the male and the female reproductive systems should be part of every complete physical assessment. Be aware of and sensitive to differences in sexual orientation and practices.

This chapter reviews the focused reproductive system assessment that a nurse generalist performs. An advanced practice nurse or other health care provider performs the comprehensive reproductive examination. A more detailed discussion of human sexuality is found in a fundamentals or basic nursing text.

Anatomy and Physiology Review

Structure and Function of the Female Reproductive System

The female reproductive system is located both outside (external) and inside (internal) the body.

External Genitalia

The external female genitalia, or vulva, extend from the mons pubis to the anal opening. The mons pubis is a fat pad that covers the symphysis pubis and protects it during coitus (sexual intercourse).

The labia majora are two vertical folds of adipose tissue that extend posteriorly from the mons pubis to the perineum. The size of the labia majora varies depending on the amount of fatty tissue present. The skin over the labia majora is usually darker than the surrounding skin and is highly vascular. It protects inner vulval structures and enhances sexual arousal.

The labia majora surround two thinner, vertical folds of reddish epithelium called the labia minora. The labia minora are highly vascular and have a rich nerve supply. Emotional or physical stimulation produces marked swelling and sensitivity. Numerous sebaceous glands in the labia minora lubricate the entrance to the vagina. The clitoris is a small, cylindric organ that is composed of erectile tissue with a high concentration of sensory nerve endings. During sexual arousal, the clitoris becomes larger and increases sexual sensation.

The vestibule is a longitudinal area between the labia minora, the clitoris, and the vagina that contains Bartholin glands and the openings of the urethra, Skene’s glands (paraurethral glands), and vagina. The two Bartholin glands, located deeply toward the back on both sides of the vaginal opening, secrete lubrication fluid during sexual excitement. Their ductal openings are usually not visible.

The area between the vaginal opening and the anus is the perineum. The skin of the perineum covers the muscles, fascia, and ligaments that support the pelvic structures.

Internal Genitalia

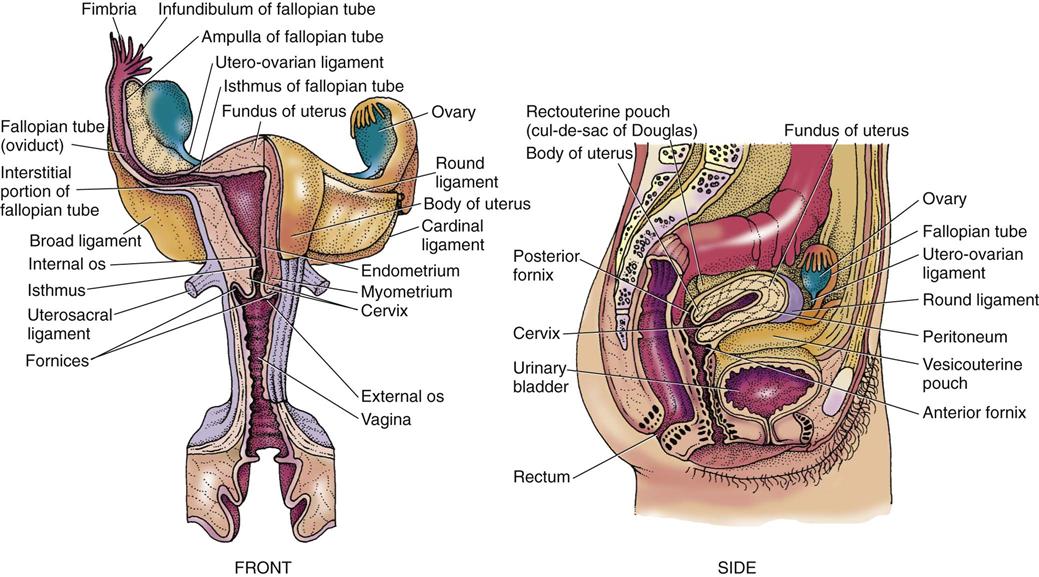

The internal female genitalia are shown in Fig. 72-1. The vagina is a hollow tube that extends from the vestibule to the uterus. In addition to being the channel for the passage of the menstrual flow, the vagina allows for insertion of the penis during intercourse and passage of the fetus during a vaginal birth. Reduced estrogen levels occurring during menopause cause the vaginal wall to become dry, thinner, and smoother. The vagina then atrophies and is prone to pathogenic growth, resulting in a variety of types of infections.

The amounts of glycogen and lubricating fluid secreted by the vaginal cells are influenced by ovarian hormones. The normal vaginal bacteria (flora) interact with the secretions to produce lactic acid and maintain an acidic pH (3.5 to 5) in the vagina. This acidity helps prevent infection in the vagina.

At the upper end of the vagina, the uterine cervix projects into a cup-shaped vault of thin vaginal tissue. The recessed pockets around the cervix permit palpation of the internal pelvic organs. The posterior area provides access into the peritoneal cavity for diagnostic or surgical purposes.

The uterus (or “womb”) is a thick-walled, muscular organ attached to the upper end of the vagina. This inverted pear–shaped organ is located within the true pelvis, between the bladder and the rectum. The uterus is made up of the body and the cervix.

The upper segment of the uterine body, between the insertion sites of the fallopian tubes, is referred to as the fundus. Although the uterus is a hollow organ, its walls are in such close proximity in the nonpregnant state that its cavity is merely a slit.

The cervix is a short (1 inch [2.5 cm]), narrowed portion of the uterus and extends into the vagina. The surface of the cervix and the canal are the sites for Papanicolaou (Pap) testing. (See discussion on p. 1581.)

The fallopian tubes (uterine tubes) insert into the fundus of the uterus and extend laterally close to the ovaries. They provide a duct between the ovaries and the uterus for the passage of ova and sperm. In most cases, the ovum is fertilized in these tubes.

The ovaries are a pair of almond-shaped organs located near the lateral walls of the upper pelvic cavity. After menopause, they become smaller. These small organs develop and release ova and produce the sex steroid hormones (estrogen, progesterone, androgen, and relaxin). Adequate amounts of these hormones are needed for normal female growth and development and to maintain a pregnancy.

Breasts

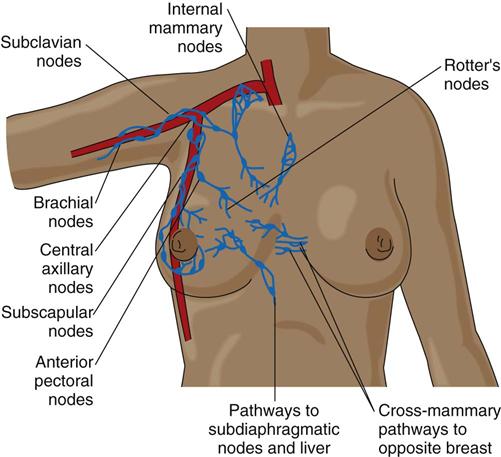

The female breasts are a pair of mammary glands that develop in response to secretions from the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and ovaries. The breasts are an accessory of the reproductive system that nourish the infant after birth.

Breast tissue is composed of a network of glandular and ductal tissue, fibrous tissue, and fat. The proportion of each component of breast tissue depends on genetic factors, nutrition, age, and obstetric history. The breasts are supported by ligaments that are attached to underlying muscles. They have abundant blood supply and lymph flow that drains from an extensive network toward the axilla (Fig. 72-2).

Structure and Function of the Male Reproductive System

The male reproductive system also consists of external and internal genitalia. The primary male hormone for sexual development and function is testosterone. Testosterone production is fairly constant in the adult male. Only a slight and gradual reduction of testosterone production occurs in the older adult male until he is in his 80s. Low testosterone levels decrease muscle mass, reduce skin elasticity, and lead to postural changes and changes in sexual performance.

The penis is an organ for urination and intercourse consisting of the body or shaft and the glans penis (the distal end of the penis). The glans is the smooth end of the penis and contains the slitlike opening of the urethral meatus. The urethra is the pathway for the exit of both urine and semen. A continuation of skin covers the glans and folds to form the prepuce (foreskin). Surgical removal of the foreskin (circumcision) for religious or cultural reasons is a common procedure in the United States and other Western countries.

The scrotum is a thin-walled, fibromuscular pouch that is behind the penis and suspended below the pubic bone. This pouch protects the testes, epididymis, and vas deferens in a space that is slightly cooler than inside the abdominal cavity.

The scrotal skin is darkly pigmented and contains sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and few hair follicles. It contracts with cold, exercise, tactile stimulation, and sexual excitement.

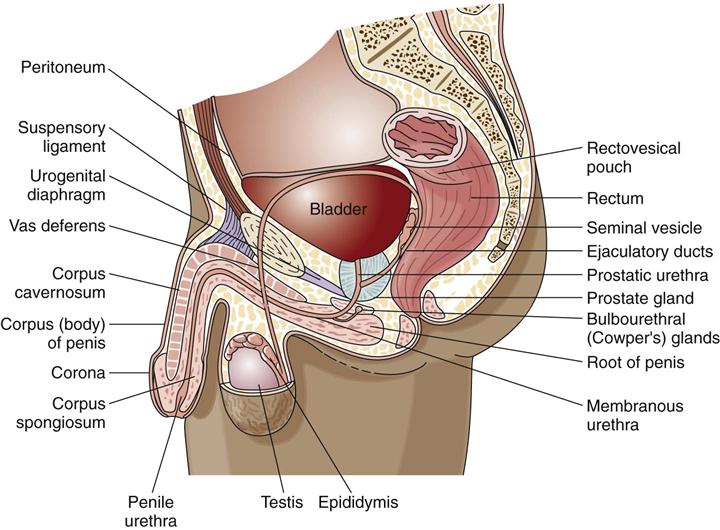

The internal male genitalia are shown in Fig. 72-3. The major organs are the testes and prostate gland. The testes are a pair of oval organs in the scrotum that produce sperm and testosterone. Each testis is suspended in the scrotum by the spermatic cord, which provides blood, lymphatic, and nerve supply to the testis. Sympathetic nerve fibers are located on the arteries in the cord, and sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers are on the vas deferens. When the testes are damaged, these autonomic nerve fibers transmit excruciating pain and a sensation of nausea.

The epididymis is the first portion of a ductal system that transports sperm from the testes to the urethra and is a site of sperm maturation. The vas deferens, or ductus deferens, is a firm, muscular tube that continues from the tail of each epididymis. The end of each vas deferens is a reservoir for sperm and tubular fluids. They merge with ducts from the seminal vesicle to form the ejaculatory ducts at the base of the prostate gland. Sperm from the vas deferens and secretions from the seminal vesicles move through the ejaculatory duct to mix with prostatic fluids in the prostatic urethra.

The prostate gland is a large accessory gland of the male reproductive system. It secretes a milky alkaline fluid that adds bulk to the semen, enhances sperm movement, and neutralizes acidic vaginal secretions. The prostate gland can be palpated through the rectum and should not project more than  inch (1 cm) into the rectal lumen.

inch (1 cm) into the rectal lumen.

As men age, the prostate gland becomes clinically significant. Men older than 50 years commonly have an enlarged prostate (benign prostatic hyperplasia [BPH]), which can cause problems such as overflow incontinence and nocturia (nighttime urination). Prostate function depends on adequate levels of testosterone.

The inguinal area (groin) is located between the superior iliac spine and the symphysis pubis and is the junction of the lower abdominal wall and thigh. The area is a common site for a hernia, which is a loop of bowel that protrudes through a weak spot in the muscles.

Reproductive Changes Associated with Aging

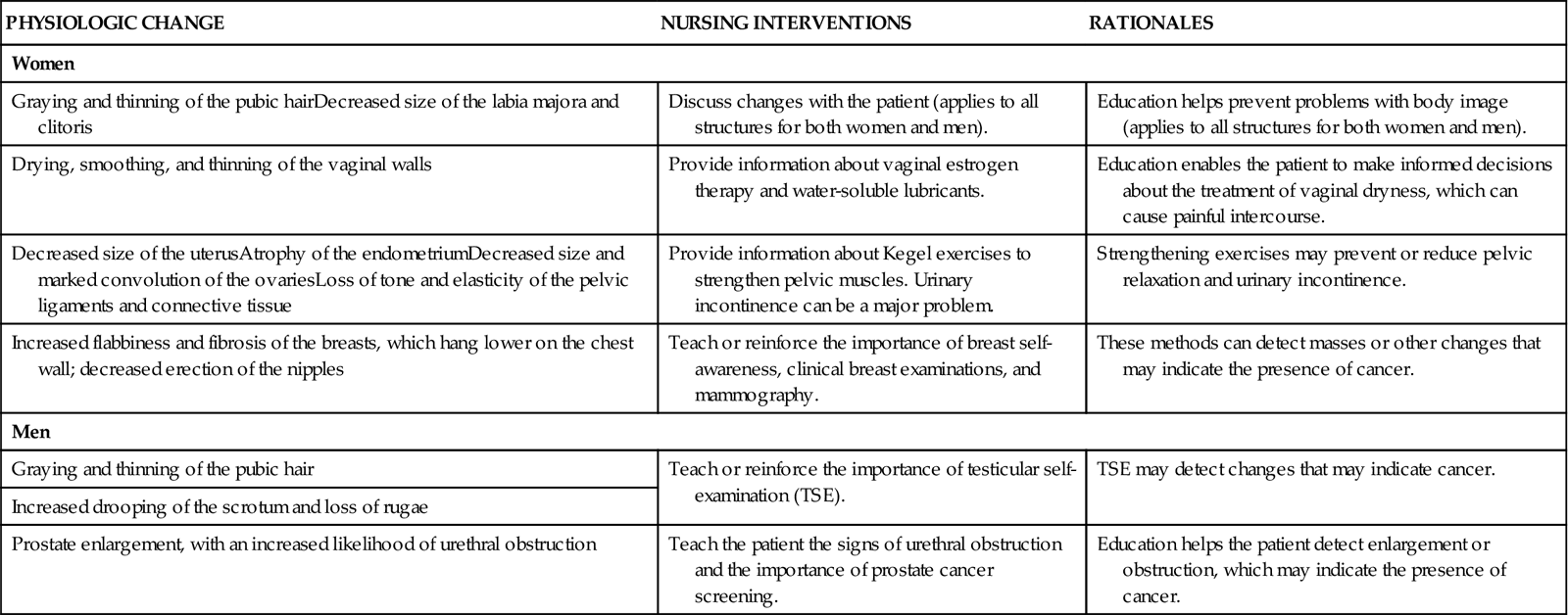

Age affects the function of both the male and the female reproductive systems. Many changes in the reproductive system occur as people age (Chart 72-1).

Assessment Methods

Patient History

Establish a trusting relationship with the patient. Many patients are hesitant to share their reproductive history or concerns about sexuality. Respect their choice to refuse to answer questions and talk about their reproductive problems or sexual practices. Chart 72-2 describes questions to consider when assessing the patient’s sexuality and reproductive health using Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns.

Assess the patient’s health habits, such as diet, sleep, and exercise patterns. Low levels of body fat may be related to ovarian dysfunction. Assess for alcohol, tobacco, and drug use (prescribed, over-the-counter [OTC], and illicit drugs), because libido (sex drive), sperm production, and the ability to have or sustain an erection can be affected by these substances.

Ask female patients about the date and result of their most recent Pap test, breast self-examination, and vulvar self-examination. Determine when male patients older than 50 years had their last prostate examination and prostate-specific antigen test.

Ask about childhood illnesses that could have an effect on the reproductive system. For example, mumps in men may cause orchitis (painful inflammation and swelling of the testes) and can lead to testicular atrophy and sterility.

Assess for any chronic illnesses or surgeries that could affect reproductive function. For instance, endocrine disorders may affect the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal function of men or women. Almost any disease that disturbs a woman’s metabolism or nutrition can depress ovarian function and cause amenorrhea (absence of menses). Failure of ovulation is associated with a greater risk for endometrial cancer. Patients with diabetes mellitus may experience physiologic changes such as vaginal dryness or impotence. Chronic disorders of the nervous system, respiratory system, or cardiovascular system can alter the sexual response.

Reproductive system dysfunction can also result from irradiation; prolonged use of corticosteroids, internal or external estrogen, or testosterone; and chemotherapy drugs. In addition, past severe infections can alter a person’s reproductive ability. For example, pelvic inflammatory disease or a ruptured appendix followed by peritonitis can cause strictures or adhesions in the fallopian tubes and pelvic scarring. Salpingitis (uterine tube infection) is usually caused by chlamydial infection and can result in female infertility. If a young woman began having intercourse at a very early age and/or has multiple sex partners, she is at high risk for cervical cancer. Breast cancer is more common in women who have not experienced childbearing. Ask about a history of infections or prolonged fever in males that may have damaged sperm production or caused obstruction of the seminal tract, because these changes cause infertility.

Data about sexual activity are important to obtain as part of the history. Heterosexual activity should not be assumed. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) issues are often not assessed by health care professionals or shared by the patient. Table 4-3 in Chapter 4 suggests sensitive ways to ask questions about sexual activity.

Nutrition History

A nutrition history is often critical for an accurate assessment of reproductive system problems. For example, fatigue and low libido may occur with poor diet and anemia. Obesity raises the risk for uterine cancer. High-fat diets may increase the risk for cancer of the breast, ovary, and prostate gland (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2010). Ask the patient to recall his or her dietary intake for a recent 24-hour period to assess quality.

Assess the patient’s height, weight, and body mass index. The patient may be hesitant to discuss practices such as bingeing, purging, anorexic behaviors, or excessive exercise. However, these practices may affect the reproductive system. A certain level of body fat and weight is necessary for the onset of menses and the maintenance of regular menstrual cycles. Decreased body fat results in insufficient estrogen levels.

Women have special nutrition needs. Those who use oral contraceptives need increased sources of folic acid and vitamins B6, B12, and C. Heavy menstrual bleeding, particularly in women who have intrauterine devices, may require oral iron supplements. Teach all women of any age about their body’s need for calcium. Although adequate calcium intake throughout life is needed, it is especially important during and after menopause to help prevent osteoporosis due to decreased estrogen production (see Chapter 53).

Family History and Genetic Risk

The family history helps determine the patient’s risk for conditions that affect reproductive functioning. A delayed or early development of secondary sex characteristics may be a familial pattern.

The current age and health status of family members are important. Evidence of medical diseases or reproductive problems in family members (e.g., diabetes, endometriosis, reproductive cancer) allows better interpretation of the patient’s current symptoms. For example, daughters of women who were given diethylstilbestrol (DES) to control bleeding during pregnancy are at increased risk for infertility and reproductive tract cancer.

Specific BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutations increase the overall risk for breast or ovarian cancer (ACS, 2010). Men with first-degree relatives (e.g., father, brother) with prostate cancer are at greater risk for the disease than men in the general population. Testicular cancer can also be familial (ACS, 2010). More information about genetic risks is discussed with specific health problems in later chapters of this unit.

Current Health Problems

Most patients seek medical attention as a result of pain, bleeding, discharge, and masses (Chart 72-3). Pain related to reproductive system disorders may be confused with or cause signs and symptoms that are usually associated with GI or urinary health problems (e.g., urinary frequency). Ask the patient to describe the nature of the pain, including its type, intensity, timing and location, duration, and relationship to menstrual, sexual, urinary, or GI function. Assess the factors that exacerbate (worsen) or relieve the pain. Ask about sleeping patterns and if pain or other manifestation is affecting the ability to get adequate rest (Ruhl, 2010).