Donna D. Ignatavicius

Assessment of the Musculoskeletal System

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

5 Recall the anatomy and physiology of the musculoskeletal system.

6 Conduct a musculoskeletal history using Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns.

7 Assess patients for mobility, gait, motor skills, pain, and the use of assistive devices.

8 Interpret assessment findings in a patient with a musculoskeletal health problem.

9 Assess patients regarding iodine allergy before imaging assessments.

10 Explain the use of laboratory testing for a patient with a musculoskeletal health problem.

11 Develop a teaching plan to educate the patient and family about diagnostic procedures.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Classification of Joints: Condyloid Joint

Animation: Classification of Joints: Gliding Joint (Hand)

Animation: Classification of Joints: Hinge Joint

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges

Audio Glossary

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Video Clip: Gait

Video Clip: Muscular Development and Strength

The musculoskeletal system is the second largest body system. It includes the bones, joints, and skeletal muscles, as well as the supporting structures needed to move them. Mobility (movement) is a basic human need that is essential for performing ADLs. When a patient cannot move to perform ADLs or other daily routines, self-esteem and a sense of self-worth can be diminished.

Disease, surgery, and trauma can affect one or more parts of the musculoskeletal system, often leading to decreased mobility. When mobility is impaired for a long time, other body systems can be affected. For example, prolonged immobility can lead to skin breakdown, constipation, and thrombus formation. If nerves are damaged by trauma or disease, patients may also have problems with sensation.

Anatomy and Physiology Review

Skeletal System

The skeletal system consists of 206 bones and multiple joints. The growth and development of these structures occur during childhood and adolescence and are not discussed in this text. Common physical skeletal differences among ethnic groups are listed in Table 52-1.

TABLE 52-1

MUSCULOSKELETAL DIFFERENCES IN SELECTED GROUPS

| GROUP | MUSCULOSKELETAL DIFFERENCES |

| African Americans | Greater bone density than Europeans, Asians, and Hispanics. Accounts for decreased incidence of osteoporosis. |

| Amish | Greater incidence of dwarfism than in other populations. |

| Chinese Americans | Bones are shorter and smaller with less bone density. Increased incidence of osteoporosis. |

| Egyptian Americans | Shorter in stature than Euro-Americans and African Americans. |

| Filipino/Vietnamese | Short in stature; adult height about 5 feet. |

| Irish Americans | Taller and broader than other Euro-Americans. Less bone density than African Americans. |

| Navajo American Indians | Taller and thinner than other American Indians. |

Bones

Types and Structure.

Bone can be classified in two ways—by shape and by structure. Long bones, such as the femur, are cylindric with rounded ends and often bear weight. Short bones, such as the phalanges, are small and bear little or no weight. Flat bones, such as the scapula, protect vital organs and often contain blood-forming cells. Bones that have unique shapes are known as irregular bones. The carpal bones in the wrist and the small bones in the inner ear are examples of irregular bones. The sesamoid bone is the least common type and develops within a tendon; the patella is a typical example.

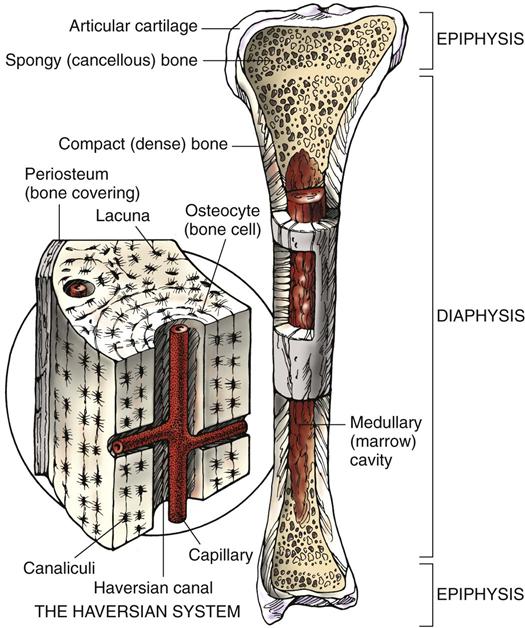

The second way bone is classified is by structure or composition. As shown in Fig. 52-1, the outer layer of bone, or cortex, is composed of dense, compact bone tissue. The inner layer, in the medulla, contains spongy, cancellous tissue. Almost every bone has both tissue types but in varying quantities. The long bone typically has a shaft, or diaphysis, and two knoblike ends, or epiphyses.

The structural unit of the cortical compact bone is the haversian system, which is detailed in Fig. 52-1. The haversian system is a complex canal network containing microscopic blood vessels that supply nutrients and oxygen to bone, as well as lacunae, which are small cavities that house osteocytes (bone cells). The canals run vertically within the hard cortical bone tissue.

The softer cancellous tissue contains large spaces, or trabeculae, which are filled with red and yellow marrow. Hematopoiesis (production of blood cells) occurs in the red marrow. The yellow marrow contains fat cells, which can be dislodged and enter the bloodstream to cause fat embolism syndrome (FES), a life-threatening complication. Volkmann’s canals connect bone marrow vessels with the haversian system and periosteum, the outermost covering of the bone. In the deepest layer of the periosteum are osteogenic cells, which later differentiate into osteoblasts (bone-forming cells) and osteoclasts (bone-destroying cells).

Bone also contains a matrix, or osteoid, consisting chiefly of collagen, mucopolysaccharides, and lipids. Deposits of inorganic calcium salts (carbonate and phosphate) in the matrix provide the hardness of bone.

Bone is a very vascular tissue. Its estimated total blood flow is between 200 and 400 mL/min. Each bone has a main nutrient artery, which enters near the middle of the shaft and branches into ascending and descending vessels. These vessels supply the cortex, the marrow, and the haversian system. Very few nerve fibers are connected to bone. Sympathetic nerve fibers control dilation of blood vessels. Sensory nerve fibers transmit pain signals experienced by patients who have primary lesions of the bone, like bone tumors.

Function.

• Provides a framework for the body and allows the body to be weight bearing, or upright

• Supports the surrounding tissues (e.g., muscle and tendons)

• Assists in movement through muscle attachment and joint formation

• Protects vital organs, such as the heart and lungs

• Manufactures blood cells in red bone marrow

• Provides storage for mineral salts (e.g., calcium and phosphorus)

After puberty, bone reaches its maturity and maximum growth. Bone is a dynamic tissue. It undergoes a continuous process of formation and resorption, or destruction, at equal rates until the age of 35 years. In later years, bone resorption increases, decreasing bone mass and predisposing patients to injury, especially older women.

Numerous minerals and hormones affect bone growth and metabolism, including:

Bone accounts for about 99% of the calcium in the body and 90% of the phosphorus. In healthy adults, the serum concentrations of calcium and phosphorus maintain an inverse relationship. As calcium levels rise, phosphorus levels decrease. When serum levels are altered, calcitonin and PTH work to maintain equilibrium. If the calcium in the blood is decreased, the bone, which stores calcium, releases calcium into the bloodstream in response to PTH stimulation.

Calcitonin is produced by the thyroid gland and decreases the serum calcium concentration if it is increased above its normal level. Calcitonin inhibits bone resorption and increases renal excretion of calcium and phosphorus as needed to maintain balance in the body.

Vitamin D and its metabolites are produced in the body and transported in the blood to promote the absorption of calcium and phosphorus from the small intestine. They also seem to enhance PTH activity to release calcium from the bone. A decrease in the body’s vitamin D level can result in osteomalacia (softening of bone) in the adult. Vitamin D metabolism and osteomalacia are described in Chapter 53.

When serum calcium levels are lowered, parathyroid hormone (PTH, or parathormone) secretion increases and stimulates bone to promote osteoclastic activity and release calcium to the blood. PTH reduces the renal excretion of calcium and facilitates its absorption from the intestine. If serum calcium levels increase, PTH secretion diminishes to preserve the bone calcium supply. This process is an example of the feedback loop system of the endocrine system.

Growth hormone secreted by the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland is responsible for increasing bone length and determining the amount of bone matrix formed before puberty. During childhood, an increased secretion results in gigantism and a decreased secretion results in dwarfism. In the adult, an increase causes acromegaly, which is characterized by bone and soft-tissue deformities (see Chapter 65).

Adrenal glucocorticoids regulate protein metabolism, either increasing or decreasing catabolism to reduce or intensify the organic matrix of bone. They also aid in regulating intestinal calcium and phosphorus absorption.

Estrogens stimulate osteoblastic (bone-building) activity and inhibit PTH. When estrogen levels decline at menopause, women are susceptible to low serum calcium levels with increased bone loss (osteoporosis). Androgens, such as testosterone in men, promote anabolism (body tissue building) and increase bone mass.

Thyroxine is one of the principal hormones secreted by the thyroid gland. Its primary function is to increase the rate of protein synthesis in all types of tissue, including bone. Insulin works together with growth hormone to build and maintain healthy bone tissue.

Joints

A joint is a space in which two or more bones come together. This is also referred to as articulation of the joint. The major function of a joint is to provide movement and flexibility in the body.

There are three types of joints in the body:

• Synarthrodial, or completely immovable, joints (e.g., in the cranium)

• Amphiarthrodial, or slightly movable, joints (e.g., in the pelvis)

• Diarthrodial (synovial), or freely movable, joints (e.g., the elbow and knee)

Although any of these joints can be affected by disease or injury, the synovial joints are most commonly involved.

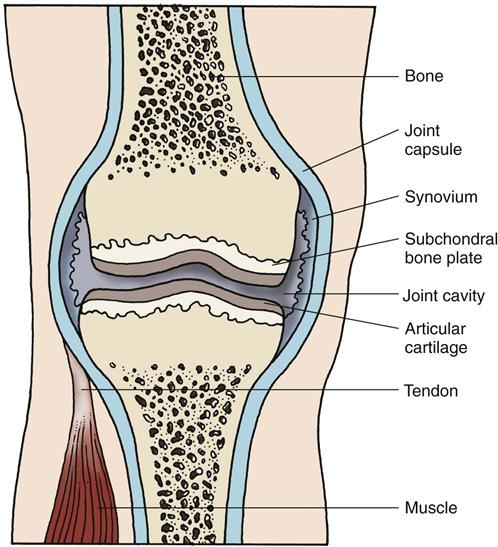

The diarthrodial, or synovial, joint is the most common type of joint in the body. Synovial joints are the only type lined with synovium, a membrane that secretes synovial fluid for lubrication and shock absorption. As shown in Fig. 52-2, the synovium lines the internal portion of the joint capsule but does not normally extend onto the surface of the cartilage at the spongy bone ends. Articular cartilage consists of a collagen fiber matrix impregnated with a complex ground substance. Patients with inflammatory types of arthritis often have synovitis (synovial inflammation) and breakdown of the cartilage. Bursae, small sacs lined with synovial membrane, are located at joints and bony prominences to prevent friction between bone and structures adjacent to bone. These structures can also become inflamed, causing bursitis.

Synovial joints are described by their anatomic structures. Ball-and-socket joints (shoulder, hip) permit movement in any direction. Hinge joints (elbow) allow motion in one plane—flexion and extension. The knee is often classified as a hinge joint, but it rotates slightly, as well as flexes and extends. It is best described as a condylar type of synovial joint. The gliding movement of the wrist is characteristic of the biaxial joint. Pivot joints permit rotation only, as in the radioulnar area.

Muscular System

There are three types of muscle in the body: smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, and skeletal muscle. Smooth, or non-striated, involuntary muscle is responsible for contractions of organs and blood vessels and is controlled by the autonomic nervous system. Cardiac muscle, or striated, involuntary muscle, is also controlled by the autonomic nervous system. The smooth and cardiac muscles are discussed with the body systems to which they belong in the assessment chapters.

In contrast to smooth and cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle is striated, voluntary muscle controlled by the central and peripheral nervous systems. The junction of a peripheral motor nerve and the muscle cells that it supplies is sometimes referred to as a motor end plate. Muscle fibers are held in place by connective tissue in bundles, or fasciculi. The entire muscle is surrounded by dense fibrous tissue, or fascia, which contains the muscle’s blood, lymph, and nerve supply.

The main function of skeletal muscle is movement of the body and its parts. When bones, joints, and supporting structures are adversely affected by injury or disease, the adjacent muscle tissue is often involved, limiting mobility. During the aging process, muscle fibers decrease in size and number, even in well-conditioned adults. Atrophy results when muscles are not regularly exercised and they deteriorate from disuse.

Supporting structures for the muscular system are very susceptible to injury. They include tendons (bands of tough, fibrous tissue that attach muscles to bones) and ligaments, which attach bones to other bones at joints.

Musculoskeletal Changes Associated with Aging

Osteopenia, or decreased bone density (bone loss), occurs as one ages. Many older adults, especially white, thin women, have severe osteopenia, a disease called osteoporosis. This condition causes postural and gait changes and predisposes the person to fractures. Chapter 53 discusses this health problem in detail.

Synovial joint cartilage can become less elastic and compressible as a person ages. As a result of these cartilage changes and continued use of joints, the joint cartilage becomes damaged, leading to osteoarthritis (OA). Genetic defects in cartilage may also contribute to joint disease. The most common joints affected are the weight-bearing joints of the hip, knee, and cervical and lumbar spine, but joints in the shoulder and upper extremity, feet, and hands can be affected. Refer to Chapter 20 for a complete discussion of OA.

As one ages, muscle tissue atrophies. Increased activity and exercise can slow the progression of atrophy and restore muscle strength. Musculoskeletal changes cause decreased coordination, loss of muscle strength, gait changes, and a risk for falls with injury. (See Chapter 3 for discussion on fall prevention.) Chart 52-1 lists the major anatomic and physiologic changes and implications for nursing care.

Assessment Methods

Patient History

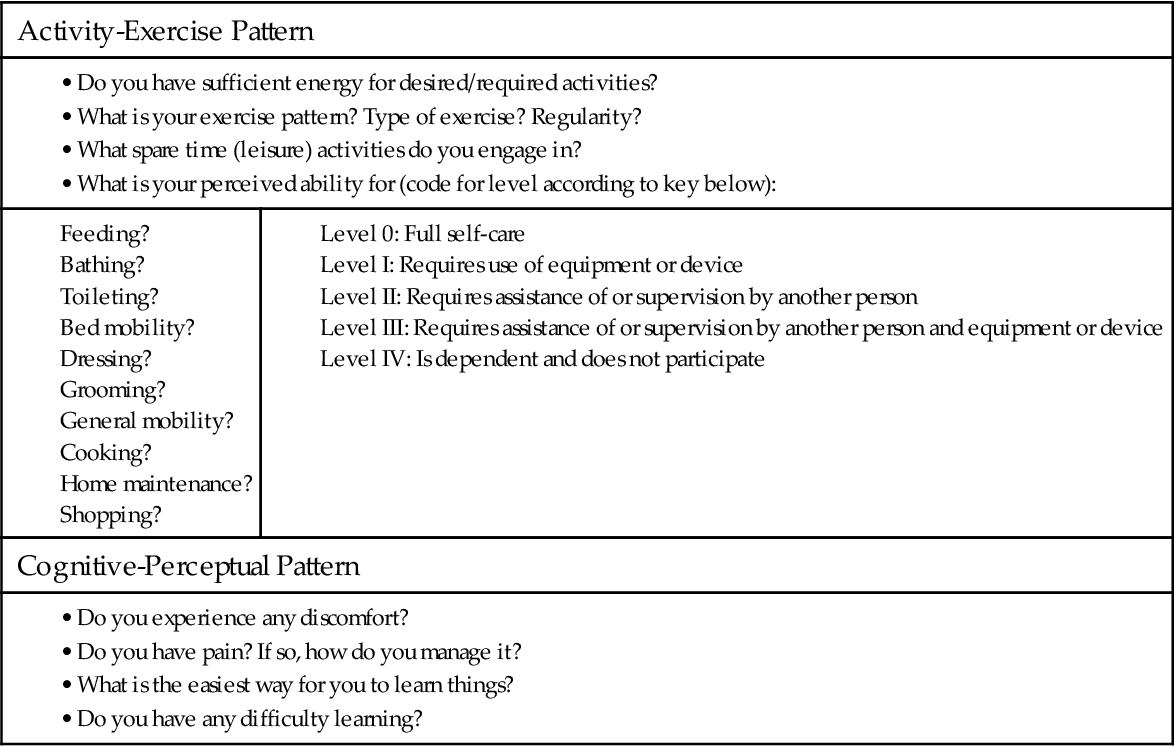

In the assessment of a patient with an actual or potential musculoskeletal problem, a detailed and accurate history is helpful in identifying priority problems and nursing interventions (Chart 52-2). The history reveals information about the patient that can direct the physical assessment.

Accidents, illnesses, lifestyle, and drugs may contribute to a patient’s current problem. Young men are at the greatest risk for trauma related to motor vehicle crashes. Older adults are at the greatest risk for falls that result in fractures and soft-tissue injury. When taking a personal health history, question the patient about any traumatic injuries and sports activities, no matter when they occurred. An injury to the lumbar spine 30 years ago may have caused a patient’s current low back pain. A motor vehicle crash or sports injury can cause osteoarthritis years after the event.

Previous or current illness or disease may affect musculoskeletal status. For example, a patient with diabetes who is treated for a foot ulcer is at high risk for acute or chronic osteomyelitis (bone infection). In addition, diabetes slows the healing process. Ask the patient about any previous hospitalizations and illnesses or complications. Inquire about his or her ability to perform ADLs independently or if assistive/adaptive devices are used.

Current lifestyle also contributes to musculoskeletal health. Weight-bearing activities such as walking can reduce risk factors for osteoporosis and maintain muscle strength. High-impact sports, such as excessive jogging or running, can cause musculoskeletal injury to soft tissues and bone. Tobacco use slows the healing of musculoskeletal injuries. Excessive alcohol intake can decrease vitamins and nutrients the person needs for bone and muscle tissue growth.

When assessing a patient with a possible musculoskeletal alteration, inquire about occupation or work life. A person’s occupation can cause or contribute to an injury. For instance, fractures are not uncommon in patients whose jobs require manual labor, such as housekeepers, mechanics, and industrial workers. Certain occupations, such as computer-related jobs, may predispose a person to carpal tunnel syndrome (entrapment of the median nerve in the wrist) or neck pain. Construction workers and health care workers may experience back injury from prolonged standing and excessive lifting. Amateur and professional athletes often experience acute musculoskeletal injuries (e.g., joint dislocations and fractures) and chronic disorders (e.g., joint cartilage trauma), which can lead to osteoarthritis.

Ask about allergies, particularly allergy to dairy products, and previous and current use of drugs—prescribed, over-the-counter, and illicit. Allergy to dairy products could cause decreased calcium intake. Some drugs, such as steroids, can negatively affect calcium metabolism and promote bone loss. Other drugs may be taken to relieve musculoskeletal pain. Inquire about herbs, vitamin and mineral supplements, or biologic compounds that may be used for arthritis and other musculoskeletal problems, such as glucosamine and chondroitin. Complementary and alternative therapies are commonly used by patients with various types of arthritis and arthralgias (joint aching).

Nutrition History

A brief review of the patient’s nutrition history helps determine any risks for inadequate nutrient intake. For example, most people, especially women, do not get enough calcium in their diet. Determine if the patient has had a significant weight gain or loss.

Ask the patient to recall a typical day of food intake to help identify deficiencies and excesses in the diet. Lactose intolerance is a common problem that can cause inadequate calcium intake. People who cannot afford to buy food are especially at risk for undernutrition. Some older adults and others are not financially able to buy the proper foods for adequate nutrition.

Inadequate protein or insufficient vitamin C or D in the diet slows bone and tissue healing. Obesity places excess stress and strain on bones and joints, with resulting fractures and trauma to joint cartilage. In addition, obesity inhibits mobility in patients with musculoskeletal problems, which predisposes them to complications such as respiratory and circulatory problems. People with eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are also at risk for osteoporosis related to decreased intake of calcium and vitamin D.

Family History and Genetic Risk

Obtaining a family history assists in identifying disorders that have a familial or genetic tendency. Osteoporosis (age-related bone loss) and gout, for instance, often occur in several generations of a family. Osteogenic sarcoma, a type of bone cancer, may be genetically influenced by Tp53 gene mutation (Nussbaum et al., 2007). Positive family history of these types of disorders can increase risks to the patient. Chapters 20 and 53 provide a more complete description of musculoskeletal problems that have strong genetic links.

Current Health Problems

The most common reports of persons with a musculoskeletal problem are pain and weakness, either of which can impair mobility. Collect data pertinent to the patient’s presenting health problem as follows:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree