Donna D. Ignatavicius

Assessment of the Gastrointestinal System

Learning Outcomes

Safe and Effective Care Environment

Health Promotion and Maintenance

Psychosocial Integrity

Physiological Integrity

6 Briefly review the anatomy and physiology of the GI system.

7 Describe GI system changes associated with aging.

8 Perform a GI history using selected Gordon’s Functional Health Patterns.

9 Perform focused physical assessment for patients with suspected or actual GI health problems.

10 Explain and interpret common laboratory tests for a patient with a GI health problem.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Iggy/

Animation: Digestion

Animation: Rectal Examination

Answer Key for NCLEX Examination Challenges and Decision-Making Challenges

Audio Glossary

Key Points

Review Questions for the NCLEX® Examination

Video Clip: Abdomen, Bowel Sounds

Video Clip: Palpation of Abdomen

Video Clip: Percussion, Abdomen

Video Clip: Percussion, Liver, Spleen

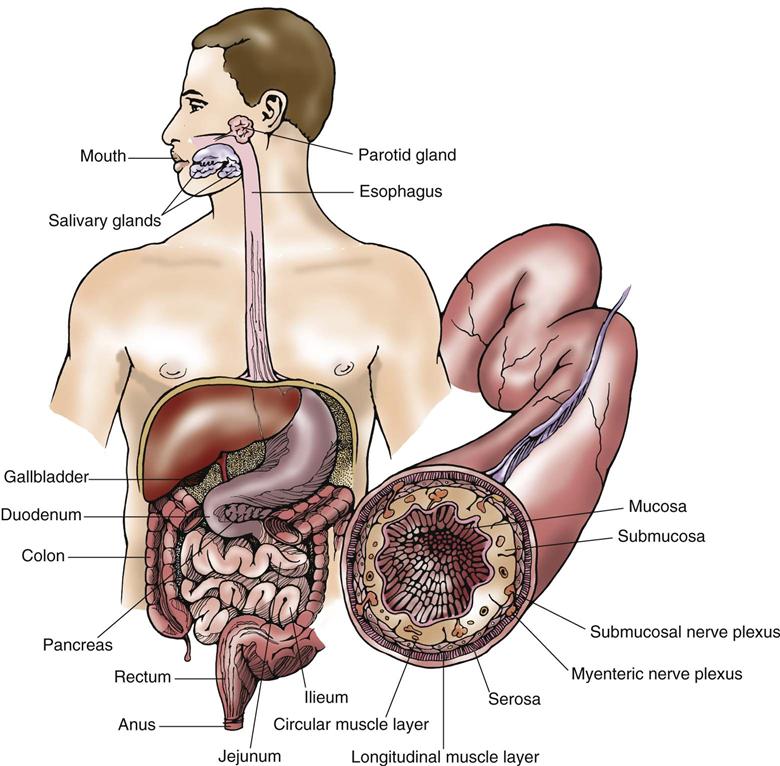

The GI system includes the GI tract (alimentary canal), consisting of the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small and large intestines, and rectum. The salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas secrete substances into this tract to form the GI system (Fig. 55-1). The main function of the GI tract, with the aid of organs such as the pancreas and the liver, is the digestion of food to meet the body’s nutritional needs and the elimination of waste resulting from digestion. Adequate nutrition is required for proper functioning of the body’s organs and other cells (see the Concept Overview). The GI tract is susceptible to many health problems, including structural or mechanical alterations, impaired motility, infection, and cancer.

Anatomy and Physiology Review

Overview of the Gastrointestinal System

Structure

The GI tract is a hollow muscular tube surrounded by four tissue layers. The lumen, or inner wall, of the GI tract consists of four layers: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa. The mucosa, the innermost layer, includes a thin layer of smooth muscle and specialized exocrine gland cells. It is surrounded by the submucosa, which is made up of connective tissue. The submucosa layer is surrounded by the muscularis. The muscularis is composed of both circular and longitudinal smooth muscles, which work to keep contents moving through the tract. The outermost layer, the serosa, is composed of connective tissue. Although the GI tract is continuous from the mouth to the anus, it is divided into specialized regions. The mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines each perform a specific function. In addition, the secretions of the salivary, gastric, and intestinal glands; liver; and pancreas empty into the GI tract to aid digestion.

Function

The functions of the GI tract include secretion, digestion, absorption, motility, and elimination. Food and fluids are ingested, swallowed, and propelled along the lumen of the GI tract to the anus for elimination. The smooth muscles contract to move food from the mouth to the anus. Before food can be absorbed, it must be broken down to a liquid, called chyme. Digestion is the mechanical and chemical process in which complex foodstuffs are broken down into simpler forms that can be used by the body. During digestion, the stomach secretes hydrochloric acid, the liver secretes bile, and digestive enzymes are released from accessory organs, aiding in food breakdown. After the digestive process is complete, absorption takes place. Absorption is carried out as the nutrients produced by digestion move from the lumen of the GI tract into the body’s circulatory system for uptake by individual cells.

Oral Cavity

The oral cavity (mouth) includes the buccal mucosa, lips, tongue, hard palate, soft palate, teeth, and salivary glands. The buccal mucosa is the mucous membrane lining the inside of the mouth. The tongue is involved in speech, taste, and mastication (chewing). Small projections called papillae cover the tongue and provide a roughened surface, permitting the movement of food in the mouth during chewing. The hard palate and the soft palate together form the roof of the mouth.

Adults have 32 permanent teeth: 16 each in upper and lower arches. The different types of teeth function to prepare food for digestion by cutting, tearing, crushing, or grinding the food. Swallowing begins after food is taken into the mouth and chewed. Saliva is secreted in response to the presence of food in the mouth and begins to soften the food. Saliva contains mucin and an enzyme called salivary amylase (also known as ptyalin), which begins the breakdown of carbohydrates.

Esophagus

The esophagus is a muscular canal that extends from the pharynx (throat) to the stomach and passes through the center of the diaphragm. Its primary function is to move food and fluids from the pharynx to the stomach. At the upper end of the esophagus is a sphincter referred to as the upper esophageal sphincter (UES). When at rest, the UES is closed to prevent air into the esophagus during respiration. The portion of the esophagus just above the gastroesophageal (GE) junction is referred to as the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). When at rest, the LES is normally closed to prevent reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. If the LES does not work properly, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can develop (see Chapter 57).

Stomach

The stomach is located in the midline and left upper quadrant (LUQ) of the abdomen and has four anatomic regions. The cardia is the narrow portion of the stomach that is below the gastroesophageal (GE) junction. The fundus is the area nearest to the cardia. The main area of the stomach is referred to as the body or corpus. The antrum (pylorus) is the distal (lower) portion of the stomach and is separated from the duodenum by the pyloric sphincter. Both ends of the stomach are guarded by sphincters (cardiac and pyloric), which aid in the transport of food through the GI tract and prevent backflow.

Smooth muscle cells that line the stomach are responsible for gastric motility. The stomach is also richly innervated with intrinsic and extrinsic nerves. Parietal cells lining the wall of the stomach secrete hydrochloric acid, whereas chief cells secrete pepsinogen (a precursor to pepsin, a digestive enzyme). Parietal cells also produce intrinsic factor, a substance that aids in the absorption of vitamin B12. Absence of the intrinsic factor causes pernicious anemia.

After ingestion of food, the stomach functions as a food reservoir where the digestive process begins, using mechanical movements and chemical secretions. The stomach mixes or churns the food, breaking apart the large food molecules and mixing them with gastric secretions to form chyme, which then empties into the duodenum. The intestinal phase begins as the chyme passes from the stomach into the duodenum, causing distention. It is assisted by secretin, a hormone that inhibits further acid production and decreases gastric motility.

Pancreas

The pancreas is a fish-shaped gland that lies behind the stomach and extends horizontally from the duodenal C-loop to the spleen. The pancreas is divided into portions known as the head, the body, and the tail (Fig. 55-2).

Two major cellular bodies (exocrine and endocrine) within the pancreas have separate functions. The exocrine part is about 80% of the organ and consists of cells that secrete enzymes needed for digestion of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins (trypsin, chymotrypsin, amylase, and lipase). The endocrine part of the pancreas is made up of the islets of Langerhans, with alpha cells producing glucagon and beta cells producing insulin. These hormones produced are essential in the regulation of metabolism. Chapter 67 describes the endocrine function of the pancreas in detail.

Liver and Gallbladder

The liver is the largest organ in the body (other than skin) and is located mainly in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) of the abdomen. The right and left hepatic ducts transport bile from the liver. It receives its blood supply from the hepatic artery and portal vein, resulting in about 1500 mL of blood flow through the liver every minute.

The liver performs more than 400 functions in three major categories: storage, protection, and metabolism. It stores many minerals and vitamins, such as iron, magnesium, and the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.

The protective function of the liver involves phagocytic Kupffer cells, which are part of the body’s reticuloendothelial system. They engulf harmful bacteria and anemic red blood cells. The liver also detoxifies potentially harmful compounds (e.g., drugs, chemicals, alcohol). Therefore the risk for drug toxicity increases with aging because of decreased liver function.

The liver functions in the metabolism of proteins considered vital for human survival. It breaks down amino acids to remove ammonia, which is then converted to urea and is excreted via the kidneys. In addition, it synthesizes several plasma proteins, including albumin, prothrombin, and fibrinogen. The liver’s role in carbohydrate metabolism involves storing and releasing glycogen as the body’s energy requirements change. The organ also synthesizes, breaks down, and temporarily stores fatty acids and triglycerides.

The liver forms and continually secretes bile, which is essential for the breakdown of fat. The secretion of bile increases in response to gastrin, secretin, and cholecystokinin. Bile is secreted into small ducts that empty into the common bile duct and into the duodenum at the sphincter of Oddi. However, if the sphincter is closed, the bile goes to the gallbladder for storage.

The gallbladder is a pear-shaped, bulbous sac that is located underneath the liver. It is drained by the cystic duct, which joins with the hepatic duct from the liver to form the common bile duct (CBD). The gallbladder collects, concentrates, and stores the bile that has come from the liver. It releases the bile into the duodenum via the CBD when fat is present.

Small Intestine

The small intestine is the longest and most convoluted portion of the digestive tract, measuring 16 to 19 feet (5 to 6 m) in length in an adult. It is composed of three different regions: duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The duodenum is the first 12 inches (30 cm) of the small intestine and is attached to the distal end of the pylorus. The common bile duct and pancreatic duct join to form the ampulla of Vater, emptying into the duodenum at the duodenal papilla. This papillary opening is surrounded by muscle known as the sphincter of Oddi. The 8-foot (2.5-m) portion of the small intestine that follows the sphincter of Oddi is the jejunum. The last 8 to 12 feet (2.5 to 4 m) of the small intestine is called the ileum. The ileocecal valve separates the entrance of the ileum from the cecum of the large intestine.

The inner surface of the small intestine has a velvety appearance because of numerous mucous membrane fingerlike projections. These projections are called intestinal villi. In addition to the intestinal villi, the small intestine has circular folds of mucosa and submucosa, which increase the surface area for digestion and absorption.

The small intestine has three main functions: movement (mixing and peristalsis), digestion, and absorption. Because the intestinal villi increase the surface area of the small intestine, it is the major organ of absorption of the digestive system. The small intestine mixes and transports the chyme to mix with many digestive enzymes. It takes an average of 3 to 10 hours for the contents to be passed by peristalsis through the small intestine. Intestinal enzymes aid in the digestion of proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids.

Large Intestine

The large intestine extends about 5 to 6 feet in length from the ileocecal valve to the anus and is lined with columnar epithelium that has absorptive and mucous cells. It begins with the cecum, a dilated, pouchlike structure that is inferior to the ileocecal opening. At the base of the cecum is the vermiform appendix, which has no known digestive function. The large intestine then extends upward from the cecum as the colon. The colon consists of four divisions: ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon. The sigmoid colon empties into the rectum.

Following the sigmoid colon, the large intestine bends downward to form the rectum. The last 1 to  inches (3 to 4 cm) of the large intestine is called the anal canal, which opens to the exterior of the body through the anus. Sphincter muscles surround the anal canal.

inches (3 to 4 cm) of the large intestine is called the anal canal, which opens to the exterior of the body through the anus. Sphincter muscles surround the anal canal.

The large intestine’s functions are movement, absorption, and elimination. Movement in the large intestine consists mainly of segmental contractions, like those in the small intestine, to allow enough time for the absorption of water and electrolytes. In addition, peristaltic contractions are triggered by colonic distention to move the contents toward the rectum, where the material is stored until the urge to defecate occurs. Absorption of water and some electrolytes occurs in the large intestine to reduce the fluid volume of the chyme. This process creates a more solid material, the feces, for elimination.

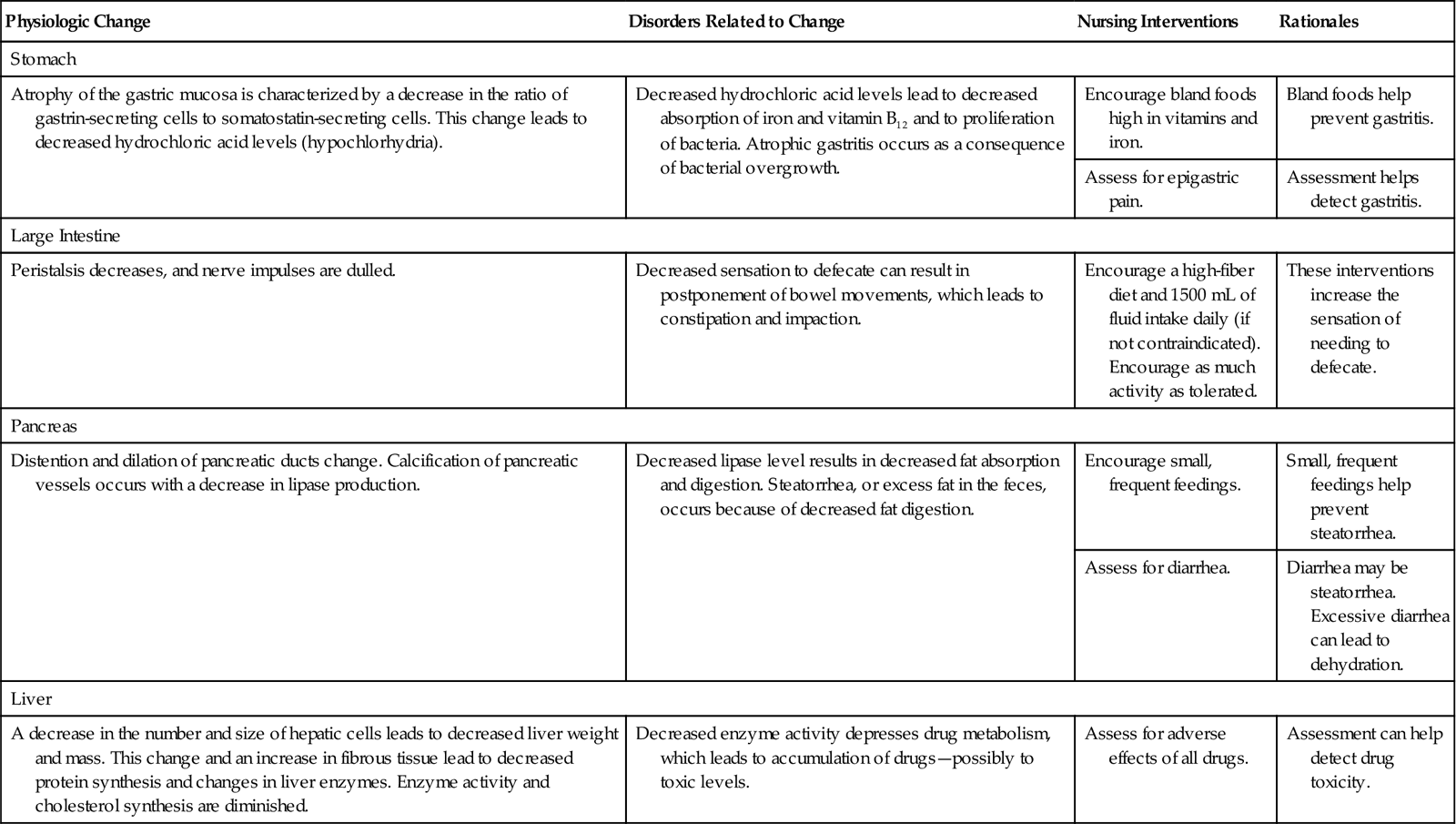

Gastrointestinal Changes Associated with Aging

Physiologic changes occur as people age, especially ages 65 years and older. Changes in digestion and elimination that can affect nutrition are common. For example, decreased gastric hydrochloric acid (HCl) can lead to decreased absorption of essential minerals like iron. Chart 55-1 lists common GI changes and nursing implications when caring for older adults.

Assessment Methods

Patient History

The purpose of the health history is to determine the events related to the current health problem. One tool for assessing GI function is the nutritional-metabolic pattern and the elimination pattern assessment found in Chart 55-2. Focus questions about changes in appetite, weight, and stool. Determine the patient’s pain experience.

Collect data about the patient’s age, gender, and culture. This information can be helpful in assessing who is likely to have particular GI system disorders. For instance, older adults are more at risk for stomach cancer than are younger adults. Younger adults are more at risk for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The exact reasons for these differences continue to be studied.

Question the patient about previous GI disorders or abdominal surgeries. Ask about prescription medications being taken, including how much, when the drugs are taken, and why they have been prescribed. Inquire if the patient takes over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, herbs, and/or supplements. In particular, ask whether aspirin, NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen), laxatives, herbal preparations, or enemas are routinely taken. Large amounts of aspirin or NSAIDs can predispose the patient to peptic ulcer disease and GI bleeding. Long-term use of laxatives or enemas can cause dependence and result in constipation and electrolyte imbalance. Some herbal preparations, especially ayurvedic herbs, can affect appetite, absorption, and elimination. Determine if the patient smokes or has ever smoked cigarettes, cigars, or pipes. Smoking is a major risk factor for most GI cancers. Chewing tobacco is a major cause of oral cancer.

Finally, investigate the patient’s travel history. Ask whether he or she has traveled outside of the country recently. This information may provide clues about the cause of symptoms like diarrhea.

Nutrition History

A nutrition history is important when assessing GI system function. Many conditions manifest themselves as a result of alterations in intake and absorption of nutrients. The purpose of a nutritional assessment is to gather information about how well the patient’s nutritional needs are being met. Inquire about any special diet and whether there are any known food allergies. Ask the patient to describe the usual foods that are eaten daily and the times that meals are taken.

Health problems can also affect nutritional intake, so explore any changes that have occurred in eating habits as a result of illness. Anorexia (loss of appetite for food) can occur with GI disease. Assess changes in taste and any difficulty or pain with swallowing (dysphagia) that could be associated with esophageal disorders. Also ask if abdominal pain or discomfort occurs with eating and whether the patient has experienced any nausea, vomiting, or dyspepsia (indigestion or heartburn). Unknown food allergies often cause these symptoms. Inquire about any unintentional weight loss, because some cancers of the GI tract may present in this manner. Assess for alcohol and caffeine consumption, because both substances are associated with many GI disorders, such as gastritis and peptic ulcer disease.

The patient’s socioeconomic status may have a profound impact on his or her nutritional status. For example, people who have limited budgets, such as some older adults or the unemployed, may not be able to purchase foods required for a balanced diet. In addition, they may substitute less expensive and perhaps less effective OTC medications or herbs for prescription drugs. Necessary medical care may be delayed, and patients may not seek health care until conditions are well advanced.

Family History and Genetic Risk

Ask about a family history of GI disorders. Some GI health problems have a genetic predisposition. For example, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an inherited autosomal dominant disorder that predisposes the patient to colon cancer (McCance et al., 2010). Specific genetic risks are discussed with the GI problems in later chapters.

Current Health Problems

Because GI clinical manifestations are often vague and difficult for the patient to describe, it is important to obtain a chronologic account of the current problem, symptoms, and any treatments taken. Furthermore, ask about the location, quality, quantity, timing (onset, duration), and factors that may aggravate or alleviate each symptom (see Chart 55-2).

For example, a change in bowel habits is a common assessment finding. Obtain this information from the patient:

• Color and consistency of the feces

• Occurrence of diarrhea or constipation

• Effective action taken to relieve diarrhea or constipation

• Presence of frank blood or tarry stools

An unintentional weight gain or loss is another symptom that needs further investigation. Assess the patient’s:

Pain is a common concern of patients with GI tract disorders. The mnemonic PQRST may be helpful in organizing the current problem assessment (Jarvis, 2012):

Q: Quality or quantity. How does it look, feel, or sound? How intense/severe is it?

R: Region or radiation. Where is it? Does it spread anywhere?

Abdominal pain is often vague and difficult to evaluate. Ask the patient to describe the type of pain, such as burning, gnawing, or stabbing. The location of the pain can be determined by asking him or her to point to the involved site. Ask about the relationship of food intake to the onset or worsening of pain. For example, a high-fat meal may cause gallbladder pain.

Changes in the skin may result from several GI tract disorders, such as liver and biliary system obstruction. Ask about whether these clinical manifestations have occurred, or assess whether they are present:

Physical Assessment

Physical assessment involves a comprehensive examination of the patient’s nutritional status, mouth, and abdomen. Nutritional assessment is discussed in detail in Chapter 63. Oral assessment is described in Chapter 56.

In preparation for examination of the abdomen, ask the patient to empty his or her bladder and then to lie in a supine position with knees bent, keeping the arms at the sides to prevent tensing of the abdominal muscles.

The abdominal examination usually begins at the patient’s right side and proceeds in a systematic fashion (Fig. 55-3):

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree